White blood cell

The leukocytes (from the Greek λευκός [leukós] 'white', and κύτος [kytos] 'bag', hence also called white blood cells) are a heterogeneous group of blood cells that carry out the immune response, thus intervening in the body's defense against foreign substances or infectious agents (antigens). They originate in the bone marrow and lymphatic tissue. Leukocytes are produced and derived from multipotent cells in the bone marrow, known as hematopoietic stem cells. White blood cells (leukocytes) are the only blood cells found throughout the body, including blood and lymphoid tissue.

There are five different types of leukocytes, divided into granulocytes and agranulocytes, and several of them (including monocytes and neutrophils) are phagocytic. These types are distinguished by their morphological and functional characteristics.

The number of leukocytes in the blood is often an indicator of disease. The normal white blood cell count ranges from 4 to 11 x 109/L, and is usually expressed as 4,000-11,000 white blood cells per microliter. They make up approximately 1% of the total blood volume of a healthy adult. An increase in the number of leukocytes above the upper limit is called leukocytosis, and a decrease below the lower limit is called leukopenia.

Etymology

Leukocytes, from the Greek λευκός [leukós] 'white', and κύτος [kytos] 'bag', are also called white blood cells. The term "white blood cell" derives from the appearance of a blood sample after it has been centrifuged. Leukocytes are found in the "buff," a thin, typically white layer of nucleated cells that lies between the red blood cells and the blood plasma. If there are large numbers of neutrophils in the blood sample, the buffy coat may appear green, because they produce a heme-containing enzyme called myeloperoxidase.

Features

Leukocytes (white blood cells) are mobile cells that are temporarily found in the blood, thus, they form the cellular fraction of the figurative elements of blood. They are the hematic representatives of the white series. Unlike erythrocytes (red blood cells), they do not contain pigments, which is why they are called white blood cells.

They are cells with a nucleus, mitochondria and other cellular organelles. They are able to move freely using pseudopods. Its size ranges from 8 to 20 μm (micrometers). Their life time varies from a few hours. These cells can leave the blood vessels through a mechanism called diapedesis (they prolong their cytoplasmic content), this allows them to move outside the blood vessel and have contact with the tissues inside the body. human.

Classification

All white blood cells are nucleated cells, but are otherwise distinct in form and function.

Leukocytes are divided into two major classes:

- Granulocytes (Neotrophils, Eosinophiles and Basophiles)

- Granulocytes, which lack specific granules, are mononuclear and have the largest kernel of granulocytes. It's the monocytes and lymphocytes.

By their lineage, white blood cells are divided into: myeloid (composed of granulocytes and monocytes) and lymphoid (T lymphocytes, B lymphocytes and natural killer cells (NK cells).

Also,

General information

Neutrophils

Neutrophils defend the body against viral, bacterial, or fungal infections. They are usually the first to respond to a microbial infection; their activity and death in large numbers form the pus. Neutrophils are commonly referred to as polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs), although, in the technical sense, PMN refers to all granulocytes (including neutrophils, eosinophils, and basophils). They have a multilobed nucleus that can resemble multiple nuclei, hence the name polymorphonuclear leukocyte. The cytoplasm may appear transparent due to the granules staining pale lilac. Neutrophils are responsible for phagocytosing bacteria and are present in large numbers in pus. These cells are unable to renew their lysosomes (used during the digestion of microbes) and die after having engulfed a few pathogens. Neutrophils are the most common cell type found in the early phases of acute inflammation. They make up 60 to 70% of the total leukocytes in the human blood. The half-life of a circulating neutrophil is approximately 5.4 days.

Eosinophils

Eosinophils primarily deal with parasitic infections. They are also the predominant inflammatory cells during an allergic reaction. The most important causes of eosinophilia include allergies such as: asthma, allergic rhinitis, and hives; as well as parasitic infections. In general, its nucleus is bi-lobed. The cytoplasm is filled with granules that, with eosin staining, assume a color characteristic orange.

Basophils

Basophils are mainly responsible for allergic responses, since they release histamine, causing vasodilation. Its nucleus is bi- or trilobed, but it is difficult to detect, as it is hidden by the large number of coarse granules, these granules are characteristically blue under H&E staining.

