Welsh language

Welsh Welsh (autoglottony: Cymraeg) is a language belonging to the Brythonic group of the Celtic language family. It is spoken in the country of Wales, where approximately 857,600 people (28% of the Welsh population) use it as their primary language, especially in the northern part of the country. Welsh is the official language along with English.

It is also spoken in various areas of southern Argentina, more specifically in the province of Chubut, where the largest Welsh community outside the British Isles lives (see Patagonian Welsh).

Historical, social and cultural aspects

The Welsh Language Today

Today there are schools and universities that teach in both Welsh and English. The Welsh Government and all public services are bilingual. There are several newspapers, magazines, and radio stations available in Welsh and also, since 1982, a Welsh-language television channel, called Sianel Pedwar Cymru or S4C.

Welsh was the main language of the country until King Edward I of England brought the country under the British Crown in the century. XIII. Although English is the dominant language today, Welsh is still important, and there is no risk of its disappearance in the short term.

It should be noted that Welsh was one of the favorite languages of the famous writer and philologist J. R. R. Tolkien (who used some of its sounds for his artistic languages, especially Sindarin). In his essay entitled "A Secret Vice" he listed Welsh among the "languages possessing characteristic and, each in its own way, beautiful word formation". In another essay, entitled "English and Welsh", he discussed the English word Welsh ('Welsh').

History

Like most languages, there are identifiable periods in the history of Welsh, although the boundaries between them are often very blurred.

Old Welsh

The oldest sources of a language identifiable as Welsh date back to about the VI century, and the language of this period is known as Primitive Welsh. Very little remains of this period. The next major period, somewhat better attested, is Old Welsh (Hen Gymraeg) (9th to 11th century); we preserve poetry from both Wales and Scotland in this form of the language. As the Germanic and Gaelic colonization of Britain progressed, Brittonic speakers in Wales found themselves separated from those in northern England, who spoke Cumbric, and from those in the south-west, who spoke the language that later became Cornish, and thus the languages separated. Both the Canu Aneirin and the Canu Taliesin belong to this period. It is not always possible to distinguish between Old Welsh texts and those of the old forms of the other Brittonic languages.

|

Middle Welsh

Middle Welsh (or Cymraeg Canol) is the label given to Welsh from the 12th to 14th centuries, a period from which we have more remains than from the previous one. This is the language of almost all of the surviving ancient manuscripts of the Mabinogion, though the tales themselves are much older. It is also the language of the extant manuscripts of Welsh Law. Middle Welsh is reasonably intelligible to a modern Welsh speaker with a bit of work.

Modern Welsh

Modern Welsh can be divided into two periods. The first, called Modern Initial Welsh, runs from the 14th century to about the end of the XVI, and was the language used by Dafydd ap Gwilym.

Modern Welsh Initial

This stage begins with the publication of William Morgan's translation of the Bible in 1587. Like the English translation, the King James Version proved to have a stabilizing effect on the language. Of course, there has been a lot of minor change in the language since then.

The 19th century

The language had a new rise in the 19th century with the publication of some of the first complete Welsh dictionaries. Earlier work by pioneering Welsh lexicographers, such as Daniel Silva Evans, ensured the correct documentation of the language, and modern dictionaries such as the Geiriadur Prifysgol Cymru (or University of Wales Dictionary), are direct descendants of these dictionaries.

However, the influx of English workers during the Industrial Revolution into Wales from about 1800 led to a substantial adulteration of the Welsh-speaking population of Wales. English immigrants rarely learned Welsh and their Welsh colleagues tended to speak English where there was some English, and bilingualism became almost complete. The legal status of Welsh was inferior to that of English, and thus English gradually began to prevail, except in the most rural areas, particularly north-west and central Wales. An important exception, however, were the Non-conformist churches, which were strongly associated with the Welsh language.

20th and 21st centuries

In the 20th century the number of Welsh speakers dropped to a point that predicted the extinction of the language in few generations. The first time the decennial census began to ask language questions was in 1891, at this time 54% of the population still spoke Welsh. The percentage decreased with each census, until reaching the lowest rate in 1981 (19%):

- 1891 = 1 700 000 inhabitants of which 898 914 speakers (54.4 %)

- 1901 = 2 015 000 inhabitants of which 929 824 speakers (46.15 %)

- 1911 = 2 205 000 inhabitants of which 977 336 speakers (43 %)

- 1921 = 2 660 000 inhabitants of which 929 183 speakers (37.2 %)

- 1931 = 2 158 000 inhabitants of which 794 144 speakers (36.8 %)

- 1951 = 2 597 000 inhabitants of which 737 548 speakers (28.4 %)

