Troy

Troy or Ilion (in Greek Τροία —Troia—, Ίλιον —Ilion—, or Ίλιος — Ilios) is an ancient Anatolian city located on the site today known as Hisarlik Hill in Turkey (Turkish for '[hill] endowed with fortress'). In studies by Frank Starke (1997), J. David Hawkins (1998) and W. D. Niemeier (1999), the word Wilusa was the name used in Hittite for the city of Troy.

The mythical Trojan War took place there. This famous war was described, in part, in the Iliad, an epic poem from Ancient Greece attributed to Homer, who would compose it, according to most critics, in the VIII a. C. Homer also makes reference to Troy in the Odyssey. The legend was completed by other Greek and Roman authors, such as Virgil in the Aeneid.

Historical Troy was inhabited from the early 3rd millennium BCE. C. It is located in the current Turkish province of Çanakkale, next to the Dardanelles Strait, between the Escamandro (or Xantho) and Simois rivers and occupies a strategic position in the access to the Black Sea. In its surroundings is the Ida mountain range and in front of its coasts the nearby island of Tenedos can be seen. The special conditions of the Dardanelles Strait, in which there is a constant current from the Sea of Marmara to the Aegean Sea and where a north-easterly wind usually blows during the season from May to October, suggests that the ships that in ancient times Those who intended to cross the strait often had to wait for more favorable conditions during long periods in the port of Troy.

After centuries of oblivion, the ruins of Troy were discovered in excavations carried out in 1871 by Heinrich Schliemann, after initial surveys carried out from 1865 by Frank Calvert. In 1998, the archaeological site of Troy was declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO, stating that:

It is of immense importance for the understanding of the evolution of European civilization in a basic state of its early stages. It is also of exceptional cultural importance because of the profound influence of Iliad Homer in the creative arts for more than two millennia.

Legendary Trojan

Foundation

According to Greek mythology, the Trojan royal family was started by the Pleiad of Electra and Zeus, parents of Dardanus. He crossed over to Asia Minor from the island of Samothrace, where he met Teucer, who treated him with respect. Dardanus married Batiea, daughter of Teucer, and founded Dardania. After the death of Dárdano, the kingdom passed to his grandson Tros. Zeus kidnapped one of his sons, named Ganymede, because of his great beauty, to make him a cupbearer to the gods. Ilo, another son of Tros, founded the city of Ilium and asked Zeus for a sign. Coincidentally, he found a statue known as Palladium, which had fallen from the sky. An oracle said that as long as the Palladium remained in the city, it would be impregnable. Then Ilo built the temple of Athena in his city, in the same place where he had fallen.

The inhabitants of Troy are called Teucros, while Troy and Ilion are the two names by which the city was known; therefore Teucer, Tros and Ilo were considered its eponymous founders. The Romans related the name of Ilion to that of Iulo (in Latin Iulus), son of Aeneas and mythical ancestor of the gens Iulia or Iulii, to which Julius Caesar belonged.

Heracles' expedition against Troy

The gods Poseidon and Apollo built the walls and fortifications around Troy for Laomedon, son of Ilo. When Laomedon refused to pay them their agreed wages, Poseidon flooded the land and sent a sea monster that wreaked havoc on the area. As a condition for the evils on the city to cease, an oracle demanded the sacrifice of Hesione, the king's daughter, to be devoured by the monster, so she was chained to a rock on the coast. Heracles, who had arrived at Troy, broke Hesione's chains and made a pact with Laomedon: in exchange for the divine mares that Zeus had given to Tros, Laomedon's grandfather, in compensation for the kidnapping of Ganymede, Heracles would free the city from the monster. The Trojans and Athena they built a wall that was to serve as a refuge for Heracles. When the monster reached the defensive work, it opened its enormous jaws, and Heracles threw himself armed into the jaws of the monster. After three days in his womb wreaking havoc, he emerged victorious and completely bald.

In other versions, the confrontation with the monster took place within the outbound path of the Argonauts expedition, and the way in which Heracles killed the monster was by throwing a rock at its neck.

But Laomedon did not fulfill his part of the pact, since he replaced two of the immortal mares with two ordinary mares and, in retaliation, Heracles, in anger, threatened to attack Troy and sailed back to Greece. After a few years, Laomedon He led a punitive expedition of eighteen ships, after recruiting in Tiryns an army of volunteers among which were Iolaus, Telamon, Peleus, the Argive Ecles, son of Antiphates, and Deimachus, the Boeotian. Telamon had an outstanding performance in the siege of the city by breaching the walls of Troy and entering first. Captured Troy, Heracles killed Laomedon and his children, except for the young Podarces.

Hesione was given to Telamon as a reward and was allowed to take any one of the prisoners. She chose hers her brother Podarces hers and Heracles arranged that before her he should become a slave and then be rescued by her. Hesione removed the golden veil from her head and gave it as a ransom. This earned Podarces the name Priam, meaning "rescued". After having burned the city and laid waste to the surrounding area, Heracles departed from the Troads with Glaucia, daughter of the river-god Scamander, leaving Priam as King of Troy, by virtue of his sense of justice, since he was the only one of Laomedon's sons who opposed his father and advised him to give the mares to Heracles.