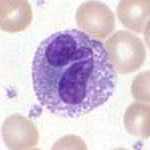

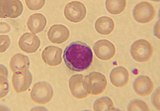

Lymphocytes

Lymphocytes are more common in the lymphatic system than in the bloodstream. They are distinguished by a strongly staining nucleus whose location may or may not be eccentric, and by having little cytoplasm. Lymphocytes include:

- Cells B, which produce antibodies capable of uniting, blocking, and promoting the destruction of pathogens as well as activating complement.

- Cells T:

- CD4+ cooperators: T cells express the CD4 co-receptor and are known as T CD4+ lymphocytes. These cells have T-cell receptors (TCRs) and CD4+ molecules that, together, recognize antigenic peptides presented in molecules of the major complex of histocompatibility (CMH) class-II by antigen-producing cells (CPA). Co-operative T cells produce cytokines and perform other functions that help coordinate an adequate immune response. In an HIV infection, the counting of these T cells is the primary index to identify the integrity of the individual's immune system.

- CD8+ cytotoxics: T cells that express the CD8 co-receptor and are known as T CD8+ lymphocytes. These cells bind to antigens presented in class-I CMH molecules in virus-infected cells or tumor cells. Almost all nucleated cells present CMH class-I. IgE.

- T γδ cells: have an alternative T cell receptor (different to the T αβ cell receptor found in conventional T CD4 and CD8 cells). They are more commonly found in tissues than in blood. The γδ T cells share characteristics with cooperative cells, cytotoxics and natural killer cells.

- Natural Killer Cells: They are cells capable of killing organism cells that do not present class-I HCM molecules, or that present stress markers such as MIC-A (MH)MHC class I polypeptide-related sequence A). The decrease in the expression of class-I CMH and the positive regulation of MIC-A can be performed when cells of the organism are infected by a virus or are cancerous.

Monocytes

Monocytes share the “vacuum cleaner” function (phagocytosis) with neutrophils, but they are more long-lived and also have an extra function: to present parts of pathogens to T lymphocytes so that they can be recognized again and eliminated. Monocytes leave the bloodstream (diapedesis) to become tissue macrophages that are responsible for removing remains of dead cells and attacking microorganisms. Unlike neutrophils, monocytes are capable of replacing their lysosomal content and their active life is believed to be much longer. Its nucleus is kidney-shaped and does not have granules and contains abundant cytoplasm. Once monocytes leave the bloodstream and enter some body tissue, they go through changes that allow them to phagocytosis (differentiate) and become macrophages.

Fixed leukocytes

Some leukocytes migrate to body tissues to reside there permanently and not in the bloodstream. Often these cells have specific names depending on what tissue they take up residence in; an example is the fixed liver macrophages, known as Kupffer cells. These cells continue to play an important role in the immune system.

- Histiocitos

- Dendritic cells (although these tend to migrate to local lymph nodes by ingesting antigens)

- Little children

- Microglia

Disorders

There are two main categories of disorders that involve white blood cells: proliferative disorders and leukopenias. In proliferative disorders there is an increase in the number of white blood cells; this increase is commonly reactive (for example, when due to infection), but it can be cancerous, too. In leukopenias there is a decrease in the number of leukocytes. Both disorders are quantitative. It has been observed that apoptotic processes in leukocytes could be related to the generation of free radicals in mitochondria from a change in intracellular calcium homeostasis. Qualitative disorders of white blood cells fall into a different category; in these the number of leukocytes is normal, but the cells do not function properly.

Leukopenias

A range of disorders can cause a decrease in white blood cells. The decreased cell type is usually the neutrophil. In this case, the decrease may be called neutropenia or granulocytopenia. In rarer cases, a reduction in the number of lymphocytes (called lymphocytopenia or lymphopenia) may be found.

Neutropenia

Neutropenia may be acquired or intrinsic. A decrease in neutrophil levels in a laboratory test may be due to decreased production or increased removal from the bloodstream of the cells themselves. Next, Several possible causes of neutropenia are listed (the list is not exhaustive).

- Medications - chemotherapy, sulfas or other antibiotics, phenotiazides, benzodiazepines, antithyroids, anticonvulsants, quinins, quinidines, indometacinas, procainamide, tiazides.

- Radiation.

- Toxins - alcohol, benzene.

- Intrinsic disorders - Fanconi syndrome, Kostmann syndrome, cyclic neutropenia, Chediak-Higashi.

- Immunodeficiency - collagen disorders, AIDS, rheumatoid arthritis.

- Blood cell dysfunction - megaloblastic anemia, myelodysplasia, medular failure, medular replacement, acute leukemia.

