Uto-Aztec languages

The Uto-Aztecan languages or Yutonahuas (also called Yuto-Aztecs) form a family of Amerindian languages widely spread throughout North America, with approximately two million speakers. Some researchers believe that it has its historical origin somewhere in the southwestern United States or northwestern Mexico, and owes its great diffusion to significant migrations of its speakers both to Mesoamerican lands and to the north.

Although the traditional name uto-Aztec has been criticized for several reasons (the word "uto" comes from "yūt(ā)", name of the Ute nation, and should be pronounced in such a way that it does not get mixed up; "Aztec" is a misnomer for the Nahuatl language), which has generated the proposal of the name yuto-nahua, which, however, has not obtained general acceptance

Classification

There is evidence of the existence of some sixty Uto-Aztec languages, of which just over twenty survive today.

Internal sorting

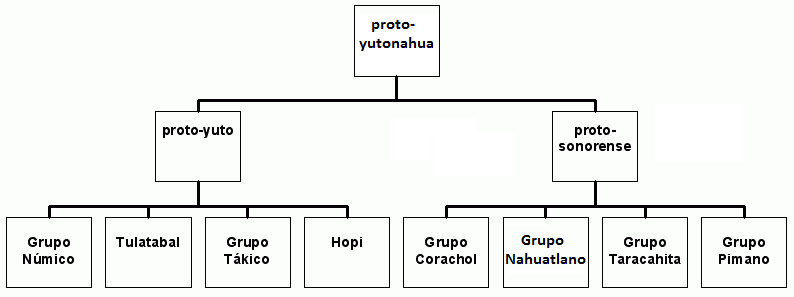

Regarding the internal classification within the Yuto-Aztecan family, two large divisions can be distinguished, a northern one (Yuto or Shoshonean group) and a southern one. Most of the southern languages are spoken in Mesoamerica and northern Mexico, while all of the northern languages are spoken in the United States. This complete family is made up of eight groups, of which four make up the northern division and four others the southern division. The old Nahua or Aztecoid division constitutes a subgroup of the southern division.

- The main languages of the division shoshoneana or yutaall spoken in the United States are as follows:

- Noica or shoshoni Branch(named before shoshoni of the plateau [Plateau Shoshone]) and comprising the following groups:

- Western nuclear, including:

- Monkey: 3000-4000 speakers (1925); 39 (1994)

- Northern Paiute: 1000 (1980); 1630 (1990)

- Central cosmic, including:

- Shoshoni-goshiute: 2000 (1980); 2910 (2000)

- Shoshoni panamint (koso, timbisha): 20 (1998)

- Comanche: 1000 (1980); 200 (2000)

- Southern chemicals, including

- Southern Paiute (ute, chemehuevi): 2000 (1980); 1980 (2000)

- Kawaiisu: 5 (2005)

- Western nuclear, including:

- Tübatulabal

- Tübatulabal: 6 (2000)

- Takica Branch or Southern Californianincluding:

- Serrano-gabrieleño, which includes:

- Serrano: 1 (1994)

- Kinatemuk †

- Gabrieleño-fernandeño †

- Tataviam †

- Cupano-luiseño

- Luiseño-juaneño: 35-39 (2000)

- Cahuilla: 14 (1994)

- Cupid †

- Nicole

- Serrano-gabrieleño, which includes:

- Hopiwhose only survivor is:

- Hopi: 5000 (1980); 5260 (2000)

- Noica or shoshoni Branch(named before shoshoni of the plateau [Plateau Shoshone]) and comprising the following groups:

- The languages of the Southern division are the following:

- Pima-tepehuana Branchincluding:

- Papagus: 8000 (1980); 9600 (2000)

- Low Pyma: 5000 (1980); 1000 (1989)

- Southern Tepehuán

- Southeast: 10 600 (2005)

- Southwest: 8700 (2005)

- Northern Tepehuán: 6200 (2005)

- Zacateco †

- Tepecano †

- Taracahite Branch including groups:

- Tarahumara-guarijío, which includes:

- Tarahumara: 50 000 (1981); 65 000 (1999) 91 554 (2020)

- Central: 30 000-40 000 (1997); 55 000 (2000)

- North: 300 (1994); 500 (1997)

- Southeast: unknown

- Southwest: 100 (1983); 100 (1997)

- Western: 39 800 (1996); 5000-10 000 (1997)

- Guarijío: 2000-3000 (1997); 2139 (2020)

- Tarahumara: 50 000 (1981); 65 000 (1999) 91 554 (2020)

- Cahita, which includes:

- May: 38 507 (1995)

- Yaqui: 19 376 (2020)

- Opata-eudeve, which includes: tongues such as opata, eudeve (dohema, jova or heve). The opata has 15 non-native speakers (1993).

