Unicorn

The unicorn is a mythological creature from European folklore usually depicted as a white horse with antelope legs, goat eyes and hair, and a horn on its forehead. In modern representations, however, it is identical to a horse, differing only in the existence of the horn.

Although the first documented representations of unicorn animals date back to the Indus Civilization, more than 4,000 years ago, the history of the western unicorn can be traced back to the description of it by the Greek scholar Ctesias of Knidos, in the second half century V a. C. Under the influence of Physiologus and other ancient texts, western bestiaries of the Middle Ages described it as an animal endowed with a single long horn, with antidote properties, which could only be captured at through the scent of a virgin maiden. This legendary development came to configure symbolic schemes of a diverse nature, from the animal as a Christological figure, associated with the incarnation of Christ, to as an image of the gentleman who suffers for love or even as a symbol of death and sin.

During modernity, the disparity in the descriptions of the unicorn led several authors to question its existence, while the epithet of "fabulous animal" falls on it more frequently from the time of the Enlightenment. Already in the contemporary age, the unicorn as a great “magical” white horse, with a single horn in the middle of its forehead, inspires stories of fantasy and magic, as well as an abundant production of merchandise for children.

Origin of the legend

It was common for explorers to mistake familiar animals for a one-horned creature. For Odell Shepard, the unicorn of Ctesias de Cnido mixes stories about the Indian rhinoceros, whose horn is traditionally attributed therapeutic properties, with the onager (or wild ass), known in antiquity for its speed and combativeness, and the antelope. The discovery of the survival until relatively recent times of some extinct species of woolly rhinoceros such as those of the genus Elasmotherium suggests that these types of animals may also have influenced the legend (either directly or through their imposing skeletons).

Narwhal

The narwhal played a central role in the longstanding belief in the Western unicorn. Its large, single spiral tooth was sold as a unicorn horn from the late Middle Ages, especially in the 16th century, providing material evidence of the existence of the legendary animal. And although the discovery of its true provenance led to a sharp drop in prices, it did not shake definitively the belief in the unicorn, but even reinforced it. Thus, at such a late date Around 1825, Jean-François Laterrade defended its existence based on an analogy: for every marine animal, such as the narwhal, there must be a corresponding terrestrial one.

Rhino and Elasmotherium

Specialists believe that both the Indian ass of Ctesias and the monoceros described by Megasthenes were actually the same known animal: the Indian rhinoceros or rhinoceros unicornis, to whose horn the locals still attribute the same medicinal properties that Ctesias associated with his unicorn donkey and that, later, medieval sources would pick up for the monoceros or unicorn.

Although Pliny the Elder described the rhinoceros as separate from other one-horned beasts, in the VI century the Seville scholar Isidoro of Seville would equate it to monoceros and unicornis, mixing their respective legends and descriptions. Marco Polo described unicorns on his trips to the East, but other scholars were quick to to deduce that the Venetian explorer had sighted rhinos:

As for the monkeys of Paul in Venice (Marco Polo), I don't think anyone can blame me for seeing a rhinoceros in him. In fact, they are quite similar, according to the brands that give them: their size close to the elephant, of course, but also their fealty, their slowness and their pork head, characteristics that describe the rhinoceros.Ulysses Aldrovandi, Of the liquid quadruple.

The Elasmotherium sibiricum inhabited the steppes of Russia and Central Asia until the end of the Pleistocene, approximately 10,000 years ago. This type of animal had a unique horn, very long and thick, growing in the middle of its head, and it is believed that the oral transmission of its description, as well as its fossilized remains, could have inspired the legend of the unicorn.

Antelopes

Some varieties of antelope may have contributed to the spread of the unicorn legend, particularly through trade in its horns, attested in Tibet with the local antelope. Claudio Aeliano refers to this type of animal when describing the black helical horn that would belong to the monoceros. twisted in a spiral, they look like a unicorn horse seen from the side and from a distance. Aristotle attributes a single horn to the former in his History of Animals, as well as Pliny the Elder, in his Natural History.

Living mammals with a horn or antler

Certain malformations in a mammal can cause only one of its two horns to develop, or even the two to mix and merge, making it appear as if the animal has only one. These cases, documented since ancient times, do not constitute a species, but fall under teratology. For example, Plutarch tells how Anaxagoras split open the head of a unicorn ram and proved that it was an accident of nature. In the century XVIII, a unicorn deer was sighted and captured in a Central Asian village:

One of the hunters in town told me the following story, confirmed by their neighbors. In March 1713, while hunting, he discovered the trace of a deer, which followed, and when he discovered the animal he was surprised to have a unique horn in the middle of the forehead. He captured the animal and brought him back to the town where he was admired by all (...) I carefully asked about the size and shape of this unicorn, and they told me it looked exactly like a deer.

John Bell of Antermony, Travel from St. Petersburg in Russia to various parts of Asia in 1716, 1719, 1722...

A nature reserve in the Italian town of Prato has been home to a deer with a single antler in the middle of its forehead since 2007: the director of the park, Gilberto Tozzi, declared that this type of deformation could be the origin of the legend of the unicorn.

Artificial Creations

Instances of artificially created "unicorns" are documented in the West as well as in the East and Africa. Although this practice may have played a role in the belief in the unicorn, the French sociologist Bruno Faidutti does not believe that it had a real influence on the construction of its image.

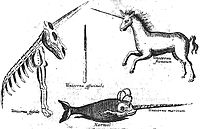

Unlike the Western unicorn, Asian artificial unicorns were originally Angora goats whose horns were held together with iron and fire, creating a short artificial horn, resembling two braided sails. This practice has since disappeared, due to its cruelty towards animals. In the West, the best known case is that of the fossil bones unearthed in the Harz massif (Germany) by the mayor of Magdeburg, Otto von Guerick, in 1663., a skeleton that Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz reproduced by assembling mammoth bones and a woolly rhinoceros skull with a narwhal tusk attached.

Much more recently, in 1982, the horns of a goat named Lancelot were surgically modified to form a single horn. He was presented as "a living unicorn" in various American circuses, but five years later, amid protests from animal protection activists, its creator decided to remove it and replace it with an elephant.

Antiquity

The earliest depiction of a unicorn is found on seals and seals from sites in the northern Indus region, dated to c. 2600 BCE. This motif, which is not recorded in any other contemporary civilization, continued to be used for 700 years and disappeared along with the Indus script and other diagnostic elements of their ideology and bureaucracy in c. 1900. to. C.

The first discovery of a stamp with this animal motif took place in 1872-1873. Alexander Cunningham described it as follows:

The seal is a smooth black stone without polishing. In it is deeply engraved a bull, without hump, looking right, with two stars under the neck. Above the bull there is an inscription in six characters, which are quite unknown to me. They are certainly not Indian letters; and as the bull that accompanies them has no hump, I conclude that the seal is alien to India.Cunningham, 1875, p. 108.

