Treblinka extermination camp

Treblinka was an extermination camp built and operated by Nazi Germany in occupied Poland during World War II. It was located in a forest northeast of Warsaw, 4 kilometers south from the Treblinka train station, in what is now the Masovian Voivodeship. The camp operated between July 23, 1942 and October 19, 1943 as part of Operation Reinhard, the deadliest phase of the Final Solution. During this time, an estimated 700,000 to 900,000 Jews were murdered. in its gas chambers, along with 2,000 Roma. More Jews were murdered in Treblinka than in any other Nazi death camp apart from Auschwitz.

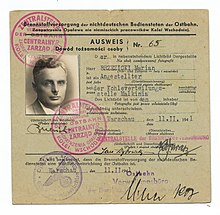

Runned by German SS and Trawniki guards, voluntarily enlisted among Soviet POWs to serve with the Germans, the camp consisted of two separate units. Treblinka I was a forced labor camp (Arbeitslager ) whose prisoners worked in the gravel pit or irrigation area and in the forest, where they cut firewood to feed the cremation pits. Between 1941 and 1944, more than half of its 20,000 inmates died by execution summaries, hunger, disease and mistreatment.

The second camp, Treblinka II, was an extermination camp (Vernichtungslager), euphemistically referred to as the SS-Sonderkommando Treblinka by the Nazis. A small number of Jewish men who were not killed immediately upon arrival became their Jewish slave labor units called Sonderkommandos, forced to bury the bodies of the victims in mass graves. These corpses were exhumed in 1943 and cremated in large open-air pyres along with the bodies of the new victims. The gassing operations at Treblinka II ended in October 1943 after a revolt by the Sonderkommandos in early august. Several Trawniki guards were killed and 200 prisoners escaped from the camp; almost a hundred survived the subsequent pursuit. The camp was dismantled before the Soviet advance. A watchman's farmhouse was built on the site and the ground was plowed in an attempt to hide evidence of genocide.

In postwar Poland, the government bought most of the land where the death camp was located, and built a large stone monument there between 1959 and 1962. In 1964, Treblinka was declared a national martyrdom monument Jew at a ceremony at the site of the former gas chambers. In the same year the first German trials for war crimes committed at Treblinka by former SS members were held. After the end of communism in Poland in 1989, the number of visitors coming to Treblinka from abroad increased. An exhibition center was opened in the camp in 2006. Later it was expanded and became a branch of the Siedlce Regional Museum.

Historical context

Following the invasion of Poland in 1939, most of Poland's 3.5 million Jews were rounded up and placed in newly established ghettos by Nazi Germany. The system was intended to isolate Jews from the outside world to facilitate their exploitation and abuse. The food supply was inadequate, living conditions poor and unsanitary, and Jews had no way of earning money. Malnutrition and lack of medication led to high mortality rates. In 1941, the Wehrmacht's initial victories over the Soviet Union inspired plans for German colonization of occupied Poland, including all territory within the new General Government district.. At the Wannsee Conference near Berlin on January 20, 1942, new plans were drawn up for the genocide of the Jews, known as the "Final Solution" to the Jewish question. The extermination program was codenamed the Aktion Reinhard in German, to differentiate it from the mass murder operations of the Einsatzgruppen in territories conquered by Nazi Germany, in which half a million people had already been annihilated. Jews.

Treblinka was one of three secret death camps established for Operation Reinhard; the other two were Bełżec and Sobibór. All three were equipped with gas chambers disguised as showers, for the "processing" of entire transports of people. The killing method was established after a pilot project of mobile extermination carried out in Soldau and at the Chełmno extermination camp which began operations in 1941 and used gas vans. Chełmno (German: Kulmhof) was a testing ground for the establishment of faster methods of killing and cremating people. It was not part of Reinhard, which was marked by the construction of stationary assassination facilities mass killings. Treblinka was the third Operation Reinhard death camp to be built, following Bełżec and Sobibór, and incorporated lessons learned from its construction. Alongside the Reinhard camps, mass killing facilities were developed with Zyklon B at the Majdanek concentration camp in March 1942 and at Auschwitz II-Birkenau between March and June.

Nazi plans to kill Polish Jews from the entire General Government during Aktion Reinhard were overseen in occupied Poland by SS-Gruppenführer Odilo Globocnik, delegate of the Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler in Berlin. Operation Reinhard camps reported directly to Himmler. Operation Reinhard personnel, most of whom had been involved in the euthanasia program Aktion T4, used T4 as a framework for the construction of new facilities. Most of the Jews who were murdered in Reinhard's camps came from ghettos.

Location

The two parallel Treblinka fields were built 80 kilometers northeast of the Polish capital, Warsaw. Before World War II, it was the location of a gravel mining company for the production of concrete, connected to the most major cities in central Poland via the Małkinia–Sokołów Podlaski railway junction and Treblinka village station. The mine was owned and operated by Polish industrialist Marian Łopuszyński, who added the new 6 kilometer railway to the existing line. When the German SS took over Treblinka I, the quarry was already equipped with heavy machinery that was out of the box. Treblinka was well connected but isolated enough, halfway between some of the largest Jewish ghettos in Nazi-occupied Europe, including the Warsaw Ghetto and the Białystok Ghetto, the capital of the newly formed Bezirk Bialystok. The Warsaw ghetto had 500,000 Jewish inmates and the Białystok ghetto had around 60,000.

Treblinka was divided into two separate camps that were 2 kilometers apart. Two engineering companies, Leipzig's Schönbronn and the Warsaw branch of Schmidt–Münstermann, supervised the construction of both camps. Between 1942 and 1943, the killing center was further redeveloped with a crawler excavator. New gas chambers made of brick and concrete were recently erected, and mass cremation pits were also introduced. The perimeter was widened to provide a buffer zone, making it impossible to approach the camp from the outside. The number of trains caused panic among the residents of the nearby settlements. They would probably have been killed if they had been caught near the railway tracks.

Treblinka II

Opened on September 1, 1941 as a forced labor camp (Arbeitslager), Treblinka I replaced an ad hoc company created in June 1941 by the Sturmbannführer Ernst Gramss. A new barracks and 2 meter high barbed wire fence were erected in late 1941. To obtain the workforce for Treblinka I, civilians were sent to the countryside en masse for real or imagined crimes, and the office of the Gestapo in Sokołów, which was headed by Gramss. The average length of a sentence was six months, but many prisoners had their sentences extended indefinitely. Twenty thousand people passed through Treblinka I during its three years of existence. About half of them died there from exhaustion, starvation, and disease. Those who survived were released after serving their sentences; they were usually Poles from nearby villages.