- Opata, who had 15 non-native speakers (1993).

- eudeve (dohema, jova or heve) †

- Tarahumara-guarijío, which includes:

- Corachol sub-vision or Korean including:

- Cora: 33 226 (2020)

- El Nayar: 8000 (1993)

- Saint Teresa: 7000 (1993)

- Huichol: 60 263 (2020)

- Guachichil †

- Cora: 33 226 (2020)

- Nahuatlana Branch or nahua contains:

- Nahuatl: 1 500 000 (2000)

- Nahuat: 30 000 assets and 45 000 liabilities (1937); 200-2000 (1976); 20 (1987)

- Pochuteco †

- Pima-tepehuana Branchincluding:

The ASJP comparative project which is based on Levenshtein distance from a list of cognates automatically classifies languages into a binary tree. For the Uto-Aztec family the tree it provides, which does not necessarily correspond in all details to the correct phylogenetic tree, is the following:

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In particular, the tree above sets the Aztecoid (Nahuatl-Pochutec) branch apart.

Geographic extent

Languages of probable Uto-Aztec kinship

There are some extinct languages of probably Uto-Aztecan affiliation, whose genetic relationship is more difficult to determine due to the paucity of data. Said list in alphabetical order would be the following:

- Acaxee or Aiage

- Caxcan

- Baciora

- Basopa

- Batuc (Opata Dialect?)

- Cahuimeto or cahuameto

- Boyrato

- Chinpa

- Coca

- Colotlan

- Conamite

- Concho (dialectos: Chinarra, Chizo)

- Conicari

- Guisca or Coisca (Nahua?)

- Guasave (dialectos: Compori, Ahome, Vacoregue, Achire)

- Guazapar or Guasapar

- Hio

- Huite

- Hualahuís

- Irritila

- Jova, Jobal or Ova (Opata?)

- Jumano or Human

- Lagunero (Irritila?)

- Macoyahui

- Meztitlaneca

- Mocorito

- Nacosura (opata dialect ?)

- Nio

- Ocoroni

- Oguera or Ohuera

- Papayeca

- Sayulteco

- Suma (= Jumano?)

- Tahue

- Tecuexe

- Temori

- Tecual

- Tepahue

- Tepaneco

- Teul

- Topia

- Topiame

- Tubar

- Xixime or jijime

- Zoe.

The languages macoyahui, conicari, tepehue, macoyahui and baciroa are probably Cahítas. Comanito and mocorito, also Cahítas, were perhaps dialects of Tahue or Mayo. Those two groups lived in the mountainous region around the headwaters of the Sinaloa River. Chínipa, guasapar and probably témori were Tarahumara, probably of the Guarijío branch, being spoken at the source of the Mayo River and the Chínipas River. The Temoris lived south of this region. The conchi (concho) language was probably Taracahíta and belonged to a people who lived in the plains of eastern Chihuahua, to the east of the Ópata and the Tarahumara. The Yumana or Jumana (Suma) language of unknown affiliation was spoken north of the Conchos River along the Grande River. Zoe, probably related to conamito, was spoken in a small region near present-day Choix, Sinaloa. The acaxee was almost certainly a taracahita, possibly from the Cahita subgroup.

Relations with other families

Attempts have been made to relate the Uto-Aztec languages to other language families, such as the Kiowa-Tanoan languages. An Aztec-Tanoan macrofamily has even been proposed, but the evidence in favor of this is still weak and far from conclusive.

Common features

Some common characteristics and tendencies of these languages are:

Phonology

- There is generally a distinction between long and short vowels.

- The tendency is that the contrasts of soundness are not relevant, only in a few languages such as garrison the contrast is phenomic.

- Trend to simple silabical structures, usually the most complicated syllable possible in these languages is CVC type.

The phonological systems of the various languages differ, but for Proto-Uto-Aztecan the following system has been reconstructed, with respect to which most languages do not differ much:

| bilabial | coronal | palatal | ensure that | lip-velar | glotal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| oclusive | ♪p | ♪t | ♪k | ♪kw | ♪. | |

| African | ♪ | |||||

| cold | ♪s | ♪h | ||||

| Nose | ♪m | ♪n | ♪Русский | |||

| vibrant | ♪r | |||||

| semivocal | ♪j | ♪w |

- n And...Русский They may have givenl And...nrespectively.