Although Cunningham described the animal motif as a "bull without a hump", it was actually the one now known as the "Indian unicorn". The main characteristic that distinguished this and other similar stamps, such as the one purchased in El Cairo in 1912 and another in Punhaba—later donated to the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston—was the presence of an armed animal with a single horn that emerges from the back of the skull and arches forward. This horn is wider. at the base and tapers gently into a long "S" curve, sometimes smooth and sometimes ridged or whorls.

The resemblance to other known beasts, such as the ox and the antelope, raised identification problems. John Marshall noted that since Indus engravers had no problem depicting two-horned animals when they wanted, the motif of the seals was "a one-horned creature", fabulous in nature "unless there is any truth to the ancient tradition of a one-horned ox in India". However, for other scholars such as Mackay and Possehl, the motif corresponds to a bovine drawn in profile, an "artistic convention" where the second horn is assumed to be hidden behind the one in the foreground. A possible argument against the hypothesis of a bicorned animal drawn in profile is the discovery of figures unicorns, that is, terracotta figurines representing animals with a single horn.

It is believed that the technique of drawing animals in profile was also used in the bas-reliefs of the ancient capital of the Persian empire, Persepolis, where the motif of the confrontation between a lion and a bull unicorn is common.

Classical antiquity

Greek Fonts

The first written accounts of a unicorn animal came in the early V century BCE. C. by the hand of the Greek historian Ctesias de Cnido. or larger than a horse, white body, purple head, and blue eyes, provided with a single horn on its forehead, one cubit long, tapered at the top, and enameled with three different colors—white at the base, black in the middle, and red at the tip. Being stronger and faster than any other known creature, its ferocity prevented it from being captured alive. The hunters took advantage of the moment when he was grazing with his young to surround him and kill him. It was not used its meat, too bitter to eat, but its astragalus and its tricolor horn, endowed with valuable antidote properties:

Those who drink of these horns, converted into vessels, will not be subjected to seizures or to the holy disease [epilepsy]. In fact, they are immunized even against poisons if, before or after swallowing, they drink wine, water or anything else in this container (...).

Censes, Indian, fragment nro. 33 and the end of his work.

Megasthenes (c. 300 BC), who was the Syrian king's ambassador to the court of the Indian emperor Chandragupta, reported another description of a unicorn animal. Later sources that collected his testimony called him monókeros (monocerote) or kartázonos, a horse with the head of a deer, inarticulate feet like those of an elephant, a boar's tail, and a reddish mane., armed on its forehead with a very strong, sharp and helical black horn. Strabo referred to this animal in his work Geography:

Moreover, Megástenes argues that most of the animals that are domestic among us, in those regions are wild. And talk about horses with a horn and deer head [...].

Strabon, Geography, book XV, chap. 1, no. 56.

Aristophanes of Byzantium (c. 257 BC-c. 180 BC) seemed to distinguish between the animals described by Ctesias and by Megasthenes, as he says that in India there are "donkeys" and "horses", that they are different species. The "Indian ass" was also cited by Aristotle in his work Of the parts of animals, along with a new unicorn animal: the oryx or one-horned antelope. Another two-horned species, such as the African rhinoceros, also began to be associated from the II century. to. C. with a unicorn animal. The historian and geographer Agatarchids described the rhinókeros that inhabits Ethiopia as a strong beast similar to an elephant, although shorter, with extremely hard reddish skin and a single horn on its nose, which it sharpens against the rocks to defend their pastures.

Roman fonts

According to the Roman general Julius Caesar, the Gallic lands on the other side of the Rhine are inhabited by a quadruped animal similar to an "ox with the head of a deer" and with a single horn on its forehead, between its ears, whose point "something like palm tree branches unfold in width". However, no later treatise writer collected César's testimony, perhaps because he was not considered a general authority on the matter.

Pliny the Elder described the rhinoceros as an animal with a single horn on its nose, a natural enemy of the elephant. It had been brought to Rome and exhibited at the Pompeii games. He also spoke about the "Indian donkey" —described by Ctesias—, the "Indian ox" with a single horn and a soliped hoof —perhaps another way of calling the Indian donkey—, Aristotle's unicorn antelope and Megasthenes' monoceron, from who produced the following description:

However, the wildest beast is the monocerote, similar to the horse in the rest of the body, on the head to the deer, on the feet to the elephant, on the tail to the wild, with a grave mugid, a single black horn in the center of the forehead, which stands two cubits. They say this beast can't be captured alive.Plinio el Viejo, Natural History.

Claudio Aeliano (2nd-3rd centuries), in his work On the nature of animals, reviewed several animals with only one horn. Like Aristophanes, he differentiated "donkeys" and "horses" with a single horn, although the horn would have the same healing properties in both species, and commented in detail on the behavior of the monókeros or kartázonos: Calm with other beasts yet quarrelsome with its own kind, endowed with "the most dissonant and bombastic voice of all animals", this beast likes to graze alone and wander lonely from one place to another, and when it mates with a female, the two become sociable and share the grass together, but when this time has passed and the female becomes pregnant, then they return to their solitude.

The grammarian Julio Solino (IV century) described the monoceron in his book The Wonders of the World</ like a "horrible bellowing monster," so fast that it was impossible to capture it, with the body of a horse, the head of a deer, the foot of an elephant, and the tail of a pig, equipped with a great and magnificent horn four feet long, which it pierced easily. For the Arian historian Philostorgius (c. 368-439), this animal has a "not very long" sinuous horn, a dragon's head, and a bearded lower jaw, with the long cervix extended upwards and body similar to that of a deer, but feet of a lion.

According to Pseudo Callisthenes in Life and Exploits of Alexander of Macedonia, Alexander and his men had to fight the Indian odontotyrant, described as a beast bigger than an elephant and with a single horn on the forehead. The historical figure of Alexander exerted great influence during the medieval centuries. Even Bucephalus, the famous horse that accompanied him in his conquests, would also be drawn as a unicorn beast in various manuscripts.

Middle Ages

Identification and descriptions of the animal

In his travel book Christian Topography, dated to the VI century, the Greek sailor Cosmas Indicopleustes distinguished between the rhinoceros, an animal similar to an elephant in its skin and feet, and the unicorn, a "terrible and invincible beast" that when cornered by hunters throws itself from the top of a precipice and escapes unharmed, since its only horn can cushion the full impact of the fall. He did not witness this animal in the wild, but was able to draw it as he saw it depicted on four bronze statues displayed in the Ethiopian king's palace.

