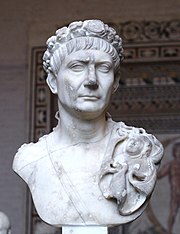

Trajan

Marcus Ulpius Trajan (Italic, September 18, 53-Selinus, c. August 11, 117) was Roman emperor from the year 98 until his death in 117. Being a natural of Bética, he is considered the first provincial emperor, specifically coming from an indigenous Turdetana family, although related to another of ancient Italic settlers settled in this province. He was the second of the traditionally called Antonina dynasty or, according to a recent proposal, Ulpius-Aelia dynasty. Trajan is remembered as a successful soldier-emperor who presided over the greatest military expansion in Roman history up to the time of his death, as well as for his philanthropic activity.

Born in the city of Itálica, in Baetica, Trajan's family was of Italic or, more likely, Turdetan origin. Trajan became a prominent military man already during the reign of Emperor Domitian, serving as legatus legionis in Hispania Tarraconensis. In the year 89 he supported Domitian against a revolt on the Rhine led by Lucio Antonio Saturnino. In September 96, Domitian was murdered in a conspiracy, succeeded by Nerva, an elderly and childless senator who proved unpopular in the army. After a brief and tumultuous year in power, culminating in a revolt by members of the Praetorian Guard, Nerva was forced to adopt Trajan as his heir and successor.

As a civil administrator, Trajan is best known for his extensive program of construction of public buildings that reshaped the city of Rome and left behind numerous enduring monuments such as Trajan's Forum, Trajan's Market, and Trajan's Column. However, he went as a military commander so he celebrated his greatest triumphs. In 101 he launched a punitive expedition against the Dacia kingdom ruled by King Decebalus, defeating the Dacian army near Tapae in 102 and finally conquering the country in 106. A few years later, he went further east and annexed the Nabataean kingdom, establishing the province of Arabia Petrea. After a period of relative peace, he launched his final campaign in 113 against Parthia. He reached the city of Susa (present-day Iran) in 116, thus achieving the greatest expansion of the Roman Empire. During this campaign, Trajan fell ill and died while returning to Rome. He was deified by the Senate and his ashes were interred in a chamber at the foot of Trajan's Column. He succeeded his second nephew and his pupil Adriano.

At the time of his death his full name day was Imperator Caesar Divi Nervae filius Nerva Traianus Optimus Augustus Germanicus Dacicus Parthicus. After his official apotheosis he was called Divus Traianus , sometimes adding one of the other cognomina , especially Augustus and Parthicus .

Family and origins

The Emperor Trajan was born in the Roman city of Itálica (now Santiponce), attached to the province of Baetica, one of the most intensely Romanized in the Empire, on September 18, 53. Some authors, following Casio Dion, have argued or considered the year 56 as the year of his birth.

He was a member of the Ulpia gens of Itálica, his family's homeland, although there are discrepancies among specialists regarding the origin of the clan. For one part, following an ancient opinion, his ancestors would have settled at the end of the III century a. C. in the locality. They were Italian veterans from Tuder, in the region of Umbria (Italy), who settled in the province of Hispania Ulterior after the Second Punic War. Against this opinion, other scholars advocate an autochthonous origin, Trajan being a hispanus, a descendant of one of the families that, by virtue of their wealth or lineage, were early Romanized and settled in the Roman colonies and municipalities of the Iberian Peninsula.

His father was Marco Ulpio Trajano, a senator in favor of the Flavians, and his sister Ulpia Marciana. Regarding his mother, there are different opinions. Traditionally she has been called Marcia and related to the Marcios Bareas, citing the nomenclature of her daughter, Marciana, and of certain figlinae belonging to the imperial family related to the Marcios. Another proposal indicates that she was a Ulpia and that the emperor's father entered his wife's gens by adoption, perhaps in a testamentary way. This proposal is based on the classical sources themselves, specifically in the Epitome de Caesaribus. Finally, a third proposal is simply limited to certifying that Trajan's mother is still an Ignota.

Trajan was married to Pompeii Plotina who is considered a native of Nemausus or of Itálica itself, being that in the latter case she is also considered a possible cousin of the emperor.

