Voynich manuscript

The Vynich manuscript is an illustrated book, of unknown contents, written by an anonymous author in an unidentified alphabet and an incomprehensible language. It was named after the antique book dealer Wilfrid M. Voynich (1865-1930), who purchased it in 1912. It is currently held at the Yale University Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library as MS 408.

Carbon 14 dating has determined that the parchment on which it is written was made between 1404 and 1438. Stylistic analysis of both the writing and the illustrations have corroborated its origin in the XV and origin from some Central European country, possibly Germany or northern Italy. Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II (1555-1612) is believed to have paid 600 gold ducats for it, although no record of such an operation exists, and it is certain that the manuscript passed to one of his advisers, the physician and pharmacist Jacobus de Tepenec, whose signature is faintly visible on the first folio. Since then it was in various hands until it ended up in the library of the Roman College. There it remained for more than two centuries, when in 1912 the collection that included it was acquired by Wilfrid Voynich.

The manuscript currently consists of about 240 pages, some of them folding sheets of various sizes. The illustrations that populate most of the pages include plants and herbs, pharmaceutical containers, astronomical and zodiacal diagrams, and bizarre systems of pipes and bathtubs populated by nude female figures. The "language" in which it is written, called Voynichese, obeys Zipf's Law just like other human languages, but it is distinguished from most of them by an abnormally low entropy, the effect of a set of regularities that make the combination between the characters are very predictable.

The Voynich manuscript has been studied by many professional, linguist, and amateur cryptographers, including American and British codebreakers of World War I and World War II. Suggested hypotheses range from an unknown language or dialect, some fancy encryption, or a mindless hoax. None of the many claimed solutions have been independently verified and the manuscript remains undeciphered. The mystery of its meaning and origin has excited the popular imagination, turning it into an object of study and speculation.

Codicology

Overview

The Voynich manuscript is a vellum codex 225 x 160 mm and 5 cm thick. It has a cover made of goatskin parchment dating from the 18th-19th centuries, most likely placed by the Jesuits of the College Romano de Roma replacing an earlier cover. Indications, such as wormholes, suggest that the original binding was made of wood and covered with a tanned leather. Leather straps were added in the 1960s to stabilize the union and they were glued on top of the old ones, perhaps original ones, made with some type of fiber.

The clerk wrote on a carefully prepared vellum, although certain defects such as concave contours, holes (some of them sewn), and stretch marks are visible. Microscopic analyzes in 2009 and multispectral images taken in 2014 concluded that there are no signs of erasure of earlier writing, so the manuscript cannot be a palimpsest.

The manuscript currently consists of 102 folios arranged into 18 folios. Several bifolios are larger than usual, with additional folds and therefore more than the usual four pages, and are known as "fold-outs". These foldouts have different dimensions, with widths of the corresponding bifolios ranging from three to five pages (instead of two). In addition, there is a bifolio of about 45 x 45 cm that has an additional horizontal fold.

Each folio has a folio number in the upper right corner, numbered from 1 to 116, while the quire marks are always numbered in the lower right corner of the back of the last folio of each booklet, except in the quires 9 and 20, and are indicated with an Arabic numeral followed by a 9 for Latin -us and sometimes an 'm' between them. It is certain that the folio numbers and quire numbers were added by different people, between the 15th and 16th-17th centuries, and before several folios and quires went astray.

- Images

Missing pages

A total of 14 folios are missing from the manuscript: three bifolios (ff. 59-64) that should have been in the center of quire 8, two (ff. 109-110) that were in the center of quire 20, two more (ff. 91-92 and 97-98) that constituted, respectively, quires 16 and 18 and, lastly, two individual pages that were torn out after binding (ff. 12 and 74). The holes in the numbering of the pages and booklets indicate that it was added when the missing pages were still available.

The actual order of the manuscript

There are strong reasons to believe that the current order of folios and quires is different from the original order, including:

- Folios corresponding to different sections of the manuscript seem mixed. For example, the three bifolios in the pharmaceutical section are distributed in two separate kires (15 and 19).

- Bifolios of the herbal section with a different calligraphy and different text statistics are distributed arbitrarily, as if not intentional.

- In the biological section, the bifolio that consists of the 78v and 81r folios together form an integrated design with water flowing from one folio to the other, but this could only be visible if the original foliation was different from the current one.

- Glen Claston has noted that the biological section could contain two different themes and should therefore have formed two separate quires instead of one.

- The numbering mark of quire 9 is not in the usual place and there appear to be sewing spaces of an earlier binding on one of the folds dropdowns. Assuming that this should have been the original binding fold, the quire number would fall in its right place.

Reconstruction of his codicological history

René Zandbergen has suggested a tentative reconstruction of the codicological history of the manuscript:

- All the bifolios were prepared, first drawing the outlines of the illustrations and then adding the text.

- The planned order of the bifolios was somehow altered.

- First the notebooks were listed and then the folios. There could be a first binding here.

- The manuscript was removed from its binding and the painting was added. In this process six bifolios were lost.

- Some time later, folios 12 and 74 were cut.

History and owners of the manuscript

Early history: time and place of composition

In 2009, radiocarbon dating analysis of four samples of the manuscript (from folios 8, 26, 47, and 68) revealed that the parchment it was written on dated between 1404 and 1438 with a 95% probability. This definitively invalidates the theory, held by early Voynich researchers and later dismissed, that its author was the English scientist Roger Bacon, who died in 1294. Its provenance from the first half of the century XV had already been noted by renowned art historian Erwin Panofsky based on an analysis of the illustrations. Panofsky, according to a letter written by Ethel Voynich around 1932, also thought that it had been written in the “southwestern corner of Europe: Spain, Portugal, Catalonia or Provence; but most likely in Spain" and detected certain Judeo-Arabic and Dutch influences. However, when questioned again in 1954, his answer was that the manuscript was produced in Germany. In favor of the theory of German provenance is the representation of the zodiac cycle, with similar illustrations that can be traced in German manuscripts from the XV century, and the so-called "strange writing" (annotations made in Latin characters, although most likely from a later owner). On the other hand, a modern historian of botany, Sergio Toresella, recognizes an Italian style in calligraphy and herb drawings, an opinion also shared by the historian Alain Touwaide. In favor of Italian influence, the castle with swallow battlements, or Ghibellines, drawn on the so-called "rosette page" of the manuscript, is used. This architectural style dominates northern Italy and is associated with the Scaliger family, in the region around Verona, since the 14th century onwards. Both provenance theories are not necessarily exclusive. For René Zandbergen, the origin of the manuscript could well be described as "Alpine", with a mixture of Italian and German influences. Beinecke's catalog merely notes that it was written in Central Europe.

