Twelve-tone

The vast majority of Western music is composed on a structure called the tonal system that regulates the relationships between the notes of a scale and the chords that emerge from it. The system is organized around a note that will be called tonic and will give its name to the tonality, which may be major or minor (C Major or E minor for example). Dodecaphonism proposes in its rules the equality of all the notes included in an octave, eliminating the tonic as the most important note around which the rest of the sounds are ordered.

Historically, it comes directly from «free atonalism», and arises from the need at the beginning of the 20th century to coherently organize the new possibilities of music and focus it on emerging sensibilities. As a fundamental rule no sound is repeated until all other tones have been sounded.

Twelve-tone serialism

Main link: serialism.

The proposal of dodecaphonism is to establish a serial principle to the twelve notes of the chromatic scale. The chromatic scale is one that includes all the semitones between a note and its octave (for example, if we start in C, the chromatic scale would be the following sequence: C, C sharp, D, D sharp, E, F, F sharp, sol, sol sharp, la, la sharp, si ―or, for the sharps, their corresponding flat notes―). The composer chooses a particular order in which these notes should be played, with one not being able to be repeated until the other eleven have been played (thus preventing any tonal coherence). This sequence is called the “original series” (O).

In this compositional technique, the twelve notes of the chromatic scale have the same hierarchical equality, since one cannot be repeated without the other eleven having been previously played. There is no longer, as tradition had established, a fundamental note (tonic) from which the others take a particular hierarchy. There are no longer dominants, subdominants, sensitive. Now, the only governing structure will be the one that the composer has determined in the original series, from which the development of the work will take place.

Original Series

Once the order in which the twelve notes must be played has been established, that is, the previously named “original series” (O), the original series is transmuted to its retrograde (R), that is, the notes of the original series played in the reverse order (the last note in the series is played first, the next to last second, the third last third, etc.). Subsequently, the original series is put in its inversion (I), that is, inverting the direction of the intervals between the twelve notes. If between the first note and the second of the original series there is an interval of, for example, two tones in an ascending direction, now between the first and the second note there must be two tones in a descending direction (for example, do-mi in the original series, and C-flat in inversion). Finally, the retrograde of the inversion (RI) is established, that is, the inversion (I) played in the opposite order. Morhead and MacNeil provide a clear example (see Example 1).

Additionally, each of these four possibilities (O, R, I, RI) can be transposed to any interval, so up to 48 transpositions of the series can be played (the twelve degrees of the chromatic scale multiplied by the four possibilities O, R, I and RI). Naturally, the composer can choose how many mods to include, without all 48 being forced.

Symmetric series

- Threesome

In other works you can find symmetrical series which implies a "mirror" among its 12 notes. An example of this kind of series can be found in Anton Webern's Symphony Op. 21:

This type of series emanates only 24 series, half the possibilities of a normal series. If a matrix table is made, it will be seen, for example, that the original series 1 is equal to the retrograde of the original of note 12, that the original series 11 is equal to the retrograde of the original 2, etc., and that the inversion series 1 is equal to the retrograde series of inversion 12, that the inversion 2 series is equal to the retrograde series of inversion 11, and so on.

- In relation to the same intervallic in reverse direction

Another type of symmetrical series is also used by Webern in his String Quartet Op. 28:

In this series we have the same intervallic starting between notes 6 and 7, with the descending minor third as the common interval between the two starting points and heading in the opposite direction to the beginning and end. Mirror tritone relationships are not given as in the series of Webern's Op. to the retrograde series of inversion 12, the original 4 equal to the retrograde series of inversion 11, and so on.

It also happens that there are pan-interval series (those that have all the possible intervals within an octave) and symmetric pan-interval series.

Twelve-tone in works

Schönberg introduced dodecaphonism in his Fünf Klavierstücke , op. 23 (further developed in his Serenata, op. 24; his Suite for piano, op. 25; his Variations for Orchestra, op. 31; his Klavierstück , op. 33a). This technique was adopted -although with different modifications and contributions- by his disciples Alban Berg and Anton Webern. However, Berg (Der Wein; Violin Concerto; Lyrical Suite for string quartet; his opera Lulu) sought to preserve some tonal links within the twelve-tone structure, and never, in any of his works, strictly adhered to a particular series. Webern (Concerto, op. 24; String Quartet, Op. 28), on the other hand, he is much more radical with the twelve-tone method, since all the formal elements of some of his works derive entirely from it and not from any previous musical convention or other influences.

Some serialist composers have resorted to this method using fewer than twelve notes of the chromatic scale. Even Schönberg came to use series with fewer than twelve notes (in the second of his Fünf Klavierstücke, op. 23 and his Serenade, op. 24), as did Stravinsky. in his Cantata and in In memoriam Dylan Thomas, where he adopts serialism despite being considered by many as antagonistic to Schönberg. Also some composers, notably Olivier Messiaen (in his Quatour pour la fin du temps) and Luciano Berio (Nones), created series with more than twelve notes, naturally repeating some.

History of the use of the technique

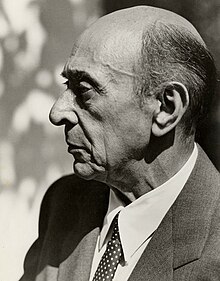

Founded by the Austrian composer Arnold Schönberg in 1921 and described privately to his associates in 1923, the method was used for around 20 years by the Second Viennese School, consisting of Alban Berg, Anton Webern, Hanns Eisler and Arnold himself. schoenberg. Rudolph Reti, one of the initiators, said that "replacing one structural force (tonality) by another (increasing thematic units) is itself the fundamental idea of twelve-tone music", arguing its emergence from Schönberg's frustrations with free atonality. The technique was widely used in the 1950s, taken up by composers such as Luciano Berio, Pierre Boulez, Luigi Dallapiccola, Juan Carlos Paz, and, after Schönberg's death, Igor Stravinsky. Some of these composers extended the technique to be able to control other aspects and not only the height of the notes, such as duration, articulation, etc., thus producing serial music. Some included all the elements of the music in the serial process, which is known as Serialism|integral serialism. On this page reference is made to the prohibition of the repeated use of a note, but rather the repetition of the melodic sequence (intervals), even has to be restricted and this is the "interval pattern".

Contenido relacionado

Tata Nacho

Charles Jesse

Satt 3