Trojan War

During the reign of Priam, and because of the kidnapping of Helen of Sparta by the Trojan prince Paris, the Mycenaean Greeks, commanded by Agamemnon, took Troy after having laid siege to the city for ten years. Eratosthenes dated the Trojan War between 1194 and 1184 BC. C., the Marmor Parium between 1218/7 and 1209/8 BC. C., and Herodotus in 1250 B.C. c.

Most of the Trojan heroes and their allies died in the war, but two groups of Trojans, led one by Aeneas and the other by Antenor, managed to survive and sailed first to Carthage and then to the Italian peninsula., where they became the ancestors of the founders of Rome, while the latter arrived on the northern coast of the Adriatic Sea and the founding of Padua was also attributed to them. The first settlements of these survivors in Sicily and Italy were also given the name of Troy. The Trojan ships in which they traveled were transformed by Cybele into naiads, when they were to be burned by Turnus, Aeneas's rival in Italy.. According to Thucydides and Hellanicus of Lesbos, other surviving Trojans settled in Sicily, in the cities of Erice and Aegesta, receiving the name of Élimos. In addition, Herodotus comments that the Maxies were a tribe from western Libya whose members claimed being descendants of men who came from Troy. Some of these mythical stories, sometimes contradicting each other, appear in the Iliad and the Odyssey, the famous Homeric poems, and in other later works and fragments.

Historicity of the Trojan War

The problem of the historical authenticity of the Trojan War has given rise to conjectures of all kinds. The archaeologist Heinrich Schliemann admitted that Homer was an epic poet and not a historian, and that he could exaggerate the conflict for the sake of poetic freedom, but not that he invented it. Shortly after, the also archaeologist Wilhelm Dörpfeld defended that Troy VI was a victim of Mycenaean expansionism. This idea was joined by Sperling in 1991. Studies by Blegen and his team admitted that an Achaean expedition must have been the cause of the destruction of Troy VII-A around 1250 BC. C. —Currently the end of this city is usually set closer to 1200 B.C. C.—, however until now it has not been possible to demonstrate who the attackers of Troy VII-A were. Hiller, on the other hand, also in 1991, pointed out that there must have been two wars in Troy that marked the end of Troy VI and Troy VII-A. Meanwhile, Demetriou, in 1996, insisted on the date of 1250 B.C. C. for a historical Trojan war, in a study in which he based himself on Cypriot deposits.

Against them is a current of skeptical opinion headed by Moses Finley, who denies the presence of Mycenaean elements in the Homeric poems and points out the absence of archaeological evidence about the historicity of the myth. Other prominent scholars belonging to this skeptical current are the historian Frank Kolb and the archaeologist Dieter Hertel. Joachim Latacz, in a study in which he relates archaeological sources, Hittite historical sources and Homeric passages such as the Catalogue of the ships of book II of the Iliad, considers the origin proven. Mycenaean origin of the legend but, regarding the historicity of the war, he has been cautious, only conceding that a historical substratum is likely.

An attempt has also been made to substantiate the historicity of the legend with the study of contemporary historical texts from the Late Bronze Age. Carlos Moreu has interpreted an Egyptian inscription from Medinet Habu, in which the attack on Egypt by the sea peoples is narrated, in a different way from the traditional interpretation. According to this interpretation, the Achaeans would have attacked various regions of Anatolia, including Troy and Cyprus, and the attacked peoples would have established a camp in Amurru and later would have formed the coalition that faced Ramses III in the eighth year of his reign..

Historical Trojan

Trojan in Hittite sources

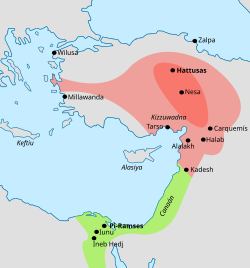

The city of Troy was inhabited from the first half of the 3rd millennium BC. C., but its moment of greatest splendor coincided with the rise of the Hittite Empire. In 1924, shortly after the decipherment of the Hittite script, Paul Kretschmer had compared a place name appearing in Hittite sources, Wilusa, with the Greek place name Ilios, used as the name of Troy. Scholars, based on linguistic evidence, established that the name Ilios had lost an initial digamma and had previously been Wilios. Added to this was another comparison between a Trojan king who appears written in Hittite documents, named Alaksandu, and Alexander, used in the Iliad as Alternative name for Paris, Trojan prince.

