Tycho Brahé

Tycho Brahe ![]() listen (?·i) (Thyge Ottesen Brahe; Knudstrup Castle, Scannia; December 14, 1546 - Prague, October 24, 1601) was a Danish astronomer, considered the greatest observer of the sky in the period prior to the invention of the telescope. His original name, Thyge Ottesen Brahe, in modern Danish is pronounced [шtsy mark ◆ diary.ا. εb.に].

listen (?·i) (Thyge Ottesen Brahe; Knudstrup Castle, Scannia; December 14, 1546 - Prague, October 24, 1601) was a Danish astronomer, considered the greatest observer of the sky in the period prior to the invention of the telescope. His original name, Thyge Ottesen Brahe, in modern Danish is pronounced [шtsy mark ◆ diary.ا. εb.に].

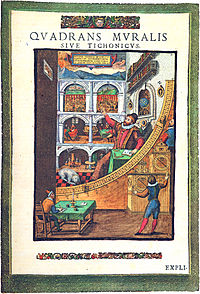

He had Uraniborg built, a palace that would become the first institute for astronomical research. The instruments designed by Brahe allowed him to measure the positions of the stars and planets with a precision far superior to that of the time. Lured by Brahe's fame, Johannes Kepler accepted an invitation from him to work with him in Prague. Tycho believed that progress in astronomy could not be achieved by occasional observation and spot investigations but needed systematic measurements, night after night, using the most precise instruments possible.

After Brahe's death, the measurements of the position of the planets passed into the possession of Kepler, and the measurements of the movement of Mars, particularly its retrograde motion, were essential for the latter to be able to formulate the three laws that govern the movement of the planets.

Biography

Childhood and youth (1546–1566)

Tycho Brahe was born on December 14, 1546 in Knudstrup, Scania, then belonging to Denmark and later to Sweden. He was the eldest son of a Danish noble family: Otte Brahe, Tycho's father, was a privy councilor to the king and ended his career as Governor of Helsingborg Castle. Beate Bille, Tycho's mother, also came from an important family that had produced important churchmen and politicians. Christened Tyge he later Latinized his name to the form by which he is commonly known, Tycho.

Young Tycho was raised by Joergen Brahe, an uncle of his who had no children of his own, who took him to his residence in Tostrup when he was just over a year old. Joergen's intention was that Tycho should follow, like himself, a career in the service of the king, so he provided him with a solid humanistic training in Latin and in 1559, at the age of thirteen, sent him to the University of Copenhagen. It was during his stay there that, on August 21, 1560, an eclipse of the sun occurred, an event the previous prediction of which made an enormous impression on the young Tycho. From then on, and with the apparent indulgence of his uncle, he spent his time in Copenhagen studying mathematics and astronomy. We know, for example, that he purchased and painstakingly annotated a Latin edition of Ptolemy's works.

Later, in 1562, he left Denmark to complete his education and went to the University of Leipzig with the intention of studying law, although most of his time was devoted to his first astronomical observations. During his stay there, as a result of a conjunction between Jupiter and Saturn that occurred on August 24, 1563, it was when he realized the errors that astronomical forecasts made: up to a month, and even in the most recent tables. you need several days.

Tycho Brahe left Leipzig in May 1565 and returned to Copenhagen at the suggestion of his uncle Joergen, who saw fit because of the complications of the war between Sweden and Denmark in some of whose naval battles he himself took part in. Almost immediately, on June 21, Joergen died due to health complications caused by helping King Frederick II when he fell into the water from a bridge in Copenhagen Castle. Despite the fact that Tycho Brahe's family was opposed to his interest in astronomy, he had received the inheritance from his uncle and was able to continue his training on his own. In 1566 he undertook a journey, first visiting the University of Wittenberg and later settling in Rostock, from which university he would graduate, undertaking studies including astrology, alchemy, and medicine.

At the end of 1566, on December 29, a dispute with another Danish aristocrat (according to one of the versions caused by the latter's mocking of an astrological prediction by Tycho about the death of Suleiman the Magnificent when the sultan was already deceased) culminated in a duel in which a blow took off the top of Tycho's nose. From then on, to hide his wound, he always had to use a prosthesis specially made of gold and silver.

The beginnings of his career (1567–1576)

At this time Tycho Brahe was already achieving some renown as a scholar and on May 14, 1568 King Frederick offered him the first vacant post of canon in Roskilde Cathedral, since at that time it carried no religious obligations and was dedicated to scholars by royal appointment.

