Yayoi period

The Yayoi period (弥生時代, Yayoi-jidai?) or 彌生時代 (old form of the first kanji for Yayoi) is the era in Japanese history that follows the Jōmon period and precedes the Kofun period, spanning about 550 years, from the year 300 B.C. C. to 250. This name is due to the place where the first ceramics that characterize its time were found, Yayoi in Tokyo.

They developed metal and ceramics, unlike the Jōmon period, which was more elaborate with some patterns. Rice cultivation begins, very important for Japanese development. The first signs of the introduction of Shinto appear at the end of the period.

Yayoi culture flourished in a geographic area from southern Kyūshū to northern Honshū. Archaeological evidence supports the idea that during this time, an influx of farmers (Yayoi people) from the Korean peninsula arrived in Japan, and mixed with or pushed aside the native population of hunter-gatherers (Jōmon people). Modern Japanese are descendants of the Yayoi people, with only a very small to moderate influence from the ancient Jōmon, depending on the region.

Features

It is generally accepted that the Yayoi period dates from 300 BCE. C. to 300 d. However, radiocarbon evidence suggests a date of up to 500 years earlier, between 1000 BCE. C. and 800 a. C. During this period, Japan made the transition to an established agricultural society.

The earliest archaeological evidence of the Yayoi is found in northern Kyūshū, but this fact is still debated. The Yayoi culture spread rapidly to the main island of Honshū, mixing with the native Jōmon culture. A recent study using accelerator mass spectrometry to analyze charred remains on pottery and wooden stakes, suggests they date back to the IX a. C., 500 years earlier than previously believed.

Crafts

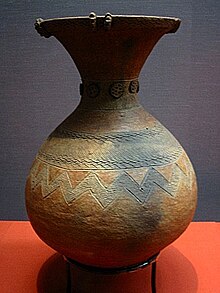

[[File:DotakuBronzeBellLateYayoi3rdCenturyCE.jpg|thumb|left|A dōtaku bell from the III century a. c. The name Yayoi is borrowed from a location in Tokyo where pottery from the Yayoi period was first found. Yayoi pottery was simply decorated and produced using the same rolling technique previously used on Jōmon pottery. in Yayoi crafts they made ceremonial bronze bells (dōtaku), mirrors and weapons. In the I d. C., the inhabitants of Japan began to use agricultural tools and iron weapons.

Organization of society

As the population increased, society became more stratified and complex. They wove textiles, lived in permanent farming villages, and built buildings out of wood and stone. They also accumulated wealth by owning land and storing grain. Such factors promoted the development of different social classes. Contemporary Chinese sources described people as having tattoos and other body markings indicating differences in social status. Chieftains, in some parts of Kyūshū, appear to have sponsored and politically manipulated the trade in bronze and other prestigious objects. This it was made possible by the introduction of irrigated wet rice agriculture from the Yangtze estuary in southern China through the Ryukyu Islands or the Korean Peninsula. Thus, wetland rice agriculture led to the development and growth of a sedentary agrarian society in Japan.

Archaeological evidence also suggests that frequent conflicts between settlements or states broke out during the period. Many excavated settlements were built in moats or on the tops of hills. Headless human skeletons discovered at the Yoshinogari archaeological site are considered typical examples of finds of the time. In the coastal area of the Seto Inland Sea, stone arrowheads are often found among grave goods.

Agriculture

Agriculture developed mainly through the introduction of efficient tools, the flooding of fields, and the use of ditches and granaries. At first, it was only cultivated in low-lying areas to take advantage of the floods, but with improved technology, higher lands could be used. The division into large plots by means of wooden boards was common. Food used to be stored in jars, but granaries were developed to store it. In this way, they built wooden buildings a few meters above the ground to prevent rodents from reaching the harvest.