The purchase by Rudolf II

The scientist Johannes Marcus Marci, in a letter dated 1665 and which will be discussed later, indicates that Emperor Rudolf II of Habsburg bought the manuscript for a sum of 600 ducats. This information had been obtained from Raphael Mnišovský, a character interested in alchemy and secret writing who was a teacher of the future Emperor Ferdinand of Habsburg. No record of this transaction has been found in the summary ledgers of Rudolf II's court accounts. Claims that John Dee or his associate Edward Kelley are the sellers of the manuscript must be dismissed as Wilfrid Voynich's fanciful quip, without any factual foundation. In any case, it is possible that the monetary sum mentioned by Marci was paid for a largest set of books, among which the Voynich manuscript could have been included.

Jacobus of Tepenec

The first certain owner of the manuscript is the chemist and pharmacist Jacobus Horčický from Tepenec. In 1608 Jacobus cured Rudolf II of a serious illness and Rudolf II, in reward, elevated him to the minor nobility and allowed him to call himself "from Tepenec". His signature in the lower margin of the first folio has faded and is only visible under ultraviolet light, but it must date from after his ennoblement. Perhaps the manuscript was given to him in the hope that he would be able to decipher it, or perhaps he decided to take it for his account as payment of the substantial debt the emperor owed him. On his death, in 1622, Jacobus left all his belongings to the Jesuits in Prague and Melnik, but by then it appears that the manuscript was no longer in his hands.

George Barschius

A letter from George Barschius, dated April 21, 1639, reveals that he was in fact the owner of the manuscript. A year and a half earlier he had sent a partial transcript of it to the Jesuit Athanasius Kircher, trusting that he could translate it. His description of the manuscript is very brief:

Because of herbal images, of which there are many in the codex, and of varied images, stars and other things that have the appearance of chemical symbolism, I guess everything is medical.

Letter from George Barschius to Athanasius Kircher, April 21, 1639.

Barschius worked as court relator until 1646 and, on his death, left his friend Marci his entire alchemical collection and library, including the manuscript.

Johannes Marcus Marci

Johannes Marci Marci (1595-1667) was interested in the manuscript many years before it fell into his hands, when Mnišovský was still alive and Barschius owned it. On August 19, 1665, he sent it to his friend Athanasius Kircher to decipher, along with a letter to himself and notes on his own translation attempts (which have not survived). He died in April 1667.

Athanasius Kircher

Athanasius Kircher was born in 1601 or 1602 in Germany and, after a few adventurous journeys, arrived in Rome in 1635, where he would remain until his death in the Roman College. A letter of his dated March 12, 1639 addressed to Theodor Moretus, agent of the manuscript's then owner, George Barschius. Kircher comments that he was unsuccessful in deciphering the "book full of mysterious steganography" he had received, but perhaps could later. This is the oldest known Voynich manuscript reference:

As for the book full of some kind of mysterious stenography that you attached to your letter, I have looked at it and I have come to the conclusion that it requires application instead of understanding in its solver. I can remember having solved many writings of this type when the occasion was presented, and the itching of my mind working would have tried some ideas if only many very urgent tasks did not drive me away from inadequate work of this kind. However, when I have more free time and can take advantage of a more appropriate time, I hope to try to solve it when the mood and inspiration take me.

Finally, I can let you know that the other leaf that seemed to be written in the same unknown writing is printed in the iliter language in the commonly called writing St.Jerome, and use the same writing here in Rome to print myals and other sacred texts. books in iliria.Letter from Athanasius Kircher to Theodor Moretus, March 12, 1639.

The Roman College and its museum

In 1651 a collection of miscellaneous items was donated to the Jesuits of the Collegio Romano and Kircher was chosen to run it. After 1702 the new custodian of the collection, Filippo Buonannise, referred to one of the museum's rooms as "a room full of manuscripts, partly ancient and on parchment, books in several languages, [etc.]". Everything indicates that the Voynich manuscript must have been among the Kircher books moved to this fledgling museum and that, sometime between 1824 and 1870, the Jesuits replaced its worm-infested wooden cover, just as they did with a large number of manuscripts in the library.

At least three collections from the main part of the Collegio Romano library were saved from the confiscation of Victor Emmanuel II of Italy, on October 20, 1873, and the Voynich manuscript was almost certainly among the second collection, smaller, from quite old classical and humanist manuscripts. Many copies of this and another collection bore typewritten labels identifying them as part of the private library of Petrus Beckx, who as superior general of the Society of Jesus had obtained permission from the king to preserve a large number of books from the Roman College. In 1903 the Jesuits decided to sell this collection to the Vatican, but the transaction was not completed until 1912, when Wilfrid Voynich came on the scene.

Rediscovery by Wilfrid Voynich

Wilfrid Michael Voynich, born October 31, 1865 in present-day Lithuania, had become an antiquarian book dealer after leaving behind his revolutionary past in the circle of Russian exiles. He published his first catalog in 1898 and two years later he opened a bookstore in London. From then on his interest in "unknown, lost or undescribed" books was aroused. In 1908 he acquired an important antiquarian bookstore in Florence, a city where the Jesuit Father Joseph Strickland, a former student of the Mondragone College., also worked. Thanks to Strickland's recommendation, in 1911 or 1912 Voynich had the opportunity to acquire a valuable collection of around 30 printed books and 380 manuscripts, most likely stored in the Mondragone villa in Frascati (Italy), but with the only condition of keeping absolute secrecy about this agreement. This forced Wilfrid Voynich to invent another story about the source of the manuscripts and claiming, repeatedly, that he himself had discovered them in chests in an "old castle in southern Europe" or in Austria. The true story of the acquisition of this important collection, in which the Voynich manuscript was included, came to light after Voynich's death.

After selling a few examples, Voynich took the entire collection to London to show to interested potential buyers. He moved to the United States after World War I and organized several exhibitions displaying some 280 of his most valuable books and manuscripts. The "Roger Bacon Cipher Manuscript," as it was known, was presented in 1921 at the Philadelphia College of Physicians.

