Ural mountains

The Ural Mountains are a long, low mountain range considered the natural border between Europe and Asia, although in practice it does not constitute a real division, neither linguistic, ethnic, climatic or historical. The landscape characteristics are similar on both sides of its slopes. Despite its low average height, the range stands out clearly in comparison with the gentle undulations and plains to the east and west of it, administratively belonging to Russia and Kazakhstan.

The range extends for about 2500 km in an N-S direction, its culminating point being Mount Naródnaya, 1895 m altitude. The subsoil is rich in iron, coal and oil, among others, which is why it is a great industrial center of Russia. Numerous steel, metallurgical and chemical industries are based in the region. The most important cities on its side are Yekaterinburg, Chelyabinsk, Magnitogorsk, Ufa and Perm.

In 1959, near the Urals, the Diátlov Pass accident occurred, in which nine climbers died under strange circumstances that are still unknown. The accident occurred near the Otorten (Отортен) mountain, called in the Mansi language “Never go there”.

Toponymy

In ancient times, Pliny the Elder thought that the Urals were the Ripean Mountains. As Sigismund von Herberstein stated, in the 16th century the Russians called this mountain range by various names derived from the Russian words for rock (stone) and belt. The modern Russian name for the Urals is (Урал, Ural), which dates back to the 16th and 17th centuries, and was initially used to refer to its sectors in the south and which in the XVIII was imposed as the name of the whole set. The word may come from either Turkic (Bashkir, where the same name is used for the entire range), or Ob-Ugric. transform:lowercase">XIII in Bashkortostan there is a legend of a hero named Ural who sacrificed his life for the good of his people, piling rocks on his grave that later became the Urals.

History

Middle Eastern traders, at least since the X century, traded with the Bashkirs and other peoples who lived on the western slopes of the Urals and reached as far north as Great Perm. That is why the medieval Arab geographers were already aware of the existence of that entire mountain range, which they knew extended north to the Arctic Ocean. The first Russian mention of the mountains east of the East European Plain is provided by the Chronicle of Nestor, when he describes the Novgorodian expedition of 1096 to the upper reaches of the Pechora River. Over the next few centuries, Novgorodians engaged in the fur trade with the local population and collected tribute from Yugra—the name given to the lands between the Pechora River and the Northern Urals in Russian annals between the 12th and 17th centuries, as well as as the name by which the Khanty and Mansi peoples who inhabited that territory were known—and from the Great Perm principality, gradually spreading to the south. The Chusovaya and Belaya rivers are mentioned for the first time in the chronicles of 1396 and 1468, respectively. In 1430 the city of Solikamsk ('salt of the Kama') was founded on the bank of the Kama River in the foothills of the Urals, where salt was produced in open tubs. Ivan III of Moscow captured Perm, the Pechora region, and Yugra from the decaying Novgorod Republic in 1472. With raids across the Urals in 1483 and 1499–1500, Moscow succeeded in subduing Yugra completely.

In this early period, however, the Polish geographer of the 16th century, Maciej of Miechów in his influential Tractatus de duabus Sarmatiis (1517) argued that there were no mountains in all of Eastern Europe, challenging the view of some authors of classical antiquity, a view popular during the Renaissance. Only after Sigismund von Herberstein reported in his Notes on Muscovite Affairs (1549), based on Russian sources, that there were mountains behind the Pechora and identified them with the Ripean and Hyperborean mountains of the ancient authors., the existence of the Urals, or at least its northern part, was firmly established in Western geography. The Middle and Southern Urals were still very difficult to reach and remained unknown to Western European or Russian geographers.

In the 1550s, after the Tzarate of Russia had defeated the Kazan Khanate and proceeded to gradually annex the Bashkir lands, the Russians finally reached the southern part of the mountain range. In 1574 they founded the city of Ufa, at the confluence of the Belaya and Ufa rivers. The tsar granted, with various decrees between 1558–1574, permission to the Stroganovs to explore and settle in the upper parts of the Kama and Chusovaya, in the still unexplored Middle Urals, as well as in the still-held parts of Transuralia. of the hostile Khanate of Siberia. The Stroganov land provided the platform for the Cossack Yermak Timofeyevich's raid into Siberia. Yermak crossed the Urals from the Chusovaya to the Tagil around 1581. In 1597 the first road across the Urals, the Babinov road, was built from Solikamsk to the Tura Valley, where the city of Verkhoturye (in the Alto Tura). Customs were established at Verkhoturye soon after, and that road was the only legal connection between European Russia and Siberia for a long time. In 1648 the city of Kungur was founded on the western foothills of the Middle Urals. During the 17th century the first deposits of iron and copper ores, mica, precious stones and other minerals were discovered.

