Weimar Republic

The Weimar Republic (German: Weimarer Republik) was the political regime and, by extension, the period of German history comprised between 1918 and 1933, after the country's defeat in World War I. The name Weimar Republic is a term applied by later historiography, since the country retained its name of Deutsches Reich ("German Empire »). The name comes from the German city of Weimar, where the Constituent National Assembly met and the new constitution was proclaimed, which was approved on July 31 and entered into force on August 11, 1919.

This period, although democratic, was characterized by great political and social instability, in which there were military and right-wing coups, revolutionary attempts by the left and strong economic crises. All this combination led to the rise of Adolf Hitler and the National Socialist Party. On March 5, 1933, the Nazis obtained a majority in the Reichstag elections, with which they were able to approve the Enabling Law on March 23, which, together with the Reichstag Fire Decree of February 28 and by allowing the approval of laws without the participation of Parliament, it is considered to have spelled the end of the Weimar Republic. Although the Constitution of August 14, 1919 was not formally repealed until the end of World War II in 1945, the triumph of Adolf Hitler and the reforms carried out by the National Socialists (Gleichschaltung) invalidated long before, establishing the so-called Third Reich.

Establishment of the Republic (1918-1919)

The November Revolution

In the closing months of World War I, Germany was on the brink of military and economic collapse. Before the final offensive of the Allies, on August 14, 1918, the German High Command met at its headquarters in Spa and recognized the futility of continuing the war. He did not want the allies to be able to discover the real state of his forces, let alone find it impossible to stop their advance. They hoped to save the army, not the regime, by negotiating, when it was still a hundred kilometers from Paris. On September 27 Paul von Hindenburg and Erich Ludendorff informed the imperial government and called for an immediate armistice on the basis of Wilson's famous 14 points. Politicians immediately understood that the war was lost and that the military had tried to cover it up. Within days a new parliamentary government was organized, and the newly appointed chancellor, Prince Maximilian of Baden, a well-known liberal and pacifist, proceeded to negotiate peace. Woodrow Wilson, with his back to his allies, demanded above all the transformation of the political and military institutions of the Reich. The army opposed it, and Ludendorff resigned in a resounding fashion, fueling the myth of "betrayal" by civilians to win over public opinion. For their part, the socialists in power awaited the abdication of Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany to seize control, although their leaders made desperate efforts to preserve the imperial form of the state. The situation was then suddenly interrupted by the events in Kiel.

While the exhausted and hopeless troops and population awaited the armistice, in Kiel, the Marine High Command (Marineleitung) under the command of Admiral Reinhard Scheer wanted to cross fire for the last Once with the British Royal Navy, he announced to the High Seas Fleet (Hochseeflotte) of the Imperial Navy that he was to set sail. Preparations to put to sea promptly caused a mutiny in Wilhelmshaven, where the German fleet had dropped anchor awaiting attack. The mutinous sailors refused to engage in battle for nothing more than honor. The High Command of the Navy decided to call off the attack and ordered a return to Kiel to try the mutineers in court martial. The remaining sailors wanted to avoid the process, because the mutineers had also acted in their interest. A union delegation requested his release, but was rejected by the High Command of the Navy. The following day, the union house was closed, and on November 3 the protest rallies were repressed with clean shots, causing the death of nine people. When a sailor returned fire and killed an officer, the demonstration turned into a general revolt.

On the morning of November 4, the sailors elected a soldiers' council, disarmed their officers, occupied the ships, freed the mutinous prisoners, and seized control of the Kiel naval base. The sailors were joined by civilian workers, especially metallurgists. After merging into a council of workers and soldiers, similar to a soviet, they stormed the barracks and seized the city to the sound of La Internacional, demanding an improvement in food, the abandonment of the fleet offensive project, the liberation of the detainees, universal suffrage and the abdication of the emperor. In the afternoon they were joined by soldiers from the army that the local command had brought in to put down the revolt. Kiel was thus firmly in the hands of 40,000 insurgent sailors, soldiers and workers. On the night of November 4, Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) deputy Gustav Noske came to Kiel on behalf of the SPD leadership and the new Reich government, to control the revolt and prevent a revolution. The city council believed that it was on the side of the new government and had its support. For this he appointed Noske "governor" that same night and he effectively ended the revolution in Kiel the next day.

Meanwhile, the Kiel mutiny had ignited revolution in the rest of Germany. The barracks rose up against the officers and the commanders were relieved of their duties. Solidarity strikes spread the insurrection from the coast to the cities, and from the cities to the interior. In Brunswick the newly arrived sailors joined the workers, forced the Grand Duke to abdicate and proclaimed the Brunswick Socialist Republic. The process of strike, riot, assault on prisons, and proclamation of workers' and soldiers' councils was repeated in all the cities of the country. But unlike the Russian soviets, these Ratebewegungen emanated more from the will of the soldiers than from the will of the workers. On November 6, knowing that William II would not be able to keep his throne, Maximilian von Baden urged him to abdicate at the Kronprinz, thus saving the Monarchy, to no avail. In Munich, on November 7, King Ludwig III of Bavaria fled, and the following day a council of soldiers, workers and peasants led by Kurt Eisner, an independent socialist, was formed, which proclaimed the Republic of Bavaria. On November 9 the revolution reached Berlin, and in a few hours the Reich was coming to an end when Chancellor Maximilian von Baden announced the abdication of the Kaiser and the Kronprinz and appointed his successor to the social democrat Friedrich Ebert. Without the slightest resistance, the ruling princes of the other German states abdicated and that same day two republics were proclaimed: Philipp Scheidemann, former imperial minister, proclaimed the Republic from the Reichstag, and two hours later Karl Liebknecht (leader with Rosa Luxemburg of the Spartacus League) appeared at the Royal Palace in Berlin and announced the Free and Socialist German Republic.

Political parties

The seizure of power by the masses had as an immediate consequence the fact that Germany handed over political power to socialism. In November 1918 the great majority of the country was sincerely ready to support a democratic government. Since the Social Democrats were considered democrats, and were the largest parliamentary party, there was almost complete unanimity in entrusting them with the direction and formation of the future system of government. However, the Social Democrats had split; Relevant Marxists rejected democracy and declared themselves in favor of the dictatorship of the proletariat. Three socialist currents thus appeared:

- Social-Democracy (SPD): with 35% of the Reichstag seats in the 1912 elections, she was the main representative of German society. He also enjoyed an extraordinary preaching among the popular classes for their antiquity, organization and number of sharpened. Obedients of the imperial regime, with the fall of this was intended to replace militarist and feudal Germany with a parliamentary democracy, restore civic liberties and the rights of man (subpended in the course of the war) and increase the program of measures of the pre-existing sozialpolitik (social welfare policy). The Social Democrats completely rejected the Bolshevik model of armed revolution and dictatorship of the proletariat, and enhanced collaboration with other political forces to democratize institutions.

- The independent socialists (USPD) appeared in 1917 without a clear programmatic formulation, as opposed to the continuism that the SPD made of the imperial government in the war. Partisaries of the restoration of socialist unity defended both parliamentarism and revolutionary councils, in the belief that the latter should supervise the former. They shared the SPD's desire to enhance social policy, and advocated the socialization of the economy through the partial nationalization of certain economic sectors, as part of finance and heavy industry, but maintaining internal and external trade in private hands. They rejected the collectivization of land, but proposed a redistribution for small farmers. They opposed the bourgeois authorities and rejected the bureaucratism of institutions and trade unions, against the SPD.

- The Spartaquest League: initially part of the USPD, became a revolutionary party. They rejected social-democratic revisionism and considered the events of November a stage in the final goal of the socialist revolution and the dictatorship of the proletariat. They considered the Bolshevik revolution an example to follow, with certain adjustments and the correction of Lenin's errors regarding the maintenance of individual liberties. They believed that the proletarians should take control of the bourgeois institutions and supplant them with their own representative bodies, exclusively formed by members of their party, to achieve a true democracy, without terror and repression coming into principle in their ends. Its 24 proposals for the protection of the revolution included the disarmament of the army and the police, the suppression of the parliamentary regime and the socialization of the economy through the confiscation of large fortunes, banks, properties and factories, transports and the media and the directsm of production. Regardless of all this, seen with perspective, their efforts were doomed to the failure given their limited number and to the negative effect that the Russian Revolution had produced in public opinion, assimilating the Soviet horrors to the Spartacists.