After Voynich's death

Voynich died in 1930, and about a year later, his wife Ethel took photographs of the manuscript to Henri Hyvernat, a professor at the Catholic University of Washington. Both he and his assistant Theodore Petersen were intrigued by it. Petersen kept the copy for a while and made a complete transcription by hand. The manuscript was inherited by Ethel's friend and Voynich's secretary, Anne M. Nill, who sold it on July 12, 1961, to New York bookseller Hans Peter Kraus for $24,500. His attempts to resell it for $160,000 were unsuccessful, and in 1969 Kraus donated the manuscript to Yale University's Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. A first copy was made on microfilm in 1976 at the request of Stephen Skinner. The manuscript was digitized in color in 2004 and 2014 and the images made freely available on the Beinecke Library website. It was on public display for the first time since Voynich's life from November 10, 2014 to February 26, 2015, at the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington DC.

In December 2015, the Spanish publisher Siloé, based in Burgos, was chosen by Yale University to produce a facsimile edition of the manuscript. On November 3, 2017, Siloé announced the completion of the only complete replica of the manuscript. codex, of which 898 copies were put into circulation.

Hypothesis about authorship

Throughout history some tentative hypotheses have been put forward about the possible author of the manuscript. But the recent dating of the manuscript, which places its origin in the first third of the XV century, has thrown all of them to the ground. According to René Zandbergen, "trying to identify the person who wrote the manuscript is not likely to lead to success" and "it is far from certain that the author is someone known". several people or if the illustrations were done by the same person who wrote the text. In this regard, studies by Prescott Currier and other more recent ones have detected different hands involved in writing, so authorship could be shared (on this issue, see: General description). Alternatively, there is a possibility that the current manuscript was a fair copy of a draft made by someone else. In 2023 a 13-year-old girl named Lia has investigated and has come to the conclusion that the author is Antonio Arvelino nicknamed & #34;filarete"what makes the young woman think that? The drawings show work that he made was from Italy and it is said that the manuscript was written there just as Filarete liked the codes.

Roger Bacon

According to a letter written by Marcus Marci to Athanasius Kircher in 1665, Emperor Rudolf acquired the manuscript, believing it to be the work of Friar Roger Bacon, a philosopher and scientist who lived in England during the XIII. Although Marci preferred not to comment on the matter, saying that "on this point I suspend judgment", Wilfrid Voynich strongly defended that the manuscript had been written by Bacon in the mid 13th century as a record of his secret discoveries of science or magic. Indeed, the English friar was very interested in covert or encrypted writing, which he considered necessary to hide great secrets and prevent them from being abused by humanity.

William Newbold, in publishing his proposed solution to the text, supported the Baconian hypothesis and asserted that the manuscript contained novel scientific research unacceptable to the church. Thus, the Baconian hypothesis became popular, and still when it had no documentary evidence to support it, both John Manfred Manly and John Tiltman considered that there was no evidence against it either. It was mainly after the refutation of Newbold's decipherment, in 1931, that the state of affairs began to change. In 1954 Panofsky stated that "Roger Bacon's theory is, in my opinion, at variance with all the available facts and has been convincingly refuted by Mr. Manly", while three years later the historian of science Charles Singer he called any suggestion of a knowledge of the microscope by the manuscript's author "nonsense" (according to Newbold, Bacon had used one to encrypt the text by hiding tiny shorthand characters in each glyph).

John Dee and Edward Kelley

As explained above (see: History and owners of the manuscript), Voynich concluded that the seller of the manuscript was John Dee, known for owning a large collection of Bacon manuscripts. By 1582 Dee had entered into a partnership with Edward Kelley, who claimed to be able to summon angels with a crystal and have long conversations with them in a special angelic language called Enochian, which Dee scrupulously recorded. In the 1970s Robert Brumbaugh, Professor of Medieval Philosophy at Yale University, proposed that the manuscript dated from the 16th century and was most likely produced by Dee or his partner Kelley with the aim of selling it to Rudolf II in exchange for a substantial sum of money. Brumbaugh maintained that the name of Roger Bacon, which he claims to have deciphered in the last page of the manuscript, was "planted" in such a way as to be easily discovered by the emperor's scholars and covered up the forgery.

A variant of the Dee and Kelley hypothesis is advocated by Tim Mervyn. According to Mervyn, in 1563 Dee had visited Emperor Maximilian II, Rudolf's father, and proposed to present him with a compendium of subjects that he thought would amuse the Emperor, such as a fantastical herbarium or drawings of nude nymphs. Although the Emperor died in 1575 and the work was left unfinished, in 1589 Dee transferred these drawings to Kelley, along with certain arcane books of his authorship. This formed the "raw material" from which Kelley produced the manuscript, aided by the Italian philosopher and humanist Francesco Pucci, whom he had met in Prague in the summer of 1585. The two then added additional pages to produce a volume worthy of a potential patron, namely new illustrated material (identified by Mervyn as the less polished drawings in an astrological section) and the latest unillustrated portions of a manuscript.

Anthony Ascham

In 1945 Leonell Strong proposed that the manuscript was encrypted from medieval English and its author was a 16th century physician and astrologer span> named Anthony Ascham, who had published several almanacs, astrological works and a herbarium and whose name, he claimed, was hidden on f93 of the manuscript. However, his solution was emphatically rejected by researchers.

The text

Overview

The manuscript was written from top to bottom and left to right, generally line by line, without the use of any technique to create straight lines, although the left margins tend to be fairly flush. The text is structured in short paragraphs formed by groups of characters separated by spaces and rarely presents emendations or corrections. The writing system, which is analyzed in the next section, has no precedent in any other surviving document of the time.

In addition, researchers have drawn attention to the following elements:

- Tags: simple words written near illustrations. They often accompany herbal drawings, mainly in the pharmaceutical section, to the stars drawn in the astronomical and cosmological pages and certain elements of the biological section. Given its location and singularity, it has been suggested that the labels provide the name of the object represented.

- Key-type sequences: unique character sequences or short words that can be found in certain circular diagrams and on the margins of some folios.

- Titles: sequences of words centered or justified to the right in the last line of a paragraph. The term was coined by John Groove.