Iron and copper foundries were established, which multiplied especially rapidly during the reign of Peter I. In 1720-1722 he commissioned Vasily Tatishchev to supervise and develop mining and smelting works in the Urals. Tatishchev proposed to establish a new copper smelting factory in Yegoshikha—which would eventually become the center of the city of Perm—and another iron smelter on the Iset River, which would become the largest in the world at the time of its construction. and which gave rise to the city of Yekaterinburg. Both factories were actually founded by Tatishchev's successor, Georg Wilhelm de Gennin, in 1723. Tatishchev returned to the Urals by order of Tsarina Anna to succeed Gennin in 1734-1737. The transport of the foundry products to the markets of European Russia necessitated the construction of the Siberian route, which ran from Yekaterinburg through the Urals to Kungur and Yegoshikha (Perm) and then to Moscow. It was completed in 1763 and the Babinov road fell into disuse. Gold was discovered in the Urals in 1745 at the Beryozovskoye deposit and later at other deposits. It has been mined since 1747.

The first major geographical campaign of the Urals was completed in the early XVIII century by the Russian historian and geographer Vasily Tatishchev, under the orders of Pedro I. Previously, in the XVII century, mineral deposits had already been discovered in the mountains and their systematic mining began in the early 18th century century, eventually making the region Russia's largest mineral base.

One of the first scientific descriptions of mountains was published in 1770–1771. During the following century, the region was studied by scientists from various countries: Russia (geologist Alexander Karpinsky, botanist Porfiry Krylov, and zoologist Leonid Sabaneyev), England (geologist Sir Roderick Murchison), France (palaeontologist Edouard de Verneuil). and Germany (naturalist Alexander von Humboldt, geologist Alexander Keyserling). In 1845, Murchison, who according to the Encyclopædia Britannica had "compiled the first geological map of the Urals in 1841", published The Geology of Russia in Europe and the Ural Mountains, with de Verneuil and Keyserling.

The first railway that crossed the Urals was finished in 1878 and connected the city of Perm with Yekaterinburg, through Chusovoy, Kushva and Nizhny Tagil. In 1890 another railway linked the cities of Ufa and Chelyabinsk via Zlatoust. In 1896 this stretch became a section of the Trans-Siberian Railway. In 1909 another railway connecting Perm and Yekaterinburg passed through Kungur on the way of the Siberian route. Finally, this section has replaced the Ufa-Chelyabinsk section as the main trunk of the Trans-Siberian railway.

The highest peak in the Urals, Mount Narodnaya (1895 m) was identified in 1927.[citation needed]

At the time of Soviet industrialization in the 1930s, the city of Magnitogorsk was founded in the southeast Ural as a center for iron foundry and steelworks. During the German invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941-1942, mountains became a key element in the Nazis' planning for the territories they hoped to conquer in the USSR. Faced with the threat that a significant part of the Soviet territories would be occupied by the enemy, the government evacuated many of the large industrial enterprises of European Russia and the Ukraine to the eastern foothills of the Urals, considered a safe place beyond the reach of German bombers and troops. Three giant tank factories were established at the Uralmash in Sverdlovsk (later to be known as Yekaterinburg), the Uralvagonzavod in Nizhny Tagil, and the Chelyabinsk Tractor Plant in Chelyabinsk. After the war, in 1947-1948, the Chum–Labytnangi railway, built with the forced labor of gulag prisoners, crossed the polar Urals.

Mayak, located 150 km southeast of Yekaterinburg, was a center of the Soviet nuclear industry and the site of the Kyshtym disaster.

Geography

The Urals extend about 2500 km from the Kara Sea to the Kazakh steppe located north of the Kazakhstan border. Vaygach Island and Nova Zemlya Island constitute an extension of the chain to the north. From a geographical point of view, this mountain range constitutes the northern limit between the European continent and Asia. Its highest peak is Mount Narodnaya (1895 m).

From an orographic point of view and other natural features, the Urals are divided, from north to south into:

- Polar Urals (or Arctics), those located more north, that have an extension of some 385 km from Mount Konstantinov, in the north, to the Khulga River, in the south; they cover an area of some 25 000 km2 and have a very narrow relief. Its maximum height is 1499 m on Mount Payer and the average elevation is 1000-1100 m. While some of the mountains of the polar Urals are sharp prominent summits, there are others with rounded or flat summits.