At any given time, Treblinka I had a workforce of 1,000 to 2,000 prisoners, most of whom worked 12- to 14-hour shifts in the large quarry and then also extracted wood from the nearby forest for fuel for the open-air crematoria in Treblinka II. Among them were German, Czech and French Jews, as well as Poles captured in łapankas, farmers unable to deliver the requested amounts of food, hostages caught by chance and people who attempted to harbor Jews outside of Jewish ghettos or who performed restricted actions without permission. Beginning in July 1942, Jews and non-Jews were separated. The women mainly worked in the sorting barracks, where they repaired and cleaned military clothing delivered by freight trains, while most of the men worked in the gravel quarry. There were no work uniforms, and inmates who lost their own shoes were forced to go barefoot or collect them from dead prisoners. Water was rationed, and punishments were applied regularly at roll call. As of December 1943, inmates no longer had specific sentences. The camp officially functioned until July 23, 1944, when the imminent arrival of Soviet forces led to its abandonment.

Throughout its operation, the commander of Treblinka I was Sturmbannführer Theodor van Eupen. He led the camp with several SS men and almost 100 Hiwi guards. The quarry, spread over an area of 17 hectares, supplied road construction material for German military use and was part of the strategic road construction program in the war with the Soviet Union. It was equipped with a mechanical excavator for shared use by Treblinka I and II. Eupen worked closely with SS commanders and German police in Warsaw during the deportation of Jews in early 1943 and prisoners from the Warsaw Ghetto were brought to him for necessary replacements. According to Franciszek Ząbecki, the head of the local station, Eupen used to kill prisoners by "shooting them, like partridges". One much feared foreman was Untersturmführer Franz Schwarz, who executed prisoners with a pick or hammer.

Treblinka II

Treblinka II (officially SS-Sonderkommando Treblinka) was divided into three parts: Camp 1 was the administrative complex where the guards lived, Camp 2 was the reception area where transports were unloaded incoming prisoners and Camp 3 was the location of the gas chambers. All three parts were built by two groups of German Jews recently expelled from Berlin and Hanover and imprisoned in the Warsaw Ghetto (a total of 238 men aged 17 to 35 years old). The Hauptsturmführer Richard Thomalla, head of construction, brought German Jews because they could speak German. Construction began on April 10, 1942, when Bełżec and Sobibór were already in operation. The entire death camp, which was 17 hectares or 13.5 hectares (sources vary), was surrounded by two rows of barbed wire fences 2.5 meters high. This fence was later covered with pine branches to obstruct the view of the field. More Jews were brought in from the surrounding settlements to work on the new rail ramp within the Camp 2 reception area, which was ready by June 1942.

The first section of Treblinka II (camp 1), which was the administrative and residential complex of Wohnlager; I had a phone line. The main road within the camp was paved and named Seidel Straße after Unterscharführer Kurt Seidel, the SS corporal who supervised its construction. Some side roads were lined with gravel. The main gate for road traffic was erected on the north side. The barracks were built with supplies delivered from Warsaw, Sokołów Podlaski and Kosów Lacki. There was a kitchen, a bakery, and dining rooms; all were furnished with high-quality items taken from Jewish ghettos. The Germans and Ukrainians each had their own bedrooms, angled for better control of all entrances. There were also two barracks behind an inner fence for Jewish labor commandos. SS-Untersturmführer Kurt Franz established a small zoo in the center next to his horse stables, with two foxes, two peacocks and a roe deer (brought in 1943). Smaller rooms were built that served as laundry, workshops for tailors and shoemakers, and for carpentry and medical assistance. Closer to the SS quarters there were separate barracks for Polish and Ukrainian service, cleaning and cooking women.

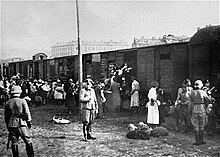

The next section of Treblinka II (camp 2, also called the lower camp or Auffanglager), was the reception area where the railway unloading ramp extended from the Treblinka line into the camp. There was a long narrow platform surrounded by barbed wire fencing. A new building, erected on the platform, was disguised as a railway station complete with a wooden clock and fake railway terminal signs. The SS-Scharführer Josef Hirtreiter who worked on the unloading ramp was known to be especially cruel; he grabbed the crying little children by their feet and smashed their heads against the carriages. Behind a second fence, about 100 meters from the track, were two large barracks used for undressing, with a cashier's booth that collected money and jewelry, apparently for safekeeping. Resisting Jews were led away or beaten to death by guards. The area where the women and children were stripped of their hair was across the way from the men. All the buildings in the lower camp, including the barber's barracks, contained the stacked clothes and belongings of the prisoners. Behind the station building, further to the right, was a sorting square where the Lumpenkommando collected all the luggage. It was flanked by a fake infirmary called "Lazaret" with the sign of the Red Cross. It was a small barracks surrounded by barbed wire where sick, old, injured and "difficult" they were locked up. Directly behind the "Lazaret" cabin was a ditch seven meters deep. Blockführer Willi Mentz, nicknamed "Frankenstein" by the prisoners, led these prisoners to the edge of the ditch and shot them one by one. Mentz single-handedly executed thousands of Jews, with the help from his supervisor, August Miete, who was called the "Angel of Death" by the prisoners. The ditch was also used to burn old worn-out clothing and identity documents deposited by new arrivals in the undressing area.

The third section of Treblinka II (Camp 3, also called Upper Camp) was the main killing area with gas chambers at its center. It was completely protected from the railway tracks by an earth bank built with the help of of a mechanical excavator. This mound was elongated in shape, similar to a retaining wall, and can be seen in a sketch produced during the 1967 trial of Treblinka II commander Franz Stangl. On the other sides, the area was camouflaged from the new arrivals like the rest of the camp, using tree branches introduced between barbed wire fences by the Tarnungskommando (the detail of the work led to their collection). From the bare barracks there was a fenced path through the wooded area to the gas chambers. It was cynically called die Himmelstraße ("the street to heaven") or der Schlauch ("the tube") by the SS. During the first eight months of the camp's operation, the bulldozer was used to dig burial trenches on either side of the gas chambers; these trenches were 50 meters long, 25 meters wide and 10 meters deep. In early 1943 they were replaced by cremation pyres up to 30 meters long, with rails set over the pits in concrete blocks. The 300 prisoners who operated the upper camp lived in separate barracks behind the gas chambers.

Process of the massacre

Unlike other Nazi concentration camps in German-occupied Europe, in which prisoners were used as forced laborers for the German war effort, death camps (Vernichtungslager) like Treblinka, Bełżec and Sobibór had only one function: to kill the envoys there. To prevent incoming victims from realizing its nature, Treblinka II was disguised as a transit camp for deportations further east, complete with fictitious train schedules, a fake train station clock with painted needles, destination names, fake ticket booths and the sign "Ober Majdan", a code word for Treblinka that was commonly used to fool prisoners arriving from Western Europe. Majdan was a pre-war farm 5 kilometers from the camp.

Polish Jews

The mass deportation of Jews from the Warsaw ghetto began on July 22, 1942, with the first shipment of 6,000 people. The gas chambers began operating the next morning. For the next two months, deportations from Warsaw continued daily via two shuttle trains (the second, from 6 August 1942), each with between 4,000 and 7,000 people crying for water. No other trains were allowed to stop at Treblinka station. The first daily trains arrived early in the morning, often after an overnight wait, and the second, in mid-afternoon. All new arrivals were sent immediately to the undressing area by the Sonderkommando squad manning the arrival platform, and from there to the gas chambers. According to German records, including the official report of SS-Brigadeführer Jürgen Stroop, 265,000 Jews were transported by freight trains from the Warsaw Ghetto to Treblinka during the period from July 22 to September 12. from 1942.