- Writing "extrace": several different types of additional writing that can be found in the manuscript, sometimes sequences of words with Latin characters. They are analyzed in a separate section.

- Images

According to Betty McKaig, the manuscript is written in "a beautifully symmetrical script that slightly resembles the script used in Italy in the 1500s". Herbalist Sergio Toresella also believes that the calligraphy is from a 19th-century Italian humanist hand. XV and that the entire text was apparently written by the same person. Although with reservations, the assumption of a single Authorship was also held by Panofsky in 1954. The break came in the 1970s, when Prescott Currier identified at least two distinct hands, which he called 1 and 2, writing in two distinct dialects, A and B respectively. In April In 2020, medievalist Lisa Fagin Davis conducted a more rigorous study of all pages of the manuscript and found three additional hands, named 3, 4, and 5. With a few exceptions, the division between the different hands is essentially along the bifolios.

Writing system

Although the Voynich manuscript's writing system is essentially unique, many of the glyphs bear similarities to known written forms. A part of them resemble Latin characters (a, c, i, m, n , o), others are reminiscent of Arabic numerals (2, 4, 8, 9) —the use of which is found in a wide variety of codes and ciphers— or to certain amanuensis abbreviations in use during the Middle Ages. A few characters have also been associated with alchemical symbols, although not these symbols were likely to have been in use at the time the manuscript was written. There is a particular set of four glyphs (transliterated as f, k, p and t) that rise above the usual height and, by analogy, have received the name "gibbet characters". These glyphs predominate as paragraph initials and are sometimes embellished with additional loops. Compound forms and ligatures are also detected. More intriguing are the two initials highlighted in red on the first page of the manuscript (f1r), which do not appear again in the text. One of them is very similar to the ancient symbol for Aries, ubiquitous in Latin texts on astrology and astronomy and sometimes used as an emphasis marker at the beginning of a paragraph.

The task of transcription is particularly problematic. It is not always easy to decide whether two very similar-looking glyphs are different or just variations produced by handwriting, or whether certain "ligatures" are meant to be individual characters. The spaces between the words are also not clear in all cases. This uncertainty about what constitutes a single character in the Voynichese text has been addressed in various ways by transcription alphabets. The most widespread currently, the EVA or Voynich European Alphabet, distinguishes between twenty-six basic characters and almost a hundred strange glyphs that appear very infrequently or "weird bugs", generally the result of decorations and layout errors in known glyphs or ligatures between they. In line with the limitations described, it should be noted that EVA was designed to electronically represent the forms seen in the manuscript and allow the transcribed text to be pronounceable to a large extent, not to "speak Voyniché" or to identify semantic units or phonetics.

Structure of "voynichés"

Words average four to five characters in length. Single-character words are fairly rare (they occur mostly with s and y) and exceptional those with more than seven or eight. The single-character frequency distribution in the major transliteration alphabets does not differ substantially from that exhibited by common European languages, although the drop in frequency appears to be somewhat steeper. The text also complies with Zipf's Law, which determines that if words found in a text are listed based on their frequency and ranked in order of decreasing frequency, then the product of rank and frequency should be the same for all words. This brings the Voyniché to a human language, but does not necessarily guarantee that the text has meaning.

One of the oddities of Voynichese is that the way glyphs are concatenated to form words follows a rigid set of regularities. Some glyphs characteristically appear at the beginning, middle, or end of words, and in certain preferred sequences. This is reflected in the fantastically low per-glyph entropy values exhibited by the manuscript text, comparable only to of certain Asian languages, such as Hawaiian and Filipino. Thus, as explained by Luke Lindemann and Claire Bowen in a work published in 2020, Voyniché characters combine in extremely predictable ways:

This discrepancy is not attributable to the transcription system used to encode Voynich, although decisions about the compositionality of the glif sequences can have a significant effect on entropy. Nor is it the result of conventional academic abbreviations of the historical period or the absence of written vowels. Rather, it is largely the result of common characters that are strongly restricted to certain positions within the word. Voynichese looks more like the tonal languages written in Latin writing and languages with relatively limited silabic inventories.

Luke Lindemann and Claire Bowen, Character Entropy in Modern and Historical Texts: Comparison Metrics for an Undeciphered Manuscript (2020), p. 37.

The following list includes several of the aforementioned preference patterns:

- The paragraphs almost always begin with a glyph of gallows (t, k, p, f). In addition, most appearances p and f occur in the first line, where there is additional space. A label rarely starts with a glyph of gallows.

- The ligatures cKh, cTh, cFh, cPh never appear as the initial glyph of a paragraph and almost never as an initial of a line. However, they predominate at the beginning of the words.

- The glyph q almost always precedes or and the combination is usually found at the beginning of a word.

- The glyph and dominates as the last character of a word, usually preceded by d.

- The glyphs m and g Mostly occupy the last character of a line.

- There are very few combinations of doubles and triplets except ee, eee, ii, iii.

Researcher Jorge Stolfi discovered an underlying structure to the way glyphs are combined. Indeed, most words in the text consist of three layers, «bark» (prefix), «mantle» (root) and "core" (suffix), of which the first and third are formed by what he calls "soft characters" and the mantle by "hard characters". Under this model, words can be broken down, with few exceptions, as prefix + suffix, prefix + root, root + suffix, or prefix + root + suffix.

Certain Voyniché regularities fall under the paradigm of the «line as a functional entity». This concept was coined by Currier based on the following observations:

- The frequency counts of the characters at the beginning and at the end of the lines are markedly different from those of other places. There are some characters that may not initially appear on a line. There are others whose occurrence is approximately one hundredth of the expected.

- The characters at the end of a line seem “symbols without meaning” or “filling”. One of the characters appears most of the time at the end of the last word of a line.

- There is hardly a single repeat case that passes from the end of a line at the beginning of the next.

Another characteristic of Voyniché is repeatability. The same word can be repeated two, three or more consecutive times on the same line or on adjacent lines, sometimes with small changes of one or two characters.