- 1961 = 2 644 000 inhabitants of which 652 000 speakers (26 %)

- 1971 = 2 700 000 inhabitants of which 542 402 speakers (20.84 %)

- 1981 = 2 807 000 inhabitants of which 503 549 speakers (19.1 %)

- 1991 = 2 914 000 inhabitants of which 572 102 speakers (19.63 %)

In 1991 the position was stable (19% as in 1981) and in the most recent census, 2001, it rose to 21% who could speak Welsh. The 2001 census also records that 20% could read Welsh, 18% could write it and 24% could understand it. Also, the highest percentage of Welsh speakers were among the youth, which bodes well for the future of Welsh. In 2001, 39% of 10-15 year olds could speak, read and write Welsh (many learning it at school), compared to 25% of 16-19 year olds. However, the percentage of Welsh speakers in areas where it is spoken by the majority is still on the decline.

As the influence of Welsh nationalism increased, the language began to receive government support and aid, all in addition to the establishment of Welsh-language broadcasting. It found a mass audience that was concerned about the stagnation of the language.

Possibly the most important recent development is that at the end of the XX century the study of Welsh was made compulsory for all pupils aged 16 and under, and this strengthened the language of Welsh-speaking areas, reintroducing at least a basic knowledge of Welsh to areas that had become almost entirely Anglophone. The decline in the percentage of Welsh people who can speak Welsh has halted and there are also signs of a modest recovery. Yet despite Welsh being the everyday language in some parts of the country, English is understood by everyone.

Spelling

Welsh is written in a version of the Latin alphabet consisting of 28 letters, eight of which are digraphs treated as single letters for context:

- a, b, c, ch, d, dd, e, f, ff, g, ng, h, i, l, ll, m, n, o, p, ph, rh, s, t, th, u, w, y

The letter j, although not originally used to write Welsh, was borrowed from the English alphabet and is used in some loanwords.

The most common diacritic is the circumflex, which is used in some cases to mark a long vowel.

Linguistic description

Phonology

Welsh has the following consonantal phonemes:

Bilabial Labio-dental Labio-velar Dental Alveolar Alveolar

sidePost-alveolar Palatal Velar Uvular Gloss Occlusive p d k g Africada (t ab) Nasal (m)) m (n)) n (GRUNTING) Fridge f θ ð s (z) MIN χ h vibrant r r Approximately w l j

/z/ only appears in unassimilated loanwords. /tʃ/ and /dʒ/ appears especially in loanwords, but also in some dialects as an evolution of /tj/ and /dj/; voiceless nasals /m̥/, /n̥/, /ŋ̊/ only appear as a consequence of nose mutation.

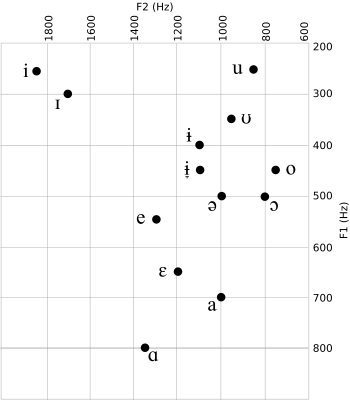

For the vowels we have the following vowel inventory:

Monoptongos Subsequential Central Previous Closed i ː u Almost closed . ♫ Semicrated e ♫ o Semiabierta ‐ Open a a

The vowels /ɨ̞/ and /ɨː/ only appear in northern dialects; in the south they are replaced by /ɪ/ and /iː/ respectively. In southern dialects, the contrast between long and short vowels is found only in the stressed syllable; in northern dialects, the contrast is only found in stressed final syllables (including monosyllables).

The vowel /ə/ does not appear in a word-final syllable (except in a few monosyllables).

Diptongos The second component

laterThe second component

is centralThe second component

is previousThe first component is closed ¢Ü ,u The first component is medium ,i ,,, 국 The first component is open ai a,, a au

Diphthongs containing /ɨ/ only occur in northern dialects; in southern dialects /ʊɨ/ is replaced by /ʊi/, /ɨu, əɨ, ɔɨ/ converge in /ɪu, əi, ɔi/, and /aɨ, aːɨ/ converge in /ai/ .

The stress in polysyllables usually appears on the penultimate syllable, very rarely on the last. Stress placement means that related (or plural) words and concepts can sound quite different when syllables are added to the end of a word and the stress moves accordingly, e.g.:

- ysgrif — /^^^sgriv/ — an article or essay.

- ysgrifen — /^s^griven/ — writing.

- ysgrifennydd — /^sgrið/ — a secretary.

- ysgrifenyddes — /^sgrive^nðes/ — a secretary.

