Vulgate

The Vulgate (Bible Vulgate in Latin; Βουλγάτα or Βουλγκάτα in Greek) is a translation of the Bible into Latin, made in late IV century (from AD 382) by Jerome of Estridon.

It was commissioned by Pope Damasus I (366-384) two years before his death. The version takes its name from the phrase vulgata editio (disclosed edition) and was written in ordinary Latin as opposed to Cicero's classical Latin, which Jerome of Estridón dominated. The goal of the Vulgate was to be easier to understand and more accurate than its predecessors.

The Latin Bible used before the Vulgate, the Vetus Latina, was not translated by a single person or institution and was not even uniformly edited. The quality and style of individual books varied. The Old Testament translations came almost all from the Greek Septuagint.

In the IV century, the Johannine comma (Latin, comma johanneum), as a gloss on the verses of the First Epistle of John 5, 7-8, and was later added to the text of the epistle, in the Latin Vulgate, about the year 800.

Relation to the ancient Latin Bible

Latin Biblical texts in use before Jerome's Vulgate are often collectively referred to as the Vetus Latina, or "Old Latin Bible"; where "Old Latin" it means that they are older than the Vulgate and are written in Latin, not that they are written in Old Latin.

Jerome himself uses the term "Latin Vulgate" for the "Vetus Latina" text, intended to denote this version as the common Latin representation of the Greek Vulgate or common Septuagint (which Jerome otherwise calls the 'Seventy version' #39;); and this remained the usual use of the term "Latin Vulgate" in the West for centuries. Jerome reserves the term "Septuagint" (Latin for seventy) to refer to the Hexapla Septuagint. The first known use of the term Vulgate to describe the "new" Latin translation was Roger Bacon in the 13th century.

Translations in Vetus Latina had accumulated piecemeal over a century or more, were not translated by any one person or institution, nor were they uniformly edited. Individual books varied in translation quality and style, and different manuscripts and citations attest to wide variations in readings. Some books appear to have been translated multiple times; the book of Psalms, in particular, circulated for over a century in an earlier Latin version (the Cypriot version) before it was superseded by the Old Latin version in the IV. Jerome, in his preface to the Vulgate Gospels, commented that there were "as many translations as there were manuscripts." The base text for Jerome's revision of the gospels was an ancient Latin text similar to Codex Veronensis. For the text of the Gospel of John, the Codex Corbiensis was used as a source.

The translation

Pope Damasus had instructed Jerome to be conservative in his revision of the old Latin gospels. It is possible to see the obedience of St. Jerome to this mandate of the preservation in the Vetus Latina of the variant of the Latin vocabulary for the same Greek terms. Therefore, "summum priest" becomes "princeps sacerdotum" in the Vulgate in Matthew; as "summus sacerdos" in the Vulgate in Mark; and as "pontiff" in the Vulgate in John. The Vetus Latina gospels had been translated from Greek originals of the Western text type, yet most showed little agreement between translations. Comparison of the texts of the Gospel of Jerome with those of the ancient Latin texts, suggests that his revision focused substantially on redacting his "Western" phraseology. enlarged according to the Greek texts of the best early Byzantine and Alexandrian witnesses.

An important change introduced by Jerome was to rearrange the Latin gospels. The ancient Latin gospel books generally followed the "Order of the West": Matthew, John, Luke, Mark; where Jerome adopted the "Greek Order": Matthew, Mark, Luke, John. It seems that he followed this order in his work schedule; as revisions of it become progressively less frequent and less consistent in the gospels, presumably made later. In places, Jerome adopted readings that did not correspond to a direct interpretation of the Old Latin or Greek text, reflecting a particular doctrinal interpretation; as in his new version of panem nostrum supersubstantialem in Matthew 6:11.

The unknown reviewer of the rest of the New Testament shows marked differences with Jerome, both in editorial practice and in his sources. Where Jerome sought to correct the old Latin text by reference to the best recent Greek manuscripts, with a preference for those that conform to the Byzantine text type, the Greek text underlying the revision of the rest of the New Testament demonstrates the Alexandrian text type, found in mid-century IV large uncials, more similar to Codex Sinaiticus. The reviser's changes generally conform very closely to this Greek text, including in matters such as word order; as long as the resulting text is barely intelligible as Latin.