The social democrats allied themselves with the independents and found a place in the organizations of the November Revolution, articulating a bicephaly between the political representatives and those of the popular councils. On November 10, six People's Commissars (3 Social Democrats and 3 Independents) formed the Provisional Government. The following day they signed the Armistice of Compiégne, based on Wilson's 14 points, and on the 12th they promulgated a program of economic political action with a view to national reconstruction. A Provisional Executive Council completely dominated by the Social Democrats was created as the link between the provisional government and the councils. This Council does not hesitate to ratify the government's actions, and turns a deaf ear to the Spartacists. The Councils had lost their usefulness for a government whose main concern was precisely to avoid a Revolution, limiting itself to the peaceful change of the chancellor and the form of the State. Finally, the Pan-German Congress of Councils, meeting in Berlin from December 16 to 20, overwhelmingly supported the Social Democratic theses, for which it was dissolved and entrusted the fate of the Republic to the calling of elections for a National Constituent Assembly. With this, the Revolution ended before it began, and the popular classes were marginalized from politics. This voluntary relinquishment of power caused the astonishment and desperate action of the Spartacist League, rejected by the majority of the population, which had not obtained more than 10 delegates out of a total of 489 in the aforementioned Congress.

To consolidate itself, the newborn Republic reached an agreement between unions and employers (November 15), thus reassuring the bourgeoisie. The workers obtained guarantees such as the eight-hour day without a decrease in wages, the resignation of the employers to take action against the unions and the regulation of work with collective agreements. For their part, the industrialists averted the danger of the revolution and the socialization of the economy, defended by the Spartacists. Similarly, an agreement was reached with the monarchist army to create a government of order and combat the Bolshevik threat. For its part, the old imperial political class had adapted to -although generally not accepted- the new legality in the form of new right-wing parties, the so-called populares: the anti-republican and pan-Germanist conservatives in the Deutsche Nationalen Volkspartei (DNVP), while the Liberals split into the right-wing Deutsche Volkspartei (DVP) and the left-wing Deutsche Demokratische Partei (DDP). Only the Catholic and centrist Zentrumspartei (ZP) retained its previous name. Non-liberal right-wing parties were themselves influenced by perceptions of the so-called Conservative Revolutionary Movement.

The Spartacist Uprising (Der Spartakusaufstand)

Between the decision to transfer power to a Constituent Assembly, and the date of its actual application, January 19, the last phase of the Novemberrevolution took place. The independent socialists were soon sidelined precisely because of their conciliatory character, labeled traitors by the Spartacists and insincere allies by the social democrats. Allied with the army, the Social Democrats turned to more moderate positions and proceeded to dissolve the councils, restore command authority to officers, and requisition weapons held by civilians.

For their part, the Spartacists became increasingly radicalized, hoping to stop the counterrevolution. Eager to emphasize their preference for the Soviet model, on December 30, 1918 the Spartacists founded the KPD (Kommunistische Partei Deutschlands or German Communist Party), renouncing to participate in the January 19 elections and marking themselves revolutionary goals. The very idea of democracy became suspect. For many Germans the term was since then synonymous with fraud, a fact that would later give wings to Nazism.

Nationalists quickly caught on to the change in mentality and seized on the occasion. If a few weeks before they had felt desperate, now they knew how to return to power. They coined the legend of the "stab in the back," which restored their self-confidence and popular support. But his first objective was to prevent the establishment of a socialist state. To do this, an essentially undemocratic party like the DVNP presented to the electorate, for purely tactical reasons, a liberal and democratic program. Supporting the parliamentary regime in the short term, they intended to do away with it later.

For their part, the communists hoped to seize power by force, with or without help from the Bolsheviks in Russia. At Christmas 1918, a conflict broke out in Berlin between the provisional government and a bellicose communist troop, the "Volksmarinedivision" (People's Sailors' Division), which opposed the current government and entrenched itself in the Royal Palace in Berlin, coming to besiege Chancellor Friedrich Ebert in his office. Panicking, he called for help from a dismounted cavalry company of the old Royal Guard, commanded by an aristocratic general, which was on the outskirts of the capital awaiting disbandment. There was a fight favorable to the Guard, but the government ordered them to withdraw, since it distrusted them and did not want to fight against their own comrades. This skirmish convinced the independent socialists that it was impossible to avoid the triumph of communism, and in order not to lose popularity or arrive too late to participate in the imminent communist government, they withdrew their three commissars, leaving the SPD in exclusive charge. of the government, which increased their inclination towards moderate positions.

On January 4, 1919, the independent socialist Emil Eichhorn resigned as police chief, and this served as a pretext for the general strike, which on the 6th paralyzed Berlin and became an attempted insurrection; communists and independent socialists began the battle in the streets of Berlin and came to dominate the center of the capital. The USPD and KPD formed a weak and indecisive "ruling committee" about which course to take, and the movement spread to Bavaria, Bremen, Hamburg, Saxony, Magdeburg, and Saarland. The Spartacist leader Karl Liebknecht called for the overthrow of the Ebert government as soon as possible, against the opinion of Rosa Luxemburg (who still feared the strength of the right-wing elements that dominated the army) and, after the failure of the talks with the government, Liebknecht called the workers to take up arms and rise up.

The situation was desperate for the Ebert government when unexpected help appeared, when defense minister Gustav Noske decided to use the Freikorps (anti-republican paramilitary organizations, made up of former soldiers) to put an end to with the uprising. Between January 8 and 13 the Freikorps, well armed and better disciplined, easily recaptured the capital and murdered hundreds of leftist revolutionaries, including Liebknecht and Luxemburg. Curiously, among those who contributed huge sums of money to pay for the maintenance and transportation of the Freikorps was, among others, the left-liberal Walther Rathenau, later assassinated by them.

On the other hand, around this time (January 5, 1919) the German Workers Party was formed. Founded by Anton Drexler and Karl Harrer, it was initially a small party with contradictory ideas, until a war veteran named Adolf Hitler joined them in October 1919, taking over the leadership of the movement a little later until it became the Party. German National Socialist Workers.

The government's victory did not end the civil war, which still lasted several months in several provinces, with the removal of revolutionary islets in Bremen and the Ruhr. Nevertheless, the elections, the sessions of the constituent assembly and the proclamation of the Weimar Constitution could be held. There was a participation of 83.0% in the elections and the SPD obtained 37.9% of the votes and 165 seats, followed by the ZP (19.7% and 91 seats), the DDP (18.6% and 75 and esc.), the DVNP (10.3% and 44 sec.), the USPD (7.8% and 33 sec.) and the liberal DVP of Gustav Stresemann (4.4% and 19 seats). Despite obtaining a majority, the SPD was forced to agree with the center parties in order to govern. Thus, the so-called Weimar Coalition was formed, and Ebert was elected President of the Republic, by 277 votes in favor, 51 against, and 51 abstentions; Scheidemann was appointed head of government.

Paradoxically, the republican regime owed its existence to the paramilitary and anti-democratic forces of a nationalist right, radically opposed to parliamentarism, which was waiting for the opportunity to put an end to it. Non-communist Marxists severely reproached Ebert, Noske and other Social Democratic leaders for collaborating with the nationalists who had defeated the Spartacists. Indeed, through this strategy, the republican regime had avoided the establishment of a communist state that copied the Bolshevik model, however, the political cost was that the social democrats were publicly discredited.

