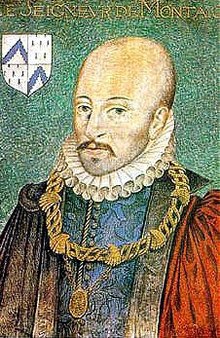

Michel de Montaigne

Michel Eyquem de Montaigne [miʃɛl ekɛm də mõ'tɛɲ ] (Montaigne Castle, Saint-Michel-de-Montaigne, February 28, 1533-Montaigne Castle, Saint-Michel-de-Montaigne, September 13, 1592) was a French philosopher, writer, humanist and moralist of the Renaissance, author of the Essays and creator of the literary genre known in the Modern Age as essay. It has been described as the most classic of the moderns and the most modern of the classics. His work was written in the tower of his own castle between 1572 and 1592 under the question "What do I know?" ? & # 3. 4;.

Biography

Montaigne was born near Bordeaux in a château owned by his paternal family, on February 28, 1533. His maternal family, of Spanish Jewish descent, came from Aragonese Jewish converts, the López de Villanueva, documented in the Jewish quarter of Calatayud; some of them were persecuted by the Spanish Inquisition, including Raimundo López who, in addition, was burned at the stake. On his maternal side, then, he was a second cousin of the humanist Martín Antonio del Río, whom he was able to meet personally between 1584 and 1585 Michel's paternal family (the Eyquems) enjoyed a good social and economic position and he studied at the prestigious Collège de Guyenne in Bordeaux. Montaigne is the brother of Jeanne de Montaigne, married to Richard de Lestonnac and therefore the uncle of Saint Jeanne Lestonnac.

Childhood

He received from his father, Pierre Eyquem, mayor of Bordeaux, an education that was both liberal and humanist: as a newborn he was sent to live with the peasants of one of the villages he owned so that he would experience poverty. A few years after his life, back in his castle, they always woke him up with music, and in order for him to learn Latin, his father hired a German tutor who did not speak French and forbade the employees to address the child in French.; thus, he had no contact with this language during his first eight years of life. Latin was his mother tongue; then he was taught Greek and after he fully mastered it he began to hear French.

I work as a magistrate

Then he was sent to the Bordeaux school and there he completed the twelve school years in only seven years. He later graduated with a law degree from the University. His family contacts earned him the position of magistrate of the city and in that position he met a colleague who would be his great friend and correspondent, Étienne de La Boétie, author of a Discourse on voluntary servitude that Montaigne very much appreciated; his early death left him devastated; this kind of friendship, he wrote, was of the kind found 'only once in three centuries [...] Our souls marched so close that I did not know if it was his or mine, although I certainly did. I have felt more comfortable trusting him than myself'. The next twelve years (1554-66) were spent in court.

Humanist and Skeptic: the Essays

Admirer of Lucretius, Virgil, Seneca, Plutarch and Socrates, he was a humanist who took man, and himself in particular, as an object of study in his main work, the Essays (Essais) started in 1571 at the age of 38, when he retired to his castle. He wrote, "[I] want to be seen in my simple, natural, and ordinary form, without restraint or artifice, for I am the subject of my book." Montaigne's project was to show himself without masks, to go beyond artifice to reveal his most intimate self in his essential nakedness. Doubtful of everything, he only firmly believed in truth and freedom.

He was a sharp critic of the culture, science, and religion of his day, to the point where he came to regard the very idea of certainty as unnecessary. His influence on French, Western, and world literature was colossal, as the creator of the genre known as the essay.

Wars of Religion

During the time of the religious wars, Montaigne, himself a Catholic but with two Protestant brothers, tried to be a moderator and compromise with the two warring sides. He was respected as such by the Catholic Henry III and the Protestant Henry IV.

