War and peace

War and Peace (Russian: Война и мир, Voiná i mir), also known as War and Peace, is a novel by Russian writer Leo Tolstoy (1828-1910), who began writing in a time of convalescence after breaking his arm when falling from a horse in a hunting party in 1864. It was first published as magazine fascicles (1865-1869). War and Peace is considered the author's masterpiece along with his later work, Anna Karénina (1873-1877).

It is considered one of Tolstoy's finest literary achievements and remains an internationally lauded classic of world literature.

Publication of War and Peace began in the Russky Westnik (The Russian Messenger), in the January 1865 issue. The first two parts of the novel were published in said magazine over the course of two years and shortly thereafter they appeared separately edited under the title Year 1805. By the end of 1869 the entire work was printed.

It is unknown why Tolstoy changed the name to War and Peace. It is possible that he borrowed the title from Pierre-Joseph Proudhon's 1861 work: La Guerre et la Paix (War and peace in French). The title may also be another reference to Titus, described as a master of "war and peace" in Suetonius's Lives of the Twelve Caesars at 119. The complete novel was then called Voyná i mir (Война и мир according to the new spelling).[citation required]

The 1865 manuscript was republished and annotated in Russia in 1893 and has since been translated into English, German, French, Spanish, Italian, Dutch, Swedish, Finnish, Albanian, Korean, and Czech.

Tolstoy helped introduce a new kind of consciousness into the novel. His narrative structure stands out not only for God's point of view on and within events, but also for the way he quickly and fluently portrays the point of view of an individual character. His use of visual detail is often comparable to that of film, employing literary techniques that resemble panning, long shots, and close-ups. These devices, although not exclusive to Tolstoy, are part of the new style of novel that emerged in the mid-XIX century and the that Tolstoy proved to be a master.

It is one of the masterpieces of Russian literature and without a doubt of universal literature. In it, Tolstoy wanted to narrate the vicissitudes of numerous characters of all types and conditions throughout some fifty years of Russian history, from the Napoleonic wars to beyond the middle of the century XIX.

Some of the critics affirm that the original meaning of the title would be War and the world. In fact, the words "peace" and "world" are homophones in Russian and, moreover, since the Russian spelling reform of 1918, they are spelled the same (see fr:Orthographe russe avant 1918#Règles orthographiques). Before this reform, their spellings were different: міръ 'world', миръ 'peace'. This last figure in the original title of the novel: «Война и миръ».

Tolstoy himself translated the title into French as La Guerre et la Paix. He belatedly came up with this definitive title, inspired by the work of the French anarchist theorist Pierre Joseph Proudhon ( La Guerre et la Paix , 1861), whom he met in Brussels in 1861 and towards whom he felt a deep respect.

Realism

It is set sixty years before Tolstoy's time, but Tolstoy had talked to people who lived through the Napoleonic invasion of Russia in 1812. He had read all the standard Russian and French histories available about the Napoleonic Wars and had read letters, diaries, autobiographies and biographies of Napoleon and other protagonists of the time. In War and Peace about 160 real people are named or referred to.

He worked from primary source materials (interviews and other documents), as well as from history books, philosophy texts, and other historical novels. Tolstoy also used much of his own experience in the Crimean War to contribute vivid details and first-hand accounts of the structure of the Imperial Russian Army.

In War and Peace, Tolstoy criticizes standard history, especially military history. At the beginning of the third volume of the novel he explains his own opinion of how history should be written. His goal was to blur the line between fiction and history, to get closer to the truth, as he states in Volume II. [citation needed ]

Language

Although the book is written primarily in Russian, significant parts of the dialogue are in French. It has been suggested that the use of French is a deliberate literary device, to represent artifice, while Russian emerges as a language of sincerity, honesty, and seriousness. However, it could also simply represent another element of the realistic style in which the book is written, since French was the common language of the Russian aristocracy, and in general of the aristocracies of continental Europe, at that time. In fact, the Russian nobility often only knew enough Russian to order their servants around; Tolstoy illustrates this by showing that Julie Karaguina, a character in the novel, is so unfamiliar with the native language of her country that she has to take Russian classes.