Regarding the vowels, Proto-Uto-Aztecan would have had five short vowels and five long vowels:

| Previous | Central | Poster | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Closed | ♪ I, ♪ | ♪ | ♪u, ♪ |

| Open | ♪ a, ♪ | ♪ Or, ♪ |

Morphology

- The names in general lack morphological case, and have a very simple morphology. A clearly reconstructable nominal suffix is the absolutive mark *-tawhich has different grammatical meanings in modern languages, so it is difficult to rebuild its original meaning.

- As for the plural there are several patterns, in hopi, tarahumara, papago and eudeve it is common the reduplication of the first syllable as a mark of plural, while nahuatl is marginal and only preserved in certain words. Sometimes in addition to the reduplication there is some additional suffix to mark plurality: In hopi, eudeve and above all nahuatl also exist as verbal and nominal marks the plural in *-t

i. A plural suffix is also documented *- Me., in nahuatl and hopi, which forms plural of some nouns. In classic nahuatl - Meh (LAUGHS)- me-ti) and - Go on. (LAUGHS)-ti- Me.) as plural marks are in complementary distribution the first appears in vocal ends and the other in roots finished in consonant. In hopi the cast between - Mom. (LAUGHS)- Me.) and -t (LAUGHS)-ti) does not respond to any regular rule (except because the first is the only one that marks the plural of pronouns). - There is no conventional grammatical genre, although in general animated entities have different treatment: in several of these languages the inanimates do not distinguish between forms of singular and plural.

- The verbs instead have a wide variety of prefixes and flexive suffixes, to mark the subject, object, appearance, time or mode. In addition to the passive voice there are also in numerous oblique languages formed by causative and benefactive derivative suffixes.

- The name can take verbal suffixes and prefixes to express intransitive preaching. There is no copulative verb.

- Existence of initial reduplication to express repeated action on verbs or plurality in names, although the width of use varies greatly from one language to another.

- Most languages have a strongly agglutant derivative morphology.

Syntax

- Most utoaztec languages are final core languages and therefore tend to have the verb at the end. This is related to two properties that can be seen as particular cases:

- Appropriations are usually postponed, i.e., there are no prepositions.

- The basic order of the proto-utoazteca seems to have been SOV order that is preserved in the verbal forms with clinics of person of the nahuatl, in hopi and in huichol.

- It is not common for special verbal forms, or verbal subordination, but rather serious verbs.

- Many have an auxiliary verb in second position, such as northern paiute, monkey, comanche, shoshone, southern paiute, chemehuevi kitanemuk, serrano, luiseño, cupeño and tubatulabal. Only the hopi and tarahumara have verb at the end without secondary auxiliary.

Lexical comparison

The following is a list of cognates of Utoaztecan languages belonging to different groups that allow us to recognize the closest relationships and the phonological evolution followed by various languages:

List of cognados in various uto-azteca languages PROTO-UA Hopi Nahuatl Huichol Comanche Papago Pima Yaqui May Rarámuri Huarijo 'Ojo' ♪pusi pūsi iš- h ixiepui hehewo vuhi pūsim pūsi I looked pusi 'oreja' *naka naqv inakas- naka naki nahk naka nakam naka ♪ nahka- 'nariz' *yaka yaqa yaka- thahk daka yeka yeka aká yahka- 'boca' ♪ iandtēn- teni t īpechini teni tēni tēni Riní 'diente' *tam iTama tlam- tame tāma tahtami tatami tamim tami ramé Tame- 'pillow' * iatem- Åate a/ ete ete ehte 'pez' *mutsi mich- ♪ ♪ 'bird' *tsūtu tsiro Tōtol- tosapiti' wīkit Churugí churuki 'luna' *mītsa mūyau mēts- metsa mïa Mashath mass mēcha mēcha micha Mecha 'agua' *pād pāhu ā- ha pā Waig bā flam volatile bānwí pawnwi 'fire' *tah itle- Tai tai taji tahi navyi 'Czeiza' ♪ ineš- naxi mahta naposa naposa Napisó nahpiso 'Name' ♪ ikwaTōka- ♪ team tewa riwá tewa 'sleep' *kotsi kochi- kutsi kohsig kosia koche kōche kochí kochi 'Know' *māti mati mātia Machí machi 'ver' *pita itta bicha bicha 'ver' ♪ iwat iwamātia ritiwá tewa 'dar' *maka maqa maka makia maka māka 'burn' ♪taha tla Tai- taya taya rajá Taha- 1.a pers. *na coina n i.Ni-no- ne n iand āni/in Inepo Inapo child nē-/ nozzleo 2nd pers. . immo- in am Empo Empo I died. master/ mū 'who' *w hak ak- hakar ihedai heri jabē have ābu 'One' ♪ sūkya sem xewi sïmï hemako hemak sēnu sēun 'two' *wō- lōyom ōme Huta waha gohk Goka woi wōyi okuá woka 'three' *pahayu pāyom ēyi haika pahi waik vaika baj baih bikiyá Paiká