These proposals to identify Wilusa with Wilios and Alaksandu with Alejandro were initially controversial: the geographical location of Wilusa was doubtful and in Hittite sources the name of Kukunni also appears as king of Wilusa and father of Alaksandu, without apparent relationship with the legend of Alexander, although some have pointed out that this name could have its equivalent in Greek in the name Κύκνος (Cycno), another character from the Trojan cycle. However, in 1996, Frank Starke proved that, indeed, the location of Wilusa must be located in the same place where the Troad region is. However, some archaeologists such as Dieter Hertel still refuse to accept this identification between Wilusa and Ilios. The main Hittite documents that mention Wilusa are:

- The call Alaksandu Treatywhich was a covenant between the Hittite King Muwatalli II and Alaksandu, King of Wilusa, dating back to the beginning of the centuryXIIIa. C. The text of this treaty has been deduced that Wilusa had a subordination relationship with respect to the Hittite Empire.

Among the gods named in the treaty as witnesses to the pact are Apaliunas, which some researchers have identified with Apollo, and Kaskalkur, whose meaning is 'path to the underworld'. Regarding Kaskalkur, the archaeologist Korfmann indicates that:

In this way, the water courses that disappeared on the soil of the water regions were designated and resurfaced outside, but the Hittites also used this concept for artificially installed water galleries.

This divinity has therefore been associated with the discovery of a cave with a spring 200 meters south of the acropolis wall which, after analyzing the limestone of the walls, has been determined to already exist at the beginning of the third millennium to. C. and around which myths could have arisen. The coincidence of the allusion by the author Esteban de Byzantio to the fact that a certain Motylos, who could be a Hellenization of the name Muwatalli, provided hospitality to Alexander and Helena, has also been pointed out.

- A letter written by the king of the country of the Seha River (the milestone vassal state) Manapa-Tarhunta to King Muwatalli II, and therefore also dated around 1295 B.C., where information is given from a certain Piyamaradu who had led a military expedition against Wilusa and against the island Lazba, identified by the researchers with Lesbos.

- In the Tawagalawa Charter (h. 1250 B.C.), generally attributed to Hattusili III, the Hittite king refers to ancient hostilities between the Hittites and the ahhiyawa possibly over Wilusa, amicably resolved in this letter: "Now is when we have reached an agreement on Wilusa's affair with which we were enmity."

The last mention of Wilusa preserved in Hittite sources appears in a fragment of the so-called Millawanda Letter, sent by King Tudhaliya IV (1240-1215 BC) to an unknown addressee. In it, the king of the Hittites explains that he will use all means at his disposal to restore Walmu, a successor to Alaksandu who had been dethroned and exiled, to the throne of Wilusa. However, T. R. Bryce says that this fact is mentioned earlier, noting it in his reinterpretation of the Tawagalawa Charter. Also, in the annals of King Tudhaliya I/II (XIV BC), he declares that after a conquest expedition, a series of countries declared war on him, in whose list are, followed by: «...Wilusiya country, Taruisa country...». Some researchers, such as John Garstang and Oliver Gurney, have deduced that Taruisa could be identified with Troy; however, this equivalence is not yet supported by the majority of Hititologists.

Trojan in Egyptian sources

The mention of Troy in Bronze Age Egyptian sources is not certain. However, some scholars have investigated the relationship it could have with the Medinet Habu inscriptions that tell of the battle of the Egyptians at the time of Ramesses III against the sea peoples, who attempted an invasion of their territory around 1176 BC. C. According to inscriptions, the Egyptians defeated a coalition of peoples of dubious identification in a land battle and in a sea battle. Among the denominations of the peoples that made up the coalition are the Weshesh —who could be related to Wilusa— and the Tjeker —who have been related to the Trojans.

In more recent Egyptian sources, it is interesting the testimony collected in the list of pharaohs by Manetho, an Egyptian priest of the III century a. C., which indicates that the fall of Troy took place during Twosret's rule, which would place it between the years 1188 and 1186 BC. C.

Troy in Greek historical sources

The first Greek settlers to arrive in the territory of the Troad must have been Aeolian emigrants. The origin of the city's sanctuary of Athena could date back to 900 BC. C. The archaeologist Dieter Hertel explains that:

As very late from 900 B.C. was also venerated the Greek goddess Athena, as deducted from the thick sediment on the lining of the north-eastern bastion well, which was completely filled with offering residues.

Other authors, on the other hand, maintain that the Greeks did not come to colonize Troy until the year 700 BC. C. In any case, until the 3rd century B.C. C. must have been a small population entity, lower level than other nearby coastal colonies such as Sigeo and Aquileo. Troy was part of the kingdom of Lydia, with the city of Sardis as its capital probably since the time of Aliates, one of the Kings of the Mermnada dynasty, early 6th century BCE. C. The last king of this dynasty was Croesus, who came to reign over almost all the territories west of the Halis river.