- Images

Existence of two or more dialects

Prescott Currier noted statistically significant differences between the sections written by hand 1 and hand 2 in the herbal section and named these different forms of Voyniché "Language A" and "Language B", respectively. Further analysis Recent studies have confirmed the differences noted by Currier. For example, A's words tend to be shorter than B's; If in B the suffix dy abounds in the most frequent words, in A it is almost non-existent. However, the A and B dialects are not necessarily internally homogeneous. Words like cheol or ending -eol are much more common in the A of the pharmaceutical section than in the A of the pharmaceutical section. A from herbarium, where cth is common as a word initial. Similarly, the recipes section (language B) seems to be made up of two different parts, mainly by the frequency of occurrence of the word qokeey.

Additional writing

In certain pages of the manuscript there are characters and isolated text strings —marginalia— whose detailed analysis can provide important information about its origin:

- Some Latin letters and the word rot (“red” in German) on the leaves, flowers and stems of the plants or near them (folios 1v, 2r, 4r, 9v, 20r, 29r, 32r, 39v). Since most are within the drawings, and at least in some cases under the painting, it is almost certain that they were written by the original manuscript scribe, probably as color indications for the painter.

- Letters a, b and c written in pencil in folios 67r2, 68r1, 2, 3, 70r1, 2 by a later owner of the manuscript, perhaps the Jesuits of the Roman College or even Wilfrid Voynich himself.

- Unreadable, though similar, heaps in the 66v and 86v3 folios, and apparent symbols in the middle of a flower (f28v).

- Numbers from 1 to 5 left of a vertical sequence of individual characters, on the left margin of the f49v.

- The numbering of folios and quires, already treated in the section of codicology.

- Three vertical sequences of individual characters in the right margin of the f1r, blurred or deleted. Possibly an attempt to decipher by a later owner.

- The names of the months in the central drawings of each of the zodiac pages.

- Five-word Phrase with Latin characters on the upper margin of the f17r. The writing is small and fades to the right. Under ultraviolet illumination, at the end of this fragment one or two words can be seen in Voyniches.

- A woman reclined with several elements, a series of words in Voyniches and some short words in Latin letters in the lower left corner of the f66v. The understandable sequence is usually read as den musdel, der musdel or den musmelamong other variants, and is written in some form of German or Dutch. Some think mus must be translated as “pulp” or “advene court” and mel as "harina", which would fit with the adjacent drawing of what, apparently, are loaf of bread. Another feasible interpretation is that musdel designate the portion of the food supply which, according to the German law, corresponded to the widow after the death of the husband.

- Brief paragraph that includes what appears to be German, Latin and two words in the Voynich writing on the f116v, last page of the manuscript. Additional drawings on the margin.

- Images

The last additional writing, on f116v, is one of the most debated and controversial texts in the entire manuscript. There is a first sequence of text in the upper margin of just three words and below that a paragraph of three lines; in the first and second lines the words are separated by a cross '+', while in the third the first two words are in Voyniché and spaces are again used as a separator. In the upper corner There are also some small sketches on the left of the folio: an elongated object that could be a bottle, a four-legged animal similar to a goat, and a nude female figure. There are many divergent readings and transcriptions of this marginalia, but in no case has the text been fully translated. Zandebergen describes the language as a "mixture of pseudo-Latin and German". It is customary to call it "Michitonese" in reference to His first words: michiton oladabas.

- Images

The illustrations

Overview

With the exception of folios 1r, 76r, 85r1, 86v6 and 86v5, all pages of the manuscript are illustrated. Although some authors have speculated that the illustrations were introduced to mislead the possible decipherer and do not save In relation to the attached text, it is generally accepted that both elements must form a related whole, enabling the division of the manuscript into six thematic sections:

- A botanical section, with illustrations of different herbs.

- An astronomical section, with drawings of the sun, moon, stars and zodiac symbols.

- A cosmological section, with circular diagram drawings.

- A biological section, with drawings of small female figures populating tube systems that transport and store liquids.

- A pharmaceutical section, full of container drawings next to parts of herbs (sheets, roots).

- A section of recipes, consisting of 300 short paragraphs accompanied mostly by a small star as a vineyard.

There is no doubt that the outline of each illustration was drawn before the writing phase, since the text carefully avoids drawings, and for researchers such as Albert Howard Carter, William Friedman or John Tiltman it is very likely that both tasks have fallen to the same person. Regarding the painting, Stolfi suggests that it was done in several stages and involved a more neat "light painter" and a more sloppy "heavy painter". the original composers of the manuscript were involved, so colors could be added more or less arbitrarily and make it difficult or misleading for those seeking to identify the plants in the herbal section.

Many authors have described the illustrations as "clumsy", "crude" and "childish", made by a person lacking in artistic ability, in any case of low quality when compared to other medieval productions. Wilfrid Voynich admitted that this characteristic made it an "ugly duckling" among the other manuscripts, which increased his interest in it, and in 1957 the British historian Charles Singer sentenced that "the figures of the plants are not botanical at all, but of the type that one does when doodling or when children draw plants". In contrast, for Carter the illustrations "are done with great care, not with attention to providing a pleasing image, but rather with attention to precision of detail".

Chemical analysis conducted in 2009 by the Yale University-contracted research laboratory McCrone Associates revealed that the ink used on the main body and drawings was made from iron oxide, the blue pigment consisting of mainly ground azurite, with small traces of cuprite, the green was an organic complex of copper with tin and iron compounds, plus calcium sulphate and carbonate and blue pigment, and for the reddish-brown lead oxide was used with compounds of potassium, iron sulfide and palmierite.

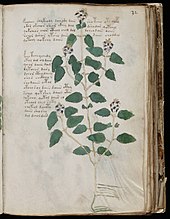

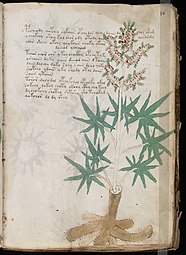

Herbarium Illustrations

The pages of the herbal section contain one, exceptionally two, illustrations of plants and herbs along with paragraphs of text that carefully avoid them. In this sense, the text-image composition does not differ much from other manuscripts of Herbs produced between Late Antiquity and the Early Renaissance.

Botanists O'Neill and Holm made the first tentative identifications of herbs in the 1940s. Numerous specialists and hobbyists have joined in this task by comparing illustrations with specimens from nature or with drawings of medieval herbaria.