The use of French decreases as the book progresses. It is suggested that this is to show that Russia is freeing itself from foreign cultural domination, and to show that a once friendly nation has become an enemy. Towards the middle of the book, various members of the Russian aristocracy are eager to find Russian tutors for themselves.

Plot

The plot is primarily set during the Napoleonic invasion of Russia following the intertwining history of four families:

- The Bezújov family (esentially Pierre)

- The Bolkonsky family (old Prince Nikolái Andréievich, Prince Andréi [or Andrew, depending on the translation] and Princess Mary)

- The Rostov family (Count Iliá Andréievich, Natasha and Nikolái)

- The Kuraguin family (Elena and Anatol).

Alongside the fictional characters, traditionally considered to be the true props of the plot, there are numerous historical figures, less defined and perhaps less "human": the Emperor Napoleon I, the Russian Emperor Alexander I and General Kutuzov.

In this novel there are three central characters, including: Prince Andrei Bolkonsky, intelligent and erudite if disgruntled; Count Pierre Bezukhov, who is the heir to a vast fortune and who carries the problems of being an important person in Russian society as well as a friend of Prince Andrei; and Countess Natasha Rostova, a beautiful and friendly young woman, from a family with many debts.

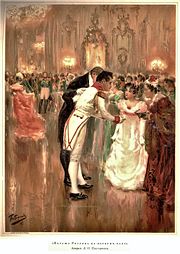

There are several parts to War and Peace, including: introducing the reader to the main characters; the Russian army in Europe (and the battle of Austerlitz); peace; the Russian War of 1812 and the defeat of the French armies after the occupation of Moscow; and the post-Napoleonic peace. He also describes the balls and meetings that took place in the homes of Russian aristocratic families in which the topic of conversation was the war and the Napoleonic invasion. The way in which Russian families were linked through marriage commitments and the importance that these had for society are also reported.

Tolstoy also writes extensively about his own views on history, war, philosophy, and religion.

Plot Summary

War and Peace has a wide cast of characters, most of whom are introduced in the first book. Some are actual historical figures, such as Emperors Napoleon and Alexander I. The scope of the novel is very broad, although it focuses on the lives of five Russian aristocratic families. The plot and the interaction of the characters take place around 1812, in the context of the Napoleonic Wars, during the Napoleonic invasion of Russia by French troops.

First volume

The novel begins in July 1805 in St. Petersburg, at an evening hosted by Anna (Annette) Pávlovna Scherer, a lady-in-waiting and confidant of the Queen Mother Maria Fyodorovna. Some of the main characters and aristocratic families of the novel are introduced upon entering the Anna Pavlovna drawing room. Pierre (Pyotr Kirilovich) Bezukhov is the illegitimate son of a wealthy count, Kiril Bezukhov, an older man whose days are ending. Pierre is about to get involved in a fight for his inheritance; Educated abroad at his father's expense after his mother's death, he is essentially good-natured, but socially awkward, and due in part to his overtly benevolent nature, he has a hard time fitting into Petersburg society.. It is known during the evening that Pierre is Count Kiril Bezukhov's favorite of all the illegitimate children.

Also attending the evening is a friend of Pierre's, the clever and sarcastic Prince Andrei Nikolaevich Bolkonsky, married to Liza Bolkonskaya (née Lise Meinen). He finds life in St. Petersburg society unctuous and disappointing when he finds out after getting married that his wife is empty and shallow: he makes the decision to be Prince Mikhail Kutuzov's aide-de-camp in the upcoming war against Napoleon.

The plot then moves to Moscow, the old city that had been the capital of Russia, contrasting its more provincial customs with those of high society in Saint Petersburg. The Rostov family is then introduced. Count Ilyá Andreivich Rostov has four teenage children. The youngest daughter, thirteen-year-old Natasha (Natalia Ilyinichna), believes she is in love with Boris Drubetskóy, a disciplined young man who is about to enter the army as an officer. Twenty-year-old Nikolai Ilyich promises his love to his fifteen-year-old cousin, Sonia (Sofia Alexandrovna), an orphan who has grown up with the Rostov family. The eldest of the children of the Rostov family, Vera Ilyinicha is cold and somewhat arrogant, but with good prospects of marriage with a Russian-German officer, Adolf Karlovich Berg. Petya (Pyotr Ilyich), the youngest of nine years, like his older brother, is impetuous and wants to join the army when his age allows. The heads of the family, the Earl and Countess, are a loving couple, but always worried about their messy finances.