The Persians, under Cyrus II the Great, defeated Croesus at the Battle of the Halis River and invaded his realm, including Troy, in 546 BC. C. Between 499 B.C. C. and 496 a. C., during the Ionian revolt, the Aeolians supported the Ionians against the Persians under Darius I, but the rebellion was put down. Himeas was the Persian general who subdued Ilium in this revolt. Later, Xerxes I's visit to Troy in 480 BC. C. was also related by Herodotus, who tells that he sacrificed a thousand oxen to Athena and the magicians offered libations to the heroes. One of the consequences of the signing of the Peace of Callias between the Persians and the Athenians was that Troy, along with many territories of Asia Minor, was under the direction of Athens from 449 B.C. c.; then, at the end of that same century, it came to belong to a Dardan principality dependent on Persia; but soon after, from 399 B.C. C., became an ally of Sparta until in 387 BC. C. returned to control of Persia after the signing of the Peace of Antalcidas with Sparta.

In 360 B.C. C. Charidemus took Ilium, which was reconquered shortly after by Athenodorus of Imbros.

Alexander the Great especially protected the city, which he reached in 334 B.C. C. He considered himself a new Achilles and treasured a copy of the Iliad. The visit of Alexander the Great to Troy is narrated by Arriano, Plutarch and Strabo, among other authors of Antiquity:

He went up to Ilion and made a sacrifice to Athena, as well as libations to the heroes. In the tomb of Achilles, after anointing oil and running naked together with his companions, as usual, he deposited crowns, calling him blessed, for in life he had a loyal friend and after his death a great herald of his glory.

They say that the city of the present ilieos had for a time been a village with a small and humble sanctuary of Athena, but when Alexander came there after the battle of the Gránico adorned the sanctuary with offerings, gave the village the title of city, ordered the commissioners to enhance it with buildings and granted him the freedom and tax exemption.

Arrian, who places the visit of Alexander the Great before the battle of Granicus, also indicates that he paid honors to Achilles while his companion Hephaestion paid them to Patroclus.

According to Strabo's story, after defeating the Persians, Alexander promised to make Ilium a great city, although Lysimachus of Thrace, one of his generals, was the architect of most of the reforms and expansion of the city.

Between the years 275 and 228 B.C. C., Troy belonged to the Seleucid Empire, which years ago had been founded by Seleucus, another of Alexander's successors. From 228 B.C. C. to 197 B.C. C., the city was independent, but with ties to the Kingdom of Pergamum. It returned to belong to the Seleucids between 197 B.C. C. and 190 B.C. C. During all this time the cult of Athena continued to be important. A ritual that was celebrated in his honor was the sacrifice of oxen, which were hung from a pillar or a tree and their throats were opened there.

It was also celebrated, probably from the 8th century century BC. C., a custom related to the myth of the Trojan War: according to legend, Ajax Locrius had dragged princess Cassandra during the sack of Troy while she, to seek divine protection, had clung to the statue of Athena. For this reason, the Locrians had been forced by the Oracle of Delphi to send two or more girls of noble origin to Troy every year for a period of a thousand years. The girls, once they reached the Trojan coast, tried to reach the temple of Athena; if they succeeded, they became priestesses of the temple, but the inhabitants of Troy tried to kill them on their way. If any died, the Locrians had to send another in their place. Most achieved their goal and reached the temple of Athena. There is controversy about when this custom stopped being practiced. Some point out that it ended after the Phocidian War, in 346 BC. c.; others believe it was practiced as late as the 1st century.

Troy in Roman historical sources

The prestige of Troy in Roman times was accompanied by ideological and political motivations linked to the very roots of the founding of Rome. In 190 B.C. C., the Roman troops arrived at the city and after offering sacrifices to Athena they put Ilion under their protection. After the Peace of Apamea, the neighboring cities of Gergita and Retio were united in synecism with Ilium and the city was part of the domains of the Kingdom of Pergamum between 188 B.C. C. and 133 B.C. C., until Pergamum fell under the power of Rome and Troy became part of the Roman province of Asia.

In the year 85 B.C. C., the Roman general Gaius Flavius Fimbria destroyed and sacked Troy during the war against Mithridates, who had fought against Roman domination in the East. Subsequently, Emperor Augustus rebuilt the temple of Athena. Julio César, after the battle of Farsalia, visited, in the year 48 a. C., the city of Ilium, which he considered the homeland of his ancestors. He increased the territory of the city and freed it from tributes. At that same time, the first coin was minted with the image of Aeneas fleeing from Troy with his father Anchises in his arms and the mythical Palladio. According to Suetonius account, Julio César was meditating to transfer his residence to Ilium.

Emperor Caracalla arrived in Ilium in 214 and consecrated a statue of Achilles there and organized military parades around the supposed tomb of the mythical warrior. To make these acts more like the games in honor of Patroclus after his death, narrated in the Iliad , he killed his friend Festus to play the part of Patroclus.

The End of Troy

After the Emperor Constantine promulgated religious freedom through the Edict of Milan and the persecution of Christianity ceased, the Emperor Julian the Apostate, a supporter of the ancient beliefs, visited the city in 354-355, being able to verify that Achilles' tomb was still there and that sacrifices were still offered to Athena. However, in 391 pagan rites were prohibited.

