The Patria Potestas in Roman Law

In the Roman law, patria potestas or patria potestad is the institution of civil law that represents the power of paterfamilias over the people and property... (leer más)

The capitis deminutio o capitis diminutio (both right) is the legal phenomenon that represents the decreased ability of a person to have and exercise ownership rights.

This phenomenon occurred when losing attributes that define the civil status of a person in Roman society, such as losing freedom, losing citizenship or losing legal autonomy.

The consequence of capitis deminutio can be variable, but it always implies a decrease in the position of the individual within the regime of the people.

In general, one of the best ways to understand the way in which the Romans organized their civil law is through the capitis deminutio, or decrease in legal capacity, since it allows us to elucidate the true scope of the attributes of the personality, and the hierarchy that the Romans gave to these attributes.

Capitis Deminutio: 1 Decrease in legal capacity.

Capitis Deminutio: 2 Change from a state of the regime of people, to a lower one.

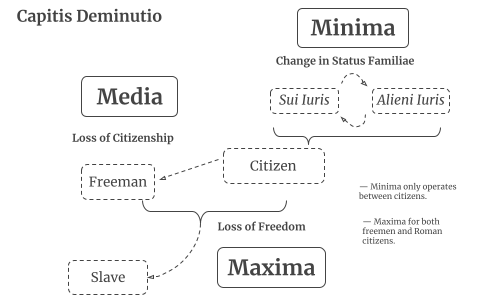

The capitis deminutio, could be maximum, minor, or minimum, but what the Romanists commonly call minor, can be called in a complete sense: capitis deminutio media.

Est autem capitis deminutio prioris status commutatio, eaque tribus modis accidit: nam aut maxima est capitis deminutio aut minor, quam quidam mediam vocant, aut minima.

(The decrease in capacity is nothing other than the change of a better state, which in three ways worsens: thus, either the decrease in capacity is maximum, or less, which some call medium, or minimum)

Justiniano [1]

(Translation from the author*)

[1]: Justinian | Institutes: Lib. 1, Tit. 16, Para. 1.

The Romans distinguished three types of deminutic capitis, one for each element of the caput─legal personality─which were: (a) the maximal deminutic capitis, (b) the lesser deminutic capitis, and (c) the minimal deminutio capitis.

Each of them had the legal effect of depriving the individual's personality of the rights derived from the lost state. For example, the maximum deminutio capitis deprived him of the benefits of freedom, the minor, of the benefits of citizenship, and the minimum of the benefits of the agnatic family.

This classification is very typical of Roman law, and is due to the theoretical construction that the Romans made of the legal personality. For them the person has no inherent existence, but it depends on your personality, caput or status, from which all subjective rights are made.

Given this, the need to regulate legal situations arising from changes in the individual's relationship with society, such as when he was adrogated, or on the contrary, when he was emancipated, made the concept to be consolidated.

It consists of any of the changes that the individual could undergo in his family status, and it operated, whether it was made sui iuris, or alieni iuris, provided that the change implied a degradation of the rights in his head.

Hence, if a child 's family, went from being alieni juris under the custody of his father, whose death makes ipso iure in sui iuris, no mention of minimum deminutio capitis, because not lost the child right some, and instead has been able to gain greater benefits with this change.

But if the same son becomes sui iuris by emancipation, if we speak of a deminutio capitis, because although he gains his full legal autonomy, he loses the rights that he previously had as agnate of his father, for example, his inheritance rights are degraded, to the same as having a cognate.

The same happens, when the alieni iuris change from one power to another, because even if they remain in the same legal status that they had before the change, that of alieni iuris, the mere change deprives them of potential beneficial situations, and they are therefore consider a demerit.

Minima est capitis diminutio, cum et civitas et libertas retinetur, sed status hominis commutatur; quod accidit in his, qui adoptantur, item in his, quae coemptionem faciunt, et in his, qui mancipio dantur quique ex mancipatione manumittuntur

(Capitis deminutio is minimal, when citizenship and freedom are retained, but their status as a person changes; in what falls, by adoption, or also by simulated sale, or also by the emancipation that manumite the mancipio)

Gayo [2]

(Translation from the author*)

[2]: Gayo | Institutions: Lib. 1, Sec. 162.

Although it was the least frequent, an individual could lose only Roman citizenship, without thereby depriving himself of his freedom. When this happened, we spoke of a minor capitis deminutio.

This capitis deminutio, is called interchangeably: capitis deminutio media, or capitis deminutio minor; and both meanings correspond to the same legal situation, that of exclusion of the individual from Roman civil society, either because the individual voluntarily decides, before which he is no less than any pilgrim, or because a penalty compels him.

This would be the case of injunctions for water and fire, which were deprived of their citizenship, and that of those who voluntarily acquired another citizenship, and were no longer considered Roman─dicatione.

Minor sive media est capitis diminutio, cum civitas amittitur, libertas retinetur; quod accidit ei, cui aqua et igni interdictum fuerit

(However, the capitis deminutio is less, where citizenship is lost, retaining freedom, in what falls, as by the injunction of water and fire)

Gayo [3]

(Translation from the author*)

[3]: Gayo | Institutions: Lib. 1, Sec. 161.