Since 1578 he began to suffer from the same stone disease that had ended up killing his father, he decided to travel to the main spas in Europe to take their waters, also taking advantage of this to distract himself and educate himself / se distractire et s& #39;instruire. From 1580 to 1581, he traveled through France, Germany, Austria, Switzerland, and Italy, keeping a detailed journal where he described varied episodes and the differences between the regions he passed through. However, this writing was only published in 1774, under the title Travel Journal. He first went to Paris, where he presented the Essais to Henry III of France. He stayed for a long time in Plombières and Baden, and then went to Munich. He then went to Italy through Tyrol, settled in Rome (1581) and then traveled to Lucca, where in September of that same year he learned that he had been elected mayor of Bordeaux.

His father Pierre Eyquem had already been mayor of this town, which Michel governed until 1585. The first two years were easy, but everything got complicated when he was re-elected in 1583 and was forced to deal with the VIII War of Religion and moderate tensions between Catholics and Protestants. Which he achieved by showing great diplomatic skills, as he reconciled Henry III of Navarre with Marshal Jacques de Goyon, Lord of Matignon and Lesparre, Count of Thorigny, Prince of Mortagne sur Gironde and Governor of Guyenne. He also managed, together with Matignon, to prevent a League attack on Bordeaux in 1585. Towards the end of his term, in the summer of this last year, the plague besieged this city, and he decided not to preside, as was traditional, the act of election of his successor and return to his possessions with his own.

The Court refused

Henry IV, with whom he always maintained a friendly relationship, invited him to the Court after winning the battle of Coutras in October 1587, once again reinstated as King of France. But Montaigne was robbed and robbed on the way to Paris; he also stayed a few hours in the Bastille while the Day of the barricades took place. The king offered him the position of royal adviser but, remembering Plato's sad role at the court of the tyrant Dionysius of Syracuse, he declined such a generous proposal: «I have never received any generosity from kings, which I have neither asked for nor deserved, nor have I received any payment for the steps I have taken in his service. [...] I am, sire, as rich as I imagine».

In that same year he met his great admirer, Mademoiselle or M.elle Marie Le Jars de Gournay, who will be his fille d' alliance or "elective daughter" and she brought to light the so-called & # 34; posthumous edition & # 34; from the Essais in 1595, with Montaigne's post-1588 additions and corrections; this edition was long considered the most authoritative, although modern publishers today prefer the one that, with Montaigne's own handwritten notes, is kept in the Bordeaux Municipal Library.

"What do I know?"

Montaigne continued to revise and extend his Essays (the fifth edition, from 1588) with a third book until his death on September 13, 1592 in the castle that bears his name, in whose ceiling beams had his favorite quotes engraved. The motto, nickname or emblem of his tower was «Que sais-je?» («What do I know?» or «What do I know?»), and he had it coined a medal with a scale whose two plates were balanced.

His posterity was divided in the judgment that his work deserved, and thus to the severe opinion of Blaise Pascal that it was "a foolish project that Montaigne had to paint himself" / le sot project que Montaigne a eu de se peindre answered the more moderate Voltaire that it was charming «the project that Montaigne had to paint himself naively, as he did. Well, he painted human nature »/ le charmant project que Montaigne a eu de se peindre naïvement, comme il a fait. Car il a peint la nature humaine. Voltaire, in fact, paraphrased a thought of Montaigne himself: "Each man bears the entire form of the human condition." However, Pascal's criticism must be borne in mind he tells knowing that the project of painting himself to instruct the reader was not so original; Saint Augustine of Hippo had already declared it in his Confessions: «I have no other purpose than to paint myself [...] It is not my actions that I describe, but me: it is my essence".

Statue in the Latin Quarter of Paris

His statue, erected in the 1930s, and located on Place Paul Painlevé in the central Latin Quarter of Paris, serves as a lucky charm for students at La Sorbonne, which stands right in front, and who, before exams, touch the right foot of the statue.

His work

Montaigne wrote with a festive and frank pen, mixing one thought with another, "by leaps and bounds." His text is continually embellished with quotes from Greco-Latin classics, for which he excuses himself by noting the uselessness of "going back to say worse what another has said better first." Obsessed with avoiding pedantry, he sometimes omits the reference to the author who inspires his thoughts or whom he quotes and who, in any case, is known in his time. Later annotators supplied this trifle.