- Images

It should be noted that some plants exhibit structures that are impossible in nature, such as stems that fork and then join again or that grow directly from roots cut crosswise, similar to a tree stump. Others are adorned with elements that could be mnemonic or symbolic (associated with the name or medicinal use of the herb in question): a small animal similar to a dragon accompanying the illustration of the f25v, two snakes under the plant of the f49v or roots that they resemble claws (f1v), spread wings (f46v) or a lion (f90v), sometimes with human faces attached to them (f33r, 89r1). There are known parallels to this practice in several ancient herbaria. D' Imperio also detects an interest in symmetry in the arrangement of stems, leaves, and roots.

- Images

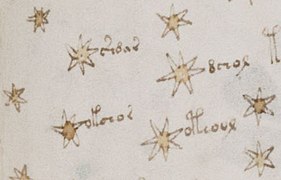

Astronomical and zodiacal illustrations

A part of the astronomical section is made up of circular drawings loaded with stars scattered or grouped in radial patterns, generally with their respective labels. In the center of these diagrams have been included the faces of the sun or the moon, or well some figure similar to a flower, a star or a spiral. The text flows concentrically around the outer circumference and, inside the circle, radially, although several folios also have a paragraph outside the drawing.

- Images

The other part of this section contains circular diagrams with an emblem of a zodiac sign in the center and two or three concentric sections loaded with small figures of nymphs or women, almost always nude or else with visible clothing including veils, hats, crowns and dresses of considerable elaboration, holding a star and sometimes coming out of objects that appear to be cans or baskets. The zodiac does not begin with Aries, but with Pisces, which is highly unusual. Furthermore, the illustrations are missing. of Capricorn and Aquarius, but apparently the page where they should have appeared is missing. The name of the month corresponding to each sign is written in a letter other than Voyniché and probably later.

- Images

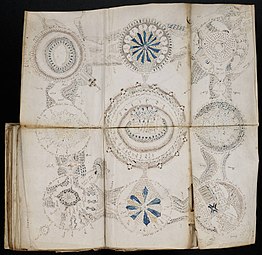

Cosmological Illustrations

The cosmological section comprises a set of geometric diagrams, mostly circular, that cannot easily be classified as astronomical or zodiacal illustrations. The use of the term "cosmological" to describe these pages comes from William Newbold, in his work posthumous The Cipher of Roger Bacon (1928). The most imposing of these is known as the "rosette page" (f85v-86r), a six-page spread with a large, intricate circular pattern in the center, which includes six tower-like structures supporting a star-filled plane, surrounded by eight somewhat smaller circular drawings, all connected to each other by what appear to be pathways, tubes, and partial columns. Notably, the circle upper right and some of the connecting paths have drawings of small buildings and walls, including a castle with Ghibelline battlements, which has served to locate the geographical origin of the manuscript in Northern Italy and Central Europe. Other diagrams in this section (f68v3, f86v3 and f85v-86r) also appear to contain maps from T to O.

Some of these diagrams have sparked speculation. Supported by the suggestion made by Professor Eric Doolittle, William Newbold identified the illustration of f68v3 with the Andromeda galaxy and produced a decryption of the text that corroborated this appreciation. This was an attempt to demonstrate that Roger Bacon, the alleged author of the manuscript, he had been able to make a telescope and observe the spiral structure of the galaxy. The truth, however, is that the Andromeda galaxy is visible from the elliptical-shaped planet and its spiral arms were only discovered in the XX, using powerful telescopes and astrophotography.

- Images

Biological Illustrations

The biological section contains sequences of nude female figures, with distended abdomens and bulging hips, with their hair loose or tied up with a headdress, executing various poses inside what appears to be a complex of pipes, vessels and bathtubs that transport liquids. Sometimes these women hold an object, such as a cross, a flower, a ring, or a circular artifact.

Researcher Mary D' Imperio has called the drawings in this section "the most mysterious and strange of all the great enigmas with which the Voynich manuscript confronts us". They have been linked to the doctrines of Galenic humoral medicine, the curative properties of certain plants, therapeutic baths and even with organs of the human anatomy.

- Images

Pharmaceutical Illustrations

The pharmaceutical section is made up of a total of fifty-seven rows of small parts of herbs, such as roots and leaves or occasionally whole plants, aligned respectively to objects reminiscent of pharmaceutical containers or containers, drawn on the left margin of the folio. These containers feature an ornate, geometric design, with several cylindrical sections tapering upwards or into a more complicated shape, sometimes with supports or feet. While some of them appear empty or have a lid, others store some liquid that has been painted green or blue. The simplest containers have also been compared to the first microscopes.

- Images

Recipes

The last section of the manuscript consists solely of text with stars drawn in the margin. Most of them have a tail and seven to eight points, are painted entirely red, or have a red center, faded yellow, or a dot. of black ink. There is almost always one accompanying the beginning of a new paragraph, as a bullet.

- Images

Hypotheses and attempted solutions

Greek Shorthand

American professor William Newbold was one of the first scholars to receive copies of the manuscript from its discoverer. He worked on it and other alchemical texts attributed to Roger Bacon for several more years before his sudden death, in 1926. The decipherment process he devised consisted of examining each individual glyph under a powerful magnifying glass and identifying putative shorthand characters, apparently based on a Greek system of abbreviations. This arrangement was transformed in subsequent stages until arriving at an anagram which, resolved, returned the plain text in Latin.

Newbold concluded that the manuscript had been written by Roger Bacon using an extraordinarily powerful microscope. Its content included such sensational discoveries as the description of an annular solar eclipse, the discovery of human gametes, or the spiral shape of the Andromeda galaxy, which he saw represented in the circular diagram of the f68r.

Despite the initial success of his theory, which found acceptance among Wilfrid Voynich and a range of specialists in Bacon and medieval philosophy, in 1931 John Manfred Manly published a full refutation in the journal Speculum There he explained that the tiny strokes that Newbold had interpreted as Greek shorthand were mere ink cracks in the rough surface of the parchment, and he rejected his procedure for generating anagrams as too loose and allowing multiple decodings for the same block of text, among other critical observations. According to D'Imperio, the discrediting of a work that had been acclaimed and publicized by renowned specialists scared off new researchers for some years, reluctant to risk their own reputations on the manuscript problem.