Finally, if an individual became a slave, we speak of a maximum deminutio capitis. The condition of slavery in itself deprives him of any other right that he may have, which is why it is the most burdensome case of the loss of capacity of the individual.

This case operated, regardless of the individual's previous condition before becoming a slave, so for example, if this was previously a paterfamilias, homo optimus iure, or was a simple pilgrim─who only possessed his freedom─we also speak of a capitis deminutio maximum.

Since the legal presupposition that the Romans made for the construction of all other rights, was freedom. Without it, the individual was but one thing.

Maxima est capitis diminutio, cum aliquis simul et civitatem et libertatem amittit; quae accidit incensis, qui ex forma censuali venire iubentur: Quod ius, qui contra eam legem in urbe Roma domicilium habuerint; item feminae, quae ex senatus consulto Claudiano ancillae fiunt eorum dominorum, quibus invitis et denuntiantibus cum servis eorum coierint

(The capitis deminutio is maximum, when at the same time citizenship and freedom are lost, in what falls due to the expulsion of the census, which is given by a census order: what in law is to inhabit a home against the laws of the city of Rome; also the woman who becomes the slave of another by the Claudian senate, who despite being denounced did not cease the relationship with her slave)

Gayo [4]

(Translation from the author*)

[4]: Gayo | Institutions: Lib. 1, Sec. 160.

The capitis deminutio, could operate on any person, and with this we already presuppose that the person should be a free man, since slaves were legally things, but not people; so, they neither had rights to lose, nor did they have the ability to have them.

Regarding the people on whom it operated, it always did so in a personal capacity, affecting only the person who suffered the deminutio, whom we call capite minutus . This affectation was on an attribute of his personality, and therefore could not be delegated to another.

In addition, it did not always operate in the same way, but rather, according to the attribute of the affected personality, so it was progressive, the more vital the attribute was to guarantee the person their rights, the more burdensome was the capitis deminutio. that the person suffered.

And finally, it was always a sign of injury in the personality of the person who suffered it, so we say that it was unfavorable. Well, it is not possible for it to operate, without the capite minutus putting itself in worse condition than before.

In other words, that capitis deminutio always describes a grievance, in any degree, on the legal status of a person.

Although depending on the severity of the capitis deminutio, it has different causes, which have already been described each in the types of capitis deminutio, [¶] we can group all the ways in which a person could have their legal capacity affected in─at least─four groups.

The first, and perhaps the most emblematic way, in which capitis deminutio would operate, are (a) penalties; When a Roman citizen, by committing a serious act, or by fulfilling an obligation with a noxal clause, was defeated in a trial, he generally lost his freedom, or his citizenship, generating a maximum capitis, or an average.

Out of grief, however, only the family status could not be lost, so there was no minimal capitis in these cases.

The second, which is captivity, is a special case of capitis deminutio, because although captivity robs the person of their freedom, it does so only while it lasts, restoring in the head of those who managed to get out of captivity, the rights they had. before.

The third would be changes in the family status, especially those that are made voluntarily, because although with these, although the person changes their status to a new one, perhaps beneficial for them, they always imply affecting their spontaneous condition as agnate to a family, so you inevitably lose the advantages of this condition.

And finally, the loss of citizenship, which in itself, and by the mere fact of excluding the person from Roman society, represents an injury to their legal personality.

The person who suffered from a capitis deminutio, passed de jure and ipso facto to occupy a different and lower social status. For this the magistrate order did not mediate, but the loss of the attribute that constituted the recognition of that civil status.

Thus, if a person lost (a) their own legal autonomy, they went from being sui iuris to alieni iuris ; (b) his citizenship changed from being a Roman citizen to being a non-citizen; and (c) if he lost his freedom, he went from being a free man to a slave.

The consequence of this loss also implied the cancellation of many legal situations that required the permanence of the attribute, such as assets owned or legal businesses.

An exception was the ius postliminii in which the fiction operated that the person─who had been in captivity─had never lost his freedom as a war slave.

AcademiaLab© Actualizado 2024

This post is an official translation from the original work made by the author, we hope you liked it. If you have any question in which we can help you, or a subject that you want we research over and post it on our website, please write to us and we will respond as soon as possible.

When you are using this content for your articles, essays and bibliographies, remember to cite it as follows:

Anavitarte, E. J. (2019, December). The Capitis Deminutio in Roman Law. Academia Lab. https://academia-lab.com/2019/12/23/the-capitis-deminutio-in-the-roman-law/

In the Roman law, patria potestas or patria potestad is the institution of civil law that represents the power of paterfamilias over the people and property... (leer más)

It can be understood by sui iuris, any person whose rights and their exercise depend on their own legal status. That is, the rights he claims belong to... (leer más)

The ius civilis or ius civile, constituted all that right that the Romans considered their own, either because it had been created democratically in the... (leer más)