At Lýsyie Gory, the Bolkonsky estate, Prince Andrei goes off to war, leaving his pregnant wife Liza alone with her eccentric father, Prince Nikolai Andreevich Bolkonsky, and their devoted daughter, Maria Nikolaevna Bolkonskaya.

The second part begins with the description of the preparations for war between the Russian Empire and Napoleonic troops. At the Battle of Schöngrabern, Nikolai Rostov, recruited as an ensign in a squad of hussars, has his first combat experience in which he meets Prince Andrei, whom he insults in a fit of impetuousness. Nikolai is deeply attracted by the charisma of Tsar Alexander I, even more than the rest of the young soldiers. He plays and associates with his officer Vasily Dmitrich Denisov, and befriends the ruthless, and perhaps psychopathic Fyodor Ivanovich Dolokhov. Bolkonsky, Rostov and Denisov are involved in the disastrous Battle of Austerlitz, in which Andrei is wounded trying to salvage a Russian banner.

Second volume

The second book begins with the brief homecoming of Nikolai Rostov. He finds his family in financial ruin due to mismanagement of his estate. Nikolai spends an eventful winter at his house in the company of his friend Denisov, the officer of the Pavlogradsky hussar regiment whom he serves. Natasha has grown into a beautiful young woman, and Denisov falls in love with her. He proposes to her, but is rejected: his mother begs Nikolai to find for himself a good marriage prospect to help the family, but he does not agree to his request and promises to marry his childhood sweetheart, sonia.

Pierre Bezukhov, after receiving his large inheritance, goes from being a clumsy young man to being one of the richest and most eligible bachelors in the Russian Empire. He wants to marry the beautiful and immoral Hélène, daughter of Prince Kuragin (Elena Vasílyevna Kuragina), to whom he is superficially attracted, despite knowing that her decision is not correct. Hélène, who is rumored to be involved in an incestuous relationship with her brother, the equally charming and immoral Anatol, tells Pierre that she will never have children with him. It is also rumored that Hélène is having an affair with Dolokhov, who mocks Pierre in public. He then loses his temper and challenges Dolokhov, an experienced duelist and ruthless killer, to a duel. Unexpectedly, Pierre wounds Dolokhov. Hélène denies her affair, although Pierre is convinced of her guilt, and after behaving violently towards her, he leaves her. In the midst of his moral and spiritual confession, Pierre joins the Masonic society and is consequently involved in his internal politics and way of life. Much of this second volume deals with Pierre's spiritual passions and conflicts to become a better man. He abandons his former carefree demeanor of a rich aristocrat and enters into Tolstoy's particular philosophical journey: How to lead a morally acceptable life in an ethically imperfect world? The question continually baffles and confuses him. He tries to free and improve the lives of his servants, but ultimately fails to achieve any major achievements.

Pierre is a stark contrast to the intelligent and ambitious Prince Andrei Bolkonsky. During the Battle of Austerlitz, Andrei is inspired by a vision of glory in leading a charge as he sees his troops falling back, but suffers a near-fatal wound from artillery. Near death, Andrei realizes that all of his previous ambitions are meaningless in life and his former hero, Napoleon (who rescues him in a later reconnaissance on horseback from the battlefield), is apparently as vain as the same.

Prince Andrei recovers from his injuries in a military hospital and returns home to witness the death of his wife Liza in childbirth. The guilt of his own conscience weighs on him for not having treated her wife better when she was still alive, and it haunts him because of the sad expression on her face. His son Nikólienka manages to survive childbirth.

Overwhelmed by nihilistic disillusionment, Prince Andrei decides not to return to the army, preferring instead to remain on his estate working on a project on military behavior in order to solve the problems of disorganization responsible for the loss of so many lives in the Russian side during the conflict. Pierre visits him with new questions, where is God in this amoral world? He is intensely interested in pantheism and the possibility of an afterlife.