Inhabitants

Direct comparisons between the skeletons of Jōmon and Yayoi people show that the two peoples are remarkably distinguishable. The former tended to be shorter, with relatively longer forearms and calves, eyes farther apart, shorter and broader faces, and a much more pronounced facial topography. They also have strikingly raised eyebrows, noses, and nasal bridges. People who lived during the Yayoi era, on the other hand, were 2.5 to 5 cm taller, with closely set eyes, tall narrow faces, and flat noses and eyebrows. In the Kofun period, almost all excavated skeletons in Japan, except those of the Ainu, are of the Yayoi type and some have a small admixture of Jōmon, resembling those of present-day Japanese.

History

Origin of the Yayoi people

The origin of the Yayoi culture and its people has been debated for a long time. The earliest archaeological sites are Itazuke or Nabata in the northern part of Kyūshū. Contacts between the fishing communities of this coast and southern Korea date back to the Jōmon period, as evidenced by the exchange of trade items such as fish hooks and obsidian. During the Yayoi period, cultural elements from Korea and China arrived in this area in various forms. times for several centuries and then spread south and east. This was a time of mixing between immigrants and indigenous populations, and between new cultural influences and existing practices. Chinese influence was obvious in bronze and copper weapons, dōkyō, dōtaku, as well as in the cultivation of rice with irrigation systems.

However, some scholars argue that the rapid increase of approximately four million people in Japan between the Jōmon and Yayoi periods cannot be explained by migration alone. They attribute the increase mainly to a shift from a hunter-gatherer diet to an agricultural diet on the islands, with the introduction of rice. It is very likely that the cultivation of rice and its subsequent deification allowed for a slow and gradual increase in population.

Appearance of Wa in Chinese history texts

The earliest written records of people in Japan come from Chinese sources from this period. Wa, the pronunciation of an early Chinese name for Japan, was mentioned in AD 57. C., when the state of Na received a gold seal from Emperor Guangwu of the Han Dynasty. This event was recorded in the Book of Later Han, compiled by Fan Ye in the fifth century. The seal itself was discovered in northern Kyūshū in the 18th century century. Wa was also mentioned in 257 in the Wei zhi, a section of the Records of the Three Kingdoms compiled by the century scholar III Chen Shou.

Early Chinese historians described the Wa as a land of hundreds of scattered tribal communities, rather than the unified land with a 700-year tradition set forth in the century's work VIII Nihon Shoki, a part-mythical, part-historical account of Japan dating back to its founding. of the country in 660 a. c.

Yamataikoku

[[File:Hashihaka-kofun-1.jpg|thumb|right|Tomb of Hashihaka, Sakurai]] The Wei Zhi first mentions Yamataikoku and Queen Himiko in the 3rd century. According to the record, Himiko assumed the throne of Wa, as spiritual leader, after a great civil war. Her younger sister was in charge of state affairs, including diplomatic relations with the Chinese court of the Kingdom of Wei.

For many years, the location of Yamataikoku and the identity of Queen Himiko have been the subject of investigation. Two possible locations have been suggested: Yoshinogari in Saga Prefecture and Makimuku in Nara Prefecture. Recent archaeological investigations in Makimuku suggest that Yamataikoku was located in the area. Some scholars assume that the kofun Hashihaka in Makimuku was Himiko's grave. The relationship of her to the origin of the Yamato polity in the following Kofun period is also up for debate.

Additional bibliography

- Habu, Junko (2004). Ancient Jomon of Japan (in English). Cambridge, MA: Cambridge Press. ISBN 978-0-521-77670-7.

- Schirokauer, Conrad (2013). A Brief History of Chinese and Japanese Civilizations (in English). Boston: Wadsworth Cengage Learning.

- Olivier Brunet; Charles-Édouard Sauvin (2016). Les marqueurs archéologiques du pouvoir; chapter: Les miroirs sankakubuchi shinjū: témoins de l’émergence d’un pouvoir centralisé dans le Japon protohistorique (s-III-IV) - Linda Gilaizeau. (Publications de la Sorbonne) OpenEdition Books. pp. 49-56. Linda Gilaizeau 2016..