Traffic on the Polish railway lines was extremely heavy. An average of 420 German military trains ran over internal traffic every 24 hours as early as 1941. Holocaust trains were routinely delayed en route; some transports took many days to arrive. Hundreds of prisoners died of exhaustion, suffocation and thirst while in transit to the camp in the overcrowded wagons. In extreme cases such as the Biała Podlaska transport of 6,000 Jews traveling alone to a distance of 125 kilometers, up to 90 percent of the people were already dead when the sealed doors were opened. Beginning in September 1942, Polish and foreign Jews were greeted with a brief verbal announcement. An earlier sign with instructions was removed as it was clearly insufficient. Deportees were told they had arrived at a transit point en route to Ukraine and needed to shower and disinfect their clothing before receiving work uniforms and new orders.

Foreign Jews and Gypsies

Treblinka received transports of almost 20,000 foreign Jews between October 1942 and March 1943, including 8,000 from the German Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia via Theresienstadt, and more than 11,000 from Thrace, Macedonia and Pirot occupied by the Bulgarians following an agreement with the Nazi-allied Bulgarian government. They had train tickets and arrived predominantly in passenger carriages with considerable luggage, food and travel drinks, all of which were taken by the SS to the food storage barracks. Provisions included items such as smoked lamb, specialty breads, wine, cheese, fruit, tea, coffee, and sweets. Unlike Polish Jews arriving on Holocaust trains from nearby ghettos to cities like Warsaw, Radom and the Bezirk Bialystok, foreign Jews received a warm welcome upon the arrival of an SS man (Otto Stadie or Willy Mätzig), after which they were murdered like the others. Treblinka dealt mainly with Polish Jews, Bełżec handled Jews from Austria and the Sudetenland, and Sobibór was the final destination for Jews from France and the Netherlands. Auschwitz-Birkenau "processed" to Jews from almost every other country in Europe. The frequency of arriving transports decreased in winter.

The uncoupled locomotive returned to the Treblinka station or the laying yard in Małkinia for the next transport, while the victims were taken from the wagons to the platform by the Kommando Blau, one from detachments of Jewish forced laborers forced to help the Germans in the camp. They were herded through the gate amidst chaos and shouting. They were separated by gender behind the gate; the women were pushed into the barracks to undress on the left and the men were sent to the right. They were all ordered to tie their shoes and undress. Some kept their own towels. The Jews who resisted were taken to the "Lazaret", also called the "Red Cross infirmary", and shot behind it. The women had their hair cut; therefore, it took longer to prepare them for the gas chambers than men. The hair was used in the manufacture of socks for submarine crews and felt shoes for the Deutsche Reichsbahn.

Most of those killed at Treblinka were Jews, but around 2,000 Gypsies also died there. Like the Jews, the Roma were first rounded up and sent to the ghettos; at a conference on January 30, 1940 it was decided that the 30,000 Roma living in Germany should be deported to the former Polish territory. Most of these were sent to Jewish ghettos in the General Government, such as those in Warsaw and Łódź. As with the Jews, most of the Roma who went to Treblinka died in the gas chambers, although some were shot. Most of the Jews living in ghettos were sent to Bełżec, Sobibór or Treblinka to be executed; most of the gypsies living in the ghettos were shot on the spot. There are no known Roma escapees or survivors from Treblinka.

Gas chambers

After undressing, newly arrived Jews were beaten with whips to lead them to the gas chambers; hesitant men were treated particularly brutally. Rudolf Höss, the Auschwitz commandant, compared the practice at Treblinka of misleading victims about showers to his own camp's practice of telling them they had to go through a 'disappearance' process. According to In the postwar testimony of some SS officers, the men were always gassed first, while the women and children waited their turn outside the gas chambers. During this time, women and children could hear the sound of suffering within the chambers and realize what was in store for them, causing panic, anguish, and even involuntary defecation.

Many survivors of the Treblinka camp testified that an officer known as "Ivan the Terrible" was responsible for operating the gas chambers in 1942 and 1943. As Jews awaited their fate outside the gas chambers, Ivan the Terrible allegedly he tortured, beat and murdered many of them. Survivors witnessed Ivan hit people's heads with a pipe, cut people's flesh with a sword or bayonet, cut off their noses and ears, and gouge out their eyes. One survivor testified that Ivan killed a baby. slamming him against a wall; and another claimed that he raped a young woman before ripping open her abdomen and leaving her to bleed to death.

The gassing area was completely enclosed with a tall wooden fence made of vertical boards. Originally, it consisted of three interconnected barracks 8 meters long and 4 meters wide, disguised as showers. They had double walls insulated by compacted earth in between. The interior walls and ceilings were covered with wallpaper. The floors were covered with tinned sheet metal, the same material used for the roof. The solid wooden doors were insulated with rubber and blocked from the outside by heavy cross bars.

According to Stangl, a rail transport of about 3,000 people could "be processed" in three hours. In a 14-hour workday, between 12,000 and 15,000 people were murdered. After the new gas chambers were built, the duration of the killing process was reduced to an hour and a half. Victims were gassed to death. death by exhaust gases led through pipes from a Red Army tank engine. SS-Scharführer Erich Fuchs had it installed. The SS brought the engine in the at the time of the camp's construction and housed in a room with a generator that supplied electricity to the camp. The exhaust pipe from the tank engine ran just below the ground and opened into the three gas chambers. The fumes could be see coming out After about 20 minutes, the bodies were removed by dozens of Sonderkommandos, placed on carts and removed. The system was imperfect and required a lot of effort; late-arriving trains had to wait on the stopping tracks overnight at Treblinka, Małkinia or Wólka Okrąglik.

Between August and September 1942, a large new building with a concrete base was constructed from bricks and mortar, under the guidance of Action T4 euthanasia expert Erwin Lambert. It contained 8-10 gas chambers, each 8 meters by 4 meters, and had a corridor in the center. Stangl oversaw its construction and brought building materials from the nearby town of Małkinia having exhausted the factory's stock. During this time, victims continued to arrive daily and were led naked past the construction site to the original gas chambers. The new gas chambers became operational after five weeks of construction, equipped with two engines (instead of one) that produced smoke. The metal doors, which had been dismantled from Soviet military bunkers around Białystok, they had portholes through which it was possible to view the dead before removing them. Stangl said that the old death chambers were capable of killing 3,000 people in three hours. The new ones had the "exit" highest possible height of the gas chambers in the three Operation Reinhard death camps and could kill as many as 22,000 or 25,000 people every day, a fact Globocnik once boasted to Kurt Gerstein, a fellow SS officer. of the Disinfection Services. The new gas chambers were rarely used to their full capacity; the daily average was between 12,000 to 15,000 victims.