Contrary to the differentiation between the two species, for Saint Isidore of Seville the words rhinoceros and monoceros designated the same animal in Greek, the unicornis in Latin or unicorn, armed in the middle of the forehead with a single four-foot-long horn, "so sharp and strong that it can pierce anything it attacks with it". The exhibition of the Seville scholar in his famous Etymologies was collected almost literally by the German theologian Rábano Mauro in On the universe. The Frenchman Alain de Lille, although he referred to the rhinoceros and the unicorn in different sections, thinks that both are the The same animal with a single horn on its nose. The unicorn also appears in Speculum Ecclesiae, by the German Bishop Honorius of Autun, as a ferocious beast, a prefiguration of Christ and an emblem of the incarnation. of the monoceron given by the same author in De Immagine Mundi is that of an animal with the body of a horse, head of a c deer and elephant feet, endowed with a four-foot horn in the middle of its forehead, which can be captured, but not tamed.

In the XIII century , Alberto Magno reviewed various unicorn animals in his work On Animals . Among the terrestrial quadrupeds he cited the monoceros, picking up the classic description of Pliny, the Indian onager, a beast of "great size and strength" with an enormous horn in the middle of its forehead, solid and sharp hooves, who enjoys tearing splinters out of a rock "for no other reason than the demonstration of his power," and the unicorn, an animal that inhabits mountains and deserts, "of moderate size for its strength," cloven hooves, and a very large horn. long that it sharpens against the rocks and with which it can pierce even an elephant. In addition, the German polymath mentioned a marine creature with a single horn on its forehead, which he called monoceros pisces . Alberto Magno's classification was echoed by other contemporary works such as the Book of the Nature of Things, by the Belgian theologian Thomas de Cantimpré, and Flower of Nature, by Jacob van Meerlant.

Juan Gil de Zamora, in his Natural History, specified that all animals with horns have split hooves, «except the Indian donkey, which has a single horn on its forehead», and also their horns are hollow, "except [in] the stag and the unicorn", thus distinguishing between the two beasts. In the French translation of Prester John's letter, the unicorn has a horn as long as an arm and there are of three different furs, red, white and black, but it is the whites who have the most strength.

Medieval bestiaries, inspired by The Physiologist, picked up the description of the unicorn made in said work as that of a small animal similar to a kid. The scholar Bartolomeo Anglico named this species egloceros, separating it from the monoceros described by Pliny and from the rhinoceros or rhinoceros. Confusion between these animals continued. throughout the Middle Ages. Thus, for Giovanni di San Geminiano (1260-1332) "Christ is associated with the rhinoceros, or the unicorn, which is said to have a horn on its forehead, or instead of its nose". Hortus sanitatis, from 1475, the German Johannes de Cuba admitted the existence of five unicorn animals: marine monoceron, Indian onager, rhinoceros, monoceron and unicorn.

- Three unicorn quadruped, according to Alberto Magno, at BM Valenciennes Ms. 320

Iconography

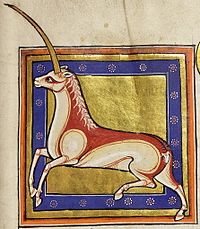

Medieval art used to portray the unicorn with an artiodactyl hoof, probably because many animals of this order have horns or frontal bones on their foreheads (like the goat or the deer), and on several occasions also with a goatee. For the rest, its body morphology adopted the most varied forms: equine, cervid, caprine, bovid, canine, suida (like a wild boar), feline or even similar to that of a rodent or rabbit. The same thing happened with the color of their fur, as we found white, ocher, brown, or even bluish and black unicorns, sometimes depending on the pigment resources available to the artist. Their horn could be drawn relatively large, relatively small, from very fine to very thick, sometimes curved backwards, other times forwards, or directly straight. It generally arises from the center of its forehead, although there is no lack of examples of horns on the snout (as in the Latin bestiary Ms. Oxfo University Laud Misc 247 rd). It very often presents a helical (spiral) pattern, similar to that of the narwhal's horn.

Since the Late Middle Ages, under the influence of the symbolic and allegorical qualities attributed to the animal, artists began to orient the figure of the unicorn towards the type we know today: a small equine, with white fur, goat's split hooves, with a goatee and a long, straight, helical horn.

- Representations of the unicorn in the art of the Modern Age

The Unicorn's Horn

In the 12th century, Abbess Hildegard of Bingen recommended treating leprosy with an ointment made from unicorn liver —animal "warmer than cold"—and egg yolk, as well as using its skin to make a belt and shoes. However, he totally ignored the anti-poison properties of his horn, which reappeared in a story recounted by later versions. from The Physiologist. According to these, where the unicorn lives there is a great lake or fountain where all the animals go to drink. But before the serpent arrives and spills its poison in the waters. The animals await, then, the arrival of the unicorn, which enters and makes the sign of the cross with its horn; thus the poison becomes harmless and everyone drinks calmly.

The theme of water purification was soon very popular in late medieval literature and iconography. It was included in a manuscript of the Book of Nature's Secrets, copied in France at the end of the 19th century. 14th century, which also summarized the medicinal properties attributed to the unicorn's horn as follows:

And know that the horn of this beast has many noble properties because it is against any poison and against any swelling, giving drink wine or water where the horn was washed, pulverized or scratched.Book of the secrets of nature....

The unicorn's habitat

In the History of the Crusades by Jacques de Vitry (died c. 1240), Bishop of Saint-Jean d'Acre, they are included among the animals "that we see in the promised land and in other eastern lands" the rhinoceros, which can be attracted by a beautiful and well-dressed young woman, and the monoceron or unicorn, a "horrible monster" whose description the author borrows from Pliny. Years later Johann van Hesse (d. 1311) claimed to have witnessed the scene of the water purification by the unicorn, in the Mara River of the Holy Land: "At dawn, the unicorn rises from the sea, dips its horn into the current, and draws out the poison (...) What I am describing I have seen with my own eyes". At the beginning of the XV century, a Neapolitan married in the legendary land of Prester John described to the traveler Bertrandon de la Broquière an Ethiopian fauna composed, among other animals, of unicorns.

In India, Vincent de Beauvais placed the Indian donkey, the monoceron and the unicorn, three apparently different species. Marco Polo, who visited India and China at the end of the century XIII, described the unicorn of these lands as a plump gray animal, barely smaller than an elephant, which later authors rather associated with a familiar animal: the rhinoceros. Jourdan de Séverac, a missionary who left for the East in 1320, claimed to have heard from "reliable witnesses" that India was inhabited by real unicorns (unicornes veri>) and other fabulous beasts today such as griffins, cynocephalians and dragons. The 1398 German edition of Jean de Mandeville's travels included the unicorn among the animals that inhabit the garden of the abbey in the city of Hangzhou, south China.

The Myth of the Maiden and the Unicorn

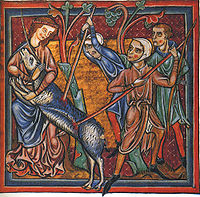

In The Physiologist, a compendium of the 2nd-4th centuries AD. C. which brings together descriptions of animals, plants and minerals inserted into an allegorical-religious scheme with a moralizing objective, the monoceros or unicorn appears from the beginning as a small, very fierce kid, which is hunted carrying near his dwelling a virgin girl; the animal throws itself onto her lap, she tames it, and thus takes it to the king's palace. animal bears on the forehead".

San Isidore, around the VI-VII centuries, integrated the legend into his Etymologies, but disregarding the religious interpretation offered in The Physiologist. The latter This work formed the common basis for all medieval bestiaries. Philippe de Thaon's, the first to be written in a Romance language, describes hunting as follows:

He is captured by a maiden, the way you will hear; when a man wants to hunt him or seize him with deceit, he goes to the forest, where the den of the animal is found, and leaves there a maiden with the uncovered breast; the Monkeys He perceives his smell, approaches the virgin, kisses his chest and sleeps before her, seeking death, comes to the man, who kills him during sleep or takes over him alive to do whatever he wants.

Philippe de Thaon's Beast.

If the maiden were not to become a virgin, Bartolomeo Anglico specifies that the unicorn will kill her for "corrupt and impure". The animal's attraction was associated with some kind of "smell of chastity", in such a way that Richard Fournival can say that the unicorn is "hunted by smell". However, according to the account of the Byzantine poet John Tzetzes, the strategy was successful even if it was a young man, dressed in women's clothes and heavily perfumed, who sat outside the beast's lair. When the wind blew, the unicorn came out of there and was stunned by the wonderful aroma, a moment that the hunters took advantage of to attack and cut off its horn.

Cyranides, another contemporary Greek work of The Physiologist, offers a possible contemporary precedent for the hunting story. There the rhinókeros is a deer-shaped quadruped that can only be captured "with the perfume and beauty of distinguished women". Scholars believe that the origin of this legend goes back to Indian history. of Rishyasringa, a man born with deer antlers who is seduced by a princess and taken to the king's palace, where he eventually marries her and inherits the kingdom.

Christian Symbolism

When the Septuagint Bible was composed in the III century B.C. C., the Hebrew word reʼém, which was intended to designate some type of large bovid that disappeared throughout the first millennium BC, was translated by monókeros, the one-horned beast mentioned by Megasthenes (Num. 23:22, 24:28; Deut. 33:17; Job. 39:9, and Ps. 21:22; 28:6; 77:69, 91:11). In the Vulgate, the most influential Latin edition of the Bible in the West until well into the 16th century, the Greek monokeros sometimes became rhinocerotis (eg: Num. 23:22, 24:8; Deut. 33:17 etc.) and sometimes unicornis (Ps. 21:22, 28:6, 91:22; Is. 34:7). in modern bibles):

Salva me ex ore leonis, et a cornibus unicorn humilitatem meam.Save me from the mouth of the lion, and deliver me from the horns of the unicorns.Psalms 21:22.

The spread of the Vulgate Bible led patristic-era exegesis to echo the animal designated in it as unicornis. In his commentary on Deut. 33:17, Tertullian says that the two horns of the bull are either end of the cross and "the unicorn the post erected in the center". object or in any other way than the one represented by the cross"., "God is a unicorn, Christ a rock for us, Jesus a cornerstone, Christ the man of men", and Saint Basil makes him "filius unicornium". For Ambrose, the origin of the unicorn is a mystery comparable to the virginal conception of Jesus.

In The Physiologist, Christ is the "spiritual unicorn", an animal whose appearance as a kid recalls the expiatory sacrifice of the cross and which, moreover, has the reputation of being "small", alluding to the humility of his incarnation, but also "very fierce," since death had no power to hold him; its only horn represents the unity between the Father and the Son, expressed by the latter in the Gospel of John as "I and the Father are one" (Jn. 10:30). Rábano Mauro also claimed the identification of the unicorn with Christ, based on passages like Jb. 31 and 39, Dt. 33 and Sl. 21 and 28, while Gregory the Great first equated the unicorn with the Hebrew people and, later, saw in it the image or prefiguration of the Messiah. Antonio de Padua's sermonary included the unicorn among the creatures with the horn curved towards back, symbol or image of hypocritical men who hide their sins under a cloak of false religious appearance.

From the beginning the hunt for the unicorn was interpreted as an allegory of the incarnation. For the author of The Physiologist, Christ was captured and sentenced to death having become flesh and dwelt in the womb of the virgin Mary. This formulation clashed with the unfortunate role that the maiden plays in the myth as the "deliverer" of the unicorn, a role that naturally could not be attributed to the virgin Mary. In the XII, Bishop Honorius of Autun expressed the mystery as follows:

Resting in the bosom of a virgin was taken by the hunters, that is, Christ was found in the form of man by those who loved him.Honorio de Autun.

Pierre de Beauvais' bestiary in prose (1175-1217) and Guillaume le Clerc's bestiary refer to Christ as the celestial unicorn who descended into the Virgin's breast and was seized by the Jews to be brought before Pontius Pilate. In Philippe de Thaon's version, the unicorn represents God and the maiden Saint Mary, who uncovers her breast —figuration of the Christian Church— so that the animal can kiss it —symbol of peace— and fall asleep before her —representing suffering death on the cross, for this is followed by his capture. The author of a Tuscan bestiary from 1468 imagined a radically different reading of the scene: the unicorn is a symbol of violent and cruel men to whom nothing can resist, but who can be defeated and converted by the power of God (like Saul of Tarsus).

Although the motif of the unicorn purifying water was generally discussed without any religious commentary, its Christological interpretation was all too obvious: the serpent poisoning the water is the devil sowing sin in the world, while the unicorn is the Christ the Redeemer who removes it.

The Unicorn and Courtly Love

Since the middle of the XIII century, the motif of the hunt for the unicorn was put at the service of a new orientation: the code of courtly love. In his Bestiary of Love, Richard de Fournival (1202-1260) speaks of love as a "cunning hunter" who put in his path a young woman on whose scent he fell asleep " and made me die a death like that befitting Love, namely, despair without hope of mercy", using the motif of the hunt for the unicorn as a comparison of his misfortune:

And I was hunted equally by the smell, just like the unicorn, who sleeps at the sweet aroma of virginity of the maiden.Richard de Fournival, Beast of love prose.

The poet king Theobald I of Navarre (1201-1253), although ignoring the details of smell and virginity, revealed the theme of the attraction of the knight to the maiden and his death "treacherously" in the lap from her:

I am like the unicorn,

That's amazed to look

When she contemplates the maiden.

He enjoys his torment so much.

That falls free in his lap;

Then they kill him for treason.

So they killed me.

Love and my lady, really:

They have my heart and I can't regain it.

The songs of Thibaut de Champagne, king of Navarre, song XXXIV, verse 1.

In the song Amor, da cui move tuttora e vene, the Sicilian poet Stefano Protonotaro (fl. 1261) uses the figure of the unicorn to develop the topic of love that he has his lover prisoner, who, at the vision of happiness that he has shown him, has surrendered and fallen into his power. The author of another anonymous sonnet of the Sicilian lyric also compares his state with that of other animals that, as a common feature, they cannot free themselves from the irresistible attraction that will lead them to death, and among them he mentions the unicorn, while in the epic poem Parzival, by the German Wolfram von Eschenbach, the lady he calls his friend a "fidelity unicorn" and envies his death.

The unicorn as a symbol of death

In the story of Saint Barlaam and Josaphat, Barlaam is a hermit sage who converts Prince Josaphat (Buddha) to Christianity by instructing him with a series of moralizing stories or exemplas. One of these exemplas is the story about a man who goes into the forest and flees from the unicorn that chases him by climbing a tree, where he hopes the animal will go on its way and leave him alone. Meanwhile, he collects the fruits without realizing that the roots are being worn away by two rodents, one white and the other black, that four snakes hold them below and that, in addition, the tree is next to a well where a dragon rests. In the end, this gullible man ends up falling into the pit and is devoured by the beast.

This oriental fable, which reached great diffusion in the medieval Christian West when inserted into other writings such as psalters, books of hours or sermonaries, exposes a symbolic scheme where the unicorn is a figure of death that persecutes man as a mortal who In other words, the two rodents symbolize the passage of time (the white one is day, the black one is night) and the dragon the entrance to hell, where man falls for putting love of earthly pleasures before the redemption of his soul..

Relationship with other animals

According to Saint Isidore's Etymologies, the unicorn often fights with elephants and wounds them in the stomach, a story undoubtedly taken from Pliny the Elder. Guillaume le Cler's Divine Bestiary specifies that it makes it "so strong under the belly with its cutting hoof like a blade, that it disembowels it completely". The fact that the unicorn uses its hooves to attack here is probably due to a translation error in the Isidorian text.

Another of the unicorn's enemies was the lion., when the unicorn is about to hurt him, he dodges it so that it hits the tree with force and his horn gets stuck in it, and then the lion "kills him very cunningly".

In a French text of the courtly genre, The Romance of the Lady with the Unicorn and the Handsome Gentleman with the Lion (1st century XV), the unicorn has been offered to the lady for her feminine virtues («Lady of the Unicorn») and will be the animal that protects and guides her, preserving her from all impurity and vice that can away from true love -referring to the traditional purifying properties of the horn. On the other hand, the knight ("Beautiful Knight") receives the emblem of the lion, a symbol of power, of sovereign and invincible force, for his virility and worth. The innovation of this novel involves the "reconciliation" of two traditionally enemy animals; During the journey to free the lady who was imprisoned in the castle of the traitorous Knight of the Golden Head, the unicorn and the lion are ridden by their respective masters and collaborate together for the same purpose, symbolizing the new ideal of perfection and absolute love where "opposite" elements come together in a superlative sense but, ultimately, complementary.

From the Renaissance to the 19th century

The Unicorn's Horn: Trade and Study

The supposed medicinal properties of unicorn horn made it one of the most expensive and famous remedies during the Renaissance. It could be consumed both as a powder (diluted in water) and as small pills, and was even valued as an amulet strapped to the chest. However, there was a shared suspicion that at least some of the specimens might be fake and sold fraudulently. seeking financial gain. For the renowned French explorer André Thevet, the small horns came from the rhinoceros, while the large pieces were forgeries made of ivory. The Swiss botanist Johannes Gessner, in 1559, had already suggested that ivory can be boiled to give it the appearance of a unicorn horn, and seven years later the Discourse Against the False Opinion of the Unicorn (1566), by the Venetian Andrea Marini, warned that these pieces were more numerous in England than anywhere else, probably because their origin was in some marine creature. For Thomas Bartholin, as he exposed in his treatise of 1645, the "teeth of the Greenland whale" are hollowed out and carved artificially to sell them as unicorns at very high prices, although he admitted that a few could come from of true lands and quadruped unicorns. This was the opinion shared by scientists such as Nicolaes Tulp (1652), César de Rocherfor (1668) and Olfert Dapper (1676). Another factor fueling skepticism was the great length of the alleged unicorn horns, too heavy for a horse-sized quadruped to carry on its head.

Knowledge of the narwhal certainly led to a significant drop in the price of the horn, but it did not definitively shake the belief in the earthly unicorn. Other authors did not see in it any properties other than those attributed to the horns of other animals well-known, such as the deer. So, to differentiate a "genuine" horn from a false one (belonging to another species), certain experimental tests were popularized such as:

- Dip the horn in water and check if this bubble.

- Enclose scorpions or any poisonous animal in a jar, along with the horn. If the sweat horn and the animals die at a short time, then it belongs to a unicorn.

- Trace a circle with the horn and place a spider inside it. If he cannot escape, the horn is genuine.

- Place an animal on hot coals and then the horn on top. If the horn is of unicorn, the animal will not burn.

- Give arsenic to two pigeons and one of them, also add some of the horn in the form of limestones or dust. If the one who ingested part of the suspicious horn survives more than his companion, the horn is unicorn.

However, the efficacy of these experiments was soon questioned. The French physician Ambroise Paré, in his famous 1582 treatise on the reality of the unicorn, explained that the bubbling water test could be passed by the horns of any animal —such as an ox or a goat— due to their porosity, while he attributed the exudation in the presence of poison to a fortuitous effect produced by the humidity of the air when it comes into contact with polished surfaces. To falsify the belief that it was useful as an antidote, Paré soaked the horn in water and then submerged a toad in it: the animal he was still alive three days later. In a later work he concluded that the idea of a universal contravenin is meaningless from the theory of the four humours, the same observation made by Andrea Marini in 1566 and by Dr. Jacques Grévin in 1567. In an effort to defend the existence of the animal and the properties of its horn, the Catalan doctor Catelan Laurent (1624) advocated the operation of the principle "like cures like": the virulence that is Concentrated in the unicorn's horn, contracted by the vermin on which it feeds, the infected waters where it drinks, and the unhealthy swamps that are its habitat, it is the one that fights the poison.

Stories of travel and exploration

Middle East

During his trip to the region of Arabia, in 1503, the Italian explorer Ludovico de Varthema believed he had seen two unicorns in a Mecca enclosure, apparently sent by an Ethiopian king as a pledge of alliance for the city's sultan The largest, a "proud and discreet beast", he described as the size of a yearling colt and a horn four palms long, the split hoof of a goat, the head and feet like that of a deer, the short neck and short hair hanging to one side. Idaith Aga, Suleiman's ambassador to Emperor Maximilian's court, would have seen entire herds of this animal. According to Paulus Venetus, the unicorns of the Basman kingdom enjoy wallowing in the mud, like pigs, and are almost as big as elephants, with the hair of a camel and the head of a boar.

Africa

In his Relation of an embassy to Prester John (1565), the Portuguese traveler Jodo Bermúdez indicated that a unicorn animal, similar to a small horse, inhabits the mountains of Abyssinia —Ethiopia— In this same region, the Italian chronicler Paolo Giovio (1485-1552) placed a "colt of an ashen color, with a goat's mane and beard, armed on the front part of his forehead with a polished two-cubit horn (...) and white like ivory, but variegated with warm colors". André Thevet mentioned unicorns in South Africa, the Cape of Good Hope and Madagascar, while for Luis del Mármol Carvajal, a Spanish traveler, the habitat of this animal was "the high Ethiopia, in the mountains of Beth or [of] the Moon". The Franciscan Luis de Urreta also located the unicorn in the mountains of the Moon —a way of designating the summits of the Upper Nile—, but he recognized that the inaccessibility of the place had prevented him from personally seeing any specimens.

In 1682, the Italian Capuchin Jérôme Merolla da Sorrento differentiated the European monoceros —which he believes has disappeared— from the unicorn he had observed in the Congo, a beast the size of an ox and, only the males, with a single horn on the forehead. According to him, the locals used this horn for its medicinal properties.

One of the most popular stories at the end of the XVII century and throughout the XVIII was that of the Jesuit priest Jerónimo Lobo. In 1672 he described a unicorn animal from Tonküa, in the province of Agau, kingdom of Abyssinia:

It has the size of a small horse, of brown hair almost black; the crin and the black tail, short and scarce hair (...) with a straight horn of five palms long, of a color that tends to the white. He still lives in the woods, he is a very fearful animal and barely ventures in open places. The peoples of these countries eat the flesh of these beasts like that of all the others that the forests provide.

Testimony of Jerome Wolf, quoted in Melchisédech Thévenot, Relations of several curious trips1672, volume IV.

Lobo tried to differentiate this unicorn from the rhinoceros, "which has two horns, not straight but curved", and his testimony was considered credible in the dictionary of Antoine Furetière (1690), who cited it along with sightings by Vincent le Blanc and André Thevet. The article on the animal in Diderot and d'Alembert's encyclopedia (1765), although referring to it as a "fabulous animal", took up the description of the Portuguese missionary word for word.

The presence of the unicorn in African lands was a rumor widely spread by modern travelers such as the French Pierre Delalande and Jules Verreaux, the British Francis Galton, the Germans Eduard Rüppel, Albrecht von Katte and Joseph Russeger, among others. publication of the Asian Journal of 1844, the orientalist Fulgence Fresnel did not rule out the existence of a variety of unicorn oryx in East Africa; He claimed to have seen from afar, on Mount Elba, an animal similar to a strong gazelle with a single horn in the middle of its head. Also the magazine The Athenæum, at the end of 1860, confirmed that Andrew Smith had collected a great deal of information about "a unicorn animal as yet unknown to Europeans", and months later, in 1862, he published a letter in which explorer William Balfour Baikie claimed that "the non-existence of the unicorn is not proven", although the creature "does not correspond exactly to the traditional English unicorn": the African natives had seen the skeleton of this animal "with a single long and straight horn" and even kept its skull. That same year, Claude Scheffer received from the Danqali tribe the testimony about a unicorn animal that inhabits "the thickest forests of the Abyssinian mountains"; they named it abu qarn, thus differentiated from the rhinoceros or baghal wahchi. "There is no doubt that such an animal existed," wrote William Reade in 1863, for whom the species it could be extinct or, more likely, had escaped from gunfire into the "vast unexplored and uninhabited forests of central Africa".

Curiosity led to the fact that monetary rewards were sometimes offered to those who presented a specimen of a unicorn. Thus, in 1793 the Dutch colonist Cornelius van Jong promised a reward of three thousand guilders to whoever brought him the live animal, and in 1838 a German newspaper offered one hundred talers for a live unicorn and fifty for a dead and well-preserved one, "so that, if this animal that we have talked about for a long time really exists, we may soon have a representative of the species."

India and China

The unicorn appears among the animals that the adventurer Thomas Coryat, in 1616, said he had seen in the court of the Great Mughal, in the city of Ashmere (eastern India), describing them succinctly as «the strangest beasts in this world ».

Later, at the beginning of the 19th century, British soldiers stationed in India claimed that the unicorn inhabited the valleys Himalayan highlands and the Tibetan plateau. "A horse with a horn in the middle of its forehead", coming "from far away", was the animal described to Captain Samuel Turner by the Rajah of Bhutan shortly before 1800, while B. Latter, a British soldier in eastern Nepal, learned from the natives of the existence of a supposed Tibetan unicorn, "very wild and seldom caught alive", similar to the "unicorn of the classics". In the middle of the century, the French missionary Evariste Huc declared that he had no doubts that the unicorn, "which we have long regarded as a fabulous being", really exists in Tibet and is represented in the sculptures and paintings of Buddhist temples..

America

In 1540, the Portuguese navigator Jean Alfonse de Saintonge reported that the natives of the Canadian coast believed that there were unicorns on it, and in the General history of the deeds of the Castilians on the islands and mainland of the Mar Oceano, from 1601, the chronicler Antonio de Herrera quickly commented on the existence of an animal the size of a horse and with a round horn on its head. However, the mythical unicorn never gained much space. in the New World. Francisco López de Gómara categorically stated that "there are no unicorns in our Indies, nor elephants".

Amphibious and two-horned unicorns

At the middle of the XVI century, accounts of explorers mentioning strange aquatic unicorns appear. The Portuguese doctor and naturalist García da Orta described in the region of the promontory of Buena Esperanza and that of Courantes a species of terrestrial animal very given to the sea, with the head and mane of a horse and, in the middle of its forehead, a movable horn with two spans long, which would have antivenom properties. Twelve years later, in 1575, André Thevet collected this testimony in his work Universal Cosmography, but giving the beast its own name: naharaph. Inspired by him or not, Thevet also spoke of another exotic animal that would inhabit the Moluccan islands, the camphur. It was a terrestrial beast, due to the split hoof on its front legs, but also It was amphibious, having webbed hind feet and surviving by hunting fish. It was the size of a deer, with abundant gray fur around its neck, and its characteristic feature was the three and a half cubit horn on its forehead, movable as could be. be the crest of a rooster. Thevet says that "some have convinced themselves that it is a kind of unicorn, and that its horn, which is rare and rich, is very excellent against poison".

The two-horned unicorn, pirassoupi or pirassoipi, was also described by André Thevet in his Universal Cosmography as a beast native to Brazil, of size and head similar to that of a mule, abundant fur like that of a bear but of a more vivid color, tending to fawn, and split hooves like those of a deer, armed on the forehead with two very long horns and without ramifications. These horns, "reminiscent of those of the esteemed unicorns", are submerged for six or seven hours in a water that, in this way, acquires healing properties. Since Thevet had not mentioned this creature in his 1557 work, Singularities of Antarctic France, it is most likely one of his later creations, perhaps based on the description, adorned with imaginary elements, of an Andean camelid seen in the distance.

Debate on the nature and existence of the animal

For most scholars of the late 16th century century, the unicorn and the rhinoceros were different animals. Prelate Juan González de Mendoza, upon his return from Cambodia, assured that "all those who have gone to distant regions and have observed a true unicorn know that it has nothing in common with the rhinoceros." The History of Animals de Gessner (1551) treated both animals separately and Ulysses Aldrovandi, in Of quadrupeds solipeds (1616), categorically stated that "unicorn is not rhinoceros" and "rhinoceros is not a unicorn", for the rhinoceros is more ferocious than the monoceros and has two horns—which is certainly true of the African variant, but not of the Indian variant.

In 1557, Giulio Cesare Scaligero reproached the neoplatonic mathematician and philosopher Gerolamo Cardano (1501-1576) for drawing «the monoceros with the name De subtilitate in his work De subtilitate of a rhinoceros, being that they are two very different animals": the rhinoceros more similar to a bull and the monoceron like a deer. Another testimony that confirms the differentiation of these two species in the European mentality is that of the Portuguese García da Orta, who in his 1563 work he stated that he had never personally seen a rhinoceros, but that the Bengals used its horn as an antidote, "having the opinion that it is the horn of a unicorn, although it is not"..

Michel Herr's Description of Quadrupeds (1546), which purports to bring together animals "well known" and "proven existence", includes the unicorn. A few years later, in 1551, Conrad Gessner publishes History of Animals in four volumes, a work considered the beginning of modern zoology, and comments that European authors had only heard about the animal, without ever having seen it. In addition, a point was highlighted that would be fundamental in the discussion that was brewing about the reality of the unicorn: the great discrepancy between its descriptions. The Discourse of the Unicorn (1582) by Ambroise Paré, which It was the first work entirely dedicated to refuting its existence and the properties of its horn with scientific arguments, both rational and natural, it found an immediate reply in an anonymous text called Response to Ambroise Paré's speech on the use of the unicorn (1583), where Paré was compared to Lucifer and the reality of the unicorn was defended based on the authority and tradition of the ancient authors. To this supposed authority, André Thevet opposed the little credibility that could be granted to Pliny the Elder when he spoke of fabulous creatures such as griffins and mermaids, so his testimony about the unicorn was far from infallible.

The disparity in descriptions was explained by proposing the existence of several species of unicorn. Catelan Laurent, in his History of the nature, hunting, virtues, properties and use of the unicorn (1624), collected eight types: rhinos, onagers or "wild asses", oxen and unicorn cows, unicorn horses, the camphur, deer and one-horned goats, half-deer and half-horse animals - inhabiting Finland - and the kartazonos described by Pliny. The latter, according to him, would be the authentic or proper unicorn, endowed with a black horn two cubits long and impossible to tame. For Caspar Bartholin, who published his dissertation on the unicorn in 1628, the species were: oryx, camphur, the "unicorn of the northern seas" - probably the narwhal -, the unicorn ox of the Indies, the Indian donkey, the unicorn horse, the rhinoceros and the "real monoceros". Illustrations of eight species given Latin names Two of them, clearly inspired by the Camphur, accompanied John Jonston's brief description of the animal in his General History of Quadrupeds (1652). Pierre Pomet listed five in History medicines (1694), including camphur and pirassouppi, but avoided ruling on the existence of the quadruped.

Religious censorship also reached the disbelievers of the animal. In 1607, Edward Topsell lamented that there was "a secret enemy at work in the degenerate nature of man, who closes the eyes of God's people to prevent them from seeing the greatness of his works". And if almost sixty years earlier the zoologist Gessner had proposed With caution the idea that the unicorn could have become extinct in the Universal Flood, for the Jesuit Athanasius Kircher this position was equivalent to "denying divine providence" and "not fearing blasphemy".

Interest in this animal began to wane from the middle of the XVII century. In his translation of From the description of Africa to French (1678), Nicolás Perrot d'Ablancourt commented negatively on the mentions of the "grey unicorn of Ethiopia", lamenting that the author had told "fables" about the fauna of the continent. The Explanations of the figures found on the terrestrial globe of Marly (1703), by François Le Larg, called the unicorn a "pure chimera", since "no two agree in the description that they make of it". >Natural History of Cetaceans by Étienne de Lacepède. Other illustrated works displayed the same skepticism:

Moderns doubt for reason that once on Earth there has been an animal called unicorn, and take all that the ancients said as pure fables.

François-Alexandre Aubert de La Chesnaye Des Bois, Reasoned Animal Dictionary (1759).

In the annotated translation of Pliny's Natural History (1771), Jean Étienne Guettard opines that «the unicorn is not an impossible animal», although the ancient descriptions of it were made by «authors that they seem little versed in natural history." Just as cautiously, Jules Camus merely noted that "this animal is utterly unknown to modern zoologists." Jean-François Laterrade, a Bordeaux professor of natural history, published in 1825 a Notice in refutation of the non-existence of the unicorn, an article in which he borrows the —already old— argument that each marine animal (such as the narwhal) corresponds to a terrestrial one. The Baron de Cuvier He definitively denies the existence of the unicorn in his commentary on the work of Pliny (1827), but assumes that there may be examples of unicorns other than the rhinoceros, either by accidental mutilation or by birth defect. In contrast, for David Livingstone the unicorn " it can't be co "considered a fabulous animal, even if our national representation may be fanciful", and suggests that it is a species halfway between rhinoceros and light horse, inhabiting tropical Africa. The Dictionary of Natural History, constantly republished between 1846 and 1872 by Charles Orbigny, echoed the multiple testimonies of unicorn antelopes from Africa and Tibet to argue (with great ambiguity) that "the existence of a single-horned animal in the midst of the head is not impossible":

Of all the observations we have just presented, the existence of unicorn cannot be completely denied (...) we have to believe that there is an animal more or less like the one indicated by the ancients and some modern travelers (...) In short, let us say that the unicorn as the ancients imagined it does not exist in nature, and that it is possible that this animal is only a kind of antilope.Universal Dictionary of Natural History (1872), edited by Charles D'Orbigny.

The existence of unicorn antelopes in Tibet, a rumor fueled by British soldiers stationed in India, was also defended by Ferdinand Hoefer in his work History of Zoology (1873), while for the French Illustrated Dictionary (1864), although it is not unimaginable that such an animal exists, it is certainly "very improbable". For its part, the Dictionary de Ciencias, Letras y Artes (1854) collected the description from the classical sources, but noting that "scholars and scholars deny the existence of this quadruped". This appeal to academic consensus reappeared in the Dictionary of the French Academy (1879), for which, "according to the most accepted opinion", the unicorn is a fabulous animal. This animal "has no real existence" in the Dictionary of the language French (1863) and is "fabulous" or "probably fabulous" in Dictionary de Bescherelle (1887) and Dictionary Larousse (1873), r respectively. Works such as Saint-Clavien's Dictionary of Zoology or Natural History (1863) and Élisée Reclus's New Universal Geography (1888) simply avoided any mention of the animal.

20th century and 21st century

Since the end of the XIX century, the unicorn has been a typical creature of fantasy and magic stories. It is the protagonist or appears in written works such as Through the Looking Glass (1871) by Lewis Carroll, The Unicorn of the Stars (1907) by William Butler Yeats, The Daughter of the King of Elfland (1924) by Lord Dunsany, The Last Unicorn (1968) by Peter S. Beagle —where the hero is a unicorn, the last of its kind, who must escape from those who want to capture or destroy him— The Lady and the Unicorn (1974) by René Barjavel and Olenka de Veer, the Sign of the Unicorn (1978) by Roger Zelazny —where the protagonists meet a lonely white unicorn in a forest, an animal with golden hooves and horns—, the Unique manga (1976-1979) by Osamu Tezuka, The Black Unicorn (1987) by Terry Brooks —where the animal is evil—, the novel The Curse of the Unicorn, within the trilogy The Phoenix Cycle (1990) by Bernard Simonay and even the famous literary series Harry Potter (1997-2007), by J. K. Rowling. On television, She-Ra and the Princesses of Power features Éclair, Adora's horse who transforms into Fougor, a winged unicorn endowed with speech. The American animated series Princess Starla depicts the teenage knights of Avalon riding unicorns. In My Little Pony, unicorns are one of the three main races that populate the world of Equestria, along with ponies and pegasi.

His modern imagery moves away from medieval heritage, to become that of a tender “magical” white horse with a single horn on its forehead. He inspires an abundant production that includes toys, decorations for children's rooms, posters, calendars or even figurines, especially aimed at a female child audience. He is also present in role-playing games like Dungeons & amp; Dragons, where there are different kinds. On the internet, the parodic religion of the invisible pink unicorn seeks to highlight the difficulty of refuting beliefs in phenomena that are outside human perception. For Bruno Faidutti, this presence of the animal in popular culture means that today it is "better known than the platypus or the dodo, and most of us could describe it infinitely more accurately".

If no one believes in the physical existence of the unicorn anymore, the belief in "spiritual" unicorns continues today in the New Age mainstream. The American esotericist Deanna J. Conway proposes to invoke a unicorn as a guide to the land of the fairies to obtain spiritual growth and an improvement in one's moral values. Diana Cooper and Tim Whild presented the unicorn as an intangible guardian angel, a "energetic being" and a "spirit guide". Adela Simons claims that unicorns live on a different vibrational frequency from humans, and that their appearance in the Bible is proof of their existence.

Heraldic Unicorn

According to Michel Pastoureau, until the 14th century the unicorn remained largely absent from coats of arms. His kid silhouette gave way to an equine figure at the dawn of modernity, although retaining the characteristic goatee. He was usually depicted in white and was a symbol of strength, modesty and virtue. "His nobility of mind is such that she would rather die than be captured alive; the unicorn and the brave knight are identical", said John Guillim's treatise on heraldry (1610). Marc de Vulson de La Colombière commented, in 1669, that the unicorn is "enemy of poison and unclean things; it can denote purity of life and serve as a symbol for those who have always fled from vices, which are the true poison of the soul." Bartolomeo d'Alviano, captain in the service of the Orsini, took advantage of this symbolism by embroidering a unicorn that plunges its horn into a water fountain, accompanied by the legend "I hunt the poison". According to Bruno Faidutti, one of the oldest examples of the heraldic unicorn must be the coat of arms of the Knight of the Round Table, Gringalas el Fuerte, who wore as his coat of arms "a sable, a silver unicorn, horned and nailed with azure".

Today, the unicorn is present on the coats of arms of many countries. For example, the coat of arms of Great Britain is supported by a unicorn, representing Scotland, which carries two as tempters (see: Coat of Arms of Scotland), and a lion, representing England. Their combined presence symbolizes the imperial union of the two crowns In his work Through the Looking Glass, Lewis Carroll quoted an English nursery rhyme that recalls the origin of these gun stands: “The lion and the unicorn fought for the crown. The lion beat the unicorn for the whole city. As tempters, both animals reappear on Canada's coat of arms, while in the Lithuanian armorial (presidential version only) the unicorn holds the shield alongside a griffin, another fantastical beast.

In France, the animal is featured on the coat of arms of the city of Amiens and emblem of the Amiens Sporting Club, a professional soccer club based in the same city. It is represented in the logo of the club, which plays its home games at the Stade de la Licorne ("Unicorn Stadium"). The unicorn is also present in the coat of arms of the Norman city of Saint-Lô, and in that of the Alsatian city of Saverne, which inspired a famous brewery.

With the development of printing, the unicorn became the animal most frequently depicted on paper watermarks, and the most common after the phoenix on printers' brands and posters across Europe. Bruno Faidutti believes that, in In this context, the animal symbolizes the purity of the paper and, therefore, the purity of the printer's intentions.

Other World Cultures

Muslim bestiaries collected various one-horned creatures. The most important of these is the karkadann or rhinoceros (Arabic: كركدن), which Abū Rayḥān al-Bīrūnī (973-1078) describes as being buffalo-like in composition, with black, scaly skin, a short tail, low-set eyes, and a single horn., on the upper part of the nose, which bends upwards. Later authors changed the position of the horn from the nose to the forehead of the animal and added medicinal and anti-venom properties similar to those of monoceros of Ctesias. Another is the shâd'havâr (Arabic: شادهوار) or āras (آرس)—first described by the Arab scholar Jabir ibn Hayyan in the VIII—, a quadruped that would live in the country of Rūm (Byzantine Empire) endowed with a horn with 42 hollow branches that, when the wind passes through them, it produces a pleasant sound that makes the animals sit and listen around it. Finally, mention can be made of Al-Mi'raj (in Arabic: ٱلمعراج), an animal shaped like a rabbit, with yellow fur and a single black horn, which is born from its head, and which would live on a mysterious island called Jazirah al-Tennyn, within the confines of the Indian Ocean.

The animal from Chinese mythology called the qilin, a gentle, horned quadruped commonly associated with the giraffe, has been identified as a unicorn, although this is imprecise because it has also been depicted with two horns. In the Shuowen Jiezi, a work from the turn of the II century, the xiezhi is described as "a strong beast with only one horn". that he could distinguish the innocent from the guilty and punish the latter, piercing him with his horn. Other unicorn animals, such as the huānshū, the bó, the bómǎ and the zhēng, are mentioned in the Classic of Mountains and Seas (Shan Hai Jing), a compendium of fantastic descriptions of the country's geography and fauna.

The Chiloé mythology, of the inhabitants of the Chiloé archipelago (Chile), speaks of the camahueto as a beast similar to the sea elephant, equipped with a single horn whose fragments the sorcerers can "seed" to generate a new specimen. This birth would imply the formation of a lagoon around it, which grows until the camahueto decides to move to its final home, the sea, causing landslides in the ravines and the formation of a small stream.

Contenido relacionado

Mu (lost continent)

Erinyes

Greek mythology