Tycho continued his travels, visiting Wittenberg again and, after a season in Basel, he settled in Augsburg at the beginning of 1569 where he continued his astronomical observations with the help of a gigantic dial with a radius of 6 meters that he had built. However, he had to return to Denmark in 1570 because of the serious illness of his father, Otto, who would finally die in May 1571.

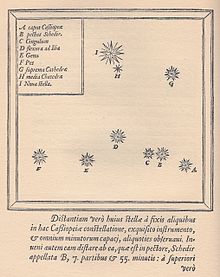

Tycho settled with his maternal uncle Steen and turned his attention to chemistry until in 1572 when he observed a strange event in Cassiopeia: a new star had appeared and was visible for eighteen months. His observations on the star, today known as the supernova SN 1572 or Nova Tycho, were summarized in a book entitled De nova stella, in which he appears for the first time in the astronomical vocabulary the word nova.

The following year Tycho began to live with Cristina (or Kirstine), a girl from the Knudstrup area with whom he never formally married, probably because of the difference in social position. In any case, the couple's coexistence was a success and they had eight children, of whom four girls and two boys survived infancy and were recognized after their death as legitimate descendants.

In 1574 Tycho Brahe gave classes and made his astronomical observations in Copenhagen, although somewhat dissatisfied with the conditions of his work, he considered settling in Basel. Given this, and in view of his growing prestige, to retain him the king first offered him to settle in a royal castle and then, in view of his refusal, agreed to give him the small island of Hven, with the addition of the construction of a house and the granting of an income. The transfer document was signed on May 23, 1576 and, in addition to the house, Tycho also built what would later be known as the Uraniborg Observatory, named after Urania, the muse of astronomy.

The years of observations on the island of Hven (1576–1597)

On the island of Hven, Tycho Brahe was able to count on everything he needed for his work: he built a second observatory in addition to Uraniborg, which, in addition to having galleries for observation, offices for himself and his assistants, and a library, was equipped with The best instrumental of the time. He also set up a printing press and even a paper mill to ensure the publication of his works.

Tycho Brahe's main task in the two decades he spent working at Uraniborg was the routine, albeit extremely important, task of measuring the positions of the planets relative to the fixed stars. His data were considered the highest quality in Europe and so, when he spotted a comet on November 13, 1577, it was his calculations that were considered the definitive demonstration that its orbit ran between the planets and not between the Earth and the Moon..

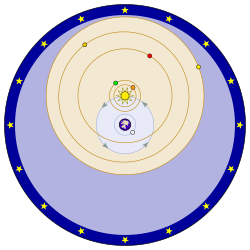

Based on his observations, he published in two volumes between 1587 and 1588 the book Astronomiae instauratae progymnasmata (Introduction to the new astronomy) where he exposed a model of the intermediate universe between that of Ptolemy and Copernicus, in which although the Earth is considered fixed and the Sun revolves around it, the Sun was the center of the orbits of the other planets.

Tycho Brahe's position in Denmark began to weaken in 1588 when King Frederick II died and the succession fell to his son Christian IV. As Tycho was only eleven years old, responsibility for governance fell to a council of nobles who in principle continued to honor the previous terms of the royal agreement with Tycho. Tycho was already a celebrity and received such distinguished visitors as King James VI of Scotland, who had traveled to Denmark on the occasion of his marriage to Princess Anne, the king's sister. The astronomical tables that Tycho was compiling needed completion. massive mathematical operations and, probably as a result of this visit, James VI's doctor, John Craig, communicated to John Napier a technique used in Denmark with a trigonometric basis to reduce products to sums, prostapheresis, closely related to the logarithms, whose theory Napier was founding at the time. Although his work continued, and he compiled a catalog of about a thousand fixed stars in 1595, he was piling up problems with his holdings in the area and becoming less and less comfortable with it. with your position. Thus, the situation worsened even more when in 1596 Cristián IV was crowned and took saving measures such as withdrawing Tycho's continental properties and reducing the budget assigned to the observatory. Although he was still wealthy, in April 1597 Tycho Brahe decided to leave Hven, taking his assistants, transportable instruments and even the printing press with him. After a season in Copenhagen he temporarily settled in Rostock.