The extermination process at Treblinka differed significantly from the method used at Auschwitz and Majdanek, where the pesticide Zyklon B (hydrogen cyanide) was used. In Treblinka, Sobibór and Bełżec, victims died from suffocation and carbon monoxide poisoning from engine exhaust in stationary gas chambers. In Chełmno, they were transported inside two specially designed and equipped trucks, driven at a speed scientifically calculated to kill the Jews inside during the journey, instead of forcing the drivers and guards to kill at the destination. After visiting Treblinka on a guided tour, Auschwitz commandant Rudolf Höss concluded that the use of exhaust gases was inferior to the cyanide used in his death camp. The chambers went silent after 12 minutes and were closed for 20 minutes or less. According to Jankiel Wiernik, who survived the 1943 prisoner uprising and escaped, when the doors to the gas chambers opened, the bodies of the dead were standing and kneeling rather than lying down, due to severe overcrowding. Dead mothers hugging the bodies of their children. Prisoners working at Sonderkommandos later testified that the dead used to let out a last breath of air when they were led out of the chambers. Some victims showed signs of life during the removal of the corpses, but the guards routinely refused to react.

Cremation Pits

The Germans realized the political danger associated with the mass burial of corpses in April 1943, when they discovered the graves of Polish victims of the Katyn massacre, carried out by the Soviets near Smolensk in 1940. The bodies of the 10,000 Polish officers executed by the NKVD were well preserved despite their long burial. The Germans formed the Katyn Commission to prove that the Soviets were solely responsible, and used radio transmissions and film to alert the Allies. about this war crime. Subsequently, the Nazi leadership, concerned with covering up its own crimes, issued secret orders to exhume the bodies buried in the death camps and burn them. The cremations began shortly after Himmler's visit to the camp in late February or early March 1943.

To cremate corpses, large cremation pits were built at Camp 3 within Treblinka II. The burning pyres were used to cremate the new corpses along with the old ones, which had to be dug up as they were buried during the first few years. six months of camp operation. Built under the instructions of Herbert Floß, the camp's cremation expert, the pits consisted of railroad tracks set like railings on concrete blocks. The corpses were placed on rails over wood, splashed with gasoline and burned. It was a heartbreaking sight, according to Jankiel Wiernik, with the bellies of pregnant women exploding from boiling amniotic fluid. He wrote that "the heat radiating from the pits was maddening". The corpses burned for five hours, without the ash of the bones. The pyres operated 24 hours a day. Once the system was perfected, between 10,000 and 12,000 bodies could be cremated at a time.

Open-air incineration pits were located to the east of the new gas chambers and refueled from 04:00 (or after 05:00, depending on workload) to 18: 00 at approximately 5 hour intervals. The current camp memorial includes a tombstone resembling one of them. It is built of cast basalt and has a concrete base. It is a symbolic grave, as the Nazis scattered real human ashes, mixed with sand, over an area of 2.2 hectares.

Camp organization

The camp was operated by 20-25 German and Austrian members of the SS-Totenkopfverbände and 80-120 Wachmänner guards ("watchmen") who had been trained in a special SS facility at the Trawniki concentration camp near Lublin, Poland; all Wachmänner guards were trained in Trawniki. The guards were mainly ethnic Volksdeutsche East Germans and Ukrainians, with some Russians, Tatars, Moldovans, Latvians and Central Asians, all of whom had served in the Red Army. They were recruited by Karl Streibel, the commandant of the Trawniki camp, from prisoner-of-war camps for Soviet soldiers. The degree to which their recruitment was voluntary remains disputed; Although conditions in the Soviet POW camps were dire, some Soviet POWs collaborated with the Germans even before cold, famine, and disease began to ravage the POW camps in mid-September 1941.

The work at Treblinka was carried out under threat of death by Jewish prisoners organized into specialized Sonderkommando squads or labor detachments. In the reception area of Camp 2 Auffanglager each squad had a different colored triangle. The triangles made it impossible for new arrivals to try to blend in with members of the work detachments. The blue unit (Kommando Blau) manned the rail ramp and opened the doors of the freight cars. She met new arrivals, brought people who had died along the way, removed packages, and cleaned the wagon floor. The red unit (Kommando Rot), which was the largest detachment, unpacked and sorted the victims' belongings after they had been "processed". The red unit delivered these belongings to the police headquarters. storage, which were managed by the yellow unit (Kommando Gelb), which sorted items by quality, removed the Star of David from all outer garments, and extracted money sewn into linings. yellow was followed by the Desinfektionskommando, which disinfected the belongings, including the fur coats of the "processed" women. The Goldjuden ("Gold Jews") unit collected and counted banknotes, as well as appraising gold and jewellery.

A different group of about 300 men, called the Totenjuden ("Jews of the dead"), lived and worked in Camp 3 in front of the gas chambers. For the first six months the corpses were taken away for burial after the gold teeth had been extracted. Once cremation began in early 1943, they carried the corpses to the pits, restocked the pyres, crushed the remaining bones with sledgehammers, and collected the ashes for disposal. Each trainload of "deportees" brought to Treblinka consisted of an average of sixty heavily guarded wagons. They divided into three teams of twenty in the staging yard. Each set was processed within the first two hours of reversing on the ramp, and then prepared by the Sonderkommandos to exchange for the next set of twenty wagons.

Members of all work units were continually beaten by guards and often shot. Replacements were selected from the new arrivals. There were other work detachments that had no contact with the transports: the Holzfällerkommando ("lumberjack unit") felled trees and cut firewood, and the The Tarnungskommando ('disguise unit') camouflaged the camp structures. Another work detachment was in charge of cleaning the common areas. The Camp 1 Wohnlager residential complex contained barracks for some 700 Sonderkommandos who, when combined with the 300 Totenjuden who lived opposite the gas chambers, bringing their grand total to about a thousand at one time.

Many Sonderkommando prisoners hanged themselves at night. Suicides in the Totenjuden barracks occurred at the rate of 15 to 20 per day. Work crews were almost completely replaced every few days; members of the former labor were sent to their deaths, except for the most resistant.

Treblinka prisoner uprising

In early 1943, an underground Jewish resistance organization was formed in Treblinka with the aim of seizing control of the camp and escaping to freedom. The planned revolt was preceded by a long period of secret preparations. The clandestine unit was organized by a former Jewish captain in the Polish Army, Dr. Julian Chorążycki, who was described by fellow conspirator Samuel Rajzman as noble and essential to the action. His organizing committee included Zelomir Bloch (leadership), Rudolf Masaryk, Marceli Galewski, Samuel Rajzman Dr. Irena Lewkowska ("Irka", from the infirmary for Hiwis), Leon Haberman, Chaim Sztajer, Hershl (Henry) Sperling of Częstochowa and others. Chorążycki (who treated the German patients) committed suicide by poison on 19 April 1943 when faced with imminent capture, so the Germans were unable to discover the plot by torturing him. The next leader was another former Polish army officer, Dr. Berek Lajcher, who arrived on May 1. Born in Częstochowa, he had practiced medicine in Wyszków and was expelled by the Nazis to Węgrów in 1939.

