Trireme

The trireme (in Greek τριήρης/triếrês in singular, τριήρεις/triếrêis in plural) was a warship invented around the century VII a. C. Developed from the penteconter, it was shorter than its predecessor, a boat with one sail, which had three banks of rowers superimposed at different levels on each flank, hence its name.

Triremes appeared in Ionia and became the dominant warship in the Mediterranean Sea from the end of the 6th century to. C. until the IV century BC. C. From these dates it was displaced by the quinquereme, until after Rome's domination of the Mediterranean it was used again due to its effectiveness by the Roman Empire until the century IV.

Despite the initial difficulties in the architecture of the trireme, essentially its dimensions, angle of inclination and path of the oars to which was added the training of the crews to achieve an organized flight, the concentration of efforts allowed a better ship steering and increasing power in short haul sections during combat to employ the bow ram.

The first and most famous naval battle of antiquity in which triremes were used was that of Salamis, in 480 BC. C., which faced the Greek fleet, mainly that of Athens, against the numerically much superior Persian navy.

Introduction

When naval engineers wanted to increase the power and speed of the ship provided with a single bank of rowers, they devised dividing them into two, those on the lower level would row through lateral openings in the hull, those on the upper level above he gives it away. To add a third level of benches there was a lack of space within the hull, and increasing its dimensions would result in a much deeper, much heavier and much slower boat, so it would lose the expected advantages of the third level of rowers. Between 550 and 525 BC. C. the solution was found: an external platform (parexeiresía: «auxiliary device for oars») was added, projected laterally beyond the dead work. In this way, space was achieved for a third bench of rowers without profoundly modifying the general line of the hull.

The construction and maintenance of naval forces in classical Athens, with the aim of preserving naval supremacy and thereby gaining control of navigation in the Aegean Sea, involved the creation of an enormous financial and logistical mechanism. Much of the economic and social life in Athens was directed towards the maintenance of the fleet, which at its peak numbered around three hundred ships.

The trireme appeared in a context in which little by little the tactics of naval combat had slowly evolved, going from fighting to boarding to the use of the ram. This change is significant at the moment when, to fight with the ram, the key factor is not the training of the hoplites for hand-to-hand combat, but the ability to maneuver and the speed to find a favorable position in the way of ram and disable enemy ships. The weapon par excellence of the triremes in classical Greece was, therefore, the ram or plungers, and that navy that most and best perfected the training of the crew members and the characteristics of the ships was the one that obtained mastery of the sea.

Discussion on origins

The first three-tiered warships probably originated in Phoenicia: on a fragment of a relief from the 8th century a. C. found in Nineveh, the Assyrian capital, and which represents the fleets of Tire and Sidon, vessels have been identified whose interpretation is that they represent warships of two and three levels, equipped with rams. Likewise, the 2nd century scholar Clement of Alexandria, based on earlier work, explicitly attributes the invention of the trireme (trikrotos naus, "three-tiered ship") to the Sidonians.

Pliny the Elder and Diodorus Siculus write that the trireme was "invented" in Corinth. Thucydides says that the Corinthians, in the VII a. C. were the first to deal with naval construction with techniques very similar to those of the V century BC. C. time in which the Athenian historian wrote. According to him, the Corinthian shipowner Aminocles would have invented the trireme, building it around the year 704 BC. C., four for the Samians. The Spanish historian Juan José Torres Esbarranch agrees on this date in his translation of this passage from the History of the Peloponnesian War, in which Thucydides adds that the invention was "three hundred years before the end of our war." He leans towards this year, considering that the Athenian historian refers to the Peloponnesian War in its entirety (up to 404 BC) and not to the end of the Archidamic War (421 BC).

The date of 704 BC. C., being considered excessively high, has been discussed by modern researchers of the marine in Antiquity, who maintain a date close to that of Thucydides, but lowering it by about 50 years. His hypothesis is that in the VII century BC. C. the transition from the bireme to the trireme must have been made, the use of which spread slowly from approximately 650 BC. C. Other authors have their reservations about it.

According to J. Taillardat this date of 704 BC. C. is based only on the testimony of Thucydides, who in this same passage objects to the vague information he has from tradition regarding the origins of the trireme. Thucydides says he knows from good sources that the first known naval battle, fought between the Corcyraeans and the Corinthians, occurred about two hundred years before the date indicated by Thucydides, that is, around the year 664 BC. C., calculated from 404 BC. C. The fragility of this testimony was studied by J. A. Davison in 1947, who reached the following conclusions: in the Greek fleets, the trireme appeared for the first time in Ionia, towards the middle of the century VI a. C., at the earliest. Hipponax was the first Greek author to mention the trireme, and Polycrates of Samos was the first ruler to adopt the trireme. At the beginning of his tyranny he had 100 Penteconters and around 526-525 BC. C.—seven years later—the bulk of his fleet was made up of triremes. Critics consider that the mention of triremes when Herodotus has alluded to penteconters when talking about the naval potential of Polycrates is an error, since in passages III.41.2 and III.124.2, penteconters are always referred to, not triremes. In the same sense, cf. Thucydidesop. cit. I.14. Herman T. Wallinga goes further to say that Herodotus uses the Greek word τριήρης (triere) as a generic term for "sea-going vessel", in the original. Carlos Schrader emphasizes that Herodotus did it "possibly intentionally."

However, the penteconter, due to its structure, was not very suitable for long voyages. Given the exaggerated number of triremes, it would be possible that they had been captured from Phoenicians or in regions commercially related to Phoenicia, if the Phoenician origin of the trireme is admitted, as Lucien Basch does.

The Greek belief about the Greek origin of the trireme is understandable by the fact that at that time the Corinthians, taking advantage of the advantageous location of their polis (city) that controlled the entire Isthmus that unites the Peloponnese with the rest of Greece, were expanding their commercial domain thanks, among other reasons, to their fleet.

The controversy over the precedence of the Greek triremes over the Phoenicians has opposed two researchers. According to Thucydides' chronology, A. B. LLoyd's analysis gives precedence to the Greek one. For Lucien Basch the invention would be Phoenician, and this would have served as a model for the Egyptian one. They maintain an intermediate position E. Van' t Dack and H. Hauben, who claim that the trireme was a Greek invention and that Pharaoh Necho II did not build it in the original form, since his naval engineers were Phoenician.

Development

The diffusion of this type of ship, which replaced the penteconters, was a rather slow process, since they were not especially difficult or expensive ships to build, by comparison, but because they required an investment in human resources (and therefore both financial) that took a while to become available. It was initially adopted in the arsenals of Tire and Sidon, at the mouth of the Nile, in Corinth and even in Syracuse. At the naval Battle of Lade (summer 494 BC) the Greek fleet consisted only of triremes.

The obstacle posed by the absence of representations in Greek ceramics of the time would be overcome by considering that the trireme had not replaced the penteconter as the main warship, a fact that occurred later until reaching the century V a. C., when the trireme became the fundamental ship of the Greek armies. The Greek author Polyenus makes express mention of the trireme as a warship that constituted the fleet of Gelón, who in 480 BC. C. gave an account before the Syracuse assembly of the expenses incurred in the war against the Carthaginian Hamilcar Magón, among which were "those generated by the triremes." During the Persian Wars of the century V a. C. the warship par excellence was already the trireme, not only on the Greek side, but also on the part of the Persians.

The hegemony of the trireme in the Mediterranean fleets spans the centuries V and IV a. C., until they were surpassed by the large galleys of the Hellenistic era (See Navy in Ancient Greece#The temptation of gigantism). However, the trireme continued to be used well into our era, as an exploration or escort ship, although heavier and oriented toward boarding combat.

In Athens

At the beginning of the V century a. C. the Athenian fleet was equipped with a few triremes, since the bulk of the fleet was made up of penteconters and triaconters. But the war that it was then waging against the Aeginetans and the Persian danger that remained after Marathon, prompted it to modernize its forces. naval. The fleet that defeated the Persians in the waters of Salamis had been built by the strategist Themistocles.