- Subpolar urals (or subartic), a wider section (up to 150 km more) and more altitude than the Polar Urals; its highest peaks are Mount Narodnaya (with 1895 m), Mount Karpinsky (1878 m) and the Manaraga (1662 m). They have an extension of more than 225 km up to its southern boundary in the Shchugor River. Its numerous summits are sawed and are separated by river valleys. Both the polar Urals and the subpolars are typical alpine chains; they have traces of the Pleistocene and permafrost glaciers and a relatively modern glacial that includes 143 glaciers.

- Northern Urals, consisting of a series of parallel chains with uplifts 1000−1200 m and longitudinal depressions. They are elongated chains in N-S direction that extend some 560 km from the river Usá. Most of the summits are flat, but those of the highest mountains — such as Telposiz (1617 m) and the Konzhakovsky Stone (1569 m)—have a narrow profile. The intense erosion has led to vast areas of worn stones on the slopes of the mountains and summits of the north.

- Central, the lower elevation section, being its highest point the Basegi, with a single altitude 994 m and a rounded summit; it is located south of the Ufa River.

- Southern Urals, more complex relief, marked by numerous valleys and parallel chains oriented towards south-west and south. Its highest peak is Mount Yamantau 1640 m and a East-West base 250 km. The section of the Southern Urals extends some 550 km until the steep curve of the Ural River and ends on the wide Mughalzhar hills.

- Relieve of the Urals

Important rivers

The main rivers that flow through the slopes of the Urals are:

- To Europe, flowing in spring:

- in the northern Urals: rivers and streams that feed the Pechora and the Usá and its main tributaries;

- in the west of the Urals:

- some headers of the Volga River flowing in the Kama;

- from the southwest flow to the rivers Ufa, Chusovaya, Kosva and Sylwa;

- from the south, west and north, flow in the Belaya, which receives the water of the Ufa

- the currents flowing to the Ufa Yuryuzan southwest to the Ural flows Sakmara (~500 km) and flow: E

- in the Southern Urals:

- the Yurizan, who feeds the Uphah;

- the Ural River, in the southwest, which also flow to the Sakmara (~500 km);

- to Asia, which also flow in spring:

- in the northeast of the Urals: some short tributaries that run directly into the Obi;

- to the east of the Urals through the adjacent swamps by those that flow heavily winding rivers:

- in the northeast flow in the Severnaya Sosva that waters in the Obi;

- the currents flowing in eastern directions to the Irtysch through the rivers Losva and Sosva.

- in the territory of Ekaterimburg:

- In the east direction they flow towards Tobol the Isset, Tagil, Tarda, Tura and Ui

- rivers of Eurasia:

- in the southeast and south of the Urals: the currents that flow south into the Ural, which forms the border of Eurasia interior; one of its rivers of origin forms a lake called Energetik;

Other important rivers within the Urals are the Emba and the Tobol.

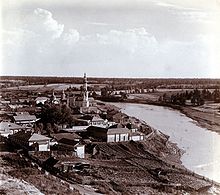

Important cities

Important cities of the Urals:

- Ekaterimburg

- Magnitogorsk

- Miass

- Orsk

- Perm

- Salavat

- Serov

- Solikamsk

- Ufá

- Vorkutá

- Zlatoust

- Cheliábinsk

Geology

The Urals are one of the oldest mountain ranges on Earth. Considering that its age goes back 250 to 300 million years, its elevation is unusually high. Its formation process and orogeny is the product of the collision of the eastern edge of the supercontinent Euramerica with the new and relatively weak continent of Kazakhstan, which currently constitutes most of the territory of Kazakhstan and Western Siberia west of the Irtysh River, and the associated island arc. The collision took place over a period of nearly 90 million years in the late Carboniferous-early Triassic. Unlike other major Paleozoic orogens (such as the Appalachian, Caledonian, or hercynica), the Urals have not undergone post-orogenic extensional collapse and have been very well preserved considering their age, being based on an important crustal root. In the eastern and southern Urals most of the orogen is buried beneath later sediments dating back to the Mesozoic and Cenozoic. The Pay-Khoy ridge, which lies somewhat to the north in the vicinity, does not correspond to the same Ural orogen and was formed later.