Around the year 500, a great earthquake occurred that caused the definitive collapse of the most emblematic buildings of Troy. It appears that Troy remained a populated settlement during the Byzantine Empire, up to the 13th century, but little is known about it. of events that occurred in it and shortly after the very existence of the city fell into oblivion. After the Fall of Constantinople in 1453, the hill on which Troy stood was called Hisarlik, which in Turkish means 'endowed with strength'.

History of the excavations

The Hisarlik-Bunarbaschi dilemma

Since the early 19th century the finding of inscriptions on coins had convinced Edward Daniel Clarke and John Martin Cripps that On the hill of Hisarlik, about 4.5 km from the entrance of the Dardanelles, in the Turkish province of Çanakkale, the city of Troy was located at least when it was a Greco-Roman city. In his Dissertation on the Topography of the Plain of Troy, published in Edinburgh in 1822, the Scottish scholar Charles MacLaren had hypothesized that the location of the Greco-Roman New Ilium coincided with that of the sung fortress by Homer. To corroborate it, he made a trip to the Troad in 1847 and in 1863 he reissued his work in which he confirmed his hypothesis.

Not all researchers agreed, however. In 1776, the Frenchman Choiseul-Gouffier had opined that ancient Troy was located near the village of Bunarbaschi, about 13 kilometers from the Dardanelles, and this hypothesis was popularized in 1785 by Jean-Baptiste Le Chevalier who, visiting the area, considered that the remains should be on the hill called Balli Dag. So, in 1864, a team led by Austrian diplomat Johann Georg von Hahn excavated that hill and found remains of an ancient Greek colony, but this settlement had only existed between the 7th and 4th centuries BCE. C. and has been identified with the colony of Gentino.

At that time both possibilities were not taken too seriously by most academics.

Heinrich Schliemann

Excavations in the Hisarlik Hill area were first conducted by the engineer John Brunton in 1856, but the exact location of the excavations is unclear. A few years later, in 1865, Frank Calvert undertook excavations in the Hisarlik Hill area. that he found remains of the temple of Athena, of walls and some other ceramic fragments, but had to abandon the works. When the German Heinrich Schliemann happened to visit Calvert during a brief trip he had made to Troad in 1868, he became convinced that the location of Troy was on that hill, and from 1871 the German began excavations there. big scale. The continuation of the works led Schliemann to distinguish seven cities or stages of occupation of the place, assigning the phase of Troy II to Homeric Troy. Among his most striking finds is the so-called Treasure of Priam. From 1882 he returned to excavate at the site together with Wilhelm Dörpfeld, who had worked on the German excavations at Olympia. Schliemann was forced to admit that the Troy II stratum was much older and it was Troy VI that came to be regarded as the Homeric city. After Schliemann's death, Dörpfeld excavated again between 1893 and 1894. The result of these campaigns was the discovery of nine cities built successively one on top of the other.

Later archaeological missions

Between 1932 and 1938, an American team excavated again at the site, under the direction of Carl William Blegen, who differentiated in greater detail each of the construction phases of the cities and proposed Troy VII A as the city destroyed by the Mycenaean Greeks. In 1988 the excavations were resumed, directed by the German Manfred Korfmann, who made important discoveries, such as the discovery of a large slum in Troy VI.

After Korfmann's death in 2005, the excavations were directed by the Austrian Ernst Pernicka. In September 2009, the remains of two people were found along with other ceramic remains that, due to their characteristics, could be from around 1200 BC. C. The results of the excavations were studied in the work unit called Project Troy, at the University of Tübingen, and every year the most important was published in the magazine Studia Troica.

In 2012, the team of archaeologists from the University of Tübingen stopped working in Troy. As of 2013, the excavations became the responsibility of the University of Çanakkale and the director of the excavations, Rüstem Aslan.

Museums with Trojan material

Many of the objects found in the excavations are on display in museums, including the Pushkin Museum in Moscow, the Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg, the British Museum in London, the Museum of Prehistory and Early History in Berlin, and the National Archaeological Museum of Athens.

On the other hand, since 2018 the Trojan Museum has been active next to the archaeological site. It is especially dedicated to all aspects related to settlement and excavations. It exhibits archaeological finds from Troy and its surrounding region transferred from the Çanakkale Archaeological Museum, the Istanbul Archaeological Museum and other places. The Museum of Archeology and Anthropology at the University of Pennsylvania purchased a set of 24 Bronze Age gold jewels in 1966 from a Philadelphia art dealer, but the place of provenance of this collection was unknown, although similarities were noted with other jewels found in Ur, Poliojni (Lemnos) or Troy. In 2009, the archaeologists Ernst Pernicka and Hermann Born examined this collection and, through a scientific analysis of a dust particle attached to one of the objects, determined that its provenance was compatible with that of the Trojan plain. Some years later, the museum reached an agreement with the Turkish Ministry of Culture and Tourism to transfer these works on indefinite loan to Turkey and thus become part of the Trojan Museum exhibition.