The discovery at the end of the VI century a. C. in Maronea and in Laurion of important veins of silver, provided the opportunity for Themistocles: in 483 BC. C. he managed to convince his city of the need to renew the fleet and in just over two years he launched a vast renovation program, financed by the noble metal extracted from the mines:

...when the Athenians in view of the fact that there were large sums of money in the public court, which came from their Laurion mines, they were ready to be distributed among all on the basis of ten drachmas per head. So, Temístocles convinced the Athenians to stop this casting and, with the sums available, build two hundred warships (above the conflict with the egyptians)Herodote, op. cit. VII.144.1-2

In 480 BC. C. in the Battle of Salamis, between 150/180 of the 310/378 triremes deployed by the Greeks were Athenian. According to Herodotus (History VIII), Athens provided 180 triremes (VIII.44) out of a total of 378 (VIII.48). Whatever the accepted figure, the authors agree on the fact that the Athenian triremes represented half of the galleys of this type present in the battle. But these ships, which were among the first of this type in the city, "did not yet have bridges along their entire length." According to Plutarch, it was Cimon who, on the occasion of the Battle of Eurymedon (467 BC), ordered the bridge to be joined from bow to stern to enable an increase in the number of combatants and give more offensive capacity to the triremes: «Cimon made them wider and equipped them with steps between their bridges, so that, loaded with many hoplites, "They behaved more effectively against their enemies."

The speed of the trireme, its solidity in relation to the longer previous models, facilitated its construction. It was the instrument that allowed Athens to extend its hegemony at sea during the course of the V century BC. c.

Subsequent developments

Although the Athenian fleet lost its superiority when it was defeated during its expedition to Sicily by Syracuse, Sparta and their allies, in the Battle of the Epipolae, (in 413 BC, during the Peloponnesian War), the triremes However, they continued to have control of the seas. Dionysius I, tyrant of Syracuse, provided his city with larger and heavier quadriremes and quinqueremes during the first years of the following century. The decline of triremes occurred during the Hellenistic period, when each important nation built galleys such as the quinquereme, whose tactics were based on boarding and artillery, disorganizing the opponent's rowers. The Roman navy perfected this technique with the use of the corvus.

The trireme continued to be used as an auxiliary to larger units. Already in the time of the Roman Empire it became predominant due to its lower cost and because control of the seas was assured.

Over the centuries, the trireme saw few modifications: in most cases, the size of the bridge was increased along the entire length of the ship and from the century onwards V a. C. panels were fixed to protect the rowers from waves and arrows. The rig was sometimes composed of one mast, and other times of two. In the course of the IV century d. C., gave way to the liburnas, less fast but lighter and more agile, which were the origin of the Byzantine dromons.

Construction

There is no archaeological evidence of what exactly a trireme looked like, since the remains of ancient shipwrecks are overwhelmingly civil ships. The pieces of wood have positive buoyancy, and the submerged wrecks belong to cargo ships, because the weight of the cargo has kept the remains underwater.

Archaeologists and specialized historians admit that the construction system was the same for triremes and "longships" (warships) with oars.

In the Athens of the V century BC. C., the information regarding the time required to build a trireme is not clear. The references we have are limited to knowing that the Maronea mines were discovered in 483-482 BC. C. and that the Battle of Salamis was in September 480 BC. C, and in that interval, Themistocles ensured the construction of at least 200 triremes.

Triremes still existed in 323 AD. C.: Licinius gathered a fleet of 350 triremes against Constantine I, who had 200 triaconters. In the narrow waters of the Hellespont, 80 triaconters were enough to defeat Licinius' 350 triremes. The defeat of Licinius marked the defeat of the trireme as a warship. At the end of the IV century, a large part of the knowledge had been lost:

(...) but many years ago they have forgotten the methods of construction of the trirreme».Zosimo, New History V.20

Dimensions and shapes

Thanks to the discovery in 1885 by Dragátsis and Wilhelm Dörpfeld of covered sheds in Zea (one of the military ports of Piraeus), and the excavation campaigns carried out since 2000, we have a fairly precise idea about the dimensions of a trireme. In the stone sheds, the arsenals where the triremes were housed when they were not sailing were discovered. The iconography also provides some evidence of its general shape, but does not allow us to determine the construction method used. It has been hypothesized that the construction method was the same as that used in the merchant ships that have been found. This hypothesis is merely indicative, since there are arguments against it, since throughout the history of shipbuilding there are many examples in which the construction technique of warships is totally different from that of cargo ships.

These ships were about 36 m long, and had a beam close to 5 m. The height under the roof of the ships was 4.026 m, and the height of the hull out of the water is estimated to have been 2.15 m. The draft was smaller, just 1 m (to facilitate the beaching and dry laying of the hull), as attested by the texts that mention the hoplites coming from the beach and boarding the ships afloat: «(...) The Messenians who had come to help and, entering the sea with their weapons, had climbed aboard, fighting from the bridges managed to snatch them from them when they were already being towed." The length-to-beam ratio was, however, very high (10 to 1)., which made the ship go very fast.

Its ability to approach very close to the coast is explained by the practically flat bottom, without a keel. The rounded shape of the stern, characteristic of ancient ships, helped this maneuver since the trireme was facing the sea.

The historians M. P. Adam and J. Taillardat also believe that the raised back part would be the consequence of a construction technique: the planks were rectangular (they only tapered at the ends), which forced them to be arranged this way. The assembly method is not subject to any certainty. Specialists such as J. Taillardat assume that they were fitted together by a system of tenons and notches, finally reinforced by pegs; technique known since Homeric times,

Based

The lexicographers have transmitted the names of the main parts of which the base was composed, such as the δρύοχοι: *for Suidas and Zonaras the estais that were used during the construction of the ship. According to the Etymologicum Magnum "they are vertical pieces of wood that support the keel while it is being built." Eustathius of Thessaloniki understands that "they are the ones arranged in a row and on which the keel of the ship under construction rests.", so that it has a regular shape." He adds that they maintain the hull on both sides and surround it with continuous supports. Plato says that they are "supports that serve during the construction of the ship." Hesychius of Alexandria defines them as "pieces of wood that support the keel of the ship."

Helmet

The hull was made up of the keel, the port and starboard sides, the battens, the planks and the gunwales. The hull construction method is the usual one in ancient times, known as shell-first, that is, "shell first". It consists of first building the exterior planking, assembling the pieces together using a box-and-tenon system and wooden pegs, and overlapping them, which are joined to the keel and the figurehead, reinforcing it from the inside using wooden frames (ribs) and beams (transverse beams). The longitudinal elements were joined by anchors and covered with a lining of plates placed edge to edge, instead of overlapping.

To keep the hull together, it was tensioned using a very thick rope called hypozoma, safely located inside the hull, crimped to the stem and stern, and tensioned with a kind of windlass amidships; Some engineers believe, on the contrary, that this thick rope surrounded the hull on the outside. Each trireme carried four of these spare ropes, as specified in naval records and required by Athenian military ordinances. For long journeys, six ropes of this type were placed. It was one of the most important pieces of the ship. Plato alludes to it by calling it "the bandage of the trireme." A trireme was described as banded when equipped with hypozoma. In an Athenian decree mentioned in an inscription it is prescribed that the minimum number of men necessary to place a hypozoma was fifty.

The solidity of the ship was a fundamental factor since it was fought with a ram blow, and the hull had to be prevented from breaking upon impact with the enemy ship. However, the strength of the hull must have been secondary to the Athenians, seeing the great emphasis they placed on the lightness of the construction.

The ledge or buttress where the upper row of rowers (the tranitas) was located was locked with the side of the hull by means of transverse stringers: above the tranitas there was a cover that extended from one side to the other and on which there was a walkway, which in turn extended along the length and served more as a maneuver and protection platform than as structural reinforcement.

Spur

A bronze spur (plungers) was placed on the beam, intended for ramming maneuvers, a tactic that became widespread due to the ship being so agile. It was located at the level of the waterline at the bow, in order to inflict the greatest possible damage and thus sink the enemy ship.

It was lining the front tip of the keel, armored and built with three sharp blades that were just above the water level. The shape of the joint between the spur and the bow post, which curved upwards and forwards, allowed the resistance of the water to be reduced so that the structure acted as a weapon and as a water break.

