Wiphala

The wiphala is a quadrangular flag of seven colors, originally used by Andean peoples and later adopted by other indigenous peoples such as the Guarani; present especially in Bolivia, in some regions of Peru, Colombia, in northern Argentina and Chile, southern Ecuador and western Paraguay.

In Bolivia it is recognized as a national symbol, since February 7, 2009, through the 2009 Constitution, and regulated by Supreme Decree No. 241 of August 5, 2009; it is hoisted to the left side of the Bolivian national flag.

In Chile it is recognized as a symbol of the Alto Hospicio commune, since October 3, 2017, it is hoisted on the left side of the Chilean national flag and the communal flag.

In Peru, since July 15, 2022, it is recognized as a symbol of the original Quechua, Aymara, Uros and mestizo peoples in the Puno region.

In Argentina through the Argentine Constitutional Reform of 1994, the use of the wiphala is allowed on the condition that the pre-eminence of the national and provincial flags is recognized, being hoisted on the left side of said flags; in the province of Catamarca, province of Chaco, province of Jujuy, province of Tucumán and the city of Salta, normally on commemorative dates and government ceremonies.

Etymology

It is likely that the word wiphala comes from two words in the Aymara language:

- wiphai (/wiphai/), exclamation of triumph, used so far in solemn feasts and ceremonial acts;

- lapx-lapxproduced by the effect of the wind, which originates the word laphaqi (laphaqi/) which is understood as the wave of a flexible object by wind action.

From both arises the term wiphailapx; "the triumph that undulates in the wind". For euphonious reasons, the word became wiphala.

Other names

Wiphala is called by several other names:

- laphaqay (lapJakJai/), by the kallawayas in the department of La Paz (Bolivia).

- laphala (lapJala/), in the regions of the department of Potosí (Bolivia).

- wiphayla (/uipJaila/), in the valleys of the department of Cochabamba (Bolivia).

- wipala (/uipála/), in some regions of Ecuador.

- wipala in Argentina

- wifala (/wifala/), in Arequipa (Peru).

History

Pre-Columbian origins

The pre-Columbian peoples of the Andes mountain range did not lack their own symbols (especially those of state tradition, such as the Inca Empire), but the format of a "quadrilateral cloth banner" to wave in the wind is not an American tradition but rather of the Old World. For this reason, the pre-Columbian origins of the wiphala should not be located as a flag but as a recurring design in pre-Hispanic symbology.

The oldest surviving example of a wiphala-type design corresponds to a chuspa or coca bag from the Tiahuanaco culture (1580 BC-1187 AD). Its use of the wiphala design is found in mixed with several others so it is not possible to establish its meaning or use within the Andean cosmogony of the time.

The Museum of World Culture in Gothenburg, Sweden, contains a fabric with a wiphala-like design dating from the 11th century. It originates from the Tiahuanaco region, and is part of a collection based on the tomb of a Kallawaya healer.

- In the Tiwanaku Museum of the Department of Peace there are two wiphalas painted in a qiru (vaso).

- In the province of Antonio Quijarro (department of Potosí) there is a wiphala next to tissues in koroma.

- In a place called Wantirani, in Qppakati (province Manko Kapajk, in the department of La Paz), there is a wiphala painted on a rock.

Use during the Viceroyalty

The use of the wiphala as a banner seems to have originated to some extent during the colonial period. There are two representations of angels made in the style of the Cuzco school. The first is a painting from the 18th century, titled Gabriel Dei and located in the Church of Calamarca, it shows the angel Gabriel as an arquebusier carrying a checkered flag very similar to the figures of the pre-Columbian quiru.; the painting is possibly by the Master of Calamarca. The second is an untitled painting from the XVII or century style="font-variant:small-caps">xviii.

There is also an example of a checkered flag in the 1716 painting Entrada del Virrey Arzobispo Morcillo en Potosí, currently preserved in the Museo de América in Madrid.