The Social Democrats managed to form a government in Prussia and other länder only thanks to the support of the nationalists, the imperial army turned Reichswehr and the Freikorps i>, and from then on they were at the mercy of the right, whose power went far beyond what was merely parliamentary. The two great factions in contention, ultranationalists and communists, considered the Republic solely as a battlefield in their struggle for power. But in this extra-parliamentary struggle, while the former could act freely and knew from experience the springs of power, the latter did not, and this determined the ultranationalist victory. Between those two "dictatorial" parties there was no third party that defended capitalism and representative democracy. The only alternative to belligerent nationalism and socialism would have been liberalism, but the only party that could have changed the situation, Gustav Stresemann's monarchist and free-trade DVP, lacked the necessary social base and parliamentary representation. Neither the Social Democrats nor the Catholic center were suited to adopt representative democracy, which they described as plutocratic, and republicanism, branded as bourgeois, and they were not willing to renounce statism and sozialpolitik. After the experience of the war, the masses perceived that the autarky advocated by all of them was fatal for the economy, and that the only ones who had an idea of how to deal with it were the extreme right-wing nationalist parties (even if it was with the expansionist doctrine of lebensraum).).

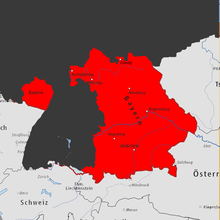

The Bavarian Crisis

Since the meeting of the National Assembly in Weimar, Kurt Eisner had become the champion of the Länder against centralism in Berlin. His assassination on February 21 at the hands of a right-wing extremist (Count Arco-Valley) had great repercussions in Munich, where councilism still maintained its lost validity in Berlin. The situation quickly degenerated. The conservative Bavarian diet (Landtag) was completely marginalized by the Councils, which quickly radicalized, finally proclaiming, at the behest of Lenin's Russia and Béla Kun's Hungary, a Council Republic Bávara (April 7) with a clear anarchist inspiration. It rejected parliamentarism and tried to undertake the social revolution, but it was a complete failure. The Councils had lost all contact with the masses and social reality, and not even the new communist party supported their political line. It was the communists themselves who ended up rising up against the Republic of Bavaria in an attempt to save it, but it was soon organized the counterrevolution, led by the prime minister of the SPD, Hoffmann, who totally crushed the Revolution in two weeks (end of April-beginning of May 1919). The executions numbered in the hundreds, and from this moment on, Munich became the conservative, counterrevolutionary and anti-republican capital, allowing for many years the activities of the most exalted nationalists, such as Hitler and Ludendorff. When, yielding to Allied pressure, the government promulgated a law on the surrender of arms held by individuals, Bavaria resisted, refusing to disarm the counterrevolutionary militias, which provoked a crisis that lasted from August 1920 until 1921.

The Weimar Constitution

The Constitution, made up of 181 articles, was discussed between February and July, and was approved on July 31, 1919 by 262 votes in favor and 72 against (independent, liberal, and national socialists). The spirit of concord and mutual understanding overflowed on all four sides, and as such, the lack of definition and ambiguity. In Weimar, a new State was not established, but rather the Deutsche Reich (which even retained its name) was simply given a new form, the republican one. The people experienced the disappointment of the imposition of a Constitution in which they did not participate. He came to the idea that, ultimately, the Republic had supplanted the Empire without their principles of government differing. Notwithstanding which, Weimar was an advanced democratic republic. At the head of this federal and parliamentary State, a president elected by direct suffrage for a seven-year term was placed, endowed with strong authority and the right to dissolve Parliament, which recalls the powers of the former emperor and the limitations of parliamentarism bismarckian. Parliament was made up of an elective chamber, the Reichstag, and a territorial one, the Reichsrat. The chancellor, appointed by the president, assumed executive power. The new Constitution enshrined proportional suffrage (and the consequent fragmentation of the chambers), the emergency powers available to the president and the use of a plebiscite: on the one hand, the possibility for the president to submit a legislative text to the people, in case of disagreement with the Reichstag; on the other hand, the possibility for 1/10 of the voters to formulate a bill to submit to the people, or the power to defer the promulgation of a law if 1/3 of the Reichstag and 1/20 of the voters requested it.

Unity triumphed over local particularisms (Reichsrechtbricht Landrecht), but as in Bismarck's time, also in the Weimar Republic the main powers of civil administration were exercised by governments of the States that formed it instead of the government of the Reich. Prussia was the largest and richest state, the one with the most numerous population, and its overwhelming predominance in the Reichsrat: to govern Prussia was to govern the Reich, without having to take into account the other states.

Similarly, the adjective «social» appeared for the first time in the Weimar Constitution, proclaiming that the State seeks, in addition to democracy, an element of the liberal constitutions written until then, social justice.

Sometimes the deficiencies of this Constitution have been blamed for the errors of the Republic and its fall. However, different authors point out that no democratic Constitution could have dealt with the lack of popular support for the regime, which led to its final crisis and the rise of the Nazis. They add that the Weimarian constitution worked remarkably well during the Stresemann government, between 1924 and 1929.

An aborted socialization

The social democrats had placed at the head of their programs the socialization of the means of production (Vergesellschaftung). The nationalizations and the «socialism» applied during the war (Zwangswirtschaft or centralized planning) had, however, been very beneficial for some capitalist businessmen allied with the Reich government and very detrimental to production and interests. of the workers, due to which they were extremely unpopular. The Social Democrats approached the issue with demagogy: they attacked war socialism as the worst kind of capitalist abuse and exploitation, but were unable to establish any real differences between their projects and the Zwangswirtschaft, also rejecting the instruments of nationalization, now as revolutionaries, now as bourgeois. According to the famous liberal economist and historian, Ludwig von Mises, these contradictions and inconsistencies determined the bankruptcy of German social democracy.

With the fall of the imperial regime, businessmen, defying central planning, had resumed production for export in order to buy food and raw materials in neutral countries and in the Balkans. The businessmen succeeded in their efforts and claimed to have saved Germany from starvation and misery. Their contemporaries dismissed them as freeloaders, but they were glad to finally be able to acquire much-needed items. The unemployed found work again, and Germany began a return to normality. For their part, German workers of all kinds did not care much for socialization. They gave more importance to higher wages, unemployment benefits and reduced working hours. The workers' councils, viewed with suspicion by the institutions and union leaders, lost all their revolutionary substance and their political role by article 165 of the Constitution and the Factory Councils law of February 4, 1920.

The attempt at agrarian reform, timid and full of contradictions, did not imply a substantial change in the living conditions of farmers or in the property structure. According to 1922 estimates, barely 2% of landed property affected by the law had been redistributed, a situation that would not improve over the years.

Armed gangs and the army

The November revolution led to the emergence of the Freikorps (free companies) and the Wehrorganisationen (defense organizations), armed bands led by adventurers, a phenomenon that did not it had been seen in Germany since the Thirty Years' War. These free companies (such as Franz Seldte's Stahlhelm, Fritz Kloppe's Wehrwolf, and Ernst Röhm's Sturmabteilung) were made up of officers fired from the former Imperial Army, who were joined by demobilized soldiers and young cadets, none of whom wanted to return to their posts. civilian life. They offered their protection to landlords and peasants, and while they initially protected civilians from communist attacks and defended gains on the eastern front, soon the unwieldy gangs turned into violent looters and blackmailers. Given the impossibility of dissolving them, they ended up being integrated into the Reichswehr, which, apart from creating a conflict with the allies, was another of the ingredients of the failure of the Weimar Republic: the survival of a rapacious, conquering and anti-parliamentary army. The military institutions and the navy came to keep the imperial colors (black, red, white) instead of the republicans. Once the communist threat was eliminated, his collaboration with the republican authorities ended. The officers enjoyed incredible autonomy, maintaining their militaristic ideology, their monarchical affections and their aristocratic lifestyle. Facing the gallery, the army rejected any involvement with the armistice and the signing of the peace of Versailles. Nationalists and the military claimed that since 1914 they had managed to keep German territory inviolate, camp for four years in France and keep three-quarters of Belgium and a good chunk of France occupied on the day of the armistice. Although the army had lost both the battle and the war, neither the civilians nor the military had the feeling that they had been defeated, except in some conscious sectors of the rear or front. In this context, the legend of the stab in the back allowed them to maintain their mythical halo of invincibility and accuse the "traitorous civilians" of defeat. On November 11, the troops paraded through Berlin, and Ebert greeted these soldiers "returning undefeated from glorious combat", thus consecrating the myth on which nationalist and Hitlerite propaganda was to feed.