It could punch a hole in an enemy ship and render it useless, but it did not sink it immediately. Ancient sources use terms that mean "sink," but it was possible to tow ships that began to sink in this way. The Greek word kataduein means "to immerse" or "to descend."

After the naval battle of Syvota (433 BC) the Corinthians did not tow the triremes that they had disabled, but they could have done so, according to Thucydides: «...the Corinthians did not bother to tie down with cables and tow the hulls of the ships that had damaged, but going from one side to the other they headed against the men, more to kill than to take prisoners.

Ancient sources teach us little about the spur. Eustathius says that it was located in the bow and that it had a pointed shape. The scholiasts of Thucydides and Hesychius say that it was a copper device fixed to the bow of the ship. Suidas and Zonaras add that it was made of copper subjected to action. of fire (πεπυρωμένον). But copper is a weak metal and was replaced by iron.

Bow

The bow of the trireme was called pora (πῶρα). On each side of the beam there was a thickening located below the waterline; It was the "shoulder." Above was the "cheek": rounded part of the hull between the mizzen mast and the bow. Pollux says that each of the halves of the bow was called cheek or "wing". For Hesychius, the Homeric expression elteareaoi (μλτπάρηοι), is the cheeks colored in vermilion. According to Herodotus "in ancient times all ships were painted with minium."

The hawse (ὸφθαλμός) was represented by an eye with its pupil, eyelids and eyebrow. Some coins show at least two hawsees on a single side of the ship, situated on different levels. Jal reproduces the prow of a ship from Pompeii, painted in three quarters, which reveals two hawsees, one on each side of the bow. According to Pollux "there is a part of the ship called ὀφθαλμός and πτυχίς. It is on which the name of the ship is inscribed." This too concise explanation has misled commentators, who have confused the badge that bears the name of the ship with the hawse. It is the eye of the animal, as as it appears on the ancient coins of Samos. It is in painting that the hawse was given this eye shape, which has been preserved in a large number of monuments. Over time the hawse was reduced to being a simple opening to make way for the anchor cable. There are different legends and notable differences in the representations of the hawse on the coins of the seafaring polis. In Athens, the hawse of the trireme seems to have been provided with a metal protection around its entire perimeter to prevent wear caused by the friction of the cable.

Before the Second Battle of Syracuse Harbor (summer 413 BC), the Syracusans made modifications to the bows of their triremes. They reduced their length to give them greater solidity, according to Thucydides:

"they gave them thick servioles to the proas and, starting from the serviolas, they fixed some tips that were introduced into the amuras and had an extension of about six cubits inside and outside. In the same way the corinthians had adapted the bow of their triremes to fight against the Naupacto fleet. And the Syrians thought that in that way they would not be at a disadvantage in front of the Athenian ships, which did not oppose the same form of construction, but they had the most sharp part of the bow, as they did not practice the front tactic of the frontal clash, proa contra proa, as the one to perform a rodeo manoeuvre to embed laterally with the spurs; they also thought that the battle in the port »Tucídides VII.36.2-3

Torres Esbarranch says that «these struts or counters (antērídes) would be two arched beams that reinforced each serviola in case of an attack. They started from the bulwarks and ended in a transverse beam.

Herodotus, speaking of the Samians of the time of Polycrates who were defeated by the Cretans and the Aeginetans, says that the latter tore off the prows of the enemy ships that were shaped like a boar's head (προτμή). The terms for designate these bows, of primitive construction, subsisted in the Athenian navy of the centuries V and IV a. c.

Other pieces of the bow were the epōtídes (ἐπωτίδες), which served to suspend the anchor; They were the equivalent of modern davits. Euripides, when talking about the various maneuvers that took place during the departure of the ships, says that "they served to complete the defense system of the bow." Pollux limits himself to naming them, saying that they were also called amphotides (ἀμφωτίδες). They are defined by the scholiast of Thucydides (II.34.5) and by Suidas, as the pieces of wood that form the projection on each side of the bow: ἑχοντα ξύλα». They were supported externally by stays in the flank of the ship and flying buttresses inside: this system of flying buttresses was called ἀντηρίδες. The flank of the trireme was protected by the ἐπωτίδες which, forming an overhang in the bow, just at the height of the parodos, they stopped the enemy by digging into their gunwales and reducing the deadly nature of the impact of the spur. The scholiast of Thucydides (VII.34.5) says that there were two stays per epōtíde, one inner and one outer, whose foot was supported on the gunwale, to the upper part of which the epōtíde was attached. . The Thucydides passage (VII.34.5) partly makes the usefulness of these strong projecting beams understandable. In the trireme seen from the front, the epōtídes formed like two ears and completed the prow with a head of animal.

The triremes had two delicate and fragile parts on both sides: the outer gallery called πάροδος (parodos) and the set of oars. It was enough, even without boarding the trireme, to pass in the opposite direction at a very short distance to break its oars and its parodos and thus be able to put it out of combat. The parodos It was not protected by epotides, but the upper part of the hull lengthened and widened towards the bow. As it protruded, it was supported by corbels. Seen from the front of the nave, this widening completely covered the parodos.

The bow stem was crowned by a structure called στόλος/stolos, which ended in the acrostolium (ἀκροστόλιον).

Stern

To refer to the stern in Homeric Greek it was said πρυνᾕ ναῦς. According to Eustathius of Thessalonica, πρυνός means "what is behind", in reference to the rear part of a ship. In classical times it was designated with the word πρύμνη.

It had a physiognomy as characteristic as the bow. There is no correspondence with certain details of its construction in the modern navy. The bow and stern were not differentiated as markedly as in the navy of recent centuries. Here is the reason: a sailing vessel can, as needed, lean to starboard or port, but it is impossible for it to stop and instantly change direction like a rowboat or steamboat. If the shipbuilder gives the bow fine shapes so that it easily breaks the waves, the stern can be lengthened. Thanks to their square stern, the galleys of the 18th century were true floating houses; On the other hand, the trireme was a combat device and everything was arranged so that it would respond as exactly as possible to that purpose. Its stern was thin and fine like the bow, so that it could maneuver freely, and would march backwards at the first signal. given to the rowers. In the monumental representations it can be seen that the Greek ships with a ram generally had the bow more sunken than the stern: the bow, due to the ram, was built more solidly, heavier and had more draft. As it was the part destined to crash into enemy ships, it had to be more robust and heavier. On the other hand, the stern could be lightened: the sternpost formed an obtuse angle with the keel and rose in an imperceptible curve, so that during a landing the ship could be beached on a sandy beach, inclined on a gentle slope. sternpost, at the height of the bridge, on which a set of pieces was superimposed that were joined vertically, then forming an incoming curve towards the interior of the ship. From the extremity of this extension of the sternpost started a series of light decorations called aflastas (ἄφλαστα), which extended above a part of the sterncastle.

The aphlasts were to the stern what the acrostolium was to the bow: the first were at the crown of the stern, the second was at the extremity of the στόλος. The shape of the aflasta, according to Pausanias, following Eustathius of Thessalonica, who quotes Didymus of Alexandria, rises at the stern. It was composed of recurved boards with which another board was crossed that joined them and rested on a support fixed behind the helmsman. The pennant that was the emblem of the ship was suspended on these boards and on the transversal that joined them. According to Pollux, the aphlastas were the end of the stern; Below them was a vertical piece of wood, in the middle of which was suspended a pennant called ταινία.

Around the stern extended a gallery analogous to those that decorated the galleys of Louis XIV and Louis XV, but naturally simpler. This gallery is visible on a merchant ship from Ilercavonia. According to Pollux, these galleries or perhaps simply the projecting pieces that supported them, were called by the Greeks περιτόναια.

Rudders

The system used by the Greeks to direct their ships differs completely from the current one. Instead of a single rudder hooked to the sternpost, each ship had two spat rudders, as they appear in the figurative monuments and as attested by Naval Inscriptions. They were located in the stern, one to starboard and the other to port. They were called πηδαάλια, οἴακες, αὐχένες: the three terms were synonymous and used interchangeably. They were usually said in the plural. However, there was a primitive difference between these words in terms of meaning, as Eustathius of Thessalonica indicates when speaking of πηδαάλια.