Use in the Republic of Bolivia

The oldest description of the wiphala during the republican period comes from the French naturalist Alcide d'Orbigny who in 1830 described the following scene during the festivities of San Pedro in La Paz, in an area with an Aymara majority for the time:

There was also an accompaniment, three landscapes, arranged with a large tahalí hanging from the neck and two bearing banners carrying a white, yellow, red, blue and green flag.

Despite the many representations of the wiphala in Andean art since the pre-Hispanic period, the first documented mention of its use with its own name and an explicitly indigenous character comes from Alberto de Villegas in 1931:

I would have wished to send you a Chaski, with this message from Tambo in Tambo, to the city. I would like to crown with fire the serranies, in the warmth of these nights of December, or to resonate in the rough puna the insistent cry of the pututo, to summon them to the celebration of the next inti raymi [sun party, in the winter solstice] on the banks of the Chekheyapu. Proclaimed by force of the circumstances, the Gonfaloner of Indianism in La Paz, I'm waving the wiphala, old flag of the Aymaras.from the now broken isolation of my pukara.

Federal War (1898-1899)

There is documentation from the Federal War where it indicates that Pablo Zárate Villca and other indigenous people used whipalas, although of different colors or with fewer colors.

[...] the flag that rose Pablo Zarate Villca was 11 for 12 squares [... ]

Indigenist Congress (1945)

On November 17, 1944, the organization of the First Bolivian Indigenous Congress began. Among those who organized it was the traditionalist and aimarólogo Hugo Lanza Ordóñez. He pointed out to the audience that the existence of the word wiphala suggested that there must always have been some kind of flag in Andean culture, so he decided to use a white flag (the only one known by then in important events). Another congressman, Germán Monrroy Block, opined in favor of using a more colorful flag, in keeping with the Aymara aesthetic.

The printer Gastón Velasco recalled that years before he had designed a label for the Champancola brand, which was a soft drink company created in the late twenties in La Paz, the first of its kind. Its owners were two Italian citizens, Salvietti and Bruzzone. This factory produced a sparkling soft drink like champagne, without alcohol, which they gave the name Champancola (champagne-cola). The bottle had a small glass ball at the neck that -by the force of the gas- covered the container hermetically. An employee of the factory -also Italian, with the last name Sorrentino- sold soft drinks through the streets of La Paz in a cart pulled by a donkey. The label printed by Velasco from La Paz was a square made up of other smaller squares with the most diverse colors. Based on that design, the three movement compañeros created the flag of the first indigenous congress.

Between May 10 and 15, 1945, the congress was held at the Luna Park sports arena in the city of La Paz, which brought together more than a thousand delegates of native peoples from the western and eastern sectors of Bolivia. The then President of Bolivia, Major Gualberto Villarroel, took the provisions of this congress and published them as decrees.

Pongueaje and all free work (slave labor) were abolished. Many colonists stopped serving their exploiters and suspended agricultural work on the haciendas. Many indigenous people were persecuted and confined to inhospitable places like Ichilo (in Santa Cruz) and Coatí Island in Lake Titicaca. However, the idea of recovering their ancestral lands, in the hands of the exploiters, became widespread among the indigenous people.

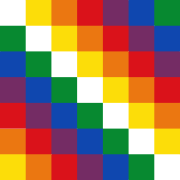

Contemporary Design (1979)

In 1979 Germán Choque Condori, also known as Inka Waskar Chukiwanka, known as the "restorer of the wiphala" o "rediscoverer of the whipala", designed the contemporary wiphala, which consists of 7 colors and 49 quadrants, based on recurring designs in the Andean symbology of quadrants or chess designs that are found in fabrics or ceramics from pre-Hispanic periods; The colors adopted for his contemporary wiphala is based on a story by a chronicler named Santa Cruz Pachacuti between 1612 and 1613, who wrote about a symbolic moment when Manco Cápac left Lake Titicaca in which the crossing of two rainbows was observed, hence that relates the 7 colors.