The Treaty of Versailles

Annexed by neighbouring countries Managed by the League of Nations Germany (1919-1935)

The Treaty of Versailles was a peace treaty at the end of World War I that officially ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Countries. It was signed on June 28, 1919 in the Hall of Mirrors of the Palace of Versailles, exactly five years after the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria, one of the events that triggered the start of the First Great War. Although the armistice was signed on November 11, 1918 to end the actual fighting, it took six months of negotiations at the Paris Peace Conference to conclude a peace treaty. The Treaty entered into force on January 10, 1920.

Of the many provisions of the treaty, one of the most important and controversial provisions required Germany and its allies to accept full responsibility for causing the war and, under the terms of Articles 231-248, must disarm, conduct important territorial concessions and pay multimillion-dollar compensation to the victorious states. The Treaty was undermined early by later events after 1922 and was widely violated in the 1930s with the rise of Nazism to power.

The years of crisis (1919-1923)

The first years of the Weimar Republic were years of political crisis, economic, financial, monetary crisis and loss of money, coup attempts and separatism, which would shake the young Republic until the end of 1923. Events happened at an insane rate and its complexity is often inexplicable. The new Republic suffered the hostility of the nationalist bourgeoisie, the Army and both extreme right and extreme left groups.

After the radicalization of the situation in Bavaria, in Berlin, in the spring of 1919, Gustav Noske tried to completely eliminate the communist opposition, which he considered the most serious danger. At the beginning of March, allying himself with the freikorps , he organized a new bloody repression against a strike. In the course of which the communist leader Leo Jogiches, successor to Liebknecht and Luxemburg, was assassinated (March 10), along with several hundred workers. A similar repression was organized in some other cities such as Magdeburg or Leipzig. According to Claude Klein, Elsewhere, such as Saxony, the situation was anarchic rather than revolutionary, sometimes even simply "far-left terrorism".

The right-wing reaction and the Kapp coup

Taking advantage of the counterrevolutionary wave, the reactionary right attacked the republican regime head-on and with increasingly accentuated violence; first through parliament, essentially from the DVNP of former imperial minister Karl Helfferich. In December 1919, Helfferich unleashed a campaign of unprecedented violence against Finance Minister Matthias Erzberger, questioning even his personal integrity and his political capacity. A trial for defamation took place, which lasted from January to March 1920, and excited public opinion. Erzberger was the victim of an assassination attempt by a young nationalist, but finally, on March 12, the trial was a complete success for Helfferich, as the court recognized the merits of the accusations. This victory of the nationalists against the republicans forced Erzberger to temporarily withdraw from political life.

The day after the judicial ruling, on March 13 at 6 in the morning, the Kapp coup began, which channeled the latent discontent in the Reichswehr throughout the year 1919. The Reichswehr was threatened by the reduction of troops established by the Treaty of Versailles, as well as by the demand for the extradition of certain war criminals and the threat of dissolution of the most openly anti-republican bodies, such as the two Erhardt brigades, stationed in Silesia, particularly agitated and ultranationalist, which in fact already wore the swastika as their emblem. General Walther von Lüttwitz and Wolfgang Kapp, a high-ranking Prussian official, tried to organize this discontent and impose a military dictatorship. The marine brigade entered Berlin, occupying the ministries and centers of power. Noske, knowing what was happening, requested the intervention of the Reichswehr, but Hans von Seeckt, one of his bosses, refused, claiming that "The Reichswehr does not shoot at the Reichswehr". Kapp was proclaimed chancellor, while the government fled, taking refuge in Dresden and then in Stuttgart. The population welcomed the ultranationalists with discontent, quickly organizing worker and popular resistance. The general strike broke out, and in a few hours Berlin was completely paralyzed. After four days, the victorious coup leaders gave up and went home, leaving everything a fraud. Not so in other German cities, where there were up to 300 deaths. In any case, it had been shown that the left had an effective weapon in the general strike, and Noske, the organizer of the counterrevolutionary repression, lost his position. But the failure of the Kapp coup in no way meant a victory for the republican regime. Quite the contrary, the attempt ended with a general amnesty, the promotion of Seeckt to the supreme command of the army and the refusal of a total restructuring of the Reichswehr, more than committed to the coup plotters. Various authors consider that the systematic indulgence with right-wing extremists, in the belief that they were the only ones capable of defeating Bolshevism, was one of the key elements in the failure of the Weimar Republic.

Worker uprisings and left-wing coup attempts

The regime of the Weimar Republic was also endangered by movements on the left. From 1919 to 1923, each year and in a permanent way, various labor movements developed. Sometimes they were just simple riots, and other times they were outright insurrections and attempted coups. Immediately after the Kapp coup there was a real putsch attempt in the Ruhr area, ruthlessly suppressed. Much was made of the 'Red Army', which occupied several cities in the Ruhr area. In Saxony and Thuringia, Max Holz, on many occasions disagreeing with the Communist Party itself, carried out military actions arming the workers (especially initially unemployed workers) attacking the army as a guerrilla on many occasions, the army reaching group more than 15,000 workers in a short time. The number continued to rise, but despite the successes of this workers' army, the insurrection did not successfully spread to the rest of Germany, which led to its dissolution and the withdrawal of the call for insurrection and the General Strike that the communists had been spreading and organizing for days. The repression was terrible, but Hölz managed to escape.

The year 1921 was marked by revolutionary attempts. A general strike was proclaimed, but it was a failure. In central Germany there was extensive fighting, especially in the Leuna factories in Mansfeld, in Saxony, where the fighting lasted several days. On March 31 it was all over, and a few months later Holz was arrested and sentenced. This meant the collapse of German communism. The German proletariat was not for the revolution, and the continued revolutionary attempts of the communists discredited them. This was exploited by the nationalists, and paved the way for Hitler's rise ten years later.

The 1920 elections

The Kapp coup turned against the Weimar coalition, which promptly called new elections. The National Assembly, which was still in session, was dissolved and the first Reichstag was elected on June 6, 1920. These elections were a major failure for the Weimar coalition: the Democrats lost 29 seats, the Social Democrats 51 and the Zentrum 6, while the Nationalists won 22 seats, the Populares 43, the Independent Socialists 59 and the Communists, who did not present candidates in 1919, won 4 seats. The SPD, condemned by all, was the one who lost the most. He left the government, and a new “bourgeois” coalition was formed under the leadership of Fehrenbach (ZP). With this crisis, the correlation of forces changed substantially, and Social Democracy remained in opposition, except for a brief period in coalition with the zentrum and the Democrats, under the chancellorship of Joseph Wirth. The anti-republican parties (DVP and DNVP) progressively became the axes of the ruling coalitions, supported by a public opinion hostile to the payment of reparations and the territorial losses dictated in the peace treaty.

With this victory, the right did not lay down its arms, quite the contrary. The years 1921 and 1922 were distinguished by numerous political attacks, destined to produce a climate of insecurity. Several terrorist organizations were created on the extreme right, the best known of which was the OC (Consul Organization). Karl Gareis, an independent socialist and member of the Landtag of Bavaria, was assassinated on June 9, 1921. On August 26 of the same year, Erzberger was assassinated; the following year, the Minister of Foreign Affairs Walther Rathenau, on June 24, 1922.

Hyperinflation

Since November 23, 1922, the government was headed by Wilhelm Cuno, of the DVP, former director of the Hamburg-Amerika shipping company, with the SPD again in opposition. The new government was faced with the problem of war reparations. When reparations were delayed, Raymond Poincaré's revanchist France had a pretext to militarily occupy the Ruhr in January 1923. Powerless and totally overwhelmed by events, the Cuno cabinet disappeared amid general indifference on 12 August. The new chancellor, Gustav Stresemann, formed a unity government (from the SPD to the popular ones), but by then Germany had already fallen into the abyss.