Some people consider it synonymous with this word the word of α.χ, as the usual term α.χιον.

The following gloss is found in the Lexicon rhetoricon: οἴαξ. πηδάλιον αὐχήν. The author adds that Diogeniano understands by οἴακες, the wheels that move the rudders, that is, the rudder stock, which is rigid, and joins the shaft and the washers through which the transmission ropes pass, and also joins the tiller. to the shovel of the same. Of the nautical terms it is in fact, that of οἰακια, whose meaning is wooden wheels, the means through which the spat rudder was rotated. Thus, according to Eustacio, although the two words were used interchangeably, The proper meaning of οἴαξ is that of the rudder. Zonaras understands by οἴακες the pieces of wood adapted to the rudders to make them maneuver, which were at the helmsmen's hand. The helmsman's position was called σκηνή.

Materials

Plato speaks of the trees essential for its construction: the fir, the pine and the cypress.

Theophrastus comments that in the construction of the trireme the use of fir wood was common and he recommends the use of this conifer due to its lightness. The philosopher includes the statement of some authors who say that the wood sometimes used for triremes was spruce, in case they did not have fir wood on hand; that of larch due to its light weight for the internal parts. Hard woods, such as ash and elm, were used for the proel posts, as well as oak for the keel, so that it could withstand the tow. The Syrians and Phoenicians used cedar, given the scarcity of spruce in their lands.

The rounded parts, such as the outside of the keel to which the deck was attached, and the anchor beams (ἡ ἄγκυρα) were made of orno, moral and elm, since these elements needed to be strong. Some, like the Cypriots, built these parts with Aleppo pine wood, even though it rots quickly.

The wood usually came from Thrace and Macedonia, since there were no quality forests in Attica. There were agreements between the Macedonian kings and Athens to import wood or for Athenian shipowners to build their ships there.

Since the treatments to preserve the wood of the hull from the hoax attack were not very effective, it deteriorated quickly. To avoid this, it was common for the Athenian ships to be removed from the water and left dry in the arsenals of Piraeus.

Caulking, that is, waterproofing the hull, was done by introducing pitch or wax into the interstices of the planking. The caulking deteriorated over time and needed to be renewed every time the ship was laid dry. That was the time when the shipyard operators also took the opportunity to careen the hull, that is, clean it of adhesions (algae and other dirt) so that the speed would not be reduced due to the greater hydrodynamic resistance of the hull. Once the hull was caulked and faired, we proceeded to paint it.

The question of parexeiresíai

The parexeiresia (ancient Greek παρεξειρεσία) was the projecting part of the trireme between the rowers and the gunwale, a structure that protruded from the sides of the triremes, next to which the tranites were located (θρανῖται, thranîtai). They were longitudinal pieces of wood that supported the oars of these rowers, located at the end of the bow and stern. Hesychius of Alexandria points out that "it is as if it were said to be beyond the oars" (...ώσεί λέγοι τις εἰ ρεσία). Ancient lexicography only presents this testimony, the first chronologically, which has been copied in everywhere. This term, according to J. Taillardat seems to be a compound of ἐξάγγελος, and παρέξ, which would play the role of an adverb. In this context παρξειρεσία means "port rigging that is outside and along the ship." It would designate and be equivalent to the apostis of the French galleys of the XVII and XVIII. In the absence of literary or iconographic references, historians have not been satisfied with this hypothesis until recent times. For a long time it was assumed that the trireme had the appearance of a penteconter, to which two overlapping rows of rowers would have simply been added and with the hull noticeably smooth on the outside.

For a new study of the set of documents, the most precise iconographic source is the Lenormant bas-relief. Based on the experience of modern galleys, it is now almost certain that the parexeiresíai were located about one meter on the outside of the hull. The tranites' benches were located at the level of the lower planks.

J. Taillardat, relying on the following four texts and, to a lesser extent, on the figurative remains, tries to provide the meaning of the term:

- (a)

against the rash of the waves under the parexeiresía of each embroidery (πρòς τ),ς πιβολ),ς τ),ς τ),ν χυμάων σπ),ρ τ),ν παρείιρίαν),χατρσυ τοου), Cabrias stretched skins without curling against the waves on one and the other side of the bow and, firmly clinging them to the top of the bridge, and brought them down vertically to the parexeiresíai, to skeleton (φργμα). This prevented the ship from becoming heavy, the masts from breaking, and the sailors from being soaked by the waves; and as the waves did not come, thanks to the protection of the skirts, fear did not make them rise to the plumbers, and thus prevented the ship from breaking.Polyene, Stratagems III.11.13

- (b)

In a short time, the wind caused the sea to grow and that, on the embroidery, water would come in abundantly, not only by the tolet gates, but also by the the parexeiresíai (,ς μ, χατά εις χ,παος μόνονον, εισον, κισρείαν, είας ειρειρειρεεισρενν μμ ν σχατπρωειεν εν εν πεν εν εν πριεν εν πριεεν εν εν πριεν ειειεν πριειεν εν εν πριειειειειειειειεν εν εν πειειειειειειειειειειεν εν εν εν εικειειεικεν εικεν εικεν εν εικεικεν εν ενFlavio Arriano, Periplo del Ponto Euxino 5

- Regarding the Huns adapting their armies to maritime navigation, Agatías says:

- (c)

that they installed toletes on each embroidery, a kind of parexeiresíai provisional (χωπιεειρειρίας α)τομάτος κεειρειρίας α)τομάτος /25070/μίος הμχειαντοντον)Agatías, Stories V.21.

- (d)

Cabrias had two timons for each triere for marines in the high seas, and in the storms he used the current, but if the sea was growing, the other passed through the parexeiresía, by the rows of the tranitas, (θάτερα [scil. πηδάλια] δικς παρείαρειρειρίας παος παρετειειειια) with the throat and rings on the bridge, so that when the pope was lifted, the ship was directed with it.Polyene, op. cit. III.11.14

From these four passages the following conclusions can be drawn: there was a parexeiresia on each edge of the triere (cf. texts a), b) and c). Contrary to what ancient lexicographers claimed, there were rowers—and, therefore, oars—in the location where the parexeiresia was located; This is clear from text a, sub fine: It is certain that the parexeiresia carried batons (cf. c). The parexeiresía above the ports (cf. b), in the place of the oars of the tranitas (cf. d), which is also known to have constituted the first row of oars.

The παρεξειρία had to be "the rig of the poles that was outside and along the triere", that is, its apostis, the πάροδος, the passage. In short, it would be the protruding part on either side.

However, Morrison and Coates point out that it cannot be said that there is a clear indication in the Athenian Naval Inventories and in literary sources about the alleged connection between the Tranites and the parexeiresíai.

The oars

The question of the position of the parexeiresíai is closely linked to that of the oars: if these supports were attached to the hull, the oars of the highest row had to have a greater length in order to to penetrate the water in the same way and without intersecting with the lower levels. Now, the general of the galleys of Louis This need, drawn from experience, confirms the currently adopted model of the amplitude of the parexeiresíai on the outside of the hull.

Each oar was handled by a single man: "the plan was for each sailor to take his oar, cushion and strobe." The cushion was to serve as a seat, not so much to protect the rowers' buttocks as to prevent them from slipping., especially when they rowed hard. The strobe served to keep the oar at the level of the apostis. The oars had a length of 4.17 m. Some ancient authors indicate that in the center of the ship the sailors of the three rows operated the longest oars, which measured 4.40 m, practically the standard length of modern canoes. The oars used in the bow and stern were slightly longer. short ones measured 4.10 meters.

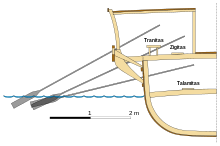

Naval records report that each trireme received 200 oars: 170 for the three banks of rowers, and 30 for the two dimensions, as replacements. Looking at a trireme from the flank, it seems that the general scheme was arranged in the shape of a quincunx.. However, the usual thing was the grouping of three oars in an oblique row: the oars of the Tranites, Zygites and Thalamites formed, in a given segment, the fundamental unit, from which comes the name triere, "with three rows." There were 27 of these units on each side, to which were added two small boats rowing alone in front and behind.

Fifteen.