When Manco Kápac left Lake Titicaca heading to Cuzco he saw from a hill two rainbows, female and male, whose union expressed the 49 colorful squares, in that way the rainbow is related to the wiphala.Germán Choque Condori

Although for the perception of the Quechuas (during the Incas) the rainbow only had 4 colors, and not 7 colors; the perception of 7 colors in the rainbow comes from a theory by Isaac Newton.

Initially, this new design was only used at the Universidad Mayor de San Andrés, by the Julián Apaza University Movement (MUJA) led by Raymundo Tambo. MUJA, as an indigenous front, always claimed the wiphala within the university, later this design began to become popular among Bolivian indigenous movements and other parts of South America.

Use in Bolivia

In Bolivia, the wiphala is recognized as a national emblem since February 7, 2009, in the Political Constitution of the State of 2009, and its use, colors and proportions are regulated by D.S. No. 241, August 5, 2009. This must be hoisted on the left side of the Tricolor Flag.

Recognition as a national symbol of Bolivia (2009)

After a constitutional referendum, the 2009 Constitution was approved, in which the wiphala is recognized as the national symbol of Bolivia. Article 28 states that it is a "sacred symbol that identifies the community system based on equity, equality, harmony, solidarity and reciprocity."

The symbols of the State are the red, yellow and green tricolor flag; the Bolivian anthem; the coat of arms; the wiphala; the scarapela; the flower of the kantuta and the flower of the patuju.Article 6 (II) of the Political Constitution of the State of Bolivia of 2009

In 2017, the flag of the Maritime Claim was modified, adding the Wiphala next to the Tricolor:

The Bandera de Reivindicación Maritime del Estado Plurinacional de Bolivia, consists of blue sea field; in the upper left quadrant the Tricolor Flag next to the Wiphala, with nine small stars of five golden tips around and in the lower right quadrant a medium star of five golden points.Art. 4, Act No. 920

The Maritime Claim flag is also the flag of the Bolivian Navy; The Whiphala is the war flag and is part of the shield of the Bolivian Army.

Conflicts in Bolivia (2019)

During the political conflict that Bolivia experienced between October 21 and November 22, 2019, due to accusations of fraud in the October 20 elections, and the subsequent resignation of Evo Morales; Some groups opposed to the MAS government (Evo Morales' political party), among them uniformed policemen, burned or cut whipalas. In response, organizations in the city of El Alto responded by waving the constitutional symbol to the cry of “The wiphala is respected, damn it!” and “now yes, civil war!”. The crisis resulted in 30 deaths.

For this reason, the departmental commands of the Police throughout Bolivia, carried out an act of reparation to the wiphala, after the protests in which the national symbol was burned.

"Those nations that felt offended by the act of a policeman should know that it is not the feeling of the institution, that the Police is committed to its people, with everyone without reason of race, sex or idiosyncrasy&# 34;, said the police commander in Cochabamba, Jaime Zurita.

Both in the city of La Paz and El Alto, the wiphala was used in homes, businesses or vehicles as a symbol of protest or to protect themselves from attacks, in homes in the city of El Alto the motto & #34;the wiphala is respected".

Proportion and dimensions

Respecting the implication of the number seven in the Wiphala proportions, the dimension of each of the squares that compose it must be related to the number seven and its multiples.

Colors

Supreme Decree No. 241 of August 5, 2009, establishes the following color tones as official, for the wiphala adopted by the Bolivian State:

| Denomination | White | Green | Blue | Violeta | Red | Orange | Yellow |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pantone | No code | 356 - C | 286 - C | 266 - C | 485 - C | 165 - C | P - CVU |

| RGB | 255-255 | 0-121-52 | 0- 50-160 | 117- 59- 189 | 191-4-17 | 255- 103- 32 | 254-238-0 |

| CMYK | C0-M0-Y0-K0 | C100-M0-Y57-K53 | C100-M80-Y0-K12 | C71-M88-Y0-K0 | C0-M100-Y100-K0 | C0-M60-Y87-K0 | C0-M0-Y100-K0 |

| HEX | #ffff | #007934 | #0032a0 | #753bbd | #DA291C | #ff6720 | #F9E300 |

Use in public institutions

The Wiphala is raised on the left side of the front of the buildings of Bolivian public institutions. The official dimensions of the Wiphala are as follows:

- to flame: 245 centimeters high by 245 wide, each frame being 35 square centimeters.