See also: Gilaizeau L. (2010), Le rôle et l’influence du continent asiatique sur les sociétés de l’archipel japonais durant la protohistoire à travers les pratiques funéraires. Du Yayoi moyen au Kofun ancien (s V avant notre ère – s IV de notre ère), Ph.D. Thesis of the University of Paris I – Panthéon Sorbonne, unpublished. - Vicki Cummings; Peter Jordan; Marek Zvelebil (2014). The Oxford handbook of the archaeology and anthropology of hunter-gatherers (in English). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-955122-4..

- Jean Paul Demoule (2009). La Révolution néolithique dans le monde, Séminaire du Collège de France (in French). Paris: CNRS éditions. ISBN 978-271-06914-6. La Révolution néolithique dans le monde 2009.with the participation of Laurent Nespoulous, «Le contre-exemple Jōmon», p. 65-85.

- Junko Habu (2004). Ancient Jomon of Japan (in English). Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, etc.: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-77670-8. Junko Habu 2004.. Also: ISBN 978-0-521-77670-7 (br.). -ISBN 978-0-521-77213-6. Another edition in 2009.

- Francine, Hérail; Carré, Guillaume; Esmain, Jean; Macé, François; Souyri, Pierre (février 2010). Histoire du Japon, des origines à nos jours (in French). Paris: Éditions Hermann. ISBN 978-2-7056-6640-8. Hérail 2009. The reference uses the obsolete parameter

|mes=(help). - Mark J. Hudson (2009). A Companion to Japanese History, Japanese Beginnings. Wiley Blackwell Companions to World History (in English). John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9781405193399.

- Imamura, K. (1996). Prehistoric Japan, New perspectives on insular East Asia (in English). London: University College London. ISBN 1-85728-616-2. Keiji Imamura, 1996. Identical edition: University of Hawaii Press, 1996, 246 pages, ISBN 0-8248-1853-9

- Kumar, Ann (2009). Globalizing the prehistory of Japan, language, genes and civilization. Studies in the Early History of Asia (in English). London; New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-7103-1313-3. Ann Kumar, 2009.

- Naoko Matsumoto; Hidetaka Bessho; Makoto Tomii (2012). id=Shinpei Hashino, 2012 Coexistence and Cultural Transmission in East Asia, chapter=10 Shinpei Hashino: The Diffusion Process of Red Burnished Jars and Rice-Paddy Field Agriculture from the Southern Part of the Korean Peninsula to the Japanese Archipelago. One World Archaeology (in English) (61). pp. 203-222..

- Naoko Matsumoto; Hidetaka Bessho; Makoto Tomii (2011). Coexistence and Cultural Transmission in East Asia; chapter: Yoichi Kawakami: The Imitation and Hybridization of Korean Peninsula-Style Earthenware in the Northern Kyushu Area during the Yayoi Period (in English). Left Coast Press. pp. 257-276. Yoichi Kawakami, 2011..

- Koji Mizoguchi (2013). The archaeology of Japan, from the earliest rice farming villages to the rise of the state. Cambridge world archaeology (in English). New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-88490-7. Mizoguchi, 2013..

- Koji Mizoguchi (2002). An archaeological history of Japan, 30 000 BC -to AD 700 (in English). Philadelphie: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 0-8122-3651-3. Mizoguchi, 2002.

- Christine Schimizu (1998). L'Art japonais. Vieux Fonds Art (in French). Paris: Groupe Flammarion. ISBN 2-08-012251-7. Christine Shimizu, 1997.and Schimizu, Christine (2001). L'Art japonais. Tout l'art, Histoire (in French). Paris: Groupe Flammarion. ISBN 2-08-013701-8. Christine Shimizu, 2001.

- Werner Steinhaus; Simon Kaner (2017 (ed. 2016)). An Illustrated Companion to Japanese Archaeology: Comparative and Global Perspectives on Japanese Archaeology (in English). Archaeopress Archaeology. ISBN 978-1-78491-425-7. Steinhaus et Kaner, 2017.. With numerous illustrations in color, maps and plans and text almost reduced to the commentary of the illustrations

Contenido relacionado

Hatshepsut

Breakbeat

Zapatista