The Marriage in Roman Law

Marriage or lawful nuptials (iustae nuptiae), is a solemn legal business, through which a man and a woman were united in a relationship with civil and... (leer más)

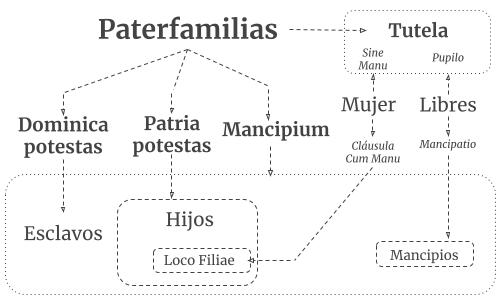

Roman private law was organized around the figure of the paterfamilias, who had to be a Homo Optimus Iure person, what means, he had to be free, citizen and not under the authority of anyone else.

The paterfamilias was the absolute owner of everything that was within his family unit, being able to dispose of it and also directing private religious life, as supreme priest.

This patriarchal figure with such wide powers is a normal evolution of the first forms of Roman tribal organization, where a chief-father directed all the affairs of his tribe-family and precisely this is the reason for the very particular kinship system by agnation, typical of Romans.

When defining the paterfamilias, it must be taken into account that the entire family structure of the Roman world revolves around his person; the woman is always relegated to a background position, inside the domus, and the children are, until the death of the paterfamilias, totally dependent on his authority. Hence the family is the paterfamilias in his own right.

Paterfamilias: Roman citizen who forms and exercises authority over the agnatic family.

[1]

The paterfamilias should always be sui iuris, which endowed them with the legal capacity to form a family, being the family an extension of their own personal right; therefore the iconic Roman family structure, based on the relationships of this sui iuris and his alieni iuris.

The family of the paterfamilias, not only emotionally links him, but also legally belongs to him, hence the great powers that he could exercise over them, such as the sales by mancipatio, or noxal abandonment. All, fallen into disuse at the end of the Low Empire, like the same power of the paterfamilias.

[1]: Paterfamilias | Glossary of Roman law (Spanish).

The paterfamilias was characterized by representing an almost absolute patriarchal authority, it had to be a man, a Roman citizen and sui iuris, and in addition, it exercised both civil and legal power, as well as moral and religious power. So the entire Roman family revolved around the paterfamilias.

In principle (a) every sui iuris citizen had the vocation to become a paterfamilias if they married, so the paterfamilias were always sui iuris, and both terms designate two different aspects of the same reality.

The paterfamilias (b) could only be a man, and (c) his authority was absolute, although with the historical evolution of Roman law and society, the family model based on blood ties and not on authority was consolidated, which that would limit the authority of the Pater.

The paterfamilias had great power over the members of its family, which was manifested in four (4) powers, each one representing the power over a different type of alienated from their family group: power in manus, parental power, mancipium, and magistral power.

These powers were the evolution of the custom throughout the formation of Roman state, but later they would be delimited with the laws and the praetorial edicts.

The mancipium was a Roman legal figure, of customary creation, which implied the authority of a paterfamilias over another free person. This power included the children of the pater, the wife in manu, and the persons given to him by mancipium.

People under the power of mancipium were in a legal situation typical of the alieni iuris, this means, they were free and Roman citizens but everything they acquired became part, through the mancipium, of power and disposition of the paterfamilias. This ended when the status of sui iuris was acquired, or because of manumission.

It was common for the parents of humble families to give their children in mancipium in exchange for a payment, compensation for damage (noxal abandonment) or as a guarantee pledge; for which it was embodied in the law of the XII Tables that, who sold his son more than three times, will lost their parental power.

The most basic power that a paterfamilias would have and that survives until modern legislation was the patria potestas (parental authority). This is represented on the right of the pater by on his legitimate children, or what is the same, their civil agnates.

This power is exclusive to the ius civile, so only Romans could have the parental authority of others, and be subject to it. For Romans, this figure represented one of their most distinctive characteristics, to the point that classical authors such as Gaius, argued that of all the known peoples, only the Gallates would have a similar system.

Unlike the magistral power, which is found in all nations, and which determines the relationships between the master and his slave.

The father could do with his children, almost everything he could do with a slave, he could sell them, punish them─even with death─dispose of them to work, etc. So their biggest difference would not be in their relationship with the authority of the paterfamilias, but in their civil legal situation.