- for each vehicle and desk: 24.5 centimeters high by 24.5 centimeters wide, each box being 3.5 cm square.

Use of educational units and training center

In educational units, public and private universities and other training centers, the Wiphala is displayed on the left side of the front of their respective buildings.

General use

- In public holidays and patriotic commemorations, the civilian population can raise the Wiphala on the left side of their properties, and this right is extended to foreigners who want to do so.

- The Wiphala can be placed on the coffin of eminent and distinguished citizens or who have lost their lives in service to the Bolivian State, without touching land.

- The representation of Wiphala as a badge can be placed on the left side of the chest, this badge can accompany the flag of the Tricolor Flag.

Variant

There is an official variant of the wiphala, this is a union of four wiphalas whose white diagonals form a chacana or white Andean cross that appears in the center.

Wiphala Banner

The Wiphala banner can take two forms:

- The Wiphala izada from the top angle of the white diagonal forming a cross with the asta.

- Union of four Wiphalas whose white diagonals form a white chacane or Andean cross that appears in the center.

Symbolism

The colors of the Wiphala have the following meaning:

D. S. No. 241, 5 August 2009Article 28:

ROJO: represents the planet earth, is the expression of people in intellectual development, is the cosmic philosophy in the thought and knowledge of the wise, all the visible material world.

NARANJA: represents society and culture, also expresses the conservation and procreation of the human species, considered as the most precious heritage wealth, is health and medicine, training and education, the cultural practice of dynamic youth.

AMARILLO: represents energy and strength, reciprocity and complementarity, is the expression of the moral principles of man - woman, are laws and norms, the collective practice of human solidarity.

BLANCO: represents time and dialectics: cyclical history, is the development of science and technology, art, intellectual and manual work that generates reciprocity and harmony within the community structure.

VERDE: represents the economy and production, symbolizes natural wealth, flora and fauna, hydrological and mineral resources to land and territory.

AZUL: represents space, cosmic energy, infinity, the spirit that animates everything.

VIOLETA: It represents social and community politics and ideology, the state, as a higher instance, the power structure, social, economic and cultural organizations and the administration of the people and the nation.

War Flag

The flag of war is used in cases of armed conflicts or armed actions, by the Bolivian armed forces and police; since March 18, 2010, the wiphala has been adopted as the war flag.

Flag of maritime claims

The Maritime Claim Flag is an official flag of Bolivia, which contains the tricolor flag next to the wiphala in the upper left quadrant.

This flag is hoisted and used in civic and cultural events related to the Bolivian maritime theme, used in the month of March of each year, in offices of all State bodies, Armed Forces, Bolivian Police, public and decentralized entities. It is, in turn, the naval flag and war flag of the Bolivian Naval Force.

Use in Chile

Mint House

Since Gabriel Boric's ascension to the Chilean presidency, the Wiphala began to be hoisted at the La Moneda Palace, along with indigenous flags such as the Mapuche flag, the Quechua flag, and the Rapa Nui flag.[citation required]

Community of Alto Hospicio

On October 3, 2017, the commune of Alto Hospicio will declare itself as a multicultural commune; decreeing to be officially called “Multicultural Commune of Alto Hospicio”, therefore, the municipal council of the commune unanimously determined the recognition of the Wiphala as a symbol of the commune, which must be hoisted together to the Chilean flag and communal flag; Likewise, the creation of the office of indigenous affairs was determined.

Use in Peru

Regional Government of Puno

The Whiphala was used as an emblem of the management of Walter Aduviri Calizaya (2019-2020), as Regional Governor of Puno.

On August 14, 2019, the wiphala was hoisted instead of the Peruvian flag, in the infrastructure of the Regional Government of Puno, the event coincided when Aduviri was sentenced for the "Aymarazo" case, to 6 years in prison, while he was a fugitive.