The initial date of the revolt was set for June 15, 1943, but this had to be postponed. A fighter smuggled a grenade onto one of the early May trains carrying captured rebels from the Uprising. Warsaw Ghetto, which had begun on 19 April 1943. When he detonated it in the stripping area, the SS and guards panicked. After the explosion, Treblinka received only about 7,000 Jews from the capital fearing similar incidents; the remaining 42,000 Warsaw Jews were deported to Majdanek in return. The burning of disinterred corpses continued at full speed until late July. The Treblinka II conspirators became increasingly concerned about their future as the amount of work for them began to dwindle. With fewer transports arriving, they realized they were "next in line for the gas chambers".

Day of the revolt and survivors

The uprising began on a hot summer day on August 2, 1943 (Monday, a normal day off from gassings), when a group of Germans and 40 Ukrainians headed for a swim in the Bug River. they quietly opened the door of the armory near the railway tracks, with a key that had been previously duplicated. They had stolen 20 to 25 rifles, 20 hand grenades and several pistols and delivered them in a cart to the gravel retailer. At 3:45 p.m., 700 Jews launched an insurgency that lasted 30 minutes. They torched buildings, blew up a gas tank, and set surrounding structures on fire. A group of armed Jews attacked the main gate and others tried to scale the fence. Machine gun fire from about 25 Germans and 60 Ukrainian Trawnikis resulted in a near-total slaughter. Lajcher was killed along with most of the insurgents. Some 200 Jews escaped the camp. Half of them were killed after a car and horse chase. The Jews did not cut the telephone wires and Stangl called hundreds of German reinforcements, who arrived from four different cities. and set up roadblocks along the way. Supporters of the Armia Krajowa (Polish: "Home Army") ferried some of the surviving escapees across the river and others like Sperling ran 30 kilometers and were then aided and fed by the Polish villagers. Of those who made their way, around 70 are known to have survived until the end of the war, including the future authors of Treblinka's published memoirs: Richard Glazar, Chil Rajchman, Jankiel Wiernik and Samuel Willenberg.

Among the Jewish prisoners who escaped after burning down the camp were two 19-year-olds, Samuel Willenberg and Kalman Taigman, who arrived in 1942 and were forced to work there under threat of death. Taigman died in 2012 and Willenberg in 2016. Taigman stated of his experience: "It was hell, absolute hell." A normal man cannot imagine how a living person could have survived: murderers, born killers, who without a trace of remorse end up murdering anything'. Willenberg and Taigman immigrated to Israel after the war and devoted their last years to retell the story of Treblinka. Fugitives Hershl Sperling and Richard Glazar suffered from survivor's guilt and eventually committed suicide. Chaim Sztajer, who was 34 at the time of the uprising, had survived 11 months as Sonderkommando at Treblinka II and was instrumental in coordinating the uprising between the two camps. Following his escape in the uprising, Sztajer survived for over a year in the forest before the liberation of Poland. After the war, he emigrated to Israel and then to Melbourne, Australia, where later in life he built a model of Treblinka from memory which is currently on display at the Jewish Holocaust Center in Melbourne.

After the uprising

After the revolt, Stangl met with the head of Operation Reinhard, Odilo Globocnik and Inspector Christian Wirth in Lublin, and decided not to write a report, as no native Germans had been killed putting down the revolt. Stangl wanted rebuild the camp, but Globocnik told him that it would be closed soon and that Stangl would be transferred to Trieste to help fight the partisans there. The Nazi high command may have felt that Stangl, Globocnik, Wirth and other Reinhard staff knew too much and wanted to get rid of them by sending them to the front. With the death of almost all the Jews in the German ghettos (established in Poland), it would have had little point in rebuilding the facility. Auschwitz had sufficient capacity to meet the remaining extermination needs of the Nazis, making Treblinka redundant.

The new camp commander, Kurt Franz, previously his deputy commander, took over in August. After the war, he testified that the gassings had stopped by then.In reality, despite extensive damage to the camp, the gas chambers were intact and the killing of Polish Jews continued. Speed slowed, with only ten cars rolling on the ramp at a time, while the others had to wait. The last two rail transports of Jews were brought to the camp to be gassed from the Białystok ghetto on 18 and 19 April. August 1943. They consisted of 76 carriages (37 on the first day and 39 on the second), according to a statement published by the Armia Krajowa Information Office, based on observation of passing Holocaust trains through the village of Treblinka. The 39 wagons that arrived in Treblinka on 19 August 1943 carried at least 7,600 survivors of the Białystok Ghetto Uprising.

On October 19, 1943, Operation Reinhard was terminated by a letter from Odilo Globocnik. The next day, a large group of Arbeitskommando Jews who had worked on dismantling the camp structures in the previous weeks were loaded on the train and taken, via Siedlce and Chełm, to Sobibor to to be gassed on October 20, 1943. Franz followed Globocnik and Stangl to Trieste in November. Cleanup operations continued through the winter. As part of these operations, Jews from the surviving labor detachment dismantled the gas chambers brick by brick and used them to erect a farmhouse on the site of the former camp bakery. Globocnik confirmed its purpose as a secret guard post for a Nazi-Ukrainian agent to remain behind the scenes, in a letter he sent to Himmler from Trieste on 5 January 1944. A Hiwi guard called Globocnik Oswald Strebel, a Volksdeutscher Ukrainian ("ethnic German"), was given permission to bring his family from Ukraine for "surveillance reasons," Globocnik wrote; Strebel had worked as a guard at Treblinka II, he was instructed to tell visitors that he had been farming there for decades, but local Poles were well aware of the death camp's existence.

Treblinka II Operational Command

Irmfried Eberl

SS-Obersturmführer Irmfried Eberl was appointed the camp's first commandant on July 11, 1942. He was a psychiatrist at the Bernburg Euthanasia Center and the only chief physician to command a death camp during World War II. According to some, his poor organizational skills caused the Treblinka operation to turn disastrous; others point out that the number of incoming transports reflected the unrealistic expectations of the Nazi high command of Treblinka's ability to "process"; these prisoners. The early gassing machinery frequently broke down due to overuse, forcing the SS to shoot Jews to be suffocated. The workers did not have enough time to bury them and the mass graves overflowed. According to the testimony of his colleague Unterscharführer Hans Hingst, Eberl's ego and thirst for power exceeded his capacity: " so many transports arrived that the disembarkation and gassing of the people could no longer be managed". On the incoming Holocaust trains to Treblinka, many of the Jews locked inside guessed correctly what was going to happen to them. The smell of decomposing corpses could be smelled up to 10 kilometers away.

Oskar Berger, a Jewish eyewitness, one of the 100 people who escaped during the 1943 uprising, spoke about the state of the camp when he arrived there in August 1942:

When they unloaded us, we had a first paralyzing image: there were hundreds of human bodies everywhere. Lots of packages, clothes, suitcases, everything was a mess. The men of the German and Ukrainian SS stood in the corners of the barracks and shot blindly against the crowd.