Fila oblicua.

The direction of the ship was carried out by means of a rudder, a type of oar, which due to its different shape, was maneuvered from the stern. In bad weather the trireme was equipped with two rudders, the second located in the bow.

Cabrias had two helms for navigations on the high seas, and in the temporary and calmly chicha he used the current, but if the sea crespaba passed the other through the prow by the top rows with the throat and rings on the bridge, so that when the stern was lifted, the ship was directed with it.Polyene, Stratagems III.12.14

This did not exclude that there were ships with the two steering systems located together at the stern.

The masts and sails

Although it is known that the Roman trireme had two masts, the main one vertical and located in the center, and a second one in front and inclined, specialists have doubts as to whether the Greek one had them.

According to texts from the classical era, at least from the end of the V century BC. C. and until the year 352 BC. C., these ships were equipped with two masts: a mainmast (ἱστός μέγας) with its square mainsail (ἱστίον μέγα) supported by a yard of around 22 m wide and 8 m high; a second mast called ἱστός ἀκάτειος with its sail called ἱστίον άκάτειον. The akateion always remained on board; It was used for rough seas or for escape during a battle, especially if the trireme was unable to maneuver by oar due to the damage inflicted. In anticipation of a naval combat, the main rig was deposited on land, as it was too bulky for a narrow boat, and so that the movement would not be at the whim of the wind. That the size of the akateion was smaller than that of the mainsail is indicated by the opposition of the terms μέγας/ἀκάτειος, and is confirmed by the fragment from Epicrates the Comicus: «abandon the vessels and raise the great cups", joke for the play on words "carries the akateia and raises the main sails" Aristophanes was the first author to mention the akateion sail; the second It was Xenophon in 373 BC. C.; and thirdly the Naval Inventories of Athens from 356 and 352 BC. C. From a quote from Herodotus it is inferred that it would already exist at the beginning of the V century BC. C. In 330 BC. C. the mast akateios and its sail disappeared from the Athenian inventories.

About the use of these sails, Xenophon says that: «Iphicrates... prepared everything for naval combat... he left the main sails in Athens, sailing as if he were going to fight, and he made little use of the small sails (akáteia histía) even if the wind was favorable; Because by rowing he managed to keep the men physically better and the ships to run better." It follows that the sail akateion was kept on board without hoisting it. This explains that in the spring of the year 413 BC. C., after the Syracusans were defeated by the Athenians in a naval battle in the Great Port of Syracuse, the Spartan general Gylippus, by occupying the Athenian forts of Plemirio, "captured considerable booty, since as the Athenians used the strong as a warehouse, there was there... a lot of material from the trierarchs, since forty trireme sails were even taken with the rest of the rigging..." In 405 BC. C., Conon, who escaped the disaster of Egospótamos by fleeing with 9 triremes, "after he realized that the situation of the Athenians was lost, he stopped at Abárnide, the promontory of Lampsacus, and there he seized the great candles (τὰ μέγαλα ιστία) by Lysander»

Consequently, in the course of the battle, only one sail (the akateion) was available and it was only hoisted to flee: thus the Samians in Lade (summer of 494 BC.) «in accordance with what was stipulated with Éaces, they hoisted the sails and abandoned the formation heading towards Samos ς τὴν Σάμον)»; for Epicurus, at the end of the century V a. C., τὸ ἀκάτειον αἵρεσθαι "to raise the akateion" is a phrase exactly synonymous with φεύγειν.

On how the akateion was used in situations other than those of a naval combat, only hypotheses can be made:

- I First hypothesis: the trirreme simultaneously used the main sail and the akateion, which meant two masts raised simultaneously. In this case:

- a. Was it two vertical and parallel masts? The question is legitimate, because, after the discovery of Tomba from the ship in Etruria (1958), it is certain that there were merchant ships in the Mediterranean with two vertical masts.

- b. or the akateion it was kind of a square candle paired under the bauprés (the artemon of the Roman warships), i.e. a small square evening located above the prow and suspended from a short and tilted mast?

- II Second hypothesis: the trirreme used alternatively the main sail and the akateion. La akateion and its mast, they replaced the larger candle and its mast. In other words, the use of the larger candle excluded that of the akateion.

No text supports the first hypothesis (I a. and b.). On the contrary, Epicrates the Comic orients towards the second possibility considered, whose quote in a fragment has been recorded in the second paragraph of this section.

In the absence of figurative monuments from the VI and V a. C. representing a trireme under its sail, nothing is certain, according to Taillardat, apart from the word itself: akateios derives from ἡ ἄκατος, which designates all types of ships, small or large; because ἄκατος, contrary to common opinion, is also said of the triere, as Aristophanes shows in The Knights, 761: "hoist the dolphins and put the ship on its side" (τοὺς δελφῖνας μετεωρίζου καὶ τὴν ἅκατον παραβάλλου).

There is uncertainty about the second mast, whose position on board is not known: vertical in front of the mainmast (ἱστός μέγας), inclined as in Roman triremes or replacing the mainmast in its hole during assaults. J. Taillardat leans towards this option. One of the first two hypotheses is not clarified: if the sailors used both sails at the same time, the small mast (histos akateios) must have been the "onboard mast." It was called this way because, unlike the mainmast, it could be stored on board the trireme, due to its small size (although its exact dimensions are not known). This has led to the assumption that the second hypothesis is the good one: the histos akateios with its sail was a temporary substitute for the normal rig: the mainmast and the mainsail.

The small sail and its mast were abandoned in the Hellenistic period, since they are not mentioned in the inventories of the arsenals. This would perhaps be a consequence of the secondary role played by the triremes to the benefit of larger tonnage units. They reappeared in Roman triremes, in which they were located in the front part of the bow.

The mainsail was square, supported by an assembly yard made of at least two masts. The plural noun, ϰεραῗαι ("cocks") designates a single object of complex structure. This sail had no reefs. To reduce the surface area facing the wind, it was rolled up like a blind with briols (terthrioi) that passed through washers (krikoi) fixed on the fabric. Paul Gille, based on the Delos graffiti, estimates that the span of the mainsail was 20 meters long, 8 m high, and a surface area of about 176 m². It is plausible that the akateion was also square in shape, but there is no evidence. The Roman artemon did have this shape. It can be understood that the triere, with its high structures (2.15/2.20 m) and too little height at water level (1 m) was unable to belt the wind, he could only trace zigzags. Regarding this, Xenophon's testimony is available regarding the accusation of Theramenes that Critias makes before the Boulé: "it is necessary, Theramenes, that a man worthy of living must not only be skilled in leading his companions forward in difficult situations, and If an obstacle presents itself, change to the side (εὐθὺς μεταβάλλεσθαι), but hustle as in a trireme, until you get to the favorable wind (ὦσπερ ἐν νηὶ διαποεἵσθαι. ἕ ως ἆν εἰς οὓρον ϰαταστὧσιν). For, otherwise, how could they ever get where they need to, if at every obstacle, they immediately began to sail in the opposite direction? This text proves that the trireme was not zigzagging, otherwise it would be unintelligible.

Normal navigation

To roughly calculate its speed, only one passage from Xenophon's Anabasis is available: ς ἠμέρας μαϰρᾶςπλοῧς, from Byzantium to Heracleia (from Bithynia or Pontica, there are for a trireme a long day of sailing by rowing [or "helping yourself with the oars"?]». Johann Bernhard Graser, estimating the distance between Heraclea and Byzantium at 160 nautical miles and the day of vogue in 16 hours, obtains a speed of 10 miles per hour.

Here, too, doubts remain: there are no details of the means used to propel the ship during navigation. To achieve the performance that Xenophon refers to, historians such as A. Cartault think that the sail was supported by the rowers, since they could not physically maintain the rhythm throughout the day and the exclusive use of the sail did not allow this speed to be achieved.. W. W. Tarn points out that for a galley, 9 miles per hour constitutes a great speed. All the more reason, 10 miles per hour.

Paul Gille carried out some theoretical calculations whose postulates were: waterline length 34 m, hull width 4.30 m, draft 1.10 m, displacement 90 tons, 174 rowers. His results are:

- To row and for a cadence of 18 palates per minute, a trirreme τρκροτος (three levels of rows in action), moved to about 5.2 knots; δκροτος (two levels of rows in action), 4,5 knots; μονόκρος, 3.6 knots.