He considers that his purpose is «to describe man and myself in particular [...] and there is as much difference between me and myself as between me and another». He judges that variability and inconstancy are two of its essential characteristics. "I have never seen such a great monster or miracle as myself." He refers to her poor memory and her ability to slowly delve into matters spiraling around them so as not to become emotionally involved, her distaste for men who pursue celebrity, and her attempts to detach herself from the things of the world and prepare for death. His famous nickname or emblem of him, Que sais-je?, which can be translated as What do I know? or I don't know! It clearly reflects that detachment and that desire to internalize the rich inner world of him and is the starting point of all his philosophical development.

Montaigne shows his aversion for violence and for the fratricidal conflicts between Catholics and Protestants (but also between Guelphs and Ghibellines) whose medieval conflict became more acute during his time. For Montaigne, it is necessary to avoid reducing the complexity of the binary opposition and the obligation to choose sides, favoring skeptical withdrawal as a response to fanaticism. In 1942, Stefan Zweig said of him: «Despite his infallible lucidity, despite the pity that overwhelmed him to the bottom of his soul, he must have witnessed this despicable fall of humanism into bestiality, some of those sporadic attacks of madness that sometimes constitutes the human. [...] That is the real tragedy of Montaigne's life».

While some humanists believed they had found the Garden of Eden, Montaigne lamented the conquest of the New World because of the suffering it brought to those who were subjugated by it through slavery. He thus spoke of "vile victories." He was more horrified by the torture that his peers inflicted on some living beings than by the cannibalism of those same Amerindians whom he called savages.

As modern as many of the men of his time (Erasmus, Juan Luis Vives, Tomás Moro, Guillaume Budé...), Montaigne professed cultural relativism, recognizing that the laws, morals and religions of different cultures, - although often diverse and remote in their principles - all had some foundation. "Not capriciously changing a received law" constitutes one of the most incisive chapters of the Essays. Above all, Montaigne is a great supporter and defender of Humanism. If he believes in God, he refuses all speculation about his nature and, since the self manifests itself in its contradictions and variations, he thinks that it must be stripped of misleading beliefs and prejudices.

His writings are characterized by a pessimism rare in the Renaissance era. Citing the case of Martin Guerre, he thinks that humanity cannot expect certainties and rejects absolute and general propositions. In the long essay Apology of Raymond Sebond (Raimundo Sabunde), chapter 12, second book, he states that we cannot believe our reasoning because thoughts appear to us without an act of will; we do not control them, we have no reason to feel superior to animals. Our eyes only perceive through our knowledge:

If you ask the Philosophy of what matter is heaven and sun, what will she answer you, but of iron or, with Anaxagoras, of stone or such scam according to our custom?[... ]

May one day please Nature open your breast and make us see the means and guidance of your movements, and let us set our eyes there! Oh, God! What a detour, how empty we would find in our poor knowledge!Michel de Montaigne, Tests

He judges marriage as a necessity to allow the education of children, but he thinks that romantic love is an attack on the freedom of the individual: «Marriage is a cage: the birds outside are desperate to enter, but those inside They are desperate to get out."

In short, it proposes in educational matters the entrance to knowledge through concrete examples and experiences rather than through abstract knowledge accepted without any criticism. He refuses, however, to become a spiritual guide himself, a teacher of thought: he does not have a philosophy to defend above all others, considering that his is only a company in search of identity.

Freedom of thought is not proposed as a model, since it simply offers men the possibility of making the power to think emerge in them and of assuming this freedom: «The one that teaches men to die as one learns to live ». And this freedom earned him the condemnation of the Index librorum prohibitorum of the Holy Office in 1676 at the request of Bossuet.

The Essays/Essais conclude with an epicurean invitation to live joyfully: «There is no perfection so absolute and so to speak divine as knowing how to get out of being. We look for other ways of being because we don't understand the use of ours, and we go outside because we don't know what the weather is like outside. In the same way, it is useless to climb on stilts to walk, because even then we will have to walk with our legs. Even on the highest throne in the world we are only sitting on our asses."