When Globocnik made a surprise visit to Treblinka on 26 August 1942 with Christian Wirth and Wirth de Bełżec's assistant Josef Oberhauser, Eberl was fired on the spot. incompetent the tens of thousands of corpses, using inefficient methods of killing, and not adequately concealing the mass murder. Eberl was transferred to Berlin, closer to the operational headquarters in Hitler's Chancellery, where the main architect of the Holocaust, Heinrich Himmler, had just stepped up the pace of the program. Globocnik assigned Wirth to remain in Treblinka temporarily to help to clean up the camp. On August 28, 1942, Globocnik suspended the deportations. He chose Franz Stangl, who had previously been the commandant of the Sobibór death camp, to take over command of the camp as Eberl's successor. Stangl was known as a competent administrator with a good understanding of the project's objectives, and Globocnik was confident that he would be able to regain control.

Franz Stangl

Stangl arrived at Treblinka at the end of August 1942. He replaced Eberl on 1 September. Years later, Stangl described what he first saw when he came on the scene, in a 1971 interview with Gitta Sereny:

The road ran by the railroad. When we were about fifteen or twenty minutes by car from Treblinka, we started seeing corpses near the line, first only two or three, then more, and as we drove to Treblinka station, there was what looked like hundreds of them, just lying there, obviously they had been there for days, in the heat. At the station there was a train full of Jews, some dead, some still alive... that too, seemed to have been there for days.

Stangl reorganized the camp, and transports of Jews from Warsaw and Radom began arriving again on September 3, 1942. According to Israeli historian Yitzhak Arad, Stangl wanted the camp to look attractive, so he ordered for the roads to be paved in the Wohnlager administrative complex. Flowers were planted along Seidel Straße, as well as near SS housing. He ordered that all arriving prisoners be greeted by the SS with a verbal announcement translated by the Jewish workers. The deportees were told who were at a transit point en route to the Ukraine. Some of their questions were answered by Germans using lab coats as tools of deception. Stangl sometimes carried a whip and wore a white uniform, for which the prisoners nicknamed him the "White Death". Although he was directly responsible for the operations of the camp, according to his own testimony, Stangl limited his contact with the Jewish prisoners as much as possible. He claimed that he rarely interfered with the cruel acts perpetrated by his subordinate officers in the camp.He became desensitized to the killings and came to perceive the prisoners not as human but simply as "burden."; it had to be destroyed, he said.

Song of Treblinka

According to post-war accounts, when the transports were temporarily halted, then Deputy Commander Kurt Franz wrote lyrics for a song intended to celebrate the Treblinka death camp. Actually, the prisoner Walter Hirsch wrote them for him. The melody came from something Franz remembered from Buchenwald. The music was cheerful, in the key of D major. The song was taught to Jews assigned to work in the Sonderkommando. They were forced to memorize it by the evening of their first day in the camp. Unterscharführer Franz Suchomel recalled the letter as follows: "we only know the word of the Commander. / We only know obedience and duty. / We want to keep working, working, / until a bit of luck calls us at some point. Hooray!".

A musical ensemble was formed, under duress, by Artur Gold, a popular Jewish composer from Warsaw between the wars. He arranged the theme song for Treblinka for the 10-piece prisoners' orchestra that he conducted. Gold arrived in Treblinka in 1942 and played music in the SS mess hall at the Wohnlager on German orders. He died during the uprising.

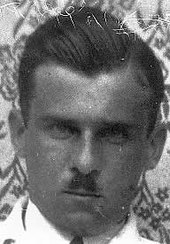

Kurt Franz

After the Treblinka revolt in August 1943, and the completion of Operation Reinhard in October 1943, Stangl went with Globocnik to Trieste in northern Italy, where SS reinforcements were needed. The third The last commander of Treblinka II was Kurt Franz, nicknamed Lalka by the prisoners (Polish: "the doll") because he had "an innocent face". surviving, Franz shot and beat prisoners for minor infractions or had them torn to pieces by his dog Barry. He managed Treblinka II until November 1943. Subsequent clearance of the Treblinka II perimeter was completed by prisoners from nearby Treblinka IArbeitslager in the following months. Franz's deputy was Hauptscharführer Fritz Küttner, who maintained a network of Sonderkommando informants and carried out the manual killings.

Kurt Franz kept a photo album against orders never to take pictures inside Treblinka. He called it Schöne Zeiten ("The Good Times"). His album is a rare source of images illustrating mechanized grave digging, brickwork in Małkinia, and the Treblinka Zoo, among others. Franz was careful not to photograph the gas chambers.

The Treblinka I gravel quarry was fully operational under the command of Theodor van Eupen until July 1944, and new forced laborers were sent from Sokołów by Kreishauptmann Ernst Gramss. Mass shootings continued until 1944. With Soviet troops already close, the Trawnikis executed the last 300-700 Sonderkommandos with incriminating evidence in late July 1944, well after the official closure. from the camp. Strebel, the ethnic German who had been installed in the farmhouse built in place of the original camp bakery using bricks from the gas chambers, set the building on fire and fled to avoid capture.

Arrival of the Soviets

In late July 1944, Soviet forces began to approach from the east. The departing Germans, having already destroyed most of the direct evidence of the genocide, burned down the surrounding villages, including 761 buildings in Poniatowo, Prostyń and Grądy. Many families were killed. The grain fields that had once fed the SS were burned. On 19 August 1944, German forces blew up the church in Prostyń and its bell tower, the last defensive strongpoint against the Red Army. in the area. When the Soviets entered Treblinka on 16 August, the killing zone had been leveled, plowed, and planted with lupins. What remained, wrote Soviet war correspondent Vasili Grossman, were small pieces of bone on the ground, human teeth, pieces of paper and cloth, broken plates, jars, shaving brushes, rusty pots and pans, cups of all sizes, smashed shoes, and strands of human hair. The path leading to the camp was completely black. Until mid-1944, the remaining prisoners regularly scattered human ashes (up to 20 carts per day) along the road for 2 kilometers in the direction of Treblinka I. When the war ended, destitute and starving locals began to walk the road. Black Road (as they began to call it) in search of man-made molten gold nuggets to buy bread.

Early attempts at preservation

The new Soviet-installed government did not preserve the evidence from the camp. The scene was not legally protected at the end of World War II. In September 1947, 30 students from the local school, led by their teacher Feliks Szturo and the priest Józef Ruciński, collected larger bones and skull fragments in the farmers' wicker baskets and buried them in a single mound. In the same year, the first commemoration committee Komitet Uczczenia Ofiar Treblinki (KUOT; Committee for the Remembrance of Treblinka Victims) was formed in Warsaw and launched a design competition for the monument.

Stalinist officials did not allocate funds for the design competition or the monument, and the committee was dissolved in 1948; by then many survivors had left the country. In 1949, the city of Sokołów Podlaski protected the camp with a new fence and gate. A work team with no archaeological experience was sent to create gardens on the grounds. In 1958, after the end of Stalinism in Poland, the Warsaw provincial council declared Treblinka a place of martyrdom. Over the next four years, 127 hectares of land that had formed part of the camp were purchased from 192 farmers in the villages. from Prostyń, Grądy, Wólka Okrąglik and Nowa Maliszewa.