(Note also that adding a syllable to ysgrifennydd to form ysgrifenyddes changes the pronunciation of the second "y". This is because because the pronunciation of the "y" depends on whether it is on the final syllable or not).

Morphology

The morphology of Welsh has much in common with the two other modern British languages, such as the use of initial consonant mutations (four are used in Welsh), and the use of so-called "conjugated prepositions" (prepositions fused with personal pronouns). Nouns can be masculine or feminine and have no declension. In Welsh there is a whole variety of endings that express the plural and two to indicate the singular of some nouns. In colloquial Welsh the verb conjugation is indicated mainly through the use of auxiliary verbs but with the conjugation of the verb itself. In literary Welsh, on the other hand, the proper verb conjugation is usual.

Other features of Welsh grammar

Possessives as object pronouns

In Welsh 'I like Rhodri' is Dw i'n hoffi Rhodri ("I am going to like [of] Rhodri"), but 'He I like' is Dw i'n ei' hoffi fe —literally, "I am in your like him"; I like you' is Dw i'n dy hoffi di ("I am in your to please you"), etc.

The use of auxiliary verbs

Colloquial Welsh tends very frequently to use auxiliary verbs. In the present, all verbs can be formed with the auxiliary bod 'to be'; thus, dw i'n mynd is literally "I am going," but simply means 'I am going'.

In the past and future, there are conjugated forms of all verbs (which are invariably used in written language), but today in speech it is much more common to use the verbal noun (berfenw) together with the conjugated form of gwneud 'do'; like this, 'I was' it can be mi es i or mi wnes i fynd and 'I will go' it can be my a' i or mi wna i fynd. There is also a future form with the auxiliary bod, giving bydda i'n mynd (more correctly translated as 'I will be going') and an imperfect (a past continuous/habitual tense) also using bod, with roeddwn i'n mynd meaning 'I used to go/was going'.

The affirmation

My or fe are frequently placed before conjugated verbs to indicate that they are declarative. In the present and imperfect of the verb bod 'to be', yr is used. My is more restricted to colloquial North Welsh, while fe predominates in the south and in the formal or literary register. Such a feature of enunciation is, if anything, much less common in high registers.

Numerals and counting system

The traditional counting system used by the Welsh language is vigesimal, i.e. based on twenties, as in the French numerals from 60 to 99, where the numbers from 11 to 14 are "x over ten", from 16 to 19 are "x over fifteen" (despite 18 being normally "two nines"); numbers 21 through 39 are "1–19 over twenty", 40 is "two score", 60 is "three score," etc.

There is also a system of decimal reckoning, popular with the youth, but common in South Wales, and which seems to be most widely used in Patagonian Welsh, where the numbers are "x ten and". For example, 35 in this system is tri deg pump ('three ten five') while in vigesimal it is pymtheg ar hugain (fifteen [–en reality "five-ten"]– out of twenty).

Another source of complication is that while there is only one word for "a" (un), there are different forms for the masculine and feminine in the numbers "two" (dau and dwy), "three" (tri and tair) and "four" (pedwar and pedair), which must agree in gender with the noun, although this rule is less strictly observed with the decimal reckoning system.

| Number | Vigesimal system | Decimal system |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | One | |