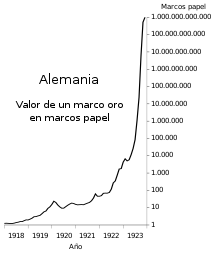

When World War I broke out on July 31, 1914, the Reichsbank suspended the convertibility of currency into gold, allowing them to start issuing large amounts of paper money. At the end of the war, its financing had cost the Reich 185,000 million marks, a cost that must have doubled if one takes into account that the mark was sold at the end of the war at half its previous value. Of this $185 billion, not even a fifth ($38 billion) came from taxes, while 50% ($97 billion) came from borrowing, and 27% ($50 billion) from short-term treasury bonds. term. In 1918 the Reichsbank recognized a floating debt of 49,000 million, and an accumulated one of 96,000, while the amount of money in circulation had increased from 2,900 to 18,600 million. The financing instruments to which the imperial regime had resorted had meant, therefore, a growth of 600% of the budget deficit and 500% of the monetary mass in circulation. In this sense, inflation was lower than expected, since the depreciation of the German currency with respect to the dollar between 1914 and 1919 was approximately half: from the relationship 1 dollar: 4.2 marks, it went to 1 dollar: 8.9 marks in January 1919. Prices only had risen 140% by December 18, a similar situation to the English one.

With regard to war reparations, after several preliminary meetings in 1920, the Paris Conference of 1921 had set them at 269,000 million gold marks, to be paid in 32 annual installments, a figure that was reduced to 132 000 at the London Conference. Regardless of the clumsy method used to fix them, these sums were small in comparison with the effort that the future Nazi Germany endured to rearm itself militarily. Reparations came to represent not much more than 1 or 2% of GDP, and around a third of the deficit; they amounted to a total of 8 billion marks per year, that is, less than a quarter of German war expenditures each year of the First World War. These repairs were paid for with money borrowed from the Allies themselves, which the Germans never returned. Between September 1924 and July 1931 Germany paid, under the Dawes and Young plans, 10,821 million marks in reparations. He did not pay anything else. On the contrary, its public and private external debt imported approximately 20.5 billion marks in the same period, to which can be added some 5 billion marks of foreign investment in Germany; in the same period Germany invested about 10 billion marks abroad.

To cope with the increase in public spending caused by its social policy without raising taxes, the German government began to print more and more paper money, clinging to the mistake that the devaluation of the currency was due, not to the monetary and credit expansion, but to the unfavorable balance of payments. Until January 1922, the German currency was devalued to 36.7 marks per dollar, at which time inflation took on abnormal proportions. At the beginning of 1922 prices increased by approximately 70%, which had caused an increase in wages (only 60%). In December 1922 the dollar already reached the average of 7592 marks and after the occupation of the Ruhr in January 1923, its fall was endless. By then most people had lost all their savings, and taxpayers realized that simply by delaying their taxes, the depreciation of the mark would wipe them out. The Treasury collapsed, and the government, with less and less income, financed itself by printing even more banknotes. The dollar went from 17,972 marks to 350,000 in July, 1 million at the beginning of August, 4 million in the middle of the month, and 160 million at the end of September. The collapse of the mark was so absolute that it ceased to function as an exchange value, with the consequent collapse of the German economy. By October 1923, 1% of government revenue came from the usual channels, and 99% from the issuance of new currency. Around November 15, the unimaginable amount of 4.2 trillion marks was paid for a single dollar. It was at that time that Hjalmar Schacht put into effect the Rentenmark, a currency for internal use backed by the economic wealth of the country. Some time later the new Reichsmark was created, which replaced the old coins from October 11, 1924. The old notes were put out of circulation on June 5, 1925.

Although the “Rentenmark miracle” solved the problem of hyperinflation and stabilized the economy, its devastating consequences remained the same. Social differences were greatly accentuated, and, as usual, the richest not only were not affected by hyperinflation, but also benefited. Large companies were thus able to get rid of their debts, reduced to zero, very quickly. Some big industrialists, thanks to this, were able to multiply their fortune tenfold: the typical example is Hugo Stinnes, the so-called "new Kaiser", who created a huge industrial trust by acquiring ruined companies at low prices, thanks to loans that he repaid at the end with worthless marks. Economic power emerged stronger from inflation, which is the fundamental difference between the 1923 crisis and the one that brought Hitler to power in the early 1930s.

The middle class, especially the rentiers, were ruined long before inflation reached delirious proportions. Savers lost all their money, while the people who spent their money buying real estate and tangible goods, the people who got the most in debt, had gotten rich. For the average German it was the world turned upside down: people who followed the rules found themselves cheated and betrayed, while those who broke them got rich. In addition, coupled with the absolute loss of the mark's value, came a skyrocketing price hike. The hyperinflation of 1923 ended the prewar German society. The reduction of public spending and social benefits to balance people who arrived at the moment when they were most needed, after a large part of the population had gone bankrupt. Depressed and disillusioned with republicanism, its political class and mercantilist poverty, the people began to give credit to the new alternatives, such as Nazism.

Faced with misery, hunger and lack of health care, leisure became a means of escape for the masses, which created a powerful leisure industry (Unterhaltungsindustrie) around the press, radio and, above all, the cinema, in a true wave of Americanization and social escapism. It was a time of splendor for theatres, nightclubs and cabarets, a time of exceptional intellectual and artistic wealth, with the rise of the avant-garde, represented by Otto Dix and Bertolt Brecht.

The Stresemann Era (1923-1929)

At the end of 1923, inflation ended with the creation of the new framework. Until 1926 a difficult transition period followed. The immediate effect of stabilization was the end of the unlimited demand for goods of the inflation period. Economic activity immediately declined significantly and unemployment increased, affecting more than a quarter of the workers at the end of 1923. However, once the Dawes plan came into effect in mid-1924, international confidence in the mark and international loans began to flow into Germany, attracted by high interest rates. With the end of the protection against foreign competition that inflation brought with it and with the new course of foreign exchange, German industry had to face two problems. One was to shift the balance of industrial production to meet the postwar pattern of domestic and world demand, a problem less acute in Germany than in England, but important in industries such as shipyards and coal. The other was the result of the nature of some inflation period investments, many of which proved uneconomic under normal competitive conditions. Hence the late 1920s was a period of "rationalization," with high unemployment peaking in 1926. Industrial production, however, increased after 1926., in 1927 it exceeded the prewar level and continued to rise until early 1929. Workers' profits increased by about a third between 1925 and 1929.

The Rise of National Socialism (1930-1932)

The Great Depression (1929-1931)

On October 3, 1929, Gustav Stresemann died, after having worked for six years to help Germany partially recover its position in Europe.

His political triumphs were overshadowed, however, because three weeks after his death, the Great Depression struck, loans from the United States stopped coming, and the German middle class suffered again. Millions of people were made unemployed, thousands of small businesses closed, and production fell by half in three years. This was the desperate situation that the National Socialist Party took advantage of to recover the position that it was slowly losing.

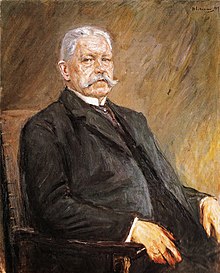

In March 1930, the coalition that maintained the government of Social Democratic Chancellor Hermann Müller collapsed, and he had to resign. The Catholic centrist Heinrich Brüning succeeded him. Brüning had been named chancellor by President Paul von Hindenburg, thanks to a recommendation from General Kurt von Schleicher, who would later also participate in his fall.

Unable to win Reichstag support for the approval of a financial program, Brüning turned to Hindenburg, who responded by using his constitutional powers to pass the law by presidential decree, bypassing the Reichstag. Parliament immediately demanded that the president withdraw his decree, but at Brüning's request, Hindenburg dissolved it in July 1930. New elections were scheduled for September 14, and the Nazis exploited popular discontent in the election campaign.