Construction of the memorial

The construction of an 8-meter-high monument designed by sculptor Franciszek Duszeńko was inaugurated on April 21, 1958 with the laying of the cornerstone on the site of the former gas chambers. The sculpture represents the trend towards large avant-garde forms introduced in the 1960s throughout Europe, with a cracked granite tower at its center and surmounted by a mushroom-shaped block carved with abstract reliefs and Jewish symbols. Treblinka was declared a national martyrdom monument on 10 May 1964 during an official ceremony attended by 30,000 people. The monument was unveiled by Zenon Kliszko, the Sejm Marshal of the Republic of Poland, in the presence of survivors of the uprising of Treblinka from Israel, France, Czechoslovakia and Poland. The camp custodian's house (built nearby in 1960) became an exhibition space after the collapse of communism in Poland in 1989 and the custodian's retirement; it opened in 2006. It was later expanded and became a branch of the Siedlce Regional Museum.

Deaths

There are many estimates of the total number of people killed at Treblinka; most scholarly estimates range between 700,000 and 900,000, meaning that more Jews died in Treblinka than in any other Nazi death camp apart from Auschwitz. The Treblinka museum in Poland claims that at least 800 000 people died in Treblinka. Yad Vashem, which is Israel's Holocaust museum, puts the death toll at 870,000; and the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum gives a range of 870,000 to 925,000.

First estimates

The first estimate of the number of people killed at Treblinka came from Vasili Grossman, a Soviet war reporter, and later writer, who visited Treblinka in July 1944 as Soviet forces marched west through Poland. He published an article called "Hell was called Treblinka", which appeared in the November 1944 issue of Znamya, a monthly Russian literary magazine.In the article he claimed that 3 million people had been murdered. in Treblinka. He may not have been aware that the short station platform at Treblinka II greatly reduced the number of carriages that could be unloaded at the same time, and may have adhered to the Soviet trend of exaggerating Nazi crimes for the purposes of propaganda. In 1947, Polish historian Zdzisław Łukaszkiewicz estimated the death count at 780,000, based on the accepted record of 156 transports averaging 5,000 prisoners each.

Trials and declarations

The Treblinka trials of the 1960s took place in Düsseldorf and produced the two official estimates for West Germany. During Kurt Franz's trial in 1965, the Düsseldorf Assize Court concluded that at least 700,000 people were murdered at Treblinka, following a report by Dr. Helmut Krausnick, director of the Institute for Contemporary History. Franz Stangl in 1969, the same court reassessed the number to at least 900,000 after new evidence from Dr. Wolfgang Scheffler.

A principal witness for the prosecution in Düsseldorf in the trials of 1965, 1966, 1968 and 1970 was Franciszek Ząbecki, employed by the Deutsche Reichsbahn as rail traffic controller in the village of Treblinka since 22 May 1941. In 1977 he published his book Old and New Memories, in which he used his own records to estimate that at least 1.2 million people died at Treblinka. His estimate he was based on the maximum capacity of a train during the 1942 Grossaktion Warsaw rather than its annual average. The original German waybills in his possession did not have the number of prisoners listed. Ząbecki, Polish member of the railway staff before the war, he was one of the few non-German witnesses to see most of the transports entering the camp; was present at Treblinka station when the first Holocaust train arrived from Warsaw. Ząbecki was a member of the Armia Krajowa (Polish: Home Army), which formed the bulk of the Polish resistance movement in World War II, and kept a daily record of extermination transports. He also clandestinely photographed the burning perimeter of Treblinka II during the uprising in August 1943. Ząbecki witnessed the last set of five closed freight cars carrying Sonderkommandos to the Sobibór gas chambers on 20 October 1943. In 2013, his son Piotr Ząbecki wrote an article about him for Życie Siedleckie which revised the number to 1,297,000. Ząbecki's daily records of transports to the camp, and information demographic information on the number of people deported from each ghetto to Treblinka, were the two main sources for estimating the death toll.

In his 1987 book, Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka: The Operation Reinhard Death Camps, Israeli historian Yitzhak Arad stated that at least 763,000 people were killed at Treblinka between July 1942 and April of 1943. A considerable number of other estimates followed: see table (below).

Höfle Telegram

Another source of information became available in 2001. The Höfle Telegram was an encrypted message sent to Berlin on December 31, 1942 by Operation Deputy Commander Reinhard Hermann Höfle, detailing the number of Jews deported by the Deutsche Reichsbahn (DRB) to each of the Operation Reinhard death camps up to that point. Discovered among declassified documents in Britain, it shows that, according to the official count of the German Transport Authority, 713,555 Jews were sent to Treblinka in 1942. The number of deaths was probably higher, according to Armia Krajowa's statements. . According to the telegram and additional undated German evidence for 1943 listing 67,308 people deported, historian Jacek Andrzej Młynarczyk estimated that according to the official DRB count, 780,863 people were taken by the Deutsche Reichsbahn to Treblinka.

Estimates table

Estimate Source Notes Year Work at least 700 000 Helmut Krausnick First calculation of Federal Germany; used during the trial of Kurt Franz 1965 at least 700 000 Adalbert Rückerl Director of the Central Authority for the Investigation of Nazi Crime in Ludwigsburg N/A at least 700 000 Joseph Billig French historian 1973 700 000–800 000 Czesław Madajczyk Polish historian 1970 700 000–900 000 Robin O'Neil of Belzec: Stepping Stone to Genocide; Hitler's answer to the Jewish Question, published by JewishGen Yizkor Books Project 2008 713 555 Telegram Höfle discovered in 2001; official Nazi estimate until the end of 1942 1942 at least 750 000 Michael Berenbaum of the entry of his encyclopedia on “Treblinka” 2012 Encyclopædia Britannica at least 750 000 Raul Hilberg American historian 1985 The Destruction of European Jews 780 000 Zdzisław Łukaszkiewicz Polish historian responsible for the first estimate of the count of deaths based on 156 transports with 5,000 prisoners each, published in his monograph Obóz zagłady w Treblince 1947 780 863 Jacek Andrzej Młynarczyk quoted by Timothy Snyder; combines the Höfle Telegram with undated German tests of 1943 2004 at least 800 000 Treblinka Field Museum use tests of Franciszek Ząbecki and ghettos N/A 850 000 Yitzhak Arad Israeli historian who estimates 763 000 deaths only between July 1942 and April 1943 1983 Treblinka, Hell and Revolt at least 850 000 Martin Gilbert British historian 1993 870 000 Yad Vashem Israel Holocaust Museum N/A 870 000 to 925 000 United States Holocaust Museum of the article "Treblinka: Chronology"; excludes deaths from forced labour in Treblinka I N/A 876 000 Simon Wiesenthal Center 738 000 Jews from the General Government; 107 000 from Bialystok; 29 000 Jews from other parts of Europe; and 2 000 Gypsies N/A at least 900 000 Wolfgang Scheffler Second estimate of Federal Germany; used during the trial of Franz Stangl 1970 912 000 Manfred Burba German historian 2000 at least 1 200 000 Franciszek Ząbecki Polish witness 1977 Old and New Memories 1 297 000 Piotr Ząbecki review of Franciszek Ząbecki's estimate by your son Piotr 2013 He was a humble man 1 582 000 Ryszard Czarkowski Polish historian 1989 3 000 000 Vasili Grossman Soviet journalist 1946 The Hell of Treblinka

- The information in the rows with a last empty column comes from Dam im imię na wiekiPage 114.