Essay Editions

Montaigne gave the Bordeaux press in 1580 the first two books of his essays. For a new edition, Montaigne lavishly annotated a copy of his works from 1588, known as the Bordeaux Copy, with hundreds of new comments, additions and qualifications, but death surprised him before he could hand it over to the publisher.. His admirer, Marie de Gournay, took the text and edited it for the version that was published in 1595. All subsequent editions and translations were made of the Bordeaux Copy, dismissing De Gournay's edition.

Translations of essays

The Essays were known very soon in Baroque Spain, thanks to the partial translations of the Discalced Carmelite Diego Cisneros (Experiences and various speeches of Mr. de la Montaña), perhaps commissioned by Quevedo, and the uncle of the Count-Duke of Olivares, the ambassador in France Baltasar de Zúñiga, but none of these manuscripts reached the printer. The Ejemplar de Bordeos was translated for the first time by Constantino Román Salamero in 1898. The best Spanish translations of the century were also made from it XX, that of María Dolores Picazo or that of Marie-José Lemarchand.

In 1947, a summarized edition of the Essays was published, illustrated by Salvador Dalí and whose texts were also chosen or supervised by the famous painter. This edition, in English, was intended for the US market.

From the XX century are the translations by Juan G. de Luaces (Mexico: UNAM, 1959), the aforementioned by Constantino Román y Salamero revised by Ricardo Sáenz Hayes (Buenos Aires: Aguilar, 1962, 2 vols.) and that of Enrique Azcoaga (Madrid: Rialp, 1971).

The most recent work by Jordi Bayod (2007), on the other hand, is based on the critical edition of Marie de Gournay's in 1595 by La Pléiade, since critics have come to the conclusion that Bordeaux copy was a mere working copy and de Gournay edited a later manuscript.

The latest modern translations that can be cited are:

- Montaigne, Michel of (1994). Tests I, II and III. Editing and translation of Maria Dolores Picazo and Almudena Montojo. Barcelona: Altaya Editions. ISBN 978-84-376-0539-5.

- Montaigne, Michel de (1998). Tests I, II and III. Editing and translation of Maria Dolores Picazo and Almudena Montojo. Madrid: Chair. ISBN 978-84-376-0539-5.

- Montaigne, Miguel de (2005). Tests I. Introduction, translation and notes by Marie-José Lemarchand. Madrid: Gredos. ISBN 978-84-96834-17-0.

- Montaigne, Michel of (2007). The essays (according to the 1595 edition of Marie de Gournay). Prologue of Antoine Compagnon. Edition and translation of J. Bayod Brau. Collection Essay 153. 1738 pages. Fifth edition. Barcelona: El Acantilado. ISBN 978-84-96834-17-0.

- Montaigne, Michel de (2013). Complete testing. Bilingual edition. Introduction and notes by Alvaro Muñoz Robledano. Almudena Montojo translation. Madrid: Chair (Biblioteca Áurea). ISBN 84-37631475.

- Montaigne, Michel de (2014). Tests. First bilingual French-Spanish edition. Translation, notes, introduction and bibliography of Javier Yagüe Bosch. Barcelona: Gutenberg Galaxy/Lector Circle. ISBN 978-84-15472-65-0.

- Montaigne, Michel de (2016). Rehearsals. Diary of the trip to Italy. Correspondence. Editing and translation of Gonzalo Torné. Madrid: Penguin Classics. ISBN 978-84-9105-249-4.

- Montaigne, Michel de (2018). Tests. Translation by Angel López Garrido. La Poveda (Arganda del Rey), Madrid: Editorial Verbum. ISBN 978-84-9074-702-5.

- Montaigne, Michel de (2021). Tests. Second bilingual French-Spanish edition. Editing, translation, notes, introduction and bibliography by Javier Yagüe Bosch. Barcelona: Gutenberg Galaxy. ISBN 978-84-18807-23-7.

Contenido relacionado

Manuel Murguia

Mathurin Regnier

Romain Rolland

Emilio oribe

Mary Wollstonecraft