The 1930 federal elections catapulted the Nazi Party from being the ninth party in the Reichstag to becoming the second, surpassing even Hitler's expectations. In the last federal election, the Nazis had won some 810,000 votes, which equaled 12 seats, but on September 14 they secured 107 seats by garnering 6,409,600 votes. The communists also gained voters, and the moderate parties were weakened by being abandoned by the middle class.

After these elections, the Nazi Party found industrialists who financed them more easily, among whom was Fritz Thyssen. Some corporations also supported them, among them the Allianz insurance company, and the Deutsche Bank and Dresdner banks Bank. On the other hand, the elections ended Brüning's hope of ruling through parliamentary democracy, and he became more dependent on Hindenburg, as he could not obtain an absolute majority in the Reichstag to pass his laws.

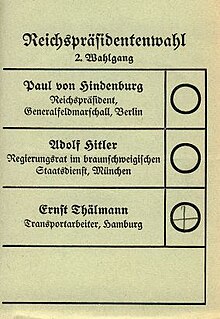

Presidential elections (1931-1932)

1931 was another bad year for the unstable republic, with the number of unemployed topping five million. In May, Credit-Anstalt, the main Austrian bank, declared bankruptcy, and two months later Danat-Bank, one of the main German banks, was intervened by the government. However, 1931 brought an additional problem whose effective solution was essential to prolong the life of the Weimar Republic. Hindenburg's presidential term ended in the spring of 1932, and although Hitler did not have the majority support of the people, his opponents were so divided that a victory for the Nazi leader seemed imminent. Brüning drew up an ambitious plan whose objective was to ensure his government and neutralize the Nazi threat to end the Republic. With the support of two thirds of the legislative chambers, the Reichstag and the Reichsrat, the chancellor would suspend the presidential elections, in this way, Hindenburg's term would be postponed until his death, which would occur soon since the president had over 84 years.

However, when this finally happened, Brüning would again face the threat of Hitler running for the presidency, so he quickly devised another solution: he would propose to Parliament to transform the Republic into a constitutional monarchy, with Hindenburg to be regent until his death. death, then one of Crown Prince William's sons would assume the throne. Meanwhile, Brüning would negotiate the cessation of indemnity payments with the Allies, and would demand that they disarm at the level of Germany, as they had promised in the Treaty of Versailles. If the Allies refused, Germany would initiate its own rearmament. With this plan, the chancellor intended to make the Republic popular, and neutralize Hitler's aspirations to come to power.

The first to oppose Brüning's plan was Hindenburg. The president rejected any other Hohenzollern, except William II, taking the throne, and also resented that the new monarch would reign with the limitations of a constitutional monarchy. To make matters worse, Hindenburg told Brüning that he would not seek re-election, so the threat of Hitler acceding to the presidency became more and more latent. The second obstacle was the Nazis and the nationalists, the latter led by Alfred Hugenberg, whose seats in Parliament were necessary for the postponement of the elections to be approved. elections. In the first days of January 1932, Hitler and Hugenberg had separate meetings with Brüning. Hugenberg flatly rejected the proposal, but Hitler wrote a direct letter to Hindenburg, where he conditioned the chancellor's resignation for him to agree, but Hindenburg did not give in to the blackmail of the "bohemian corporal", as Hitler called his friends. backs.

Punched, Brüning had to convince Hindenburg to run. Finally, the old Marshal agreed, but he resented the chancellor, since he not only blamed him for having badly negotiated with Hitler, but also that in these elections Hindenburg would no longer have the support of the nationalists, his natural allies, but would instead have He had to be supported by the Social Democrats, with whom he had never sympathized. become unproductive, but instead generated debts to the state (see Osthilfe). In addition, Brüning also lost the support of Schleicher, who began planning his downfall after the upcoming presidential election, as the chancellor's support was necessary to secure re-election. of the current president.

In these new elections, Brüning threw himself headlong into seeking the re-election of Hindenburg, who was too old to run an electoral campaign. Hitler also launched his candidacy after hesitating for weeks, and only days after he had obtained German citizenship. Hitler had the political support of his party alone, and funding from Thyssen, among other industrialists. Hindenburg was supported by the Social Democrats and some important magnates, including Carl Friedrich von Siemens (Siemens AG), Carl Bosch (IG Farben) and Carl Duisberg. Junkers, nationalists and royalists supported Theodor Duesterberg, leader of the Stahlhelm. The communists re-launched their president Ernst Thälmann.

On March 13, the presidential election was held, and although Hindenburg obtained almost 20 percentage points of difference with his main opponent, Hitler, he lacked 0.4% to obtain the absolute majority necessary to access the presidency. On April 10, the second round was held, and this time Hindenburg managed to obtain more than 50% of the votes, although Hitler obtained 37% of the votes. In this second round, Duesterberg withdrew, but the conservative sectors did not support Hindenburg, but Hitler.

Despite the fact that the Nazis had obtained five million more votes than in the 1930 elections, Brüning considered that this was the necessary moment to order the abolition of the Sturmabteilung (SA), led by by the Nazi Ernst Röhm, heeding the requests of the Prussian and Bavarian police, who claimed that Röhm was planning a coup. Hindenburg, advised by his chancellor, signed the decree ordering the dissolution of the SA on April 13, but this never took place due to Schleicher's intervention. General Schleicher had been meeting with Röhm, who had convinced him to attempt to transfer command of the SA to the state. Schleicher presented this idea to his former tutor, General Wilhelm Groener, Minister of Defense and Brüning's ally, but the latter was vehemently opposed, so Schleicher decided to get rid of both Brüning and from Groener.

Fall of Brüning (1932)

On April 24, the Nazis won a clear majority in the Prussian regional Diet elections, and Brüning lost the parliamentary support of this important state. Four days later, Schleicher met with Hitler, and Hitler agreed to support a new government on the condition that the abolition of the SA be lifted and Brüning fall. Schleicher had already gone ahead and pointed out his friend, General Kurt von Hammerstein-Equord, Reichswehr (Army) Chief of Staff, that this order against the SA was not supported by the Army. With the support of Schleicher, the presidential secretary, Otto Meissner, and the president's son, Oskar They also approached the Nazi leader, who assured them that in order to revive parliamentary democracy, they must pressure Hindenburg to dissolve the Reichstag once Brüning left the Chancellery.

To get rid of Groener, Schleicher told Hindenburg that the Defense Minister had had a son five months after they were married. He then led him to believe that the Iron Front (ex-Reichsbanner), a Social Democratic militia, was he was preparing to start a civil war. After being humiliated in the Reichstag by Göring and Goebbels, Groener faced attack from his "adopted son", Schleicher, who told him that the Army was asking for his resignation. On May 12, after Hindenburg had turned his back on him, Groener resigned.

Chancellor Brüning understood that he would be the next to fall, but he traveled to Geneva to meet with French Prime Minister André Tardieu to finally negotiate the payment of war reparations. This potential political victory for the Chancellor was destroyed by Schleicher, who told the French that Brüning would soon be replaced, and that negotiating with him was futile. As a consequence, Tardieu canceled the meeting at the last moment, citing illness. Defeated, Brüning returned to Berlin, where he was recalled by Hindenburg on May 29. Hindenburg had already been convinced by Meissner that there was a way to return to parliamentary democracy, and the elderly president had already decided to have Brüning resign. He told him that he had heard that the chancellor had ministers with Bolshevik plans, and that he no longer He would pass his laws. Since Brüning did not have a majority in the Reichstag, nor did he have the support of the president, it was impossible for him to exercise his functions, so he resigned the next day.