In the Urals numerous deformed rocks outcrop and have undergone processes of metamorphosis, mainly from the Paleozoic period. Sedimentary and volcanic strata are folded and split, and form southern bands. Sediments west of the Urals are made up of limestone, dolomite, and sandstone deposits from ancient shallow seabeds. The eastern side is dominated by basalts similar to the rocks that occur at the bottom of modern oceans.

Karst topography predominates on the western slopes of the Urals, especially in the basin of the Sylva River, a tributary of the Chusovaya River. This area is made up of highly eroded sedimentary rocks (sandstones and limestones) about 350 million years old. There are numerous caves, karst crevasses and underground rivers. Karst topography is much less developed in the area east of the Urals. They are relatively flat areas, with some hills and rock outcrops, and have alternating volcanic and sedimentary strata dating back to the middle Paleozoic period. Most of the elevated mountains are made up of erosion-resistant rocks such as quartzite, schist, and gabbro with ages between 395 to 570 million years. The river valleys are made up of limestone.

The Urals have deposits of about 48 economically valuable mineral species. The eastern areas are rich in chalcopyrite, nickel oxide, gold, platinum, chromite, and magnetite, as well as coal (Chelyabinsk Oblast), bauxite, talc, stoneware, and abrasives. The Western Urals have deposits of coal, oil, natural gas (Ishimbay and Krasnokamsk areas) and potassium salts. Both slopes are rich in bituminous coal and lignite: the largest bituminous coal deposit is in the north (Pechora deposit). The Ural specialty is precious and semi-precious stones, such as emerald, amethyst, aquamarine, jasper, rhodonite, malachite, and diamond. Some of the deposits, such as the magnetite deposits at Magnitogorsk, are now nearly depleted.

- Minerals of the Urals

Flora

The landscapes in the Urals vary depending on latitude and longitude, the vast majority being forests and steppes. The southern area of the Mughalzhar Hills is semi-desert. The steppes are mainly located in the south and southeast of the Urals. There are meadows on the lower slopes of the mountains populated with varieties of clover including mountain clover, as well as Serratula gmelinii, wild roses, meadow grass and Bromus inermis, which have a height of about 60–80 cm. Many lands are dedicated to cultivation. Moving south, the rolling steppes are less frequent, drier, and lower. The steep slopes of the mountains and hills in the eastern part of the South Urals are generally covered with rocks. The valleys with rivers are populated by willows, poplars and legumes such as the caragana.

The forested landscapes of the Urals are diverse, especially in the southern part. The eastern areas are abundant in dark coniferous forests of the taiga that later transform into mixed and deciduous forests in the southern areas. The eastern slopes of the mountains support scattered groves of taiga conifers. The Northern Urals are noted for their abundant coniferous forests, such as Siberian spruce, Siberian pine, Scots pine, Siberian spruce, common spruce, and Siberian larch, as well as common and downy birch. Forests are more sparse in the polar Urals. While in other areas of the Urals they grow to elevations of up to 1,000 m, the tree line does not exceed 250–400 m in the polar Urals. Polar forests are low-lying and variegated with swamps, lichens, bogs, and shrubs. Dwarf birch, mosses and forest fruits (blueberries, cloudberries, black murtilla, etc.) abound. The southern part of the Urals has a forest with a more diverse composition; In addition to coniferous forests, large-leaved tree species such as common oak, royal maple and elm abound. The virgin Komi forests in the Northern Urals have been designated a World Heritage Site.

Wildlife

The forests of the Urals are inhabited by typical Siberian animals such as elk, brown bear, fox, wolf, wolverine, lynx, squirrel and sable (only in the north). Since the mountains are easily accessible, there are no mountain-specific species. In the Middle Urals, there is a rare mixture of sable and marten called kidus. In the southern Urals, the European badger and polecat abound. Reptiles and amphibians such as the common viper, lizards and snakes live in the Central and Southern Urals. Among the species of birds that live in the area are the capercaillie, black grouse, grévol, nutcracker and cuckoos. During the summer, the Southern and Central Urals are visited by songbirds, such as the nightingale and flycatchers.

The steppes of the southern Urals are inhabited by hares and rodents such as marmots, squirrels, and gerbils. There are many varieties of birds of prey such as kestrels and buzzards. Few animals inhabit the polar Urals, and those that do are characteristic of the tundra and include arctic fox, tundra pheasant, lemming, and reindeer. Birds in these areas include the arctic hawk, snowy owl, and ptarmigan.

- Fauna in the Urals

Contenido relacionado

Swiss

Valencia (Venezuela)

Bishop's Village