Early Years

Like his father, Trajan was loyal to the Flavian house. A hard-working young man, he rose through the ranks of the Roman army, serving on some of the most contentious parts of the Imperial frontier, in various parts of the Empire, from his native Spain to Syria, the Danube and Germania. In 76- 77, Trajan's father was governor of Syria (Legatus pro praetore Syriae). There, at the age of 24, Trajan commanded a legion.

He followed the various stages of the ordinary senatorial cursus honorum; he was quaestor, praetor and legate. This gave him the possibility of acquiring some knowledge about the borders and the life of the soldier, first, and of the officers, later. He stood out in the Roman army in the time of Domitian. He was a military tribune (tribunus legionis) in Syria, and legate of Legio VII Gemina in Hispania, with whose troops he successfully crushed the revolt of Antonio Saturnino in Inferior Germany in 89. Later he was consul in the year 91, along with Manio Acilio Glabrión. Around that year, he took Apollodorus from Damascus to Rome with him.

In the year 96 he became governor of Lower Germany, serving on the German border, one of the most problematic in the empire, along the Rhine River. He lived in Mainz and Cologne (Germany). He took part in the Emperor Domitian's wars against the Germanic peoples, and was known as one of the best commanders in the empire when, in the year 96, Domitian was assassinated.

Ascension to the throne

On September 18, Nerva succeeded Domitian. He was an old, childless senator who was very unpopular in the military and he needed to do something to win his support. After a brief and tumultuous year in power, a revolt by members of the Praetorian Guard forced Nerva to adopt the highly popular Trajan, then Governor of the Germania Superior, as his heir and successor, in the spring or summer of 97, preferring him to Marco Cornelio Nigrino Curiacio Materno. The emperor made him participate in his government. His rapid rise was due to a number of reasons: Nerva was in trouble over a Praetorian revolt, and the old group of senators, uncompromising in Domitian's later days, may have seen fit to promote a good general of recent nobility., but solid, popular, and above all at the head of the legions closest to Italy. In addition, it is possible that other members of the Iberian elite, especially Lucio Licinio Sura, later chosen by Trajan as his successor in the Germania Superior, had a weight in his rise. According to the Historia Augusta, it was the future emperor Hadrian who brought the news of his adoption to Trajan. Nerva died unexpectedly on January 28, 98, and his highly respected adoptive son, Trajan, it happened to him without incident. Trajan kept close to the borders of the Rhine and the Danube. With Domitian's terrifying rule still fresh, he was welcomed with open arms by the Senate. As a consequence, the governor of Syria Marco Cornelio Nigrino Curiacio Materno, considered by Nerva as a possible successor and with a prestigious military career under Domitian, was evaluated as a potential rival of Trajan and was abruptly dismissed and provisionally replaced by Aulus. Larcio Prisco, legate of the Legio IV Scythica, who temporarily held the office of governor as pro legatus consularis without even holding praetorian rank, until the arrival of Javoleno Prisco in 99.

Emperor

Trajan was in Cologne when his second nephew Hadrian, future emperor and then tribune, told him of Nerva's death. He became emperor on January 28, 1998, at the age of 45. Being the first non-Italic emperor showed that the Italian peninsula was losing its central role in Roman politics. Once made emperor, he did not rush to the capital, instead merely substituting for some unfaithful men, punishing the Praetorians involved in the revolt against his predecessor, halving the traditional donation to celebrate his accession to the throne. throne. One of his first actions was to improve the road network between Mogontiacum (Mainz) and Augusta Vindelicorum (Augsburg). He further initiated the construction of a limes to secure the Decuman Fields ( Agri decumates) , Germanic lands on the right side of the Rhine, which had been won for the empire under Domitian.. When he was satisfied with the security of the territory between the Rhine and the Danube he marched on Rome, where he made his triumphal entry two years after being made emperor, having secured the Rhenish frontier.

Relationship with the Senate

The new Roman Emperor was welcomed by the people of Rome with great enthusiasm, which he justified by ruling well and without the bloodshed that had marked the reign of Domitian. He freed many people who had been unjustly imprisoned by Domitian and returned much of the private property that Domitian had confiscated; a process started by Nerva before his death. His popularity was such that over time the Roman Senate conferred on Trajan the honorary title of optimus , that is, "Optimal".

During the ceremony in the Senate, on the occasion of his accession to the imperial throne, Senator Pliny dedicated a famