Typography

The typography (from the Greek τύπος [típos], 'blow' or 'imprint', and γράφω [gráfο], 'to write ') is the art and technique in handling and selecting type to create print jobs.

The typographer Stanley Morison defined it as:

Art of having the material printed correctly, according to a specific purpose: to place the letters, to distribute the space and to organize the types with a view to lending the reader the maximum help for the understanding of the written text verbally.Morison (1936)

The printing method that makes use of types is also called «typography» or «typographic printing» (letterpress) as opposed to other existing methods, such as offset printing, digital printing, etc..

Type Definitions

Typography is called the task or trade and the industry that deals with the choice and use of types (letters designed with unity of style) to develop a printing work, which refers to the elements letters, numbers and symbols belonging to printed content, whether in physical or digital support.

It is important to keep in mind what you want to communicate, because this will define which type is the most representative for the intended intention.

- Microtype or Detail typography

- The term Mikrotypografie (‘microtypegraphy’) was first applied in a speech given at the Munich Type Society. It has since become widespread in specialized literature. However, it can also be replaced by an English word, Detailtypografie (“detail typography”). It includes the following headings: the letter, the space between letters, the word, the space between the words, the interlinear and the column. It has three important functions: the visual weight, the interletrado and the interlinear.

- Macrotype

- The macrotypeography focuses on the type of lyrics, the style of the letter and the body of the letter.

- Editing typography

- It brings together the typographical issues related to families, the size of the letters, the spaces between the letters and the words; intertype and interline and the measure of line and column or box, that is to say those units that grant a normative character.

- Creative typography

- It contemplates communication as a visual metaphor, where the text not only has a linguistic functionality, and where sometimes it is graphically represented, as if it were an image.

History

- Before the invention of the printing press, see: Manuscript and Calligraphy.

Gothic and Renaissance

The printing press in Europe developed at the height of the Renaissance; however, Johannes Gutenberg's early printings, such as the 42-line Bible, used a type style from the Gothic period that was called texture.

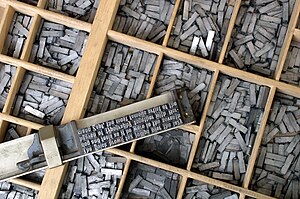

The first movable type, invented by Johann Gutenberg, and the round or roman typeface that followed in Italy, imitated the handwriting style of those countries in vogue at the time.

Although the Chinese are now known to have experimented with ceramic movable type as early as the 11th century, Gutenberg is credited as the father of movable type. He lived in Mainz (Germany) and was a goldsmith by trade, but he acquired technical knowledge about the art of printing. Impressions from hand-carved woodblocks had already been made many years before.

In 1440 he began a series of experiments that, ten years later, resulted in the invention of printing using movable type. He used his knowledge of existing technology and materials—the screw press, oil-based inks, and paper—but it was the manufacture of type that he devoted much of his effort to.

As a goldsmith, he was well versed in shaping, mixing, and casting metals, which enabled him to develop a method for making type. It was about engraving each character in relief in reverse on a steel die that was embedded with a mallet in the die (a copper bar). The die was placed in the matrix, a master mold to cast each letter, according to a process called justification. The matrix was then placed in an adjustable hand mold onto which an alloy of lead and antimony was poured, thus modeling each type.

The visible fruits of his labors are the 42-line Bible, in 1445, the oldest book printed in the Western world, although he printed Indulgence of Mainz the year before, for which he used a cursive style of the Gothic letter called bastard.

The first round typefaces to appear in Italy between 1460 and 1470 were based on humanist handwriting. A renewed interest in the Carolingian minuscule had brought about a refinement in its design. The result was the final project for the first Roman type.

After 1460, leadership in the development of movable type shifted from Germany to Italy, the artistic center of the Renaissance. In 1465, in Subiaco, near Rome, Conrad Sweynheym and Arnold Pennartz, two Germans who had moved to Italy, influenced by the work of Gutenberg, created a hybrid type, a mixture of Gothic and Roman features. In 1467 they moved to Rome and by 1470 they had created a new set of letters based on the humanist script.

Meanwhile, in Venice, in 1469, the da Spira brothers created another Roman type superior to the previous one. Despite this, in 1470 Nicholas Jenson created a typeface that surpassed all those designed at the time in Italy and that he continued to perfect. He created a new one six years later, known as white-letter roman, used for printing Nonius Peripatetica. Since then, Jenson's proportions have served as an inspiration for type designs.

Although the predominant style in Italy was Roman, it was not the only one. Even Jenson continued to produce books in Gothic script, as did many others. In 1483, unusually, the German Erhard Ratdolt printed Eusebius using Gothic and Roman script together.

During the Middle Ages, book culture revolved around Christian monasteries, which could be said to serve as publishing houses in the modern sense of the term. The books were not printed, but written by monks specialized in this task who were called copyists. They carried out their work in a place that was in most of the monasteries called the scriptorium, which had a library and a room with a kind of desks similar to the lecterns in churches today. In this place, the monks transcribed the books of the library, either by order of a feudal lord or another monastery.

During the Gothic period, Europe gradually returned to an economic system dependent on the cities, and not on the countryside as it was traditionally during most of the Middle Ages. This determined the birth of the guilds, which gave way to a greater production of books. The books, usually religious, were commissioned by patrons given to a guild of book artists, who had trained specialists in lettering, decorative capitals, letter decoration, galley proofing, and bookbinding. As this is a completely handmade process, a 200-page book could take 5 to 6 months, and approximately 25 sheep skins were required to make the vellum where it was written and illustrated with egg tempera, gouache and a primitive oil form.

The cities that grew the most during the Gothic period were those in northern Europe, such as Paris, London, and a large number of German cities, which were the first to adopt the guild system. In addition, the city determined the birth of universities, which increased the demand for manuscripts and raised the need to find a new, massive and cheaper way of producing books.

Techniques

Paper reached the West following the caravan routes that came from the Far East, in Asia, towards the Mediterranean Sea, until it reached the Arab world, and these, in turn, took the invention to Europe during the Arab invasions who came to Spain.

In a short time, around the middle of the 14th century, the first paper mills spread from Spain to France, Italy, Great Britain and Germany. The same path that paper took, so did the woodcut, another Chinese invention. The first manifestations of this printing system can be seen in card games and religious imagery. Because these were the first designs to be introduced into an illiterate culture, they represented the first manifestation of the democratization of the art of printing in Europe. These images were loaded with signs and symbols that forced a logical deduction. The xylography allowed the books to be within the reach of the common people, which, for the most part, was illiterate. For this reason, the block book had very little text and many illustrations, which were understood by anyone, unlike the text, which needed the literacy of the population.

This system, however, was still quite expensive, since it took a long time to engrave each letter and each illustration on wood, which meant that they were very short books, approximately 30 to 50 pages.

The first block books were printed with a hand stamp and sepia or gray ink, later replaced by black ink. After the text and illustrations were printed, they were colored by hand using the same technique used in Gothic manuscripts.

Some engravers who made block books, trying to simplify their work, tried to engrave each letter independently to use it several times in different books, but since wood is a very malleable material, the letters deformed after a few impressions. In the mid-15th century, a new invention emerged that received different names, including "movable type printing system", "typography" and "printing".

The first to carry out a printing process using metal movable type in the West was the German Johannes Gutenberg, who produced his first prints between the years of 1448 and 1450. It should be noted that, although the development of this printing process is mainly European, it was produced thanks to certain changes that occurred in medieval Europe:

- The Arab invasions of the Hispanic peninsula produced the encounter of two cultures, which stimulated the production of ideas in European medieval society. Thanks to this meeting, Europe had the first contacts with new ways of thinking that were linked to new sciences such as algebra, the Arab mathematical system and new scientific models.

- The progressive trade of Europe with the far east, brought with it new materials and inventions such as compas, paper and ink, the latter two of paramount importance for the development of modern printing systems, since for the time, in Europe, editorial production was based on raw materials such as vitela (piel) and inappropriate mineral-origin paints to print on paper.

- In establishing new commercial routes, it is almost certain that new techniques had come to Europe, such as the oriental reproduction systems among which the engraving and serial printing are counted with wooden blocks, very similar to the printing system by mobile types, but that it did not develop massively in the far east due to the pictographic writing system of these cultures.

This is how Gutenberg adapted a press, and cast thousands of metal movable type, which could be adapted in the press by means of a box called a typeface. In medieval block printing, light water ink extracted from oak galls was used, which was very well absorbed by wood, but in metal type it ran or smudged. To produce a thick, sticky ink, Gutenberg used boiled linseed oil, which he then colored with smoke pigment. The only thing that was done by hand in the typographic printing was the design of the capital letter, and the application of its color.

In illuminated manuscripts, the books had a generous amount of images that were gradually suppressed from typographic books due to the technological impossibility of casting an entire image in metal at the time; Due to the fact that the production of an illuminated manuscript was extremely expensive, block and letterpress printing made it possible to lower these costs, thus making writing, as well as information, spread and produce changes of thought in Europe, which would bring reforms., counter-reforms and revolutions.

The first Roman, classical or serif font families

By 1500, Gutenberg's invention had been so widely disseminated that there were already approximately 1,100 printing presses in operation in Europe. In the Germanic countries the most used typeface was the fraktur (although the type used in Gutenberg's first Bible was "texture"). Unlike in Germany, in southern Europe the custom in the Middle Ages was to use the Carolingian minuscule next to Roman square capitals adapted from inscriptions found in the ruins of the Roman Empire, such as Trajan's Column; For this reason, this style of writing served as a model for the first Italian printers to create the classic typeface families or with serifs (also called "hawks" or "remates"). The first typeface with serifs appeared in the year 1465, later typographers and printers such as Nicolas Jenson and Aldo Manucio perfected these first fonts, making them more stylized and refined, as well as including a new typeface called "italics", which was taken from the chancellery calligraphy of the time; Currently, this style of font is called "italic" (for the country of origin) or "cursive", and it is used to highlight words chosen by the editor, foreign words and quotes in a text.

These early Roman typefaces, classical or serif, were given the name Venetian style, since the main Italian printers that produced them had been established in the city of Venice.

In France, notable typographer and printer Claude Garamond, who created between the 1530s and 1550s a French typeface family based on the Venetian style, which over time became the standard of his time and later.

Industrialization, 19th century: linotype and monotype

During industrialization improvements were made in almost all tasks related to typography: in type design Linn Boyd Benton patented in 1885 the pantographic recorder for making dies and punches; in composition two typesetting machines were invented, the monotype in 1886, where each letter of the mold is cast in relief separately, and the linotype in 1887, where each entire line is cast separately (hence its name), and at the end of printing each line is returned to melt to create new lines.

The artistic movements are closely related to typography and its design are: Futurism, Dadaism, Russian Constructivism, De Stijl movement and Suprematism.

Photocomposition

After the Second World War, the first steps were taken in making machines that would allow mechanical typesetters to be replaced by photographic systems, but it was not until 1956 when the first phototypesetting machine was marketed that improved the traditional linotype and monotype types.

In the 1960s, the use of cathode ray tubes increased productivity and had a great impact on the printing industry.

Digital age: TeX, PostScript, desktop publishing

PostScript is a language that encodes descriptive information, regardless of resolution or system.

Type characteristics

- ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü

Anatomy of the letter

Parts that make up a type:

- Height of the upper case: it is the height of the upper case letters.

- Height of the x: height of lower case letters, tiny letters, excluding ascendants and descendants.

- Ring: it is the closed curl that forms the letters "b, p and o".

- Ascendant: asta that contains the letter of low box and which stands above the height x, such as the letters "b, d and k".

- Asta: main trait of the letter that defines it as its most essential form or part.

- Mounting boots: are the main or oblique handles of a letter, such as in "L, B, V or A".

- Wavy or spine: it is the main feature of the capital letter "S" or "s".

- Cross-section: horizontal trait of the letters "A, H, f and t".

- Brazo: terminal part that is projected horizontally or upward and that is not included within the character, as it is pronounced in the letters "E, K and L".

- Cola: an oblique pendant that forms some letters, such as in the "R or K".

- Descendant: asta of the lower case letter that is below the base line, as it occurs with the letters "p and g".

- Inclination: angle of inclination of a type.

- Baseline: the line on which the height is supported.

- Sheep: termination or terminal that is added to some letters, such as "g, o y r".

- Reba: space that exists between the character and the edge of it.

- Serifa, remate or grace: it is the stroke or end of an asta, arm or tail.

Classification of types

Fonts are classified through styles by their shape and also by the time they were designed.

Historical classification

The first movable type created by Johannes Gutenberg imitated the handwriting of the Middle Ages. For this reason it is not surprising that the first fonts that began to merge were the Gothic letter or fraktur in Germany and the humanistic or Roman (also called Venetian) in Italy. The evolution of typographic design has made it possible to establish a classification of fonts by styles, generally linked to the times in which the font families were created.

- Humanistic or Venetian

- It is known with this name to those first types created in Italy, shortly after the printing was invented; they imitated the Italian calligraphy of the time. In the same way, those foundries are called humanistics that without being of this age (XV century) are inspired by them. It is created on the outskirts of the city of Venice, Mestre. Generating great controversy about the exact origin of this type of calligraphy.

- The guy. sans serif is based on the proportions of the Romans. The inscriptional capitals and the low-box design of the Romans of the XV–XVI centuries. They are not monolines and are a version of the Roman but without serifas. Some examples of these types: Gill Sans, Stone Sans, Optima.

- Edward Johston, a photographer of the time, with his creation in the type of Palo Seco for the London Metro in 1916 meant a great step regarding the usual characteristics until then present in these types.

- Ancient or Roman

- Historically, they are called ancient types to which Aldo Manucio used in his Venetian printing from 1495 and all those who have been later made but have influence on these or are subsequent adaptations. Like humanistic typographical families, they have a great calligraphic influence but are more refined, because the matrice carvers had acquired more skill in the making of the typographic pieces.

- Transition or real

- They belong to the first Industrial Revolution (England).

- The main characteristic of these is that in the same line several characters enter, the apex is in the form of a drop, and the tiny ones are higher than in the case of humanists and garaldas.

- These characteristic forms correspond, too, to which they are used in the famous TIMES newspaper (in which they use the Times New Roman font created by Morrison). The narrow and high letters achieve a good visualization for the reader and in the same line enter several characters, this would help them to fit the information perfectly.

- Modern

- In 1784 Firmín Didot created the first modern type. This possessed formal characters such as a deep modulation and contrast between the strokes and a crisp auctions that at another time could not have carved. This style was improved with the creation of the Italian Bodoni and was used as a text run until the early nineteenth century.

- Egyptians or Mechanics

- They are those of great auctions depart from traditional traits like the calligraphics. Also called machines, they exaggerate the auctions of the modern ones producing a shocking look, discovering firmer strokes. The contrasts of the stroke are variants, the mechanical types are characterised by their monolineal structure and ashted traits, they also perceive simplified geometric shapes and in general a single thickness in the stroke, the serif is almost the same thickness as the sticks of the letters. They emerged from industrialization in the late 18th and early 19th century. Examples: Serifa, Rockwell, Clarendon.

- Dry stick or sans serif

- Those who don't have auctions. A date on which the first ones appear could not be set, since in some catalogues there appeared letters of high box without auctions already in the XIX.

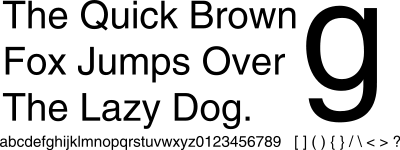

Classification by shape (serif/sans-serif)

One way to classify letters is by whether or not they have serifs. It is understood by serifs, or finishes, the small lines that are found in the endings of the letters, mainly in the vertical or diagonal strokes. The usefulness of the serifs is to facilitate reading, since they create the illusion of a horizontal line through which the eye moves when reading.

Letters without serifs or sans-serifs are those that do not have any type of termination; they are generally considered unsuitable for a long text since reading is uncomfortable since there is a visual tendency to identify this type of letters as a succession of consecutive vertical sticks.

For this reason, serif letters (also called romans) are used in newspapers, magazines, and books, as well as in publications containing long texts. The letters without serifs or sans serifs are used in headlines, labels, announcements and publications with short texts in the valiante style. Given the appearance of electronic media, sans-serif letters have also become the standard for publishing on the web and electronic formats, since serifs end up distorting the type due to the low resolution of the monitors. This is because small curves are very difficult to reproduce in screen pixels.

Monospaced/Tight

We can also classify them depending on their use in a more colloquial way as currently used by typographers on typography machines with Heidelberg de Aspas or Minerva

Those who print

They are the letters or types, borders, signs, numbers..., in short, all the characters that can be printed.

The Whites

They are pieces of lower height than the types and are used to create spacing, between words, spaces, ingots or impositions.

Typometry: typographic measurements

It is called typemetry to the typography area that aims to measure the typographical signs and their spaces. Traditionally its definition corresponded to the measurement of the metal types used in the Manual Type Composition that was performed by type metal letters. By extension, it is currently used to measure everything related to typography, even if it is in digital support or its paper print.

This form of measure is based on the old duodemic measurement systems, but which, depending on the geographical or historical area, take different measures as a starting point. Traditionally, the measurements of metal types and typographic documents were performed with the help of a tool called a typometer, but nowadays most print measures are done in preprint, directly on the computer.

Currently, the most commonly used measuring unit in Typography is the PostScript point, also called the DTP Point (Digital Technology Point).

Until the emergence of digital typography, the most used system was the so-called Anglo-American point, based on the Anglo-Saxon inch (2.54 mm).

The minimum unit is known by point, and in the case of the Anglo-American system, it is equivalent to 0.351 millimeters.

Each 12 stitches set the measuring unit known for itch, while every 12 didot points set the unit known as the cicero.

Its implementation in the printing press allowed it to have a system of exact measures for small lengths, since its unit is based on integers and not on decimal fractions, and therefore it was useful to build forms that required its regular account of the elements involved in creating a typographical form.Metric

Most scripts share the notion of a baseline: an imaginary horizontal line on which characters rest. In some scripts, there are parts of glyphs that go below the sloping baseline that spans the distance between the bottom line and the lowest descending glyph of a typeface, and the part of a glyph that slops below the bottom line has the well-known descendant. Conversely, rise spans the distance between the baseline and the top of the glyph reaching farthest from the baseline. Rise and grade may or may not include distance added by accents or diacritical marks.

In the Latin, Greek, and Cyrillic scripts (sometimes collectively referred to as LGC) the distance from the bottom to the top of glyphs may be referred to, from the lower case (bad line) as x-height, and the part of a glyph that rises above x-height as ascender. The distance from the baseline to the top of the ascender or regular capital glyphs (cap line) is also known as the cap height. The height of the ascender can have a dramatic effect on the readability and appearance of an ascender. foundry. The ratio between the x-height and the height of the rise or cap often serves for its characterization. To measure the height of the letters, the typometer is used, which is a graduated rule where centimeters and millimeters appear on one side, and ciceros and points on the other.

Typographic elements

Justification or alignment

Justifying or aligning a text is the way to accommodate the lines in the box. That is to say, it is the way in which they are aligned with each other, leaning on one side, in the center or achieving a whimsical shape. Taking into account that the word "box" appeals to the ancient method of accommodating types (letters) in a wooden container to form columns, we can clearly imagine the lines leaning to the left in a column, for example.

The names given to the ways of justifying a text vary occasionally between the different countries, but we can say that the most common are:

- In block, block or drawer, which are those in which the lines go side by side in a column.

- Aligned or Locas on the left, those that support the left without the requirement to reach the end of the column.

- Aligned or Locas on the right.

- In pineapple or lined to the center, being those that focus one under the other.

Nowadays, text columns are also applied in whimsical ways either by following the outline of a figure or by creating a figure out of themselves. Creativity has developed portraits formed with the text of the character's biography and an endless number of applications that are commonly seen in legible or practically illegible deformations, seeking to attract the observer's attention. Justifying is then, simply giving any format to the text in question.

Spacing (tracking)

Spacing or tracking refers to the space that exists between each pair of words in a text in relation to the square or width and height of the body used.

Width or thickness

A second way to classify the letters is according to the width or thickness, that is, the space that each letter occupies horizontally. From the beginnings of writing and calligraphy and of course typography, the first teachers noticed that not all letters were the same in width and for this reason, the space between each one of them should vary so that reading was fluid. and balanced. Contrary to this reasoning, the letters on typewriters each occupied the same space, so that different spaces were seen in the text between them. Taking into account that not all letters have the same width: An "m" took up all the space, while an "i" took up much less. If an "i" and an "l" appeared next to each other in the text, the space between the two was very large, while if an "m" and an "o" appeared next to each other, the space was very small. All this resulted in considerable discomfort in reading and, for example, in the case of headlines or labels.

Here is an example of each of the two typefaces:

- Lorem ipsum with Arial (compensated):

- Lorem ipsum pain sit amet, consectetur adipisicing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua.

- Lorem ipsum with Courier New (non-compensated)

- Lorem ipsum pain sit amet, consectetur adipisicing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua.

Leading

As the word says, line spacing is the separation between lines. It is measured in points.

Digital Typography

Today's computer word processors have a wide range of fonts—also incorrectly called, due to English influence, font—both one type and another.

The font Times New Roman was originally designed for the English newspaper The Times. This type of font achieved great legibility and excellent use of space, which is why it was immediately used in print media and, above all, in the press. The great popularity of Times New Roman is a point in its favor for its use even in electronic media, but for long texts in electronic format it can cause fatigue, precisely because the way in which the eye perceives The borders in this format are just the opposite of those on paper, since due to the low resolution of the monitors, the serifs end up distorting the outline of the glyph. This is because small curves are very difficult to reproduce in screen pixels. Obviously, the spacing between lines also influences the readability of an electronic text. For letters and emails both fonts are appropriate, while for reports and contracts (usually long) serif fonts are more appropriate.

Typography for web

It is possible to affirm that all the types whose design is the same or similar to the classic Latin (Roman) types are those that offer the best readability. Until now, the type that offers the maximum legibility in printed documents is the Times New Roman designed by Stanley Morison in 1932 to be used especially for the London newspaper The Times.

However, for the web there are those who consider that one of the best font families is Verdana, because it does not have serifs that are distorted, which is why it is one of the legible ones even at tiny sizes on monitors.

Computer fonts

The main formats used for fonts in computing are: PS, True type and OpenType.

Teaching

Little is known about the effect of typography on learning, although subjective preferences for certain letters, both in size and color, have been documented. These characteristics influence the comfort when studying.

Studies in Spain and Latin America

- Escuela Superior de Diseño en Madrid, Spain

- MT-UBA, Master's Degree in Typing. University of Buenos Aires, Argentina.

- Degree in Design and Production. Mexico City, Mexico.

Contenido relacionado

Within Temptation

Disney (disambiguation)

Abstract expressionism