Pierre's wife, Hélène, begs him to return to her, and against her better judgment and Masonic law, he does. Despite her bland superficiality, Hélène establishes herself as an influential hostess in Petersburg society.

Prince Andrei feels the urge to bring his new military ideas to St. Petersburg, naively hoping to influence both the Emperor and those closest to him. Young Natasha, also in Saint Petersburg, finds herself caught up in the excitement of dressing for her first ball, where she will meet Prince Andrei whom she will impress with her vivacious charm. Andrei then believes that he has found a purpose in his life again and, after visiting the Rostovs several times, he proposes to Natasha. However, the old prince Bolkonsky, Andrei's father, advises against this marriage, since the Rostovs are not a family he likes, and insists that he delay the marriage for a year. Prince Andrei goes abroad to recover from his injuries, leaving Natasha in deep anguish. He will soon recover her spirits and Count Rostov will take her and Sonia to spend time in Moscow with a friend of hers.

Natasha visits the Moscow Opera, where she meets Hélène and her brother Anatol. Still married to a Polish woman who had left her native country, he feels strongly attracted to her Natasha: he decides to seduce her. Hélène and Anatol conspire together to carry out this plan. Anatol kisses Natasha and writes passionate letters to her, finally setting up a plan to elope together. Natasha is convinced that she loves Anatol so she writes to Princess Maria, Andrei's sister, breaking off her engagement. At the last moment, Sonia discovers her escape plans. Pierre is initially horrified by Natasha's behaviour, but realizes that he has a crush on her. When the Great Comet of 1811 streaks across the sky, life seems to start anew for Pierre.

Prince Andrei coolly accepts the break off of the engagement with Natasha. He tells Pierre that his pride will not allow him to renew his proposal. Ashamed, Natasha makes a suicide attempt and falls seriously ill.

Third volume

With the help of her family, especially Sonia, and the awakening of her religious faith, Natasha remains in Moscow during this difficult period. Meanwhile, the whole of Russia is affected by the confrontation between Napoleon's troops and the Russian army. Pierre convinces himself through gematria that Napoleon is the Antichrist of the Apocalypse. Old Prince Bolkonsky dies of a heart attack while trying to protect his property from French looters. There is no organized help from the Russian army for the Bolkonskys, but Nikolai Rostov shows up on his estate in time to put down an incipient peasant revolt. Nikolai is also attracted to Princess Maria, but remembers her promise to Sonia.

Back in Moscow, Petya manages to snatch a small piece of biscuit from the Tsar outside the Dormition Cathedral, eventually convincing his parents to allow him to enlist.

Napoleon is the main character of this part of the novel and is presented in great detail, both as a thinker and as a strategist. His clothing, as well as his habitual attitudes and mentality are meticulously depicted. He also describes the force of more than 400,000 French army men (although only 140,000 were French-speaking) marching swiftly through the Russian countryside in late summer, managing to reach the outskirts of the city of Smolensk. Pierre decides to leave Moscow and go to witness the Battle of Borodino from a viewpoint with a Russian artillery team. After observing the battle for a while, he begins to participate in it by carrying ammunition for the army. In the midst of the turmoil, he experiences firsthand the death and destruction of war. The battle turns into a horrible slaughter for both armies and ends in a dead end. The Russians, however, have won a moral victory defending themselves against Napoleon's supposedly invincible army. For strategic reasons and because of its heavy losses, the Russian army withdrew the next day. Among the victims are Anatol Kuragin and Prince Andrei. Anatol loses a leg and Andrei suffers a serious wound to the abdomen from a grenade. Both are declared dead, but the families will not receive notification because of the prevailing disorder.

The Rostovs have waited until the last minute to leave Moscow, even knowing that Kutuzov has retreated beyond Moscow. Muscovites receive conflicting orders, often of a propaganda nature, either in the form of fleeing or fighting. Count Fiódor Rostopchín publishes posters that exhort the population to fight with pitchforks if necessary. Before fleeing, Rostopchin gives the order to set fire to some buildings in the city, although the Moscow fire of 1812 had other causes, as Tolstoy recounts in the novel. The Rostovs must decide what to take with them on their escape from Moscow, but in the end, Natasha convinces them to load the wagons with wounded from the Battle of Borodino. Prince Andrei is among these wounded, although Natasha will not be aware of this until later.