Papen's government and federal elections (1932)

The new chancellor, Franz von Papen, was a Catholic centrist from the same party as Brüning, and like Brüning, came to power through Schleicher's influence over Hindenburg. With this appointment, Schleicher thought Papen would he would get the centrists to support the new government, and since the Nazis had already promised to support him, he would get a parliamentary majority to govern. But Hitler did not want his revolutionary movement to be linked to the Papen government, and when centrist leaders told the new chancellor that the Nazis should be exposed for passing unpopular laws, he refused. to do it.

As a consequence, Papen was abandoned by his own party, and was left without candidates to form his cabinet. Hindenburg had to quickly form a cabinet for his chancellor, made up mainly of nobles, for which it was derisively called the cabinet of barons. On June 3, the Prussian Diet voted on a motion of no confidence against the democratic government of Otto Braun. This motion, initiated by the communists, only served to make the Nazis in Prussia more powerful, and parliamentary democracy suffered the final blow.

According to the agreement, Papen dissolved the Reichstag and called new federal elections for July. Schleicher, now Minister of Defense, then worked with Hindenburg to annul the dissolution order against the SA, which was carried out on the 15th. of June. Street clashes between the Nazi and communist militias then began, and dozens died in them. In the State of Prussia, the fighting was more intense, and after Schleicher presented evidence about an alleged alliance between the Prussian regional government and the communists, Papen invented the position of Reichskommissar, replacing Otto Braun as ruler of Prussia.

This episode, known as the Prussian coup, was not resisted by the Social Democrats, Braun even went on vacation at this time, only the communists proposed a general strike, but the population did not respond. Some historians consider this coup Papen did indeed mark the end of the Weimar Republic, even though the Nazis did not come to power for eight months.

Germany's July 1932 federal elections were held on July 31, and although the Nazi Party became the most popular party, winning 230 seats, only 38% of the electorate supported it. In any case, on August 5, Hitler met with Schleicher and sued him for the Chancellery. Hitler left the meeting convinced that Schleicher had agreed, but on August 12, the latter refused to give him the government without reaching a parliamentary majority. To achieve this, Hitler would have to form a coalition with the center, but this would limit his actions., and refused. The next day, Hitler had another meeting with Schleicher, this time in the presence of Chancellor Papen, without obtaining the desired results. He was later summoned by Hindenburg, who coldly reproached him for not having kept his word to support Papen.

Unable to seize power, the Nazi Party began to face severe funding shortages, and some of its leaders, notably Gregor Strasser, began to doubt Hitler's leadership. Strasser began talks with the centrists, with Hitler's approval, and managed to get them to appoint the president of the Reichstag. In this way, Hermann Göring, until now a little-known figure, led Parliament. Göring and Hitler attempted to form a coalition government with the centrists, but the centrists would not compromise, and Hitler's wish to achieve the chancellorship constitutionally was not fulfilled again.

This rapprochement between the Center and the Nazis was not lost on Papen, who obtained a letter of dissolution of the Reichstag from President Hindenburg, with the aim of dissolving it before a coalition opposed to him could be formed. On September 12, Papen attended the Reichstag, and after receiving a vote of no confidence from the parliamentarians, he dissolved Parliament and called new federal elections for November 6. Papen believed that by then, his economic measures would have brought economic stability to the nation again.These new elections increased the mistrust of Strasser, who now had the support of Wilhelm Frick, and he predicted that the Nazi Party would lose votes.

Federal elections in November proved Strasser right, as the Nazis lost more than two million votes, and National Socialist parliamentarians fell from 230 to 197. Now, Strasser dared to publicly demand Hitler to decline his aspirations to the Chancellorship, and to be content with having part of the power. Papen also pressured Hitler, writing him a letter and inviting him to negotiate, but Hitler made so many demands that Papen decided to abandon the idea of reaching an agreement with him. Rejected by the communists, the Nazis, the social democrats and the centrists, the chancellor had only the support of the nationalists, who held only 50 seats in the Reichstag. As Papen was unable to obtain a parliamentary majority, Schleicher asked for his resignation, which became effective on November 17. Hindenburg immediately called the leader of the most popular party in Germany, Adolf Hitler.

On November 19, Hitler met Hindenburg again and sued the Chancellorship. The president would offer him the chancellorship only if he managed to win a majority in the Reichstag, otherwise he would prefer Papen to continue to rule Negotiations dragged on for a week, to no avail. Meanwhile, Schleicher met with Strasser, who suggested that the Nazis might join a government of his, rather than Papen's. On December 1, Hindenburg called Papen and Schleicher, but at the same time, in Weimar, Strasser and Frick tried to convince Hitler to support a Schleicher government, while Goebbels and Göring opposed them.

Papen was convinced that Hindenburg would rename him Chancellor, and he proposed amendments to the constitution during his new government. Schleicher, who had been disenchanted with Papen for several weeks, opposed these changes, assuring Hindenburg that he would get Strasser to split the Nazi Party, and with the help of the Social Democrats, achieve a parliamentary majority to govern without recourse to the president. Hindenburg was initially hesitant, and asked Papen to form a new government, but the next day Schleicher turned half the cabinet against Papen and after leading the president to believe that civil war was inevitable, Hindenburg agreed to change. to Papen. However, Hindenburg still had confidence in Papen, and this bond was enough for the outgoing chancellor to return the favor to his treacherous defense minister within weeks. Furthermore, Hitler's response came too late for Schleicher, the Nazis would not support his government and recommended that he not accept the Chancellorship.

Schleicher government and Papen-Hitler coalition (1932-1933)

On December 3, Chancellor Schleicher met Strasser in secret, offering him the Vice-Chancellorship. In the Thuringian regional elections held on that day, the Nazis lost 40% of the vote, and Strasser he became convinced that if Hitler did not abandon his "all or nothing" policy, the Nazi Party was doomed. On December 5, at the Hotel Kaiserhof, Strasser tried to convince Hitler to support Schleicher, to no avail. Two days later, Hitler had another meeting with Strasser on the same subject, but this time Strasser retired to his room at the Excelsior Hotel in great irritation. After resigning his post in a violent letter, Strasser sent his version of the story to the newspapers, threatening to split the party in two, just as Schleicher had wished. Hitler was furious, telling Goebbels that if the party was divided, he would commit suicide. Frick tried to reconcile him with Strasser, but the latter was already on his way to Munich, planning later to travel to Italy, where he believed that Hitler would beg him to return. Hitler managed to put an end to Strasser's threat. Strasser's friendly leaders were dismissed, and the remainder were summoned to Berlin where they were forced to sign a declaration of allegiance to Hitler. In addition, Hitler, Goebbels and Robert Ley began tours of Germany, where they met with local leaders and tried to convince them that the seizure of power was near.

For his part, Papen had been working on the downfall of Schleicher and on January 4, 1933, met with Hitler secretly, though the chancellor found out anyway. Papen proposed a government where Hitler would be chancellor, but the ministers would be his. After the war, Papen denied having offered the Chancellorship to Hitler at this meeting, but although this version is not the most widely accepted, other historians claim that Papen could not make this offer. At this meeting it was also possible to end the economic problems of the Nazi Party, thanks to the intervention of industrialists willing to finance the Nazi Party. In addition to financial aid, Papen inadvertently gave another weapon to Hitler: he informed him that Schleicher had obtained the Chancellorship because he had secured that he could obtain a majority in the Reichstag, and that Hindenburg was not going to offer him an order to dissolve Parliament. Thus, if the Nazis and the Communists joined n the Reichstag, they could end the Schleicher government whenever they wanted.

By mid-January, Schleicher's plan to destroy the Nazi Party through Strasser had failed. The latter, back in Germany, requested a conciliatory meeting with Hitler, but was rejected. On the other hand, Schleicher tried to place Alfred Hugenberg in his cabinet, to bring the nationalists closer together, but he had to give up in the face of Social Democratic resistance. The parliamentary majority escaped from Schleicher, and his position vis-à-vis the president, his main pillar, weakened.

Hindenburg's son Oskar and presidential secretary Meissner also participated in the downfall of the last chancellor of the Weimar Republic. On January 22, Oskar and Meissner secretly met with Hitler and Papen at the home of a friend of the latter, Joachim von Ribbentrop. Details of the meeting have not been released, but on the way out, Oskar told Meissner that the Nazis must seize power.