- Only sail (with an area estimated at 176 m2), the same trirreme developed 5.2 knots with a small breeze (force 3 Beaufort); from 7 to 8 knots when the wind increased.

To sail at 10 knots, the trireme to which Xenophon alludes, had to use the sail and the oars: θεῖν ϰαὶ έλαύνιν, as the Athenians said.

Performance

According to estimates based on Xenophon's statement, a speed of 10 knots was obtained in navigation, which is not materially possible if only one of the means of propulsion was not used. According to calculations, a little more than 5 knots are achieved with the group of sailors at the oars and around 8 knots with the sail in moderate breeze (wind of 20 to 28 km/h).

During the crossings, the rowers' strength was economized, as the same author indicates: «(...) if the breeze was favorable, it would spread the sails and the men would rest while they advanced, but if it was necessary to row, He made the sailors rest in turn.

The Athenian trireme that in the summer of 427 BC. C. sailed day and night between Piraeus and Mytilene, a distance of 355 km (192 nautical miles), was an exception to the norm.

During combat, the trireme was moved by the sheer force of the arms; It can be imagined, in view of the speed reached by the Olympias in the years 1980-1990, that it must have exceeded 10 knots at the moment of greatest speed during the attack with the ram and the cadence of oar strokes increasing during these maneuvers. In the heat of battle it could possibly achieve a speed of no less than 20 km/h for distances less than 2 kilometers.

Crew

The Trierarch

A trireme was financed by a rich citizen or metician, not necessarily a sailor, a member of the class of pentachosiomedimni, and called a "trierarch." He received the ship from the city and was responsible to it, he had to pay for any repairs and the crew's salary when the city could not. He also had to face unforeseen expenses. This liturgy was the most expensive and the trierarch consequently enjoyed considerable prestige in the city, among his fellow citizens. Despite this, it seems that it was not an envied position, in view of the verses that Aristophanes puts into the mouth of Aeschylus in a passage from The Frogs:

"This is what a rich man does not want to be a trieraarch,is wrapped in harapos,

He cries and says he is poor."Aristophanes, The frogs, v. 1065-1066

From the V century BC. C., the trierarchy became too onerous a financial burden for one man and the trierarchs began to group together to assemble a ship: at first two, later several.

Crew composition

During the Peloponnesian War, the Athenian trireme was manned by several different classes of personnel:

- A major state, of which the trierarch was the head, the captain, a charge that could delegate by hiring an experienced marine, who exercised the executive government of the ship and the functions of pilot (kybernétès). The captain was seconded by another officer (proreus), three countermeasures, two toicharchoi (in charge of the maneuvering and unraveling, and responsible for the cargo and equipment of the ship), both under the orders of the comitre (kéleustès), responsible for the direct command of the remeros, the auletes and the trieraulas (trièraulès), flautists responsible for marking the cadence of the palates. He was assisted in his functions by a subcomit (Pentecontars), whose name refers to the command of 50 remeros.

- 170 remeros.

- 13 sailors (να.ται) who were responsible for the manoeuvres (timons/timons), the grove and the sailor, whose function was to execute the orders concerning sailing, although they could also help in the approaches.

- 10 epibates, hoplitas intended to combat during boarding, landing or serving for the protection of the anchoring device; several naval archers were also used to harass the enemy ships before boarding.

- In Hellenistic times, the katapeltaphetai they were responsible for the enlistment and handling of the war machines installed on the ships.

The total crew was approximately 200 men, a considerable figure for a ship. To assemble a fleet of 200 triremes, 40,000 citizens were necessary. This figure can give us the measure of the disaster that the Battle of Aegospotami represented for Athens in 405 BC. C., with the loss of 160 ships, and their crews, captured or executed.

In any case, the number of men on board was not fixed and varied over the years depending on the number of epibats embarked.

The epibats

This infantry was very numerous in the first years of the V century BC. C., when the attack with the ram had not yet become a standard in naval combat. Thus, for example during the Persian Wars, in 494 BC. C. during the naval Battle of Lade: "those from Chios had contributed one hundred ships, on board each of which there were forty elite soldiers recruited from the citizens"

Some years later, the ships that fought the Battle of Salamis carried 30 infantry, while the Athenian ships each had 14 hoplites and 4 archers (toxótai). The archers did not go with the epibats on deck, but stood next to the captain and helmsman, and were their personal guard, as described in an inscription from 412-411 BC. C. Euripides names them in Iphigenia among the taurus , located at the stern, covering the captain and the helmsman during combat.

In May 431 BC. C., a fleet of 100 Athenian triremes embarked 10 hoplites and 4 archers each, their commanders being Carcinus the Elder, Proteas and Socrates. Dart throwers (akonistaí) could also be added to these soldiers; But the later general rule, even if it may have varied, was that the Athenian triremes were lightened by combatants and reduced to 10 epibats (epibátai) at the time of the Peloponnesian War, a figure adopted by the whole of Greece: «the Lacedaemonians and their allies sent an expedition of one hundred ships against the island of Zacynthus, which is located opposite Elis […]. There were a thousand Lacedaemonian hoplites on board and, as a Navarcan, the Spartiate Cnemus.

The ten Athenian epibats had the highest rank after the captain. In the Decree of Themistocles they are mentioned second. When the fleets clashed, a kind of land battle took place at sea.

Like the rowers of the census class of the most modest citizens, that is, the tetes, the epibats did not pay for their hoplite equipment, which was supplied to them by the polis (city); unlike the Falangites who fought on dry land.

Deck crew

Command of the deck crew (hypēresia) was under the command of the helmsman, the kybernētēs, who was always an experienced sailor and often the commander of the ship.. Veteran sailors could be found in the upper levels of the triremes. Other officers were: the prōreus or prōratēs, officer in charge of operations in the bow, the boatswain (keleustēs), the quartermaster (pentēkontarchos), the riverside carpenter (naupēgos), the flutist (aulētēs), who set the rhythm for the rowers, and two toicharchoi, commanding the rowers on each side.

The rowers

On the highest of the three levels located at the furthest point from the axis of the nave, 31 tranitas (thranítai, from trânoι= stools) sat on stools. on each gunwale, seated 89 cm (two cubits) from each other, and slightly in front of and above the corresponding zigita. So that their oars did not interfere with those on the lower levels, they were installed in a device elevated above the hull and open to the wind. The paddles for their oars rested on flying buttresses that protruded about a meter from each side of the trireme. The stroke of their oars was the most energetic, because they pivoted from very high, entering the water first. In the middle row and inside the hull, on the beams, there were 27 rowers, called "zigites" (zygioi, from zeugon, bao), slightly displaced in relation to their upper neighbors, to make better use of the vertical space and to pass their oars through an openwork place in the hull. Each zigite sat above and slightly in front of the corresponding thalamite, and rested his oar on the gunwale. On the lower level, in the hold, 27 "thalamites" (thalamitoi, from thálamos= hold), also displaced for the same reasons, operated their oars through the ports, circular openings located about 45 cm from the waterline. A small leather wrapper was carefully adapted around the oar, to facilitate its penetration and prevent water from getting it wet. If there was a risk of damage to the oars, they were raised and the openings were covered with the ports.

As the hull curved and lengthened at each end, the lower banks were compressed. Consequently there were four extra trains.

In Athens in the V century BC. C., and while the city was able to provide the labor, (that is, until the second phase of the Peloponnesian War) all the rowers were free citizens, eventually reinforced by metics and paid with a salary equivalent to that of the land troops. This salary consisted of a daily drachma at the time of the expedition to Sicily, to which was added, for this specific operation, an extraordinary payment only to the Tranites, which was disbursed by the trierarchs. This special compensation was due to the fact that their work, their superior category and, on this occasion, their better pay, required more effort, since they handled the longer oars. They were recruited from among the most skilled rowers, and were more exposed to the enemy in naval battles.