Treblinka Trials

The first official trial for war crimes committed at Treblinka was held in Düsseldorf between October 12, 1964 and August 24, 1965, preceded by the 1951 trial of the SS-Scharführer Josef Hirtreiter, who was triggered by war crimes charges unrelated to his service in the camp. }} The trial was delayed because the United States and the Soviet Union had lost interest in prosecuting German war crimes with the onset of the Cold War. Many of the more than 90,000 Nazi war criminals registered in German archives were serving in high office under Federal Chancellor Konrad Adenauer. In 1964 and 1965, eleven former staff members of the Cold War camps SS were put on trial by West Germany, including Commander Kurt Franz. He was sentenced to life in prison, along with Artur Matthes (Totenlager) and Willi Mentz and August Miete (both from Lazaret). Gustav Münzberger (gas chambers) received 12 years, Franz Suchomel (gold and money) 7 years, Otto Stadie (operation) 6 years, Erwin Lambert (gas chambers) 4 years and Albert Rum (Totenlager) 3 years. Otto Horn (details of the corpses) was acquitted.

The deputy commander of Treblinka II, Franz Stangl, escaped with his wife and children from Austria to Brazil in 1951. Stangl found work at a Volkswagen factory in São Paulo. Austrian authorities knew of his role in the mass murder of Jews, but Austria did not issue an arrest warrant until 1961. Stangl was registered under his real name at the Austrian consulate in Brazil. Another six years passed before Nazi hunter Simon Wiesenthal tracked him down and triggered his arrest. After his extradition from Brazil to West Germany, Stangl was tried for the deaths of around 900,000 people. He admitted to the murders, but argued: "My conscience is clear." I was just doing my duty. Stangl was found guilty on October 22, 1970, and sentenced to life in prison. He died of heart failure in prison in Düsseldorf on June 28, 1971.

Material gains

The theft of cash and valuables, collected from gassing victims, was carried out by the highest ranking SS men on an enormous scale. It was a common practice among the high command of concentration camps everywhere; the commandants of the Majdanek concentration camp, Koch and Florstedt, were tried and executed by the SS for the same offense in April 1945. When high-ranking officers went home, they sometimes requested a private locomotive from Klinzman and Emmerich at the Treblinka station to transport his "gifts" personal to Małkinia for a connecting train. They would then leave the camp in cars without any incriminating evidence on their person, and then arrive in Małkinia to transfer the assets.

The total amount of material obtained by Nazi Germany is unknown, except for the period between August 22 and September 21, 1942, when 243 freight cars were shipped and searched. Globocnik provided a written count to Reinhard's headquarters on 15 December 1943 with a profit of SS 178,745,960.59 RM, including 2,909.68 kg of gold, 18,733.69 kg of silver, 1,514 kg of platinum and US$249,771.50, as well as 130 diamond solitaires, 2,511.87 carats of brilliants, 13,458.62 carats of diamonds and 114 kg of pearls. The amount of loot Globocnik stole is unknown; Suchomel claimed in court to have filled a box with one million Reichsmarks for him.

Archaeological studies

Neither Jewish religious leaders in Poland nor authorities allowed archaeological excavations at the death camp out of respect for the dead. Approval for a limited archaeological survey was first issued in 2010 to a British team from Staffordshire University using non-invasive technology and Lidar remote sensing. Soil resistance was analyzed at the site with ground penetrating radar. Features that appeared to be structural were found, two of which were thought to be the remains of the gas chambers, and study was allowed to proceed.

The archaeological team that conducted the search discovered three new mass graves. The remains were reinterpreted out of respect for the victims. In the second excavation, finds included yellow tiles patterned with a perforated mullet star resembling a Star of David and foundation construction with a wall. The star was soon identified as the logo of the Polish ceramic factory that manufactures tiles, founded by Jan Dziewulski and the brothers Józef and Władysław Lange (Dziewulski i Lange – D✡L since 1886), nationalized and renamed under communism after the war. As forensic archaeologist Caroline Sturdy Colls explained, the new evidence was important because the second gas chambers built at Treblinka were housed in the only brick building in the camp; Colls claimed that this provides the first physical evidence of its existence. In his memoirs describing his time in the camp, survivor Jankiel Wiernik says that the floor of the gas chambers (which he helped build) were made of similar tiles. The discoveries became a subject of the 2014 Canal documentary Smithsonian. More forensic work is planned.

March of the Living

The Treblinka museum receives its most daily visitors during the annual March of the Living educational program, which brings young people from around the world to Poland to explore the remains of the Holocaust. Visitors whose main destination is the march at Auschwitz II-Birkenau, visit Treblinka on the days before. In 2009, 300 Israeli students attended the ceremony led by Eli Shaish of the Ministry of Education. In total, 4,000 international students visited the museum. In 2013, the number of students who attended, prior to the Auschwitz commemorations, was out of 3,571. In 2014, 1,500 foreign students visited the museum.

Leaders of Operation Reinhard and commanders of Treblinka

Name Rank Function and notes Cias Operation Reinhard Leaders Odilo Globocnik SS-Hauptsturmführer and SS-Polizeiführer at the time (capitán and SS police chief) Operation Reinhard leader Hermann Höfle SS-Hauptsturmführer (capitán) Operation Reinhard Coordinator Christian Wirth SS-Hauptsturmführer at the time (capitán) Operation Reinhard Inspector Richard Thomalla SS-Obersturmführer at the time (first lieutenant) chief of the construction of the extermination camp during Operation Reinhard Erwin Lambert SS-Unterscharführer (cabo) gas chamber construction manager during Operation Reinhard (large gas chambers) Treblinka commanders Theodor van Eupen SS-Sturmbannführer (general), commander of Treblinka I Arbeitslager15 November 1941 – July 1944 (cleaning) head of the forced labour camp Irmfried Eberl SS-Obersturmführer (first lieutenant), commander Treblinka IIJuly 11, 1942 – August 26, 1942 transferred to Berlin by incompetent Franz Stangl SS-Obersturmführer (first lieutenant), second commander Treblinka II1 September 1942 – August 1943 transferred to Treblinka from the Sobibor extermination camp Kurt Franz SS-Untersturmführer (second lieutenant), last commander Treblinka IIAugust (gaseos) – November 1943 a deputy commander in August 1943 following the revolt of prisoners of the camp Deputy commanders Karl Pötzinger SS-Oberscharführer (staffing), deputy commander Treblinka II cremation chief Heinrich Matthes SS-Scharführer (sargente), Deputy Commander Chief of the extermination area

Contenido relacionado

October 12 °

Jose Antonio Paez

Antonio Meucci