On January 23, Schleicher appeared before Hindenburg and declared that he had not been able to achieve a parliamentary majority. Papen was present and insisted that he would round up the Nazis if he ruled with them.On January 28, Schleicher appeared before Hindenburg and resigned. The decision to appoint a new chancellor rested once more with the president, and Papen was the choice he liked best. But Schleicher had already led him to believe that a new Papen government would not be recognized by the Reichswehr, so Hindenburg tasked Papen with forming a new government with Hitler as chancellor.

On January 30, 1933, Hitler was appointed chancellor of Germany, with a cabinet where the Nazis were a minority. Papen thought in this way to control Hitler, but very soon he would be surpassed.

The End of the Republic (1933)

Although since 1930 the chancellor of Germany had ruled without the approval of Parliament, ending parliamentary democracy, the German Parliament continued to exist as a fundamental pillar of the Republic. However, in March 1933, a few weeks after coming to power, Chancellor Hitler managed to obtain all the powers of Parliament, which since then became a sounding board for the Executive, devoid of will of its own.

Last election campaign

Although Hitler had been appointed chancellor, his position was far from secure. Not having a parliamentary majority, he needed the support of President Hindenburg to approve all his decrees and laws. This meant that he had to count on conservative and nationalist elements in his "revolutionary" cabinet, to please Marshal Hindenburg and his right-hand man, Papen. Indeed, in this eleven-member cabinet, only three were Nazis, the rest were allies of Papen or Hugenberg. To further complicate their precarious political situation, elements of the Army and conservative sectors looked askance at the National Socialist movement, specifically at the leftist[citation needed] elements grouped around Ernst Röhm, leader of the violent brownshirts. Finally, regional governments were still a major force, and Bavaria was becoming a zone of Social Democratic resistance, as its government was suspicious of the Nazis.

However, Hitler decided to take over Parliament first; if he did not achieve a parliamentary majority quickly, the elderly president could withdraw his confidence, leaving him unable to govern. At his first cabinet meeting, held on the day he took office, this problem was discussed. The National Socialists and Hugenberg's Nationalists only had 247 seats in Parliament, 46 seats short of the majority needed to govern. Although they could try to attract the centrists of Kaas, with whom they would have a majority to govern; Hitler would be unable to carry out the profound reforms necessary to carry out his National Socialist revolution, since he would need the support of two thirds of Parliament, some 389 seats. Since the non-Nazi elements in Hitler's cabinet were not interested in achieving such a majority, Hitler took it upon himself to sabotage the negotiations with the centrist leader, Monsignor Ludwig Kaas, and led his cabinet to believe that no agreement was possible. with the Center. Hitler then asked Hindenburg to hold new federal elections. To calm Papen and Hugenberg down, Hitler assured them that regardless of the outcome of this election, his men in the cabinet would not be ousted.

New elections were set for March 5. The National Socialist Joseph Goebbels was optimistic about them, writing in his diary:

Now it will be easy to carry the campaign, because we can use all the resources of the state.Joseph Goebbels

As if that weren't enough, a meeting of leading businessmen was organized at Hermann Göring's presidential palace on February 20, attended by Hitler and Hjalmar Schacht. Among the new businessmen sympathetic to Nazism, Gustav Krupp stood out, who until a month ago had been an opponent of Hitler. After Hitler promised to end Marxism and rearm the Army, Göring promised that these would be the last elections for the next ten years or even for the next hundred years.

However, in a society as politically divided as Germany's in 1933, a powerful electoral campaign was not enough to achieve the majority desired by Hitler. Thanks to Goebbels' diaries it is known that the Nazis were expecting a communist insurrection in the first days of their government, which they would use as a justification to violently suppress this movement. To catalyze this uprising, the Nazis began to persecute the communists and the social democrats. The demonstrations of these parties were prohibited, and their press was continuously suspended. The "brownshirts" They were in charge of harassing these groups, which soon spread to the centrists. In total, 51 opponents of the National Socialists died in the election campaign, although, on the other hand, the Nazis recorded 18 fatalities in their ranks. Using his position as Prussia's Minister of the Interior, Göring created a parallel police force of 50 000 men, made up exclusively of members of the 'brownshirts', the SS and the 'Stahlhelm', all of these nationalist paramilitary organizations. In addition, he threatened police officers who refused to use their weapons against the opposition concentrations.

However, despite all these provocations, the coup attempt by the dissidence did not take place. However, the opposition remained as divided as before. On February 23, the Social Democrats asked the communists if they could unite before the disaster was complete. Ernst Torgler, the leader of the communist group in the Reichstag, responded that it was first necessary for the Nazis to seize all power, so that then the "revolution of the proletariat" could occur, which he estimated would occur "four weeks" impatient, the Nazis then decided to fabricate evidence that an opposition conspiracy was being mounted against them. On February 24, Göring's parallel police raided the headquarters of the Communist Party of Germany, which had been abandoned when Hitler rose to power. This did not stop Göring from announcing that he had uncovered documents proving that a conspiracy against the government was afoot. This announcement was met with skepticism by the German public, including among conservative pro-government sectors.

The destruction of the Reichstag

On the night of February 27, 1933, the Reichstag building caught fire. Several high-ranking government officials rushed to the scene, Göring being one of the first to arrive. Immediately, he began to accuse the communists of being behind this act.The capture near the building of Marinus van der Lubbe, a Dutch communist who days before had threatened to set the fire, seemed to confirm Göring's accusations. He claimed to have evidence implicating the communists, which was never presented, and further proclaimed:

Every communist officer must be executed where he appears.Hermann Göring

Although not all the details are known about how the fire originated, there are many testimonies obtained after the war that point to Göring as responsible. According to Rudolf Diels, head of the Gestapo, Göring had ordered him, before the fire, to prepare a list of people who should be arrested once it occurred. Although van der Lubbe's trial determined that he had not had enough elements to start a fire so quickly and in such dispersed points, this did not prevent him from being found guilty and beheaded. In addition, Torgler and three other prominent Bulgarian communists were either arrested or turned themselves in to authorities after Göring publicly accused them of being involved in the fire. Although these four were found not guilty, this sentence came too late to positively influence the communists in the federal elections.

The day after the fire, Hitler petitioned President Hindenburg for the approval of a decree known as the Reichstag Fire Decree. With this legal weapon, the German chancellor could abolish freedom of the press, the right to free expression, the right to privacy of communications, and respect for private property. In addition, the central government could usurp functions of the regional governments if it deemed it necessary. Predictably, the Communists and Social Democrats found that under this decree it was impossible for them to finish the electoral campaign. On the same day, the Prussian government declared having found documents proving that the communists planned to carry out a civil insurrection after the fire. The publication of the "conspiracy" It was promised, but it never came to pass. Under all these outrages, former Chancellor Brüning called on President Hindenburg to intercede, but to no avail.

Thanks to the Reichstag fire decree, the Nazis were also able to confront the Bavarian regional government, which they accused of being separatist. There was some truth to these accusations, as Bavarian leaders were toying with the idea of making Prince Rupert of Bavaria the regional Head of State. On March 9, the SA began a march through Bavaria, raising the Nazi flag. in public buildings. That same night, the Nazis usurped regional power, sometimes using brute force against the ousted ministers. Prince Rupert, who had just been appointed regent, fled that night to Greece. On March 12, Hitler made a speech in Munich, pleased to have finally controlled one of the most autonomous states; Hindenburg approved of the chancellor's actions of him.

On March 5, the federal elections of 1933 were held. Despite the enormous electoral advantage of the Nazi Party, the Nazi leader failed to obtain the majority necessary to govern, and had to resort to his nationalist allies to achieve it. On the other hand, his centrist and social democratic opponents even won votes or suffered small losses; only the communists were heavily punished by losing a million votes. With these results, the two-thirds needed to amend the constitution continued to elude the Nazis.