Final years, stay in Prague and association with Kepler (1597–1601)

From Rostock Tycho Brahe continued to correspond with King Cristián IV, but they were unable to settle their differences and the final break took place. He then traveled to Wandsbeck, near Hamburg, and as he continued to search for a suitable place to continue his work, he received an offer from Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II of Habsburg. Rudolf was the only Habsburg to establish permanent residence. in Prague, the capital of Bohemia, which he turned into one of the main artistic and cultural centers of Europe. Despite his political and military failures, Rudolf II is remembered as a great protector of the arts and sciences. He was particularly interested in astrology and also encouraged purely astronomical research. Installed in the Prague Castle, the Hradcany, he built in a small Renaissance palace belonging to the complex, the Belvedere, an observatory where he spent hours and hours following the course of the stars.

Tycho Brahe arrived in Prague in June 1599 and was received in audience by the emperor himself, who granted him the title of imperial mathematician, a considerable income, and gave him a choice of three castles to install his observatory, of which Tycho chose the one located in the town of Benatky, 35 kilometers from Prague. He summoned his family, who had temporarily stayed in Dresden, and then commissioned his eldest son to bring the large astronomical instruments that had remained there from Hven. Although Tycho was in his fifties and would make no more major discoveries, by this time he was already in correspondence with the figure who could ultimately best harness his enormous wealth of data, Johannes Kepler.

Kepler was a professor of mathematics in the Austrian city of Graz, earning additional income from astrology. He was also a staunch Protestant and had to leave Styria when the devout Catholic Archduke Ferdinand seized control of the region and wanted to remove the influence of the Reformation from it. Thanks to the mediation of a Styrian nobleman, Baron Hoffman, also an adviser to Rudolf II, Kepler and Brahe met for the first time on February 4, 1600. From the beginning relations between the two were tense: Kepler was aware of his ability, needed a paid position, and made demands that Tycho Brahe found excessive, while failing to give him full access to his precious data. Things finally settled to the point that Tycho offered to pay Kepler for the transfer from Graz and mediated with the emperor, who granted him a residence to which the Kepler family moved in February 1601. Finally, he was received by the emperor, who offered him a position as Brahe's assistant with the specific task of compiling new tables of stellar positions, which would later be known as Rudolphine Tables.

Death of Tycho Brahe (1601)

This always tense collaboration did not last long as on October 13 Tycho Brahe fell seriously ill. According to Kepler's own version, and in order not to commit a breach of etiquette, Tycho had refused to leave the table to attend to his needs during a banquet in Prague, which could be the cause of serious complications due to uremia according to modern medical diagnosis. He was delirious for several days during which he was heard lamenting with anguish that his life had not passed in vain ("Ne frustra vixisse videar "), but he finally regained consciousness. lucidity on the morning of October 24. On his deathbed, he entrusted Kepler with the task of completing the Rudolphine Tables and gave him responsibility for all his astronomical data with the express request that he demonstrate on their basis the validity of his model of the universe against that of Copernicus. In the following years Kepler had continual problems with Tycho's heirs, who wanted to see this commitment fulfilled and were eager to see his publications in print, probably also for monetary reasons.

Tycho Brahe died on October 24, 1601. He was buried, surrounded by great ceremony, on November 4 in the Church of Our Lady before Tyn in Prague, where his tomb still stands.

In 1999 the tomb of Tycho Brahe in Prague was opened to analyze his hair: such high doses of mercury were found that mercury poisoning is now considered a possible alternative cause of death. Since Brahe was interested in alchemy and medicine, and since mercury was a common element in the alchemical medicines prepared by Tycho himself, it is likely that he died of poisoning from his own medicines while trying to recover from his urinary problems. Scientists are currently studying the mortal remains for evidence of mercury poisoning.

Scientific trajectory

Tycho Brahe was the last of the great observing astronomers of the pre-telescope era. On August 24, 1563, while he was studying in Leipzig, a conjunction of Jupiter and Saturn occurred, an event predicted by existing astronomical tables. However, Tycho realized that all the predictions about the date of the conjunction were wrong by days or even months. This fact had a great influence on him. Brahe realized the need to compile new and precise planetary observations that would allow him to make more accurate tables.

During his scientific career he zealously pursued this goal. Thus he developed new astronomical instruments. With them he was able to carry out a precise stellar catalog of more than 1000 stars whose positions he measured with a much higher precision than had been achieved until then (777 of them with a very high precision). Tycho's best measurements were accurate to within half a minute of arc. These measurements allowed him to show that comets were not meteorological phenomena but objects beyond Earth. Since then his scientific instruments have been widely copied in Europe.