The layers of the Trojan settlements

| Chronology of the different levels of the archaeological remains of Troy, according to Manfred Korfmann | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Troy I | 2920-2450 a. C. | ||||||||||||||

| Troy II | 2600-2350 a. C. | ||||||||||||||

| Troy III | 2350-2200 a. C. | ||||||||||||||

| Troy IV | 2200-1900 a. C. | ||||||||||||||

| Troy V | 1900-1700 a. C. | ||||||||||||||

| Troy VI | 1700-1300 a. C. | ||||||||||||||

| Troy VIIa | 1300-1200 a. C. | ||||||||||||||

| Troy VIIb | 1200-950 a. C. | ||||||||||||||

| Troy VIII | 700-85 a. C. | ||||||||||||||

| Troy IX | 85 a. C.-500 d. C. | ||||||||||||||

| Troy X | XIII-XIV centuries | ||||||||||||||

As a result of the different excavations, the history of Troy has been reconstructed and eleven phases of occupation have been established. A first phase, called Troy 0, began around 3500 BC. C. The next four, from Troy I to Troy IV, developed during the 3rd millennium BC. C., having a clear cultural continuity until the V. Troy VI attests to a second flowering of the city. Troy VII is the prime candidate for identification with Homeric Troy. Troy VIII and Troy IX cover Archaic Greece, the Classical period, the Hellenistic and Roman periods. Troy X is the one belonging to the Byzantine period. From the first settlement to Troy VII there are no remains of written documentation that help to assess the historical and social development of the city.

Trojan 0

The remains of a first settlement in Troy originated around 3500 BC. C. These remains were discovered by Manfred Korfmann, but remained to be analyzed, which was later carried out by Rüstem Aslan.

Trojan I

The citadel of Troy I presents ten construction phases developed, according to Carl Blegen and others, over five centuries: between 2920-2500/2450 B.C. C, approx. Its stratigraphic power is more than four meters and it occupies only the northwestern half of the hill. Exposed by Heinrich Schliemann, it consisted of an enclosure of fortified stone walls, 2.50 m thick, probably with quadrangular bastions; traces of the eastern one remain, with a height of 3.50 m and which would control the entrance. It was made up of irregular stones and narrowed at the top. The associated dwellings are rectangular in plan and there are remains of a megaron. Ceramics decorated with schematic human faces appear for the first time. It housed a population whose culture, called Kum Tepe, is considered to belong to the Early Bronze Age. It was destroyed by a fire, rebuilt and thus gave rise to Troy II.

Troy II

Although Troy I was abruptly destroyed, there is no chronological or cultural break with Troy II. The latter developed between 2500/2450-2350/2300 BC. C., in eight construction phases during which it grew to occupy an area of nine thousand m². Its wall, with a polygonal plan, was built with adobe bricks raised on a stone base. It had two gates accessible by stone ramps and square towers at the corners. The largest gates are on the southwest side and gave access to the royal palace, the megaron, through small propylaea. This phase of occupation was discovered by Schliemann and re-examined by Dörpfeld.

The most important building is the megaron, originally 35-40 m and with the largest room measuring about 20 x 10 m, where Dörpfeld found the remains of a platform that may have housed a hearth. The other megara discovered by Dörpfeld must be the private residences of the royal family and the central warehouse with surpluses. According to Dörpfeld, it was a very prosperous city, as evidenced by the remains of the great walled enclosure, the so-called Casa del Rey and its more than 600 wells, where provisions were stored and which generally contained fragments of large conservation jars, probably covered with bricks, scattered throughout the citadel.

The great simplicity of the buildings of the palace complex of Troy II contrasts with the contemporary official architecture of Mesopotamia under the kings of Akkad (2300-2200 BC), with a rich scenic apparatus, such as the residences and the temples of the governors of Lagash, and of the III dynasty of Ur, and the monumental constructions of pharaonic Egypt from the time of the Old Kingdom (2950-2220 BC). This simplicity of the Trojan buildings is surprising when compared to the profusion and richness of the jewelery and goldsmithing of the time, witnessed by the famous treasure that Schliemann attributed to Priam and that Blegen assigned to the Trojan II phase. This is the most enormous and significant artistic heritage of Troy from the third millennium BC. c.

This treasure is made up of valuable objects made of precious metals and stones, which were donated by Schliemann to Germany and after the end of World War II were brought to Moscow, where they are currently located in the Pushkin Museum. Of the nine lots, the most important include collections of daggers, utensils and ornaments for clothing, and many gold and silver tableware. Among the precious objects, a large disc stands out, provided with an omphalos —literally 'navel', a kind of bulge in the center of the object— and a long flattened handle, which ends with a small series of small discs. It was used to sift gold, and it is similar to tools found in Ur and in Babylon, between the end of the third millennium and the beginning of the second millennium BC. C. Among the jewels there are two female diadems that adorned the forehead with a fringe of small and dense gold chains, each one ending with a pendant of gold sheets in the shape of a flower or leaf. They were found along with a series of necklaces and earrings, in a large silver jug.

