The Status Familiae in Roman Law

The family status, familial status, or status familiae, is the legal situation of a free individual and Roman citizen, in relation to his agnatic family. This... (leer más)

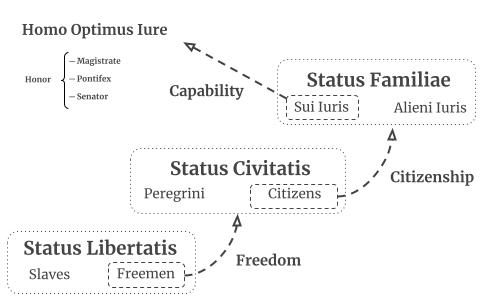

People in Ancient Rome were classified according to their standing to enjoy and exercise their rights within the Roman society. This classification determined their legal, social and political position in the city, and it is called 'civil status'.

This civil status sort people into at least three (3) groups, each one with two options: (a) those who possessed or not their freedom, (b) those who possessed or not Roman citizenship, and (c ) those who possessed or not the paternal power inside their family.

Each of these situations were called status, and represented the possession─or not─of a legal attribute, such as freedom, Roman citizenship, and familial authority. However, they were not the attribute itself, but the legal effects of their standing.

Romans, in order to sort which regulation they would apply to a specific case, they examined first the civil status of the people involved in that case, since normative bodies were different, wherever for a slave, for a foreigner, or for a senator. Because of Roman legal system.

Civil Status: Civil standing of a person to enjoy and exercise their rights.

This definition, is based on two great moments of compilation of Roman law, first, from the Justinian compilations that define the relationship between citizens and the city, as can be seen in the chapter of the Digest about general aspects of law:

Cum igitur hominum causa omne ius constitutum sit, primo de personarum statu ac post de ceteris, ordinem edicti perpetui secuti et his proximos atque coniunctos applicantes titulos ut res patitur, dicemus.

(Therefore, all rights are caused by the agreement of men, first with respect to the legal regime of persons, and then to the rest, followed by the ordering of perpetual edicts, and we would say later, as regards the regime of titles and things)

Hermogenian [1]

(Translation from the author*)

And a second moment, during 16th and 17th centuries, with the Renaissance glossers of Roman law, who did an interpretive work of the sources at their disposal, in order to, besides compiling, to systematize the way in which Romans understood legal relationships, and applied their legal system.

From these systematizations emerged the─now─evident division between the state of family and that of citizenship.

[1]: Hermogenian | Digest: Vol. 1, Tit. 5, Sec. 2.

HSD

In order to classify the stages of the civil status of people in Roman law, two (2) characteristics must be taken into account: (a) they were progressive, that is, one cannot be moved from one status up to another without also maintaining the previous status; and (b) they were staggered, that is to say, the next status represents an improvement in the legal conditions of whoever is located there.

These status were:

People who had the three states, that is, they were freemen, Roman citizens and heads of their common family law would be called homo optimus iure.

However, there were other factors that also influenced when placing a person in their civil status, such as sex, age or infamy, which although they were not a stage in the civil status, limited the ability to enjoy or exercise rights.

In Roman law, the status libertatis (status of being freeman) sorted people according to the ownership of their body and life. Freemen being those who had no master but themselves, and slaves those who were not masters of themselves.

For this reason, the status of freemen would be the basis on which the legal personality of individuals and the recognition of any other right are built.

In general, the status of freemen is associated with the legal attribute of freedom, since only a person who owns himself can act of his own free will, being the slaves constrained to act as ordered by their owner. However, the terms are not equivalent, hence some states of quasi-slavery present in Roman law, such as the children given in mancipium.

For Romans, freedom, which was the ability to act at will, being the basic distinction between a thing─totally lacking will─and a person. For this reason slaves were legally considered things, although they were not it naturally.

Like the rest of the civil status of person, the status libertatis would have two legal options: (a) that of freemen and (b) that of slavery.

Freemen were those one with full autonomy to act physically, without the consent of anyone and according to their abilities. This distinction of "physically" is important, because legally autonomy was configured only with the status of sui iuris.

Free people could be of three categories,

Slaves were not really considered people, but things, personal property of their bosses; they were totally without rights, and whose master could do whatever they wanted with them.

In Roman law, the status civitatis (status of being citizen) was the legal status of belonging to the populus romanus or Roman civil society. It determined the legal remedies that a person have in relation to the city of Rome, and classifies free people into Roman citizens and foreigners.

Roman citizens were those who have a legal, social and moral bond with Rome, manifested in the duty to serve in Roman army, and in return, with the ownership of quiritary rights, which would be the rights to marry, inherit, trade, vote and become a magistrate.

They were made up of all those who were not Roman citizens, but were able to get in Rome, therefore they did not enjoy the same advantages as citizens. They were in general:

In Roman law, the status familiae (status of being headman) is the status of civil authority that a person possesses within their agnatic family and the Roman society. It consisted in the standing of individuals within the Roman socio-family environment.

It had two categories, (a) sui iuris or (b) alieni iuris, depending on whether it was subject to the paternal power of anyone or not.

Constituted of people who were the heads of their own family law and therefore were not subject to the paternal power of anyone. However, this did not imply per se the full exercise of their rights, since some sui iuris were in situations of legal protection, very similar to the status of an alieni iuris.

Roman citizens who were subject to the family law of another, or paternal power, were called alieni iuris. They had the same privileges of a Roman citizen, but reduced, since they depended on the mediation of the pater familias.

An example of this is the Roman civil marriage, which required the express consent of the pater familias to be exercised, even if the rights was in head of the filius.

The Capitis Deminutio or decrease of capacity is the Latin expression that designates the loss or diminution of the legal capacity of a person in Ancient Rome. This could be total or partial.

The Capitis Deminutio was divided into Maxima Deminutio, Minor Deminutio and Minimum Deminutio.

In Roman law, infamy is a civil sanction that degrades the legal capacity of a person.

Infamy altered the civil status, but it did so as an extraordinary condition, in cases where the citizen had had a behavior that could be considered socially reprehensible. As a consequence, they could not vote in elections, attend religious rites, occupy magistrates and even marry or trade.

AcademiaLab© Actualizado 2024

This post is an official translation from the original work made by the author, we hope you liked it. If you have any question in which we can help you, or a subject that you want we research over and post it on our website, please write to us and we will respond as soon as possible.

When you are using this content for your articles, essays and bibliographies, remember to cite it as follows:

Anavitarte, E. J. (2015, December). The Civil Status in Roman Law. Academia Lab. https://academia-lab.com/2015/12/15/the-civil-status-in-roman-law/

The family status, familial status, or status familiae, is the legal situation of a free individual and Roman citizen, in relation to his agnatic family. This... (leer más)

For Romans, the contubernium or contubernium marriage frames in a generic way all kind of sexual relationships with slaves, whether between themselves, or... (leer más)

The usufruct is a type of personal easement, constituted on a thing ─generally immovable─, which endows the usufructuary with the real rights of use and... (leer más)