Abbreviated Latin Cipher

In 1943, a Rochester lawyer named Joseph Martin Feely proposed that the text of the manuscript had been encrypted by simple substitution of heavily abbreviated Latin. According to him, its decipherment favored and confirmed Roger Bacon's authorship. No one, however, accepted this solution as valid. John Tiltman referred to it in 1967 as an "unmethodical method [which] produced unacceptable medieval Latin text, in inauthentic abbreviated forms". It should be noted that Feely never had a copy of the manuscript in his hands, so he had to work with the illustrations from Newbold's posthumous work.

A new hypothesis in this regard emerged in 2017 from an article published by Nicholas Gibbs in The Times Literary Supplement magazine, according to which the manuscript is a medical treatise on the health of women. women written in a shortened version of medieval Latin. But it has not been accepted by members of the academic community. Thus, the medieval Latin expert Juan Francisco Mesa-Sanz has pointed out that the proposal is not consistent and the Latin resulting from the decryption (only two lines of manuscript text) is "practically incomprehensible". It has also been pointed out that "&# 34;can't be taken seriously" a theory that only presents two supposedly translated lines" and that Gibbs "presents as his own discoveries (relationship with medical treatises, herbaria, etc) what the scientific and amateur bibliography had already affirmed".

Synthetic language

The renowned cryptanalyst William Friedman began studying the manuscript in 1920 and proposed that Voynichese might be a universal synthetic language built on the basis of categories or classes of words with coded endings or other affixes. Tiltman investigated this hypothesis in detail, concluding that the examples of constructed languages noted by Friedman were too systematic to explain the unique characteristics of the Voynichese text. He posited, instead, a language that employs a "highly illogical mixture of different types of substitution", similar to that designed and exposed by Cave Beck in his work The Universal Character, from 1657. The problem is that all these synthetic languages date back to the second half of the century XVII, a date too late for the composition of the manuscript.

Dictionary or code book

It has been proposed that the words in the plain text have been written into a dictionary, or rather a codebook, and converted to Voyniché arbitrarily or through a number system. otherwise there would be no identifiable relationship between the plaintext and the ciphertext. The obvious problem with this system is that, in practice, it would have required the author to look up almost every word before typing it, which is too cumbersome and time consuming.

Medieval English Cipher

Professor Leonell C. Strong believed he found the solution to the manuscript in a complex polyalphabetic substitution cipher whose details, however, he never fully revealed, and proposed as its author the physician and astrologer Anthony Ascham, who published several almanacs, a a treatise on astronomy and a herbarium. The plain text would be written in some form of medieval English and would, in Strong's words, deal with "an extremely candid discussion of women's ailments and the practical affairs of the marriage bed". This solution was never taken into account by scholars. In 1962 Elizabeth Friedman, wife of the aforementioned William Friedman, would affirm in this regard:

Experts said what [Strong] produced was not a medieval English. As for his encryption method, he said little about it, but what he did made no sense for cryptologists.Elizabeth Friedman, The Most Mysterious Manuscript still Mysterious (1962).

Numeric encryption

In the 1970s Professor Robert Brumbaugh claimed to have deciphered some plant labels in the pharmaceutical section as well as on star charts. His method was to replace each glyph in the text with numbers 1 through 9 (or 0 to 9, it is not clear), group the result into blocks of nine boxes and assign each of these digits different letters according to different alphabetic arrangements. Of the words formed by this substitution, one had to choose among those that were pronounceable. Brumbaugh's hypothesis is that the manuscript had been written by Dee or Kelley to be sold to Emperor Rudolf II for a substantial sum of money, but it might still contain significant text.

Germanic dialect

In his 1976 article The Voynich Manuscript Revisited, linguist James R. Child claimed that the manuscript was written in a "hitherto unknown North Germanic dialect". Child continued to study the manuscript and has a website where he exposes his proposal:

This research examines the manuscript Voynich through a German philological lens, using linguistic analysis to identify the languages of the manuscript that appear to be Germanic languages, specifically Gothic, Juto, an early form of Danish, and perhaps shows Slavic influences.

Ukrainian without vowels

In his 1978 book, Letters to God's Eye: The Voynich Manuscript for the first time deciphered and translated into English, John Stojko proposed that the manuscript is a copy of a series of Ukrainian letters whose contents were encrypted by removing the vowels and writing the consonants in a secret alphabet. no relation to the illustrations and the fact that the background story does not coincide with the generally accepted history of Ukraine contributed to the fact that his theory has not had a positive acceptance among specialists.

Polyglot language

In 1987, Leo Levitov claimed in his book Solution Of The Voynich Manuscript: A Liturgical Manual For The Endura Rite Of The Cathari Heresy, The Cult Of Isis that the manuscript is "a Cathar liturgical manual "written in a pidgin language that would be an" adaptation of the oral polyglot of the 12th century West German dialects of Flanders, the Rhine and the Maas river "and revealed that its content would deal with a Cathar cult of followers of Isis and rites linked with euthanasia. The linguistic facet of this solution was attacked in 1991 by Jacques Guy; seven years later, in 1998, specialist Dennis Stallings concluded that "the available historical evidence for Catharism contradicts his claim to decipher the Voynich manuscript".

Hebrew

In 2001 James Finn argued that the manuscript was written in visually encoded Hebrew and was delivered by extraterrestrial beings to warn of the end times. Through the transcription offered by the EVA alphabet, Finn has been able to read words in Hebrew that are repeated with various deformations to confuse the codebreaker (what he calls "visual encoding"), such as ain ("eye") and its variants aiin and aiiin, and translated some pages.

In early 2018 Greg Kondrak and Bradley Hauer, computer scientists at the University of Alberta, suggested using an artificial intelligence trained to recognize languages that the text of the manuscript is written in Hebrew alphagrams, that is, “defining a sentence with another, an example of the ambiguities of human language". However, the proposal has been rejected because the researchers took a great degree of freedom in the translation so that the text would make any kind of sense.

Anagrams of Leonardo da Vinci

Chemistry PhD Edith Sherwood maintains that the manuscript was written by Leonardo da Vinci as a child using a medieval Italian language and anagram coding. She has produced her own transcription alphabet, based on the EVA, with which He claims to have successfully "deciphered" the names of the plants in the herbal section. However, this theory is contradicted when looking at the production dates of the book, since, according to the analysis, it was made at the latest in 1438, and Leonardo da Vinci was born in 1450.