Tycho was the first astronomer to perceive the refraction of light, draw up a complete table, and correct his astronomical measurements of this effect.

The complete set of observations of the trajectories of the planets was inherited by Johannes Kepler, Brahe's assistant at the time. Thanks to these detailed observations, Kepler would be able, a few years later, to find what are now called Kepler's laws that govern planetary motion.

Tycho's Star

In 1572, when he was 26 years old, Tycho observed a supernova in the constellation Cassiopeia. At that time, it was believed in the immutability of the sky and in the impossibility of the appearance of new stars, but its brilliance was indisputable.

Initially the star was as bright as Jupiter but soon exceeded magnitude -4, being visible even by day. It gradually faded out of sight by March 1574. When Tycho published detailed observations of this supernova appearance he instantly became a respected astronomer. He called the star Stella Nova (& # 39; New Star & # 39; in Latin).

Tycho was not the first to discover the appearance of this supernova, but he published the best observations of its appearance and the evolution of its brightness, which is why it is known by its name.

Heliocentrism

The system of the Universe that Tycho presents is a transition between the geocentric theory of Ptolemy and the heliocentric theory of Copernicus. In Tycho's theory, the Sun and the Moon revolve around the stationary Earth, while Mars, Mercury, Venus, Jupiter and Saturn would revolve around the Sun.

Brahe was convinced that the Earth remained static in relation to the Universe because, if it were not, the apparent motions of the stars should be visible. However, although such an effect does exist and is called parallax, the reason he did not prove it is that it cannot be detected with direct visual observations. The stars are much further away than was thought reasonable at the time.

Tycho Brahe's theory is partially correct. Usually the earth is considered revolving around the sun because the latter is taken as a point of reference. But if the earth is considered as a reference, the sun revolves around the earth, as well as the moon. However, Brahe thought that their orbit was circular, when in reality they are ellipses. The shape of the orbits was proposed by Kepler in his first law, based on the observations of Tycho Brahe.

In subsequent years, Galileo's observations of the phases of Venus in 1610 tipped scientists toward the heliocentric theory.

Uraniborg and other observatories

King Frederick II of Denmark and Norway was so impressed with Brahe's observations in 1572 that he financed the construction of two observatories for him on the island of Hven in the Sund Strait. The observatories were called Uraniborg and Stjerneborg, 'Urania Castle' and 'Castillo de las Estrellas'. The former also had a laboratory for Tycho Brahe's alchemical experiments.

On the king's death, Tycho quarreled with his successor, Christian IV, and went to Prague in 1599. There he won the favor of Emperor Rudolf II, who names him an "imperial mathematician," offers him a mansion, and lets him Choose between several castles to build a new observatory. Tycho Brahe chooses the castle of Benátky nad Jizerou, 50 km from Prague. Since Rudolf II was passionate about astrology, Brahe had to provide astral charts for the high members of the court, as well as elaborate astrological interpretations of events, such as the arrival of the comet of 1577 and the appearance of the supernova of 1572.

The works and installation of his instruments become more complicated and Brahe decides to return to Prague. In Prague, Brahe finally met Kepler, to whom he would entrust the results of his measurements of the movements of the Moon and the planets carried out over decades, data that would allow Kepler to publish the Rudolphine Tables in 1627.

Brahe and astrology

It has been said that Brahe, like many astronomers of the time, seems to have accepted astrology in two of his early works, now lost, believing that the movement of the planets influenced terrestrial events. Tycho also worked on weather forecasting, made astrological interpretations of the supernova of 1572 and the comet of 1577, and wrote astrological charts for his patrons, Frederick II and Rudolf II. In the natural philosophy of Tycho Brahe, astrology and alchemy were fundamental parts.

However, according to historian of science and scientist David Brewster, Brahe published a treatise on principles of astrology in which he rejected the practice as quackery. According to this account, Brahe expressed skepticism about the multiplicity of astrological systems. and he preferred an astronomical work based on mathematics.

Places named in his honor

- In 1935 the UAI decided in its honor to call "Tycho" a lunar astroblem.

- Mars Tycho Brahe's crater.

- The Nova de Tycho (SN 1572), a supernova.

- The asteroid (1677) Tycho Brahe.

- The planetarium of the city of Copenhagen.

Contenido relacionado

Herod I the Great

Dec. 24

Gules