After the gospels, the most used and copied part of the Christian Bible is the Book of Psalms; and accordingly Damasus also commissioned St. Jerome to revise the psalter in use at Rome, so that it would agree with the Greek of the common Septuagint. This he did tirelessly when he was in Rome; but he later repudiated this version, arguing that the copyists had reintroduced erroneous readings. Until the 20th century, the surviving Roman Psalter was commonly assumed to represent Jerome's first attempted revision; but a more recent version, after Bruyne, rejects this identification. The Roman Psalter is, in fact, one of at least five revised versions of the Old Latin Psalter from the mid-century IV but, compared to the other four, the revisions in the "Roman Psalter" they are in clumsy Latin, and significantly fail to follow the known translation principles of Jerome, especially with regard to correcting harmonized readings. However, it is clear from Jerome's correspondence (especially in his defense of the "Gallican Psalter" in the long and detailed Epistle n106) that he was familiar with the text of the "Roman Psalter." 3. 4;; and consequently this revision is supposed to represent the Roman text as Jerome had found it.

Jerome's first efforts at translation, his revision of the four gospels, were devoted to Damasus; but after the death of Pope Damasus, Jerome's versions had little or no official recognition. Jerome's translated texts had to make their way on their own merits. The Old Latin versions continued to be copied and used alongside the Vulgate versions. Commentators such as Isidore of Seville and Gregory the Great (pope from 590 to 604) recognized the superiority of the new version and promoted it in their works; but the old ones tended to continue in liturgical use, especially the Psalter and Biblical Canticles. In the prologue to Moralia in Job, Gregorio Magno writes: "I comment on the new translation. But when argumentation is necessary, he sometimes uses the evidence of the new translation, sometimes of the old one, from the Apostolic See, which by the grace of God I preside, uses both & # 34;. This distinction of "new translation" and "old translation" it is found regularly in commentators up to the 8th century century; but it remained uncertain for those books which had not been revised by Jerome (the New Testament outside the Gospels, and some of the deuterocanonical books), which versions of the text belonged to the "new" translation and which to the "old one". The oldest biblical manuscript where all the books are included in the versions that would later be recognized as "Vulgate" it is the Codex Amiatinus of the VIII century; but as late as the 12th century, the Vulgate Codex Gigas preserved an ancient Latin text for Revelation and the Acts of the Apostles.

Changes in familiar phrases and expressions aroused hostility in congregations, especially in North Africa and Hispania; while scholars often tried to adapt Vulgate texts to Old Latin patristic citations; and consequently many Vulgate texts became contaminated with Old Latin readings, reintroduced by copyists. Spanish Biblical traditions, with many Old Latin borrowings, were influential in Ireland, while Irish and Spanish influences are found in Vulgate texts in northern France. In contrast, in Italy and southern France a much purer Vulgate text prevailed; and this is the version of the Bible that was established in England after the mission of Augustine of Canterbury.

Influence on the West

For more than a thousand years (c. 400 to 1530), the Vulgate was the definitive edition of the most influential text in Western European society. In fact, for most Western Christians, it was the only version of the Bible ever found. The influence of the Vulgate throughout the Middle Ages and the Renaissance at the beginning of the first modern age; for Christians in these times, the phraseology and wording of the Vulgate permeated all areas of culture. Aside from its use in prayer, liturgy, and private study, the Vulgate inspired ecclesiastical art and architecture, hymns, countless paintings, and theatrical mysteries.

The Protestant Reformation

While the Geneva Reformed (Calvinist) tradition sought to introduce translated vernacular versions of the original languages, it maintained and extended the use of the Vulgate in theological debate. In both John Calvin's published Latin sermons and Theodore Beza's Greek editions of the New Testament, the accompanying Latin reference text is the Vulgate; and where Protestant churches took their lead from the example of Geneva, as in England and Scotland, the result was a broader appreciation of St. Jerome's translation in its dignified style and flowing prose. The nearest equivalent in English, the King James Version or Authorized Version, shows marked Vulgate influence, especially in comparison with William Tyndale's earlier vernacular version, with regard to St. Jerome's demonstration of how one can combine a technically accurate Latinized religious vocabulary. Dignified prose and vigorous poetic rhythms.

The Vulgate continued to be regarded as the standard scholarly Bible for most of the 17th century century. Walgl's London Polyglot of 1657 completely ignores the English language. Walton's reference text is the Vulgate. The Latin Vulgate is also found as the standard text of Thomas Hobbes' writing Leviathan of 1651, indeed Hobbes gives Vulgate verse and chapter numbers (for example, Job 41:24, Job 41:33) for its main text.