At least in theory, the State was responsible for the payments, but this represented a more than considerable financial burden, so in practice it was common for the trierarch to make it effective or procured through looting and war booty. It is also assumed that the “specialists” must have received some type of bonus since these were jobs that required qualification. The possibility of receiving a drachma a day was attractive enough that there was no shortage of volunteers from the lower classes (according to the Solonian classification): the tetes. Lacking opportunities to prosper in Attica, the prospect of being enlisted in active service was not at all daunting. And in the event that the citizens of Attica were not enough to cover the rowing banks in their entirety, it is assumed that there would be no problem in recruiting mercenaries from other polis, enlisting metics from one's own Athens or even the slaves.

As for the distribution of rowing benches, there has been controversy for centuries on this issue. The problem has basically consisted of the fact that the literary sources, which mention the trireme countless times, do not stop to describe what it was like, since for them a trireme was something very familiar, known to everyone. As if that were not enough, it has also been shown that there is no continuity between the art of building warships in Antiquity and that of the Modern Age, which we do have well documented. There has been endless debate about what these boats were like: the only thing that seemed to be out of the question is that the rowers were grouped in groups of three (trieres) on each side, but it was not known how they were. exactly. The possible combinations are practically endless, but by knowing exactly the measurements of the ship and reviewing the iconography, together with a new interpretation of the available texts, it has been possible to reach certain conclusions. A hypothesis has been formulated that advocates the existence of two row levels, each with three rows of rowers from bow to stern.

Orthodox theory states that a trireme had three overlapping rows of oars per side, with the banks arranged in a staggered manner. This arrangement, with individual oars, allows them to not be excessively long, and prevents the rowers from getting in each other's way, in the same way that it makes it possible to retract the oars into the interior of the hull in the event of a collision. The Thalamites and Zigites were inside the hull, while the Tranites sat on the overhang of the upper deck. Being in the highest position, the latter were the ones that made the most effort, since when the oar enters the water at a more vertical angle, the lever arm requires more force to be applied. In the same way, the tranites controlled that the rhythm and angle of entry of the oars of their companions was adequate, since the tranites were the only ones who could look out of the ship.

When a trireme entered into combat, it lowered and stowed the small sail (akateion), and was propelled by force of arms. The rest of the time he used to sail.

Likewise, it was possible to face the ship using the oars, reversing the direction of travel with the rowers on one side, so that the ship rotated on itself. Of course, you could also navigate in reverse. The maneuverability of a trireme was truly impressive, capable of making a 180° turn in a distance equivalent to twice the length, and special emphasis was placed on training the rowers to take advantage of it.

The abilities and skills of the rowers in a fleet varied greatly. Sometimes, the best were selected to create an elite flotilla, with which they could achieve greater speed than normal. In this regard, Xenophon says that "Conon was able to flee with the triremes at good speed, because he had gathered the best oarsmen of many crews into a few." Given his great experience, it is likely that many of these oarsmen were aged from thirty to forty years. In Athens, at least, this was the case for veterans of many campaigns when the Peloponnesian War broke out (431 BC).

The condition of the rowers on board

The trireme was small because the space in which there had to be room for three levels of rowers on their benches was subject to the height of the ship (about 2.15 m) and the short distance between any two rowers. It was particularly uncomfortable during a "long day rowing" voyage, about 16 hours.

The two upper levels were exposed to the wind like the portals of the thalamites, arranged near the surface. Thus, when the sea was rough, the waves that hit the sides of the ship wet the sailors and penetrated inside, where they accumulated in the bilge, at the bottom of the hold, and the ship became heavy.

The Athenian general Cabrias is credited with discovering the solution to remedy these problems:

Cabrias stretched skins without curling against the waves on one and the other side of the bow and, firmly clutching them at the top of the bridge, picked them up as a parapet for the bow. This prevented the ship from falling water while it was advancing and the sailors were soaked by the waves, because by not seeing the waves that were thrown on them, thanks to the protection of the parapet, fear did not lift them up, and thus prevented the ship from breaking.Polyene, Stratagems III.11.13

In the Athenian navy, triremes were classified by categories, according to their state of maintenance and age. Another distinction established whether the triere was “aphracto” or “cataphracto”. Using a mobile system, the triremes could be equipped with fixed and rigid panels that offered better protection against the attacks of the sea and enemy arrows. These ships were called cataphractas, as opposed to the aphracta galleys that did not have these protections. Protection that generally consisted of a type of leather or canvas tent. The tarps (called pararrŷmata) protected the Tranites from attacks with arrows or javelins. In the Battle of Aegospotamos (405 BC), "Lysander, at dawn, gave the order to board the ships after breakfast, and made all the arrangements for combat, even extending the protection for arrows."

The adjectives aphract and cataphract have a second meaning: —φραχτος— derived from φράττεσθαι (ναῦν) "manipulating a ship", for example by enhancing the gunwale with wicker mats, reed mats, etc. The trireme equipped with flying falcas It was called πεφραγμένη ναῦς. From a certain point on, the triremes wore these protections permanently, definitively closing the space that separated the outer edge of the apostis from the combat bridge with the fixed falcas (wooden panels or additional planks that covered the openings). Such trieres were called χατάραχτοι: with "fixed falcas" (or permanent). In the opposite case they were ἆφραχτοι: "without falcas". The trireme in the Lenormant relief is affront since the Tranite oarsmen are visible.

Apart from the basic design there were a series of variants, which usually came from the transformation of older ships: fast transport ships to carry horses and soldiers, in which the banks of thalamites and zigites were removed to make room for load.

In the rest of the Greek navies, the design of the triremes presented some differences. The Peloponnesians trusted in the higher quality of their epibats, so they incorporated a greater number of them into their complement and tried to combat the boarding. For this reason, their triremes were of more solid construction, heavier and slower, prepared to resist the onslaught of the enemy trireme as a preliminary step to hand-to-hand combat.

Social impact

The growing role of the Tetes social class in military affairs during the V century BC. C., was not exempt from causing commotions in the city's politics, mainly in Athens, where these men were the essential instrument of their successes at sea: the Tetes saw their social role grow, just as a century before with the Zeugites who had to equip themselves as hoplites at their own expense, and became decisive ground units.

Tactics

Although until the VI century BC. C., naval battles were mainly limited to a boarding maneuver and an infantry combat on one ship or the other. From that date and thanks to the maneuverability of the trireme, the use of the ram was imposed. The frontal attack by enemy ships could damage the structures of the parexeiresia and destroy some tranites, without the waterline being permanently affected.

Similar to what was done with the hoplite phalanx on land, combat at sea was done in line. Athens, to maximize the benefits offered by this vessel, developed new tactics based on an original arrangement of the fleet aligned in columns, a tactic already known but little exploited.

During combat preparation, the rig was deposited on the ground because it was useless for maneuvers, which were carried out solely by using the oars. The trireme had to be able to turn in any direction and could not depend on the winds.

All the naval tactics developed in this era derive from the pursued objective: the attack with the ram. The tactical naval tactics of the centuries V and IV a. C. are well known thanks to two passages from Thucydides: the harangue of the Athenian Phormio before the Battle of Naupactus (September 429 BC), and the reasoning of the Syracusans who taught the Athenians a lesson in the Battle of Erineus (spring of 413 BC). The Athenians practiced a war of movement that demanded a large free space (the famous εὐρυϰωρία) and crews experienced in maneuvers. The most common tactics in combat were:

- the diekplous (Ancient Greek δικπλους: "navigation through"), in which it was sought to create a hole in the adverse line and then attack for its rearguard. It was the master tactic of these fighting.