On June 15, 2022, the whipala was declared a symbol of the original Quechua, Aymara, Uros and mestizo peoples in the Puno region.

Use in Argentina

The Argentine National Constitution in its reform of 1994, recognizes the Argentine indigenous peoples (article 75, paragraph 17) and guarantees their identity; This legal framework guarantees that by their own decision and without necessarily having any official recognition, they adopt the flags that they freely determine.

Consequently, the wiphala is used in Argentina, with the condition that the pre-eminence of the Argentine national and provincial flags is recognized.

Catamarca Province

On August 17, 2016, the Chamber of Deputies of the Province of Catamarca declared the institutionalization of wiphala in schools of said Argentine province.

Chaco Province

On April 20, 2011, the Chamber of Deputies of the Province of Chaco enacts a law authorizing the different Chaco ethnic groups to adopt it, until an Argentine Indigenous Congress defines its own flag.

Law 6.781 of 20 April 2011 (Chaco Chamber of Deputies)Art. 1: Recognize the Bandera Indigena Wiphala, as an emblem of the native peoples of America.

Art. 2°: It is determined that the flag recognized in Article 1 of the present, may be adopted by the ethnic groups of the territory of the Province of Chaco, until a indigenist congress defines an Argentine Flag, which represents the Aboriginal communities that inhabit the Argentine soil.

In 2016, it was established that all educational institutions incorporate the "Wiphala" as part of the symbols of the province and for official acts of the Executive Branch, as well as for sessions and official acts that take place in the Legislative and Judicial Branch.

Jujuy Province

In the Province of Jujuy it was established that every April 19 "American Aboriginal Day", June 21 "Inti Raymi" (Fiesta del Sol), during the month of August, in homage to Pachamama, Mother Earth, and on October 12 "Cultural Diversity Day", the wiphala is raised to the left of the national flag of Argentina and the flag of the Civil Liberty of Jujuy.

Article 1: To have in the Province of Jujuy, from the promulgation of this law, the symbol of the Indigenous Peoples, Wiphala, together with the National Flag and the Flag of Civil Freedom, is used and enarbole in public buildings, as well as in the legislature of the Province of Jujuy, the days: April 19 "Homage of the American Aboriginal, Ray, June 21" Article 4. -The symbol of the Wiphala will not be materially greater than the National Flag and the Flag of Civil Freedom that is used in a joint manner, being in an immediate position inferior to it, or in parallel to its left. In the ceremonial, precedence must be observed for the National Flag and the Flag of Civil Freedom.

Province of Tucuman

On May 18, 2017, the Tucumán Provincial Legislature modifies art. 7 of Law 8291, declaring the Wiphala as one of the three ceremonial flags of the province, along with the national flag of Argentina, the national flag of Civil Liberty and the provincial flag of Tucumán.

City of Salta

On July 11, 2014, through Resolution no. the Original Peoples, next to the national flag of Argentina and the provincial flag of Salta.

City of Rosario

Between November 25 and December 2, 2019, the wiphala was raised at the Monumento a la Bandera, by decision of the Deliberative Council of the city of Rosario, as a symbol of solidarity with the indigenous Bolivians, due to the repression of the government of Jeanine Añez in Bolivia.

Flags formed by Wiphala

Shields formed by the Wiphala

The shield of the Bolivian army has included the wiphala in its design since 2010.

Confusion with the Imperial Inca Banner

Usually the wiphala is attributed as the flag of the Inca Empire, which is incorrect, the closest thing to a flag, used in the Inca Empire, is the Inca imperial banner, which is a banner or tocapu used by the Inca sovereign during the Inca imperial period. It is worth noting that this emblem does not have an identical use to that of contemporary national flags, since it represented imperial power and the figure of the Inca or emperor.

16th- and 17th-century chronicles and references support the idea of an imperial banner:

Francisco de Jerez wrote in 1534 in his chronicle True account of the conquest of Peru and the province of Cusco, called New Castile:

... all of them were divided into their squadrons with their flags and captains who command them, with both concert and Turks.