So for example, these filius familias (offspring) could enjoy all the rights of the ius publicum, could vote, or serve in the army; they were considered people, not things, and in addition, they came out of this situation easier, either through the death of their father, or through his repeated sale (emancipation).

During the first part of the history of Ancient Rome, given the patriarchality of Roman family life, women had little relevance in almost all areas of Roman life, this fact was legally represented by custom to add a clause called manus at the time of contracting just nuptials that gave the paterfamilias the parental─civil─authority over the woman, turning her into agnate.

This power was exercised by the paterfamilias of the family group to which the husband of the married cum manu woman belonged, thus, when the husband was the paterfamilias, the woman passed to the position of being legally a daughter, which was called loco filiae. However, if the husband was an alieni iuris, who exercised power over the married cum manu woman would then be the paterfamilias to which her husband was alienated, that is, her father-in-law or the grandfather of her husband.

The power cum manu was a product of custom and was changing as Roman society moderated its social and family practices, which produced an increase in marriages sine manu, to the point that by the time of Emperor Justinian I the Great it was already a anachronistic practice.

The dominica potestas or magistral power constitutes the power that paterfamilias had over slaves, since they were property of the family and therefore over the dominion and disposition of the pater. This power was configured by constituting authority over people, who although legally they were things, still had the vocation of a person from the natural point of view, therefore they could be manumitted (which would not operate with a farm or with a cow).

In principle, the dominica potestas implied the right over the life and death of slaves, and by extension over their work and living conditions. However, with the passage of time, Roman legislation imposed limitations on the exercise to the power of masters, such as the impossibility of killing them without a just cause, or the obligation to sell them if slaves was excessively being abused.

Patresfamilias are legally classified as sui iuris, but not necessarily all sui iuris are patresfamilias, as it may happen that a sui iuris has not yet been married.

So what endows the paterfamilias with his power is both its status as sui iuris, as well as that of a married man, through a Roman civil marriage─iustae nuptiae─.

Because others agnate to him, necessarily depend on the existence of a family, only possible under the iustae nuptiae. Any child born in the absence of a legitimate marriage, simply were cognate of his father sui iuris, and therefore did not give rise to the emergence of parental power on the side of the father, a requirement to call him paterfamilias.

In the event that a legitimate marriage also existed, but between two alieni iuris, the man would not become paterfamilias, since as alieni iuris he could not acquire rights over others, so his children would be agnate from the paterfamilias of their father.

Then, these two conditions had to be present: (a) the paterfamilias was a sui iuris, and (b) he must have been married.

In the event that he lost the status of sui iuris, he immediately lost the effects of parental power and his status as paterfamilias, but he could recover it in case of regaining the condition. In contrast, the same did not happen with divorce, since it continued to be paterfamilias of children of the family he already had, but not of new ones emerged without marriage.

This is due to the way in which capitis deminutio and divorce operates legally. Capitis has retroactive effect─ex tunc─extinguishing all that far arising from their legal status, while divorce has immediate effects─ex nunc─so only solves the new legal situations that arise.

After the death of the paterfamilias, a series of legal consequences began that altered the social roles of their heritage, their social image and their children. First (a) the assets of the paterfamilias entered a post-mortem universal succession, or inheritance, keeping their patrimony united and socially productive.

In addition, two other notorious consequences would derive from his death: on the one hand (b) his family cult began, very important within the Roman religion, and that in many cases turned the deceased into a minor god, as was the case of Quirite or Augustus.

And (c) all of his sons became sui iuris , meaning they could also become paterfamilias, inherit part of his estate, and continue their own lineage. The women, for their part, remained in the hands of their sons or their husbands.

AcademiaLab© Actualizado 2024

This post is an official translation from the original work made by the author, we hope you liked it. If you have any question in which we can help you, or a subject that you want we research over and post it on our website, please write to us and we will respond as soon as possible.

When you are using this content for your articles, essays and bibliographies, remember to cite it as follows:

Anavitarte, E. J. (2016, May). The Paterfamilias in Roman Law. Academia Lab. https://academia-lab.com/2016/05/08/the-paterfamilias-in-roman-law/

Marriage or lawful nuptials (iustae nuptiae), is a solemn legal business, through which a man and a woman were united in a relationship with civil and... (leer más)

The historical periods of Roman law, are the natural division of each of the facets that Roman law had in its development, essential to understand the scope... (leer más)

The classical period of Roman law, are the set of legal manifestations, which occurred between the centuries I until the beginning of III AD, during which... (leer más)