- The trirremes were arranged in columns, usually two, and launched through the enemy fleet ordered online. At the time of passing by a ship the oars were quickly reintroduced into the inside of the hull, which destroyed those of the enemy, damage to which the sailors suffered on the benches were added. Once the adverse line was immobilized and overwhelmed, the Athenians could easily carry out their maneuvering with the spur. Perhaps this tactic was devised by the Phoenicians or Carthaginians; for so says Sosilo the Lacedony, in the account of a naval battle won by the Romans, in the course of the second Punic War (it can be about the victory in 217 B.C. of Cneo Cornelio Escipion Calvo in the mouth of the River Ebro. (Cf. Ulrich Wilcken, Hermes, XLI, 1906, pp. 103-141):

All the ships [of the Roman side] made prowess in combat, particularly the masliots. They had been the first to engage in battle, provoking themselves in spirits and support, praising their allies, and personally apprehended the enemies with an unparalleled resolution. Double was the defeat of the Carthaginians, because the masliots distrusted their own tactics (from the Carthaginians). When the Phoenicians (?) faced ships ordained in line of front, they had the habit of replenishing against the enemy as if they were to sprinkle at once, they crossed their line, but instead of sprinkling it, they saw and then they were thrown upon the enemy ships just at the time when they were presented in oblique position (διεκπλεικεικικικικικικεικικικικικικικικικικικικεικικικικικικεικικικεικικικικικικικικικικικικικικικικικικικικεικικικικικικικικικικικικεικικικικικικικεικικικικικικικικικικικικε Knowing for tradition the battle that Artemisio had waged, as it is said, Heráclides de Milasa (a man whose intelligence stood out over that of his contemporaries), the Masoliotas ordered the first line of their ships and gave the order to leave behind, and at well calculated intervals, other reserve ships. From the fact that the Carthaginians failed the first line, these reserve ships, without having moved from the assigned site, had to attack the enemy ships in the favorable moment, when they passed by presenting the flank.

- Sosilo does not describe only the diekplous, but also one of the three ways to stop it. This stop consisted of aligning their ships on two front lines, each boat on the second line was behind a ship of the first. This seems to be the device adopted by Conón and Farnabazo II against Spartans in Cnido (summer 394 BC).

- This tactic proved so effective that three centuries after its development, Polibio continued to consider it the best (πσακτικετατατον):

The imperfection of the Roman dots and the heaviness of their ships made impossible something that provides great successes in the naval battles: to sail between the enemy ships and to go back against those who fight against their own formation.Polibio, Stories I.51.9-10

- This tactic was already known at least by the firemen at the end of the centuryVIa. C., although little was practiced due to the original disposition of the fleet and the lack of training of sailors.

- You could also align the ships on two front lines, but forming a five-year: the ships of the second line closed the step to the diekplous. It was the Athenian tactic in the Battle of Arginusas (406 BC).

- the kyklos was a defensive circle used in case of numerical inferiority. It was a desperate solution to confront the diekplous.

- It was intended to prevent the enemy from creating a gap in the squad thanks to the protection sought by the rostrums back out. This tactic was sometimes used in case of technical advantage, due to both the material and the crew's ability. Wrong employee, he could reveal himself disastrous as he was for the Japanese in 429 a. C. in front of Patras, despite being numerically superior to the Athenians. Tucidides tells us:

The Pelopians arranged their ships in a circle, the largest they could form without giving rise to the rupture of the line, with the proas out and the sterns inward, and placed inside the light vessels that accompanied the fleet and five trirremes that were very sailors, so that they could come out in a short time to help any point that attacked the opposites.

The Athenians, lined up one ship after another, began to circle around the Pelopians and were enclosing them in a small space, always going to the roots and giving the impression that they would be thrown into the attack immediately. [...] So the wind began to blow and the ships that were already in a small space, began to mess with the simultaneous action of two causes, the wind and the boats, and to crash some against others [...] then at that very moment, Formion gave the signal.Tucidides, History of the Peloponnesian War II.83.5; 84.1-3

- the periplous (Ancient Greek περπλους) or enveloping consisted of spying on the enemies by the flank or behind.

- It was the maneuver that the Athenians successfully used in the above-mentioned episode. infra. The fleet was arranged in column (/25070/κρως) and made circles that narrowed around the enemy units: the fear, the impossibility of properly serving of the rows if the ships were very close to each other, the whims of the wind or the currents, provoked the disorder, which exploited the attacker. This was the maneuver brilliantly performed by Formion at the Battle of Rio (August 429 BC): with 20 trirremes deshizo 47 platoons.

- A variant aimed at attacking an online detached fleet was to overwhelm the wings in order to catch the enemy for the rear, a tactic similar to the target sought in a land combat.

The success of these maneuvers depended mainly on the quality and good work of the rowers: if they were experts they could attack faster, as well as make sudden changes in direction and acceleration to spur. In the second part of the Peloponnesian War, when Athens could no longer support the war effort and was forced to use foreigners, including prisoners of war, to arm its ships, the effectiveness of its fleet declined and it could not do against the enemy's forces. During the expedition to Sicily, Nicias had Athens brought to Athens in 414 BC. C. a message requesting help, which is revealing of the state of the fleet:

And our crews have suffered losses and still suffer them for the following. The sailors, when they collect firewood or go for the spoil and water at a great distance, fall into the hands of the cavalry, the slaves since our forces have balanced themselves to the enemy; and as for the foreigners, those who embarked for obligation as soon as they can disperse through the cities, while of those who were at the beginning seduced by a great weld, once they have seen, as much as possible, There are even some who have traded with Hícara slaves and who have persuaded the trier to embark on them instead, thus ending with the efficiency of the fleet.Tucidides, History of the Peloponnesian War VII.13.2

And a little later:

How few are the sailors who, once the ship has moved, manage to maintain the cadence of the masters.Tucidides, History of the Peloponnesian War VII.14.1-2

These passages illustrate the profound disorganization that reigned within the Athenian crews during the last years of the conflict, increased by the serious technical problems of maintaining the triremes in good condition.

Strategies

The crews lost sight of the coast as little as possible, because the trireme was, in short, an unsafe vessel: at the slightest gust of wind it had to seek shelter on the coast. Furthermore, although fast and light, she was incapable of being at sea for a long time without care. To caulk it, to preserve it, it was necessary for it to touch the ground frequently. On board there was an extraordinary overcrowding of men and material: provisions could not be shipped for a long time; on the other hand, as a result of the overcrowding, the crew could only really rest on land, and spent the nights, as late as possible. often possible, on the shore. Eating and sleeping on board negatively affected the crews.

The need to maintain contact with the ground had major drawbacks:

- increased the risk of loss by shipwreck. In 480 B.C., just after the Battle of Artemisio, a Persian division that contoured Eubea was surprised, pushed to the coast and completely destroyed by a storm.

- prevented the maritime blockade. When in the winter of the year 430-429 B.C., Formion wanted to block the Gulf of Corinth, it could not dispose of its triremes in the high seas. He "buried himself" in Naupacto, and from the port he watched the strait of Corinth. For the same reason, Athenians could never block Syracuse.

- forced the fleets to rely on numerous bases. It is a fact that the Athenian maritime power was partially founded on the narrow control of the Aegean islands, where the peoples first treated as allies lived, in the Confederation of Delos, and then subjugated, especially during the Peloponnese War.

The Athenian fleet, taking into account its technical possibilities, had three fundamental missions to perform:

- the protection of the coasts of the Atica: "the Athenians set up ground and sea surveillance stations in areas that wanted to be monitored throughout the war [of the Peloponnese]". These measures, however, did not contemplate the protection by sea of El Pireo. Instead, they assured the garrisons of the forts that protected the Atica, such as Enoe, Oropo and Panacto, and those of strategic points such as the fort of Búdoro, located in the northwest tip of the island of Salamina, whose mission and of the three trirremes there destined, was to monitor the entry of the Saronic Gulf. (cf. Tucídides II.93.4) and Naupacto (Tucídides II.69.1).

- the destruction of the enemy naval forces that must assure the Athenians the dominion of the sea.

- the attack of the enemy coasts: it was "to disembark some times on one point and others on another of the enemy country and to subject it to pillage". It was usually operated by surprise and with minimal costs. Regarding the epibates "[Conón] made them disembark at sunset so that they would not be seen by the enemies." The epibates, which constituted disembarkation companies that devastated the territory, never went too far. The episode of Micaleso (413 B.C.) gives an idea, indirectly, of the limits of his incursions: Diítrefes, at the head of the betrayal mercenaries, easily took over Micaleso, because "it fell on an unprepared population and did not expect at all that an enemy would enter so far from the sea to attack it." Now, from Calcis to Micaleso there are 13.6 km along the route that crosses a mountain port and, from the Gulf of Áulide to Micaleso, there are 7 km to bird's flight.