A fire that occurred around 2300/2250 B.C. C. caused the hasty flight of the inhabitants and marks the end of Troy II.

Troy III-Troy IV-Troy V

Over the course of the third millennium B.C. C., a first wave of invasions by Indo-European peoples marks sensitive changes in the Mediterranean area, also registered in Troy in phases III-V of the life of the city, whose cultural life does not seem to be interrupted, but it does slow down drastically. The remains of the buildings are meager and of inferior quality to those of the preceding ones and the overall image of the site responds more to that of a commercial center than to the prosperous city of the third millennium BC. c.

- Troy III

Over the ruins of Troy II, Troy III (2350/2300 BC-2200 BC) was built, smaller in size but with a carved stone wall. What little is known was also built almost completely made of stone, unlike the previous buildings that were made of adobe. Anthropomorphic vases are characteristic of Troy III, such as the one found by Schliemann in 1872 and which, according to him, represented Athena Ilias.

- Troy IV

With an area of 17,000 m², Troy IV (2200-1900 BC) shows the same walling technique as Troy II and Troy III. On the other hand, the dome ovens and a type of house with four rooms are new.

- Troy V

Troya V (1900 BC-1700 BC) is a complete reconstruction of Troya IV, based on a more regular urban plan and with spacious houses, but without a cultural break with respect to the settlements precedents. With it, the pre-Mycenaean phase of the history of Troy ends.

Troy VI

Troy VI (1700-1300 B.C. or 1250 B.C.) corresponds to the crucial period of Anatolian history between the end of the Assyrian trading colonies of Kültepe-Kanish —around the middle of the 18th century B.C. C.— and the formation and expansion of the Hittite Empire —until the first half of the XIII century B.C. C. -, when a strong earthquake probably finished off the city, which had risen to a new life, after the long preceding phase of "market city".

It was a prosperous place, seat of a king, prince or governor and administrative center that was progressively expanded until it reached the 14th century BC. C. its final form. It was inhabited by immigrants of Indo-European origin who dedicated themselves to new activities such as horse breeding and training, greatly developed bronze technology and practiced the funeral rite of cremation. Most of the pottery fragments are of the so-called "Anatolian gray pottery". The Mycenaean vessels that have also been found are evidence of trade relations between Troy and the Mycenaean civilization.

Among the fundamental structures of Troy VI, the fortress stands out, with the monumental bastion 9 m high and with very sharp angles, in a position similar to that of Troy II, in the Early Bronze Age, dominating the course of the Escamandro. In case of siege, it had a huge cistern 8 m deep inside the central bastion. The layout of the walls, with a diameter of about 200 m —double that of the oldest enclosure—, unfolds into a second concentric fence to the preceding one with an average height of 6 m and a thickness of 5 m. It was reached through a main gate, controlled by a fortified tower and by three other secondary ones, from which wide converging streets started radially towards the northern center of the city, now disappeared. Walking through the gates were rectangular, pillar-shaped stones, each embedded in another block of stone, about the size of a person. This type of architectural elements is quite common in the Hittite sphere. The archaeologist Peter Neve believes that they could be related to the cult of protective divinities of the gates, while Manfred Korfmann suggests that they could be related to the cult of Apollo.

The construction technique is complex, with the stone base structure and the adobe superstructure at a height of 4-5 m. Inside the walls there are still few houses with a rectangular floor plan and a portico, but only the ground floor is preserved: among the most imposing ruins of Troy VI we must point out the so-called "House of the Pillars", trapezoidal in shape, 26 m long and 12 m wide. It consists of a hall, to the east, and a large central room, which ends in three small rooms at the back. It was a public building for royal official ceremonies.

In Troy VI, the layout of the buildings and circulation axes was adapted to the circular shape of the walls, whose center must have been the palace and its temple. On another hill called Yassitepe, closer to the sea, a Bronze Age necropolis has been found with burials of men, women and children, as well as grave goods made of the same types of ceramics found in Troy VI. Some cremation remains have also been found in this place.

The large slum of the city was discovered by Korfmann starting in 1988, aided by a new technique called magnetic prospecting. Following this discovery, the city is attributed an area of 350,000 m², that is, thirteen times larger than the already known acropolis. With also considerable dimensions, Troy surpassed in area that another great city of the time, Ugarit (200,000 m²), and is in fact one of the largest cities of the Bronze Age. Its population would oscillate between 5,000 and 10,000 inhabitants. In the event of a siege, it is estimated that it could house 50,000 inhabitants from the entire region. In front of it, in 1993 and 1995, two parallel trenches 1 to 2 meters deep were discovered, which could have served as a defense against an attack perpetrated with war chariots. In 1995, a gate of the fortification of the aforementioned neighborhood, the start of the wall of the slum and a cobbled road that led from the plain of the Escamandro river to the western gate of the acropolis were also found.

Troy VII

- Troy VII-A

The palace complex of Troy VI was probably destroyed by a violent earthquake around 1300 BC. C., although some researchers are inclined to date its end to around 1250 B.C. c.