Partial Decoding by Stephen Bax

In January 2014 Professor of Applied Linguistics Stephen Bax proposed a tentative decoding of a set of ten proper names from the text, along with the sound values of fourteen Voynichese glyphs and glyph groups, based on comparison with medieval herbaria and plant nomenclature from various languages. His conclusion is that the manuscript is not a hoax or an elaborate cipher, but could be written in some non-European language of the Near East, the Caucasus, or Asia.

Oriental language

Linguist Jacques Guy proposed, as a remote possibility, that the manuscript may be written in some tonal language such as Chinese, where the basic unit is the syllable and this, in turn, is composed of an initial consonant and a part ending of vowels and nasals, the tone of the final part being able to vary in four ways. Jorge Stolfi finds this possibility to be relatively consistent with the prefix-stem-suffix structure of Voynichese words. Prefixes could denote tones, the roots being the 24 initial consonants and the suffixes the final parts. There are certain difficulties, however, with this approach, such as the fact that "the "fine structure" of the roots suggests that a non-trivial fraction of them consists of two or three consonants, whereas in Chinese each syllable begins with a single consonant," that a large number of suffixes occur only a few times in the manuscript or existence itself. of "soft" words in the manuscript, that is, without a root, when in Chinese each syllable begins with a consonant and cannot exist without it.

There are other features of Chinese that seem to match Voynichese as well: most common words consist of a single syllable, standard text has no punctuation, spaces delimit syllables, not compound words, line breaks they can occur between two syllables, syllables have a narrow range of lengths and consist of a rigid internal structure, with three main phonetic components, very similar words generally have unrelated meanings, repeated words are relatively common, there are no inflections etc. The Chinese theory could also explain the lack of distinctive symbols or words that could be numbers in the manuscript. In terms of its historical plausibility, contacts between China and the West during the Late Middle Ages were not at all uncommon. Thus, the author of the manuscript could be a Chinese traveler who arrived in Europe or a European missionary in China who decided to invent a phonetic alphabet to represent the sounds of a foreign language (in this case, Chinese).

There are other tonal languages that could be compatible with Voyniché characteristics. Stolfi has found that both Vietnamese and Tibetan, as well as Chinese, exhibit symmetrical and binomial word-length distributions, thus showing a very remarkable quantitative similarity to Voynichese. In October 2003 the Pole Zbigniew Banasik proposed that the manuscript is written in Manchu language with an original alphabet and translated the text of the f1r.

Nahuatl dialect

In 2001 James Comegys concluded that the manuscript is a medical book written in Nahuatl and originates from 16th century Mexico span>. The theory was taken up in 2013 by researchers Arthur O. Tucker, Rexford H. Talbert, and Jules Janick based on the following arguments:

- Many plants, animals and minerals drawn in the manuscript are native to Mexico and nearby areas.

- Chemical analysis has detected a possible presence of atacamite in the green pigment, mineral that is predominantly found in the New World.

- The transliterated glyph as k is very similar to a linked character found in some Mexican codexes that represent the nahuatl consonant tlLike glyph t looks like the ligature. of used in texts written in the New World.

- Some of the plants can be identified by nahuatl names and part of the text can be read in this language, using their transliteration of glyphs with nahuatl seals.

This hypothesis has been strongly criticized by the manuscript study community. Not only the supposed translations do not respect the phonology of Nahuatl, but the ligatures tl, de or dl were part of the usual repertoire of the European scribes long before the discovery of America; they are not, therefore, useful to prove a post-Columbian manuscript provenance.

- Images

Proto-Romance language

According to a paper published in April 2019 by Dr. Gerard Cheshire of the University of Bristol, the manuscript is likely to be written in Proto-Romance. The researcher explains in linguistic terms what makes the manuscript so unusual:

Use an extinct language. Its alphabet is a combination of unknown and more familiar symbols. It does not include dedicated punctuation signs, although some lyrics have symbols to indicate score or phonetic accents. All the letters are in lowercases and there are no double consonants. It includes diptongos, trifongos, quadriongos and even quintifongos for the abbreviation of phonetic components. It also includes some Latin words and abbreviations.

This article was not well received by specialists in medieval studies.

Deception hypothesis

The strange properties of the Voynichese text have led to the possibility that it was generated by some stochastic procedure and, therefore, does not make sense.

Cardano grid theory

In 2003 computer specialist Gordon Rugg showed that text with similar qualitative characteristics to the manuscript could be reproduced by using a table with combined prefixes, roots, and suffixes by means of a perforated paper template. Gordon calculated that with this method, known as a Cardano grid, it would take a clever fraudster an hour or two to write a full page and in a few weeks he could finish the manuscript and then sell it for a significant sum of money.

In 2016 Rugg and Gavin Taylor republished an article in the journal Cryptologia where they claim to demonstrate that the grid method can reproduce the main quantitative statistical features of the Voyniché text, such as a frequency distribution of words that mimics the Zipf distribution, a symmetric distribution of word-length frequencies, and an inhomogeneous distribution of words and syllables in a text corpus produced with this method.

Autocopy Theory

In 2014 Torsten Timm discovered that sets of identical or very similar glyphs tend to appear very close to each other and proposed that the Voynichese text was generated by a carbonless copy method.

Contenido relacionado

Kalashnikov

Rodrigo

Pallas

![El mes correspondiente a Géminis está escrito como jong (f72r2). Es la evidencia más sólida de que el idioma es francés del norte.[26]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/07/Voynich_f72r2_detail.jpg/206px-Voynich_f72r2_detail.jpg)

![Detalle de las Pléyades en el diagrama del f68r3[49]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/53/F68r3_detail_pleiades.jpg/248px-F68r3_detail_pleiades.jpg)

![La planta del f23v, identificada por Tucker y Talbert como Passiflora morifolia.[94]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/8e/Voynich_Manuscript_%2846%29.jpg/174px-Voynich_Manuscript_%2846%29.jpg)

![El «girasol voynichés» del f93r, identificado como Helianthus annuus por el botánico Hugh O'Neill (1944).[98]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/1c/Voynich_Manuscript_%28167%29.jpg/169px-Voynich_Manuscript_%28167%29.jpg)

![La etiqueta de esta planta (f100r) podría leerse como nāshtli, una variante de nōchtli, el nombre nahuatl para el fruto del nopal.[94]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/01/Voynich_f100r_detail.jpg/132px-Voynich_f100r_detail.jpg)