When Napoleon's great army finally occupies an abandoned and burned-out Moscow, Pierre decides to carry out a quixotic mission: assassinate Napoleon. He becomes an anonymous man within all the chaos, giving up his responsibilities as a nobleman and dressing like a peasant, while rejecting his former duties and lifestyle. The only people he sees while dressed in such a way are Natasha and part of her family as they leave Moscow. Natasha recognizes him and smiles at him, and he, in turn, realizes the extent of her love for her.

Pierre saves the life of a French officer who fought at Borodino, but is taken prisoner by retreating Frenchmen during their assassination attempt on Napoleon, after saving a woman from being raped by soldiers of the French army.

Fourth volume

Pierre befriends a fellow prisoner, Plato Karataev, a peasant with the demeanor of a saint, who is incapable of doing evil. Pierre finally finds in Karataev what he was looking for: a completely honest person (unlike the aristocrats of St. Petersburg society), who is totally unpretentious. Pierre discovers the meaning of life simply by living and interacting with Karataev. After witnessing the sack of Moscow and the shooting of Russian civilians by French soldiers, Pierre is forced to march with the great French army during their disastrous retreat from Moscow in the harsh and cold Russian winter. After months of trials and tribulations—during which Karataev is shot and wounded by a French soldier—Pierre is freed by a Russian Empire raiding party after a minor skirmish with French troops. During this contest the young Petya will perish.

Meanwhile, Andrei, wounded during the Napoleonic invasion, stumbles upon the Rostov family, who will care for him as they flee Moscow to Yaroslavl. He meets with Natasha and her sister Maria de ella before the end of the war. Having lost all will to live, he forgives Natasha in his last moment before dying.

As the novel draws to a close, Pierre's wife, Hélène, dies of an overdose of abortion medication (Tolstoy does not state this explicitly, the euphemism he uses being somewhat ambiguous). Pierre reunites with Natasha, while victorious Russia rebuilds Moscow. Natasha talks about the death of Andrei and Pierre de Karataev. Both are aware of a growing bond between them. With the help of Princess Maria, Pierre finds love and, freed by the death of his ex-wife, marries Natasha.

Afterword in two parts

The first part of the epilogue begins with the wedding of Pierre and Natasha in 1813. It is the last happy event for the Rostov family, which is going through a period of transition. Count Rostov passed away soon after, leaving his eldest son Nikolai in charge of the indebted estate.

Nikolai finds himself with the task of supporting the family on the brink of bankruptcy. His aversion to the idea of marrying for wealth nearly gets in his way, but he eventually marries Princess Maria Bolskónskaya, thereby saving his family from financial ruin.

Nikolái and Maria move to Lýsyie Gory with their mother and Sonia, whom they will support for the rest of their lives. Thanks to his wife's fortune, Nikolai pays off all his family's debts. They also take in Prince Andrei's orphaned son, Nikolai Andreevich (Nikólienka) Bolskonsy.

As in any good marriage, there are misunderstandings, but both Pierre and Natasha and Nikolai and Maria remain faithful and attentive to their spouses. Pierre and Natasha visit Lýsyie Gory in 1820, to the jubilation of all concerned. There are hints in this part of the novel that both Pierre and the young idealist Nikolienka will be part of the Decembrist revolt. The first epilogue concludes that Nikolienka vows to carry out an action that even his late father would be pleased with (presumably as a revolutionary in the Decembrist revolt).

The second part of the epilogue is Tolstoy's critique of all existing forms of conventional History. While the great man theory claims that historical events are the result of the actions of "heroes" and other great people, Tolstoy claims that this is impossible, due to the infrequentity with which these actions result in great historical events.. Rather, according to Tolstoy, great historical events are the result of many small acts driven by the thousands of people who participate in them (he likens this to calculus, and the addition of infinitesimals). He then argues that these smaller events are the result of an inverse relationship between necessity and free will. Necessity is based on reason and therefore it is explicable through historical analysis and free will that it is based on consciousness, and therefore is inherently unpredictable.