The Council of Trent

The Council of Trent (1545-1563) gave the Vulgate official status as the touchstone of the biblical canon regarding which parts of the books are canonical. [58] When the council listed the books included in the canon, it qualified the books as "complete with all their parts, as they have been used to be read in the Catholic Church, and as they are contained in the old Latin edition. vulgate". The fourth session of the Council specified 72 canonical books in the Bible: 45 in the Old Testament, 27 in the New Testament; Lamentations are not counted as separate from Jeremiah. [59] On June 2, 1927, Pope Pius XI clarified this decree, allowing the Coma Johanneum to be open to dispute, and there were further clarifications with the Divino afflante Spiritu of Pope Pius XII.

Translations and editions

Prior to the publication of Pius XII's Divino afflante Spiritu, the Vulgate was the source text used for many vernacular translations of the Bible. In English, the interlinear translation of the Lindisfarne Gospels, as well as other Old English translations of the Bible, the John Wycliffe translation, the Douay-Rheims Bible, the Confraternity Bible, and the Knox Bible were made from the Vulgate..

In Spanish, the Alfonsina Bible, The Gospels of Father Anselmo Petite, the Scio Bible, the Torres Amat Bible and the Bible of Vence stand out.

Conservation

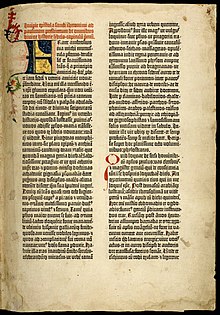

A number of early manuscripts containing or reflecting the Vulgate survive today. Dating to the 8th century century, the Codex Amiatinus is the oldest complete manuscript. The Fuldensis codex, which dates from about 545, is earlier, although the gospels are a corrected version of the Codex Diatessaron.

In the Middle Ages the Vulgate succumbed to the inevitable changes wrought by human error, in the countless copying of the text in monasteries across Europe. From its earliest days, the Vetus Latina readings were introduced. The marginal notes were erroneously interpolated in the text. No copy was the same as another. About the year 550 Cassiodorus made the first attempt to restore the Vulgate to its original purity. Alcuin of York supervised efforts to copy a restored Vulgate, which he presented to Charlemagne in 801. Similar attempts were repeated by Theodulf, Bishop of Orleans (787? - 821); Lanfranc, Archbishop of Canterbury (1070-1089); Saint Stephen Harding, the Cistercian Abbot (1109-1134), and Deacon Nicholas Maniacoria (early 13th century).

The Vulgate and other later editions

Although the advent of the printing press greatly reduced the potential for human error and increased the consistency and uniformity of the text, the earliest editions of the Vulgate simply reproduced manuscripts that were readily available to publishers. Of the hundreds of editions, the most notable is that of Mazarin, published by Johann Gutenberg in 1455, famous for its beauty and antiquity.

- In 1504 the first Vulgate with reading variants was published in Paris.

- One of the texts of the Complutense Polyglot Bible was an edition of the Vulgate, made with the ancient and corrected manuscripts to agree with the Greek.

- Erasmus of Rotterdam published a corrected edition with the Greek and Hebrew in 1519, in addition to editions of the New Testament in Greek with the Latin Vulgate, being only the editions of 1516 and 1527, the latter included the Latin Vulgate of Jerome with the corrected edition of Erasmus and the Greek text.

- A new edition of the Latin Bible made in 1528 by Santes Pagnino called Veteris et Novi Testamenti nova translatio, commissioned by Pope Leo X, being used by many for their impressive Hebrew translation.

- Robertus Stephanus would publish several editions of the Vulgata, with comments by François Vetable and another with illustrations. It would then perform a critical version of the Latin-language Bible, mainly using the New Testament of Theodore of Beza and the translation of the Old Testament of Santes Pagnino.

- The Latin Bible of Louvain critical edition of John Hentenius of Lovain in 1547, which became the standard before the Sistine Vulgate.

- Vatablo Bible, being this a double edition with the vulgata of San Jerónimo with a corrected version of the edition of santes Pagnino, made by the professors of the University of Salamanca.

- The Nova Vulgata is the official Latin edition of the Bible published by the Holy See for use in the contemporary Roman Rite. It is not a critical edition of the historic Vulgate of San Jerónimo, but a revision of the text intended to conform to the modern critical texts of Hebrew and Greek and produce a style closer to the classic Latin. Consequently, it introduces many readings that are not supported in any old manuscript of the Vulgate; but that provide a more accurate translation of texts in original languages to Latin.

- The Sacra Vulgate Bible of the biblical society of Stuttgart, a critical edition that seeks to rebuild the original of St.

Contenido relacionado

Ganges

Muhammad

Mercury (mythology)