The chronicler Bernabé Cobo wrote:

... the actual script or banner was a square and small banderilla, of ten or twelve pavements of rough, made of cotton or wool canvas, was placed in the auction of a long, woven and stiff ale, without waving to the air, and in it each king painted his weapons and currency, because each one of them seemed to be different, even though the generals of the Incas were the crownsBarnabas Cobo, History of the New World (1653)

Felipe Guamán Poma de Ayala's 1615 book, Primer nueva corónica y buen gobierno, shows numerous line drawings of Inca flags. In his 1847 book, Historia de la conquista del Peru, William H. Prescott says that "in the Inca army each company had its own standard and that the imperial standard, above all, showed the shining figure of the rainbow, the heraldic insignia of the Incas". In the 1917 edition of Flags of the World it is said that among the Incas "the heir apparent...had the right to display the royal rainbow standard in his military campaigns& #34;.

Crimson flag of Tupac Amaru I and II

Tupac Amaru I, the fourth and last Inca of Vilcabamba, used a crimson flag at the door of his home.

Tupa Amaro had two on. flags of tafetan carmesi at the door of the house he occupied [..]Huerto Vizcarra Héctor

During the 1780 revolution led by Tupac Amaru II, the crimson flag was also used, which included two snakes inside which came out of their mouths a rainbow, a heraldry similar to the pre-Hispanic Inca banners.

Confusion with the Flag of the city of Cusco (Peru)

The wiphala is often confused with a flag with seven horizontal stripes in the colors of the rainbow, used as the official emblem of the city of Cusco (Peru), and poorly associated with the Inca empire. However, it should be noted that while the wiphala is an emblem related to the peoples of Aymara origin, the Incas originated from the Quechua ethnic groups.

It has even been determined that this supposed "flag of the Incas" It does not have historical support, since its appearance is recent. Thus, it is known that in 1973, the engineer Raúl Montesinos Espejo, when commemorating the twenty-fifth anniversary of his radio station & # 34;radio Tahuantinsuyo & # 34; that operated in the city of Cusco, used this flag with the colors of the rainbow. Its use was so widespread in that city that in 1978, Gilberto Muñiz Caparó -mayor of the provincial municipality of Cusco- declared that flag as an emblem of the city.

Peruvian historiography has been emphatic in specifying that the concept of a flag did not exist in the Inca empire, and why it never had one. This has been stated by the historian and researcher of the Tahuantinsuyo ―the Inca Empire―, María Rostworowski (1915-2016), who when asked about this multicolored banner said:

I give you my life, the Incas didn't have that flag. That flag did not exist, no chronicler refers to it. [...] We'll wipe out the truthful things of nonsense. It is time to do a deslinde and rectify, because it is taking body one thing that is not historical. And history must be defended.Maria Rostworowski

In 2011, the Congress of the Republic of Peru ―quoting the National Academy of History of Peru― spoke out against this Tahuantinsuyo flag:

The official use of the so-called “Tahuantinsuyo Flag” is unequivocal and misuse. In the Andean pre-Hispanic world the concept of flag was not lived, which does not correspond to its historical context.National Academy of History of Peru

In current Andean customs

According to Andean customs and traditions, the wiphala is always raised in all social and cultural events, for example, in Aillu community meetings, in community marriages, when a child is born in the community, when a child's haircut is performed (Andean baptism), at burials, etc.

The wiphala is also waved at solemn festivals, at community ceremonies, at marka ('people') civic events, at wallunk'a ('swing'), in the competition games atipasina ('to win'), the historical dates, in the k'illpa (ceremonial days of cattle), in the transmission of command of the authorities in each period.

It is also used in dances and dances, such as in the Anata or Pujllay ('game') festival: in agricultural work with or without teams, through the ayni, the mink'a, the chuqu and the mit'a. It is even raised at the end of a work, a house construction and in all community work of the ayllu and marka.

Contenido relacionado

Slovakia

Ptolemy

Archaeological site of Atapuerca