| 2 | dau (m), dwy (f) | |

| 3 | tri (m), tair (f) | |

| 4 | pedwar (m), pedair (f) | |

| 5 | pump | |

| 6 | chwech | |

| 7 | saith | |

| 8 | wyth | |

| 9 | naw | |

| 10 | deg | |

| 11 | ar ddeg | a deg. |

| 12 | deuddeg | a deg dau |

| 13 | tri/tair ar ddeg | a deg tri |

| 14 | pedwar/pedair ar ddeg | a deg pedwar |

| 15 | pymtheg | a deg pump |

| 16 | ar bymtheg | a deg chwech |

| 17 | dau/dwy ar bymtheg | a deg saith |

| 18 | deunaw ("two nines") | a deg wyth |

| 19 | pedwar/pedair ar bymtheg | a deg naw |

| 20 | ugain | dau ddeg |

| 21 | ar hugain | dau ddeg |

| 22 | dau/dwy ar hugain | dau ddeg dau |

| 23 | tri/tair ar hugain | dau ddeg tri |

| 24 | pedwar/pedair ar hugain | dau ddeg pedwar |

| 25 | pump ar hugain | dau ddeg pump |

| 26 | chwech ar hugain | dau ddeg chwech |

| 27 | saith ar hugain | dau ddeg saith |

| 28 | wyth ar hugain | dau ddeg wyth |

| 29 | naw ar hugain | dau ddeg naw |

| 30 | deg ar hugain | tri deg |

| 31 | ar ddeg ar hugain | Tri deg a |

| 32 | deuddeg ar hugain | tri deg dau |

| etc. | ||

| 40 | deugain ("two twenties") | pedwar deg |

| 41 | deugain ac | pedwar deg |

| 50 | hanner cant ("half hundred") | pump |

| 51 | hanner cant ac | pum deg |

| 60 | trigain | chwe deg |

| 61 | trigain ac | chwe deg un |

| 62 | chwe deg dau | trigain a dau |

| 63 | chwe deg tri | trigain a thri |

| 70 | deg a thrigain | saith deg |

| 71 | ar ddeg a thrigain | saith deg a |

| 80 | pedwar ugain | wyth deg |

| 81 | pedwar ugain ac | wyth deg a |

| 90 | deg a phedwar ugain | naw deg |

| 91 | ar ddeg a phedwar ugain | naw deg |

| 100 | cant | |

| 200 | dau gant | |

| 300 | tri black | |

| 400 | pedwar cant | |

| 500 | pum cant | |

| 600 | chwe black | |

| 1000 | a thousand | |

| 2000 | dwy fil | |

| 1 000 | miliwn | |

| 1 000 000 000 | biliwn | |

Notes:

- The words deg (ten) deuddeg (doce) and pymtheg (quince) often become deng, deuddeng and pymtheng respectively when they go before a word that begins by "m", e.g. deng munud (ten minutes) deuddeng milltir (twelve miles) pymtheng mlynedd (perhaps years).

- Numbers pump (five) chwech (six) and cant (cien) lose the final consonant when they go immediately before a noun, e.g. pum potel (five bottles) can punt (ten pounds) chwe llwy (six spoons),

- High numbers tend to use the decimal system, e.g. 1.965 thousand, naw cant chwe deg pump. An exception to this rule is to refer to the years, where after the number of the thousand the individual figures are said, e.g. 1965 thousand naw chwe(ch) pump (Like nine six five). This system has apparently disappeared since 2000, e.g. 2005 is dwy fil a phump (two thousand and five).

- Number miliwn ('million') is feminine, and biliwn ('billion') is male. This should be known because in certain circumstances both forms may mutate in filiwn. So 'two million' is dwy filiwn (dwy is female), and 'two billion is dau filiwn (dau is male).

Sample Text and Vocabulary

Gospel according to John chapter I 1-8

- Yn and dechreuad yr oedd and Gair, a'r gair oedd gyda Duw, a Duw oedd and Gair.

- Hwn oedd yn and dechreuad gyda Duw.

- Trwyddo ef and gwnaethpwyd pob peth; ac hebddo ef na wnaethpwyd dim a'r a wnaethpwyd.

- Ynddo ef yr oedd bywyd; a'r bywyd oedd oleuni dynion.

- A'r goleuni sydd yn llewyrchu yn and tywyllwch; a'r tywyllwch nid oedd yn ei amgyffred.

- Yr ydoedd gwr wedi ei anfon oddi wrth Dduw, a'i enw Ioan.

- Hwn a ddaeth yn dystiolaeth, fel and tystiolaethai am and Goleuni, fel and credai pawb trwyddo ef.

- Nid efe oedd and Goleuni, eithr efe a anfonasid fel and tystiolaethai am and Goleuni.

- Hi. - Helo.

- How are you? - Shw mae?

- What's your name? - Beth yw dy enw di?

- Who are you? - Pwy ydych chi?

- How are you? - Sut ydych/dach chi?

- Thank you very good. And you? - Da iawn diolch. A thi?

- My name is Henry. - Fy enw i yw Henry.

- I'm Marina. - Marina ydw i.

- I got a car. - Mae gen i gar

- You have a house. - Mae gennyt dj.

- There's a mine. - Mae chwarel.

- It's huge. - Mae'n enfawr.

- He's one of my friends. - Ef yw un o'm ffrindiau.

- Mi/mis - Fy

- Your/you - Dy

- Yours - Hey.

- Ours - ein.

- Your - eich.

- Yours - Whoa.

- The river - Yr afon

- The estuary - Yr aber

- The store - And siop

- The pharmacy - And fferyllfa

- The bridge - And bont

- The coast - Yr arfordir

- The city - And ddinas

- Wet zone - Ardal wlyb

- Seismic zone - Ardal seismig

- I am. - Rydw i/Dw i

- You are. - Rwyt ti/Wyt ti

- That's it. - Mae

- We are - 'Dyn ni/Dan ni

- Sois... Ydych chi/Dach chi

- They are. - Maent/Maen

Contenido relacionado

Maltese language

Part of speech

Ladino