Objections at the Trial Stage

Objections are the guarantee that attorneys have to control the direct examination or cross-examination process of their... (leer más)

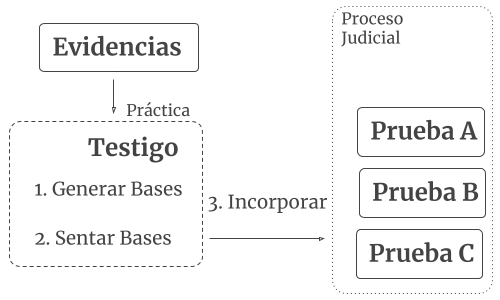

Until before the oral trial hearing, there is no evidence in the process: only physical phenomena ─ exhibits, testimonies, documents ─. This to guarantee the accused procedural principles such as immediacy, defense and contradiction; since these phenomena, even if it seems conducive, may be flawed by multiple circumstances, and not demonstrate the criminal responsibility of the accused.

To convince the judge, or the jury, the public prosecutor has the burden of supporting its theory of the case with suitable means of proof, which allow it to build a credible and convincing narrative of the criminal responsibility of the accused. And the defense, the duty to take an active attitude to maintain the presumption of innocence of the client.

It should be remembered that in the adversarial model the burden of proof falls exclusively on the parties, and not on the judicial apparatus. So the role of the judge is to determine whether the ─ up to that time ─ evidence can prove the claims of the parties.

To integrate the evidence into the trial, the lawyer must follow a series of logical and coherent steps that demonstrate the suitability of the evidence to be considered as evidence.

In general, this process has 3 phases: (a) identification of evidence, (b) authentication of evidence, and (c) presentation for the trial.

This introduction process must recreate a logical and coherent narrative, which lays the foundations on the suitability of the witness, in order to determine the authenticity of the evidence that will be incorporated. First, (a) placing the witness materially in the place where the evidence was located, this is to identify the evidence.

Then, (b) determining how this witness can provide information to the judge, and to the jurors, that allows them to recognize the evidence is the same as the one discussed, and has not been altered ─ is authentic ─, so it can be safely introduced, as a material evidentiary element, which will be taken a criterion for the ruling.

And (c) then yes, proceed to introduce them.

The first thing that should be done is to build a previous story about the context in which the evidence was generated, with clear-about questions, but not explicit, since the witness should not make random statements, which are not guided by the lawyer, because this can confuse the judge or jury, and undermine the credibility of the introducing process.

The judge and jury are required to understand why the witness is suitable for introducing the evidence, and for this, it is first necessary to place the witness where the evidence can be identified. The judge or jury must see credible why the witness knows that information, for example:

─ ... Where were you, Miss Barbara? ─

─ I was right in front of the pool, cleaning the floor ─

─ What time was it when you cleaned the floor? ─

─ It was already 4:30 pm, and I already wanted to go home, but ... ─

─ But what? ─

─ But, well ... it was the moment when the shot rang out ... ─

After having given context to the witness, he or she must announce the evidence, since in accusatory systems, where the judge is not personally involved in the collection of evidence, the evidence is only incorporated through the witnesses as sponsor.

Especially those witnesses who only sympathize to try to incorporate physical evidence, called accreditation witnesses. Since these are the "direct source of factual knowledge".

To announce the evidence, the witness must describe, not too much detail, the evidence, and how he could perceive it, for example:

─ ... And then what did you see? ─

─ I saw a gun... and... next to it was... Mrs. Jennifer ─ (the witness cries).

─ Calm down, Mrs. Barbara, please tell the judge what the weapon was like ─

─Well, the weapon was like gray, and I think... black too, it looked like a revolver and had a red skull ─

At this time, the witness has already generated enough probative bases, has already managed to place the evidence in the place of occurrence of the events, and in the context of his own story and credibility, so that it is possible to move on to the second moment of the incorporation: authentication of the evidence.

After having identified the evidence, which is to bring the evidence to the procedural world, now we proceed to authenticate them, which is to demonstrate before the judge, or the jury, that the evidence is authentic and corresponds to what the witness has already mentioned and seen.

We call this authentication, since it is on the accreditation of the witness and the authenticity of the evidence that the request to the judge for admitting them as evidence at the trial is supported.

To do this, the judge must be asked to show the exhibits, in order to tender them to the witness, and continuing talking about them. This petition is simple, and only requires that the evidence have already been identified.

─Your Honor, allow me to tender evidence number 003 to the witness, and continue with the testimony ... ─

It is a good practice that the exhibits are previously numbered, in order to be able to refer them without having to use all the necessary adjectives to be able to delimit it. For example, it is not the same to say "exhibit number 003" as to say "the torn, blue trousers, 1.8 m long, owned by the deceased," or even worse, to say only "the trousers".