- Any serious infection.

- Miscellaneous - starvation, hyperesplenism.

Symptoms of neutropenia are associated with the underlying cause of decreased neutrophils. For example, drug-induced neutropenia is the most common cause of acquired neutropenia, so the patient may also present symptoms of drug overdose or toxicity. Treatment is also focused on managing the underlying cause of the neutropenia. One of the most serious consequences of neutropenia is that it increases the risk of acquiring infections.

Lymphocytopenia

Defined as a total lymphocyte count less than 1.0x109/L, the most commonly affected cells are CD4+ T cells. As in neutropenia, lymphocytopenia can be of acquired or intrinsic origin and there can be several causes (the list is not exhaustive).

- Inherited immunodeficiency - severe combined immunodeficiency, common variable immunodeficiency, ataxia-telangiectasia, Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome, immunodeficiency with short limb enanism, thymoma-associated immunodeficiency, nucleoside phosphorylase deficiency, genetic polymorphism.

- Bone marrow dysfunction - aplastic anemia.

- Infectious - viral diseases (AIDS, SARS, Nile encephalitis, hepatitis, herpes, others), bacterial (tuberculosis, typhoid fever, pneumonia, rickettsiosis, sepsis), parasitic (acute phase of malaria).

- Medications- chemotherapy.

- Radiation.

- Major surgery.

- Miscellaneous - extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (OMEC), kidney or bone marrow transplant, hemodialysis, kidney failure, severe burns, celiac disease, acute severe pancreatitis, enteropathy, vigorous exercise, carcinoma.

- Immunopathology - arthritis, systemic erythematous lupus, Sjögren syndrome, myasthenia gravis, systemic vasculitis, dermatomiositis, Wegener granulomatosis.

- Nutrition/diet - alcohol abuse, zinc deficiency.

Like neutropenia, the symptoms and treatment of lymphocytopenia are directed at the underlying cause of the cell count change.

Proliferative disorders

An increase in the number of white blood cells in the blood circulation is known as leukocytosis. This increase is commonly caused by inflammation. There are four main causes: cell overproduction in the bone marrow, increased release of cells stored in the bone marrow, decreased ability to adhere to the wall of blood vessels, decreased uptake by tissues. Leukocytosis can affect one or several cell lines and can be neutrophilic, eosinophilic, basophilic, monocytosis, or lymphocytes.

Neutrophilia

Neutrophilia is an increase in the total neutrophil count in the peripheral circulation. Normal values vary according to age. Neutrophilia can be caused by a direct disease of the blood cells (primary disease). It can also occur as a consequence of an underlying (secondary) pathology. Most cases of neutrophilia are secondary to inflammation.

Primary causes

- Conditions with functional neutrophils - hereditary neutrophilia, chronic idiopathic neutrophilia.

- Pelger-Huet anomaly.

- Down syndrome.

- Deficiency of leukocyte adherence.

- Family hive.

- Leukemia.

Secondary causes

- Infections.

- Chronic inflammation - especially juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, Still disease, Crohn's disease, ulcerative colitis, granulomatous infections (such as tuberculosis), and chronic hepatitis.

- Tabaquism.

- Stress - exercise, post-surgical.

- Induced by medicines - corticosteroids.

- Cancer - by growth factors secreted by the tumor or by the invasion of the bone marrow.

- Increased destruction in peripheral circulation can stimulate the bone marrow. This can occur in hemolytic anemia and idiopathic thrombocytopenic purple.

Eosinophilia

The normal eosinophilic count is considered less than 0.65×109/L. The count is higher in newborns and varies with age, time of day (it is lower in the morning and higher at night), exercise, environment, and exposure to allergens. Eosinophilia is never a normal finding in laboratory studies. Listed below are some of the causes of eosinophilia.

- Infections - bacterial, parasitic and mycotic

- Allergic reactions - asthma

- Autoimmune dermopathies - psoriasis

- Hemopathies - chronic myeloid leukemia

- Iatrogenic - streptomycin, sulfamides

- Idiopathic

- Family - Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome, hyper-IgE syndrome

Quantification and reference ranges

CBC with differential is a blood panel that includes total leukocyte count and various subclassifications such as total neutrophil count. Reference ranges for blood tests specify normal values in healthy individuals.

Contenido relacionado

Biological anthropology

Eremopoa

Quercus