Reception

The novel that made its author "the true lion of Russian literature" (according to Ivan Goncharov) was a huge success with the reading public upon publication, generating dozens of reviews and analytical essays, some of which (by Dmitry Pisarev, Pavel Annenkov, Mikhail Dragomirov, and Nikolai Strakhov) formed the basis for later Tolstoy scholars' research. However, the initial response of the Russian press to the novel was muted, most critics could not decide how to classify it. The liberal newspaper Golos (La Voz, April 3, no. 93, 1865) was one of the first to react. Its anonymous reviewer posed a question that was later echoed by many others: “What could this be? What kind of genre are we supposed to archive it to? [...] Where is the fiction and where is the real story?».

The writer and critic Nikolai Akhsharumov, writing in Vsemirny Trud (#6, 1867) suggested that War and Peace was "neither a chronicle nor a historical novel", but a genre fusion, this ambiguity never undermines its immense value. Annenkov, who also praised the novel, was equally vague when he tried to classify it. "It was his suggestion the cultural history of a large part of our society, the political and social panorama of it at the beginning of the current century." "It is the [social] epic, the historical novel and the vast picture of the life of the whole nation," wrote Ivan Turgenev in his attempt to define War and Peace in the preface to his French translation from The Two Hussars (published in Paris by Le Temps in 1875).

In general, the literary left received the novel coldly. They saw him as devoid of social criticism and enthusiastic about the idea of national unity. They saw its greatest flaw as the author's "inability to portray a new type of revolutionary intelligentsia in his novel", as critic Varfoloméi Záytsev put it. Articles by Dmitri Mináyev, Vasili Bervi-Flerovsky and Nikolai Shelgunov in the magazine Delo characterized the novel as "devoid of realism", showing its characters as "cruel and rude", "mentally stoned", "morally depraved" and promoting "the philosophy of stagnation." Even so, Mikhail Saltykov-Shchedrin, who never publicly expressed his opinion of the novel, was reported in a private conversation to express his delight at "how strongly this count has stung our higher society". Dmitri Pisarev in his unfinished article "The Old Russian Nobility" ("Stároye barstvo", Otéchestvennye Zapiski, #2, 1868), although he praised Tolstoy's realism in portraying members of high society, he was still unhappy with the way the author, as he saw it, "idealized" the old nobility, expressing "unconscious and quite natural tenderness towards" the Russian dvoryanstvo (nobility of Russia). On the opposite front, the conservative press and "patriotic" authors (among them Avraam Norov and Pyotr Vyazemsky, both participants in the war) were accusing Tolstoy of knowingly distorting the history of 1812, desecrating the "patriotic sentiments of our fathers." and ridiculing the dvoryanstvo.

One of the first full-length articles on the novel was by Pavel Annenkov, published in the 1868 issue 2 of Vestnik Evropy (Messenger from Europe). The critic praised Tolstoy's masterful portrayal of man in war, marveled at the complexity of the entire composition, organically merging historical fact and fiction. "The dazzling side of the novel," according to Annenkov, was "the natural simplicity with which [the author] transports mundane affairs and great social events down to the level of a character witnessing them." Annenkov thought that the novel's historical gallery was incomplete with the two "great raznochintsy" (en:raznochintsy), Speransky and Arakcheev, and deplored the fact that the author stopped presenting the novel " this relatively crude but original element. In the end, the critic called the novel "the entire era of Russian fiction."

The Slavophiles declared Tolstoy their bogatyr and declared War and Peace “the Bible of the new national idea”. Several articles on War and Peace were published in 1869-1870 in the magazine Zaryá by Nikolai Strakhov. " War and Peace is a work of genius, equal to everything Russian literature has produced before", he pronounced himself in the first, smaller essay. “Now it is quite clear that since 1868, when War and Peace was published, the very essence of what we call Russian literature has become quite different, acquired a new form and meaning,” continued the critic later. Strakhov was the first critic in Russia who declared Tolstoy's novel a masterpiece of a previously unknown level in Russian literature. Even so, being a true Slavophile, he could not help but see the novel as promoting the main Slavophilic ideas of "the supremacy of the meek Russian character over the rapacious European type" (using Apollon Grigoriev's formula). Years later, in 1878, discussing Strakhov's own book The World as a Whole, Tolstoy criticized both Grigoriev's concept (of "Russian meekness versus Western bestiality") like Strakhov's interpretation.

