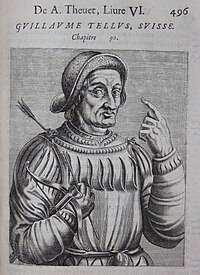

William Tell

Wilhelm Tell (Wilhelm Tell, in German) is a legendary character of Swiss independence (XIV). There is no contemporary documentary evidence to date of the existence of William Tell that can prove that he was a real person. His existence appears in a series of legendary tales from the 15th and 16th centuries that include high doses of fantasy and folkloric motifs. However, it is probable that some of the features and episodes attributed to it actually belonged to some unidentified fighter (or fighters) for Swiss independence at the beginning of the century XIV, which the popular imagination would later have endowed with legendary elements.[citation required]

The Legend

According to legend, Tell was an inhabitant of Bürglen (a town in the Swiss canton of Uri), a crossbowman, famous for his marksmanship, from the end of the century XIII and early XIV. At that time, the House of Habsburg had recently annexed some Swiss cantons in its attempt to achieve territorial contiguity between its Upper Rhine and Tyrolean possessions.

One day when William Tell, who until then had not carried out any political activity, was passing through the main square of Altdorf accompanied by his son, he refused to bow as a sign of respect before the hat installed in the square symbolizing the sovereign of the House of Habsburg.

Faced with such a show of rebellion against his legitimate master, the governor of Altdorf, Hermann Gessler, presented as an angry and bloodthirsty individual, arrested Tell. News of his fame as a crossbowman having reached his ears, he forced him to shoot his crossbow at a green apple[ citation needed] placed on the head of his own son, who was 100 paces away. If Tell was right, he would be cleared of any charges. If he didn't, he would be sentenced to death.

Tell tried in vain to get Gessler to change his punishment, so he inserted two arrows into his crossbow, took aim, and thanks to his skill as a crossbowman managed to hit the apple without hurting his son. When the governor asked him the reason for the second arrow, William Tell told him that it was aimed at the heart of the wicked governor in case the first had wounded his son.

Enraged by the response, he arrested him again and had him imprisoned in the castle of Küssnacht. On the way to the castle, across the Lake of the Four Cantons, a storm broke out during the voyage that almost capsized the ship. Untied by the guards so that he could take them ashore, Tell seized control of the boat and managed to bring it to shore, thus saving his life and that of the other occupants of the boat, including Tell himself. Gessler.

Hardly disembarked, William Tell fled, ambushing the Governor soon after and killing him with his second arrow. This fact would mark the beginning of the uprising of the Swiss cantons of Uri, Schwyz and Unterwalden against the Habsburgs, becoming a fundamental myth in Switzerland's fight for its independence.

The Story

It was not until more than a century and a half after the events carried out by William Tell that they began to be collected in chronicles and ballads transmitted orally. Around 1470 the first mentions appear in Swiss written texts and the existence of a drama in verse, in German, called Wilhem Tell, which was recast in 1545 by Jacob Ruof (1500-1558), is known. However, the classic version of the myth appeared in the Chronicon Helvetium by Egidio Tschudi, almost 200 years after the time when the events reported occurred. This chronicle dates the events carried out by William Tell in November 1307, and that of 1308 as that of the definitive liberation of Switzerland.

However, there is no contemporary evidence that Tell or Gessler existed. What's more, there are abundant legends that, with other characters and in other places, relate an archery feat similar to that of Tell. For example, the motif of the shot at the apple finds a very similar episode in the Danish Chronicle of Saxo Grammaticus (circa 1200), as well as in an old English ballad by William of Cloudeslee. Perhaps for this reason, in the 18th century a historiographical current arose that questioned the historical existence of the hero due to the lack of sources contemporary historical and the undeniable folkloric roots of some elements that adorn the legend.

In any case, the myth fits perfectly with the resistance movement born among the peasants of the canton of Uri from 1278, which confederated with those of Schwyz and Unterwalden, forming a Perpetual League (1291) in against the Habsburgs. This movement quickly turned into an open rebellion against the Habsburgs, which culminated in the victory of the troops of the three cantons over Leopold I, Duke of Austria at the Battle of Morgarten (1315). The three predominantly rural, German-speaking cantons formed the Swiss Confederation, the nucleus of present-day Switzerland.

Schiller and Rossini

Over the centuries, the figure of William Tell embodied the ideals of fighting for Swiss freedom and independence first, and later those of fatherly love and the fight for justice. Numerous authors, especially during Romanticism, found William Tell as his source of inspiration. Friedrich Schiller was based on the legend of William Tell to write a drama in five acts and in verse, belonging to the classical period of German literature: Wilhelm Tell (in German: Wilhelm Tell), in 1804.

Schiller's drama served as an inspiration to numerous later authors, such as the historical drama Guillermo Tell by Antonio Gil y Zárate. Later, Eugenio d'Ors also published in 1926 his work Guillermo Tell. Political tragedy, written in 1923 during a vacation in Tyrol, an original reworking of the legend of the Swiss hero.

For his part, Gioachino Rossini used the play, adapted into French by Victor Étienne and by Hippolyte Bis from Schiller's text, to compose the opera that bears the same name in 1829, which premiered in Paris. The overture of said opera is world-renowned and popular.

Other literary elaborations

In William Tell for School (Wilhelm Tell für die Schule), from 1971, Max Frisch presents a markedly different version of the character and his history. Here, he is no longer a hero of freedom, but a stubborn and stubborn peasant, determined to do something – shoot the crossbow – that nobody demands of him. The representative of imperial power appears as a man tormented by migraines, alpine winds and the misunderstanding of the behavior of the locals. The national myth is dismantled. The novel has the curious element that footnotes, with original quotes and documentary references, support the version presented by Frisch.

Contenido relacionado

Luca Giordano

Juan Perez Villamil

Juan Moreira