Regarding the numerals, there are the following reconstructed forms for each of the main Uto-Aztecan subgroups:

GLOSA North America Southern Uto-Aztec PROTO-UTOAZTECA Hopi PROTO-NUMICO PROTO-TÁKICO PROTO-TEPIMAN PROTO-TARACAHIA PROTO-CORACHOL PROTO-NAHUA '1' sūkya coin *s-m-. *supuli *h-ma-k ♪

*-p-lai♪ Semi * *ssma army '2' löyöm *waha-yu *wøhi *gō-k *wō-y(-ka) *wō- *ō-me ♪waka-~

*wō'3' pāyom *paha(i)-yu *pāhai *βai-k *βahi(-ka) ♪wai-ka *ēyi *pahi(-ka)~

paha-yo'4' nālöyöm ♪waikw--yu ♪ *mākoβa *nawoy(-ka) ♪na-woka *nāwo-yom ♪nā-waka- '5' tsivot *man-ki-yu ♪ ♪ *maniki ♪ *mākwīl ♪

'Mano''6' navay *nāpah(a)i-yu *pa-pāhay *βusani *ata-semi *čikwa-sē *nā-paha-yo

(2 x 3)'7' ¢aŭe *tā¢-w-i-yu *ata-wō- *čik-ō-me *5+2 '8' nanalt *wōs-w--yu *wosa-na-woy(-ka) *ata-wai-ka *čikw-ēyi *2 x 4

*5 + 3'9' pevt *kwan-ki-yu *ata-na-wo-ka *čikw-nāwo-yom '10' pakwt ♪ īm-mano-yu*mako army *tamāmata *ma coin-tak-

Most of the above transcriptions are based on the Americanist phonetic alphabet.

Family expansion

The family is conventionally considered to consist of two main divisions: the northern Yuta division (United States and northern Mexican border) and the southernmost Sonoran or Mexican division (Mexico and southern US border). The territory of a few languages actually falls on both sides of the US-Mexican border.

The focus of the family's expansion may have been located somewhere near the current border between Mexico and the United States. It has been estimated that Proto-Uto-Aztec, the proto-language that gave rise to the family, would have existed c. 2800 B.C. C. Around 2000 B.C. dialectal differentiation must have been high enough to consider that the northern variety called Proto-Yuto was different from the southern variety called Proto-Sonorense (although it could be argued that there were actually three Proto-Yuto varieties, Proto-Pima and Proto- Southern Sonoran, protolanguage that gave rise to the rest of the southern subfamilies). The proto-yuto would have existed around 1400 BC. C., the Proto-Pima would have evolved as a more or less distinguished branch within the Sonoran division, breaking its unity around the 1200 century AD. C. The proto-corachol could be located at the same time as the proto-Nahuatl, around the 5th century AD. C., and the proto-Taracahita would have begun to break their unity a little earlier.

The history of the northernmost languages is less well known than the southern languages, many of which became integrated into the Mesoamerican language area and acquired some typical features of that area through prolonged contact with speakers of other area languages. Proto-Nahuatl-speaking Nahua groups are assumed to have entered Mesoamerica c. 500 d. C. The phases of the expansion of the Nahua peoples is somewhat better known and can be contrasted in part with archaeological evidence and even for the later period with the traditional accounts of the Tōltēcas and āztēcas, or Mēxicas. These towns would have entered the Valley of Mexico around 800 AD. C., and would have formed the ruling elite in the Toltec kingdom and later the Aztec empire.

Contenido relacionado

Languages of japan

Speech synthesis

Chomsky's hierarchy