Reviewers included military officers and authors specializing in war literature. Most highly rated the wit and realism of Tolstoy's battle scenes. N. Lachinov, a staff member of the newspaper Russki Invalid (No. 69, April 10, 1868) described the scenes of the battle of Schöngrabern as "with the highest degree of historical and artistic truth." » and fully agreed with the author's opinion about the Borodino battle, which some of his opponents disputed. Army general and respected military writer Mikhail Dragomirov, in an article published in Oruzheiny Sbórnik (The Military Almanac, 1868-1870), while disputing some of Tolstoy's ideas on the "spontaneity" of wars and the role of the commander in battles, he advised all Russian army officers to use War and Peace as a stationery book, describing its battle scenes as "incomparable" and "serving for an ideal manual for every textbook on theories of military art."

Unlike professional literary critics, the leading Russian writers of the time wholeheartedly supported the novel. Goncharov, Turgenev, Leskov, Dostoevsky and Fet have gone on record declaring War and Peace to be the masterpiece of Russian literature. Ivan Goncharov, in a letter of 17 July 1878 to Piotr Ganzen, advised him to choose to translate War and Peace into the Danish language, adding: "This is positively what might be called a Russian Iliad. Embracing the whole era, it is the grandiose literary event, showcasing the gallery of great men painted by a lively brush of the great master [...] This is one of the most profound literary works, if not the most profound». In 1879, dissatisfied with the fact that Ganzen chose Anna Karenina to begin with, Goncharov insisted: "War and Peace is the extraordinary poem of a novel, both in content and in action. It also serves as a monument to the glorious era in Russian history when any figure you pick up turns out to be a colossus, a bronze statue. Even the minor characters [in the novel] have all the characteristic features of the Russian people and their life." In 1885, expressing his satisfaction that Tolstoy's works had already been translated into Danish, Goncharov once again emphasized the immense importance of War and Peace. "Count Tolstoy really stands out from everyone else here [in Russia]," he commented.

Fyodor Dostoyevsky (in a letter to Strakhov dated May 30, 1871) described War and Peace as "the last word in landlord literature and the most brilliant". In a draft version of The Adolescent , he described Tolstoy as "a historiographer of the dvoryanstvo , or rather, its cultural elite". "Objectivity and realism impart a marvelous charm to all scenes, and alongside persons of talent, honor, and duty expose numerous scoundrels, thugs, and worthless fools," he added. In 1876, Dostoevsky wrote: "My strong conviction is that a writer of fiction must have the deepest knowledge, not only of the poetic side of his art, but also of the reality with which he deals, both in its historical and contemporary context. Here [in Russia], as far as I can see, only one writer excels at this, Count Lev Tolstoy."

Nikolai Leskov, then an anonymous critic at Birzhevoy Vestnik (Stock Exchange News), wrote several articles highly praising War and Peace, calling it "the best Russian historical novel" and "the pride of contemporary literature." Marveling at the realism and factual truth of Tolstoy's book, Leskov thought that the author deserved special credit for "having lifted the spirits of the people on the high pedestal that he deserved." "While working more elaborately on individual characters, the author has apparently been more diligently studying the character of the nation as a whole; the lives of the people whose moral force was concentrated in the army that arose to fight against the mighty Napoleon. In this regard, Count Tolstoy's novel could be seen as "an epic of the Great National War that has hitherto had its historians but never had its singers," Leskov wrote.

Afanasi Fet, in a letter to Tolstoy on January 1, 1870, expressed his great delight in the novel. "You have managed to show us in great detail the other mundane side of life and explain how it organically feeds the external and heroic side," he added.

Ivan Turgenev gradually reconsidered his initial skepticism regarding the novel's historical aspect and also Tolstoy's style of psychological analysis. In his 1880 article written in the form of a letter to Edmond Abou, editor of the French newspaper Le XIXe Siècle, Turgenev described Tolstoy as "the most popular Russian writer and War and Peace as "one of the most remarkable books of our age." «This vast work has the spirit of an epic, where the life of Russia of the beginning of our century in general and in detail has been recreated by the hand of a true master [...] The way in which Count Tolstoy carries out out his treatise is innovative and original. This is the great work of a great writer, and in it there is a true and true Russia," Turgenev wrote. It was largely due to Turgenev's efforts that the novel began to gain popularity among European readers. The first French edition of War and Peace (1879) paved the way for the worldwide success of Leo Tolstoy and his works.