The most usual thing, if the objectives of step number 1 ─ identifying the evidence ─ were faithfully met, is for the judge to accept the tender of the evidence, unless the other party objects. If the counterpart objects, and the judge agrees, logically it was not fulfilled the identification. [¶]

With the witness having materially the evidence, we proceed to establish the authenticity, which is nothing else, than to prove the sameness and chain of custody of the evidence.

The objective is for the judge or jury to understand that the evidence mentioned above, during the identification of the evidence, is the same that the witness has in their hands. For this ─ continuing with the example of Mrs. Barbara ─ we proceed to interrogate:

─ ... Do you recognize what I have given you? ─

─ Yes sir ─

─ What is it, please? ─

─ It is the weapon lawyer, it is the weapon, this is the weapon, it is the weapon... ─

─Thank you, Mrs. Barbara, but please calm down, why do you know that is the weapon? ─

─ Look here ... (shows the weapon) there is the red skull, it is exactly the same... ─

To this, all the necessary questions will be added so that the judge knows that the evidence, which everyone can see at the hearing, is the same referenced for the witness.

Achieving, in this way, to link the witness with the evidence, no longer from a story, but from the tangible experience in front of the judge and jury.

Already having firm authentication, comes the more technical aspect in the process of introducing the evidence, which no longer deals with the experience of the witness, but with the rules of evidence. These criteria are two: (a) authenticity, and (b) relevance.

By relevance, it is understood that, although the witness places the evidence in the trial, it must also be relevant, pertinent, capable of proving legal facts that lead to clarify criminal responsibility, and be incorporated by the appropriate means and witnesses. The other party may object to all this.

And by authenticity the evidence is understood that it must be possible to demonstrate that the evidence is in the same condition as when it was at the scene. Well, the witness can see the same evidence, but it may have been altered over time.

Authenticity is especially important when using evidence that has to have a scientific process prior to trial, to know a certain fact. Here comes the concept of chain of custody.

Continuing with the example of Mrs. Barbara, suppose that there is already an evidentiary stipulation in favor of the authenticity of the evidence, so that the chain of custody cannot be opposed.

─ Mrs Barbara, are you sure it is the same weapon? ─

─ Well, lawyer, I only saw her until the members of the police took her away ─

─ How long were you at the scene of the crime? ─

─ More or less five hours... is that... how was I going from there─

─ And since what time were you there? ─

─ Since five in the morning... (looks at the jury) ─

In this case, it is clear that Barbara is the ideal one to relate the weapon with the person being charged, because she knows the place, she was there all day, and waited for the police, she could also give us more detailed data of the origin of the weapon.

─ And do you know whose weapon it is? ─

─ I think from Don Armando, because look... (points to something on the gun) ─

─ Please tell the jury, what is that─

─ It's just that, Don Armando puts this red skull over all his weapons ─

And already at this point, the evidence can be introduced, provided that the evidentiary stipulation about the chain of custody have been read, after the witness.

The incorporation would proceed more or less like this:

─ Your Honor, I request that this exhibit, number 003, be incorporated as evidence number 001 of this trial ─

In general, the common framework that enable the process for introducing evidence in any common law country, is the personal practice of the evidence, that is mean: without mediation, facing directly the jury, the judge, the witness, the prosecutor, and the defense; and the rules of evidences, are precisely a way to get this orderly and legally.

Rules of evidence changes in every country, jurisdictions and districts, but the warranty continuing to be the same, there is no evidence for the court until their personal practice, whereby the jury and judge can see the evidences, and the counterpart can oppose to them.

This core feature of the common law systems can be dated until the thirty-nine article of the Magna Carta of the United Kingdom ─ by the lawful judgment of his peers ─, followed by the sixth Amendment of the United States Constitution ─ right to a speedy and public trial, by an impartial jury ─.

This is called as principle of immediacy in the civil law systems, and in another countries with mixture characteristics as India is called personal hearing.

AcademiaLab© Actualizado 2024

This post is an official translation from the original work made by the author, we hope you liked it. If you have any question in which we can help you, or a subject that you want we research over and post it on our website, please write to us and we will respond as soon as possible.

When you are using this content for your articles, essays and bibliographies, remember to cite it as follows:

Anavitarte, E. J. (2015, October). Steps for Introducing Evidence at Criminal Trial. Academia Lab. https://academia-lab.com/2015/10/04/steps-for-introducing-evidence-at-criminal-trial/