Its immediate reconstruction in the successive phase of Troy VII-A has raised the question of which of the two cities was the Homeric Ilium. Carl Blegen rejected Dörpfeld's thesis that it pointed to the Mycenaean fortress of Troy VI—probably destroyed by an earthquake and not by a fire—and favored the settlement of Troya VII-A, where there is a thick layer of ash and charred remains that can be dated to around 1200 BC. Among the vestiges found in this layer are remains of skeletons, weapons, deposits of pebbles —which could be ammunition for shooting with a sling— and, interpreted by some as very significant, the tomb of a girl, covered with a series of provision vessels, an indication of an urgent burial due to a siege.

In addition, the date of its end is not far from the dates established in Antiquity by Eratosthenes (1184 BC) and Timaeus (1194 BC), among others. For all these reasons, some scholars point out that the "city of Priam" corresponds to Troy VII-A, despite the undoubted artistic and architectural inferiority that distinguishes it from the preceding one.

- Troy VII-B-1

In the successive level of Troy VII-B-1 (approximately 1200-1100 BC) remains of barbarian pottery were found that were not made with a wheel but by hand and with coarse clay. Due to similar findings that have been found in other areas, it has been assumed that a foreign people from the Balkans settled at this time. In addition, the city shows a large accumulation of burned land, up to 1 m, from large and repeated disturbances, which did not interrupt the continuity of life in the city, where the walls and houses were preserved. From this it has been deduced that during this time there were at least two fires and one of them caused the end of this city.

- Troy VII-B-2

The most obvious sign of a new component in the social and cultural order is represented in the Trojan level VII-B-2 (1100-1020 BC) by ceramics called knobbed ware (although pottery remains similar to that of the previous stage and even a few remains of Mycenaean pottery have also appeared) with decorative protuberances in the shape of horns, already widespread in the Balkans and probably the inheritance of recently arrived people, peacefully infiltrating the region or product of cultural exchanges between Troy and other foreign regions. The construction technique also varies considerably, with walls reinforced on the lower courses with monumental orthostats.

In 1995, a written document consisting of a bronze seal showing signs of a writing system for the Luwian language called luvioglyphics was found in this layer. It was deciphered in its special sense, finding that on one of its faces it contains the word scribe, on the reverse the word woman and, on both sides, the sign good. For all these reasons, it has been assumed that the owner of the stamp must have been an official official. Troya VII-B-2 went down in a fire probably due to natural causes.

- Troy VII-B-3

The differentiation of this stratum with the previous one is due to the archaeologist Manfred Korfmann, who defends that after the end of the previous city there was another colony that must be distinguished from the previous one, characterized by the use of protogeometric ceramics and that disappeared around 950 B.C. C., leaving the place almost uninhabited until the year 750 a. C. or 700 B.C. C. Faced with this, Dieter Hertel believes that the Greeks were already established in Troy from the end of Troy VII-B-2.

Troy VIII

The history of Troy in ancient Greek times does not go back much further than the 7th century BCE. C., as it occurs with the other numerous testimonies from the northwestern area of Asia Minor and from Byzantium itself. For about 250 years, between 950 B.C. C. and 700 B.C. C., the Hisarlik hill must have remained almost uninhabited, although some authors such as the aforementioned Dieter Hertel argue otherwise.

In Troy VIII a flourishing architectural activity appears, especially religious: the first great cult building of the time discovered, the so-called upper temenos (enclosure), still preserves a solemn altar in the center and another, from the time of Augustus, on the western side. The lower temenos follows, with two altars, perhaps for sacrifices to two divinities, both unknown. The sanctuary of Athena, whose origin could date back to the 9th century B.C. C., was converted into a great temple, of rigorous Doric order, in the III century B.C. C. For this, and for the construction of the stoa, some buildings of the acropolis of previous times were demolished.

Some archaeologists place it in the 3rd century B.C. C. the beginning of Troy IX, in discrepancy with the chronology proposed by Manfred Korfmann.

Troy IX

Troy IX (Ilium Novum, or New Ilium) was the Roman city that emerged after the destruction of Troy VIII by Fimbria, one of the men of Gaius Mario (86 BC-85 BC). The Iulia gens, Julius Caesar and, to a greater extent, Augustus, enriched the city of Troy with temples and palaces, and enlarged the temple of Athena, which was surrounded by monumental colonnades (80 m on each side), and provided with an imposing propylene. This Roman settlement extends partly over the plain at the foot of the hill, while the acropolis maintains its character as a place of worship with the temple of Athena. Some sections of the wall, the baths, the bouleuterion, a theater and some houses remain from this phase.

Trojan X

Korfmann gave this name to the layer of the few remains that belong to the Byzantine period, between the 13th and 14th centuries, in which Troy was a small episcopal seat. These had already been discovered previously by Schliemann and Dörpfeld.

Gallery

Contenido relacionado

Convent of San Marcos (León)

Frederick William IV of Prussia

27th century BC c.