Since then, many world-famous authors have hailed War and Peace as a masterpiece of world literature. Gustave Flaubert expressed his delight in a January 1880 letter to Turgenev, writing: "This is first-class work! What an artist and what a psychologist! The first two volumes are exquisite. He used to shout with joy while reading. This is powerful, very powerful indeed." John Galsworthy later called War and Peace "the greatest novel ever written." Romain Rolland, recalling reading his novel as a student, wrote: "This work, like life itself, has no beginning or end. It is life itself in its eternal movement. Thomas Mann thought War and Peace was "The greatest war novel in the history of literature." Ernest Hemingway confessed that it was from Tolstoy that he had been learning how to "write about war in the most direct, honest, objective, and crude way." "I don't know of anyone who can write about war better than Tolstoy," Hemingway stated in his 1955 Men at War The Greatest Anthology War Stories of All Time.

Isaak Bábel said, after reading War and Peace: «If the world could write alone, it would write like Tolstoy». Tolstoy "gives us a unique combination of "naive objectivity" of the oral narrator with the interest in detail characteristic of realism. This is the reason for our confidence in presenting him ».

Main characters

- Pierre Bezújov

- Natasha Rostova

- Andréi Bolkonsky

- María Bolkónskaya

- Nikolái Rostov

- Napoleon Bonaparte

- Mikhail Kutúzov

- Elena Kuráguina

- Anatol Kuraguin

- Anna Pávlovna.

Many of Tolstoy's characters were based on real people he knew. For example, Nikolai Rostov and Maria Bolkonskaya are a reflection of Tolstoy's memories of his parents, while Natasha is a mix of his wife and his sister-in-law. Pierre and Prince Andrei have traits of the author's personality, while many autobiographical data are used in the story of both characters.

Meaning of unusual words

- Húsar: cavalry soldier dressed in the Hungarian.

- Ulano: in the Austrian, German and Russian armies, soldier of light cavalry armed with spear.

- Izbá: wooden house.

- Verstá: Russian linear measure, equivalent to 1067 meters.

- Mir (community): rural community at the time of tsarist.

- Troika: in the novel, sled by three horses arranged side by side.

Direct translations from Russian to Spanish

- War and peace. Translation: Joaquín Fernández-Valdés. Barcelona: Alba Editorial. 2021.

- War and peace. Translation: Gala Arias Rubio (the novel's historian, non-canonical edition). Barcelona: Mondadori. 2004.

- War and peace. Translation: Lydia Kúper (correction of the translation of José Laín Entralgo and José Alcántara). Madrid: Mario Muchnik Workshop. 2003.

- War and peace. Translation: José Laín Entralgo and José Alcántara. Barcelona: Planet. 1979.

- War and peace. Translation: Irene and Laura Andresco. Madrid: Aguilar. 1955-56.

Stage and film adaptations

- War and peace, opera in two parts composed of Serguéi Prokófiev.

- War and peace, 1956 film directed by King Vidor, with the performance of Henry Fonda, Audrey Hepburn, Mel Ferrer, John Mills, Vittorio Gassman, Anita Ekberg, Herbert Lom, and Fernando Aguirre, among others.

- War and peace, 1967 film directed by Serguéi Bondarchuk.

- War and peace, BBC television series of 1972 starring Anthony Hopkins.

- War and peace, mini-series of 2007 starring Clémence Poésy and Alessio Boni.

- War and Peace, 2016 BBC TV miniserie starring Paul Dano, Lily James and James Norton.

- Natasha, Pierre and the Great Comet of 18122016 Broadway musical. It narrates the events of the second volume. Music and letters from Dave Malloy.

- War " Love, theatrical work of 2022 written by Carlos Be.

Contenido relacionado

Digital world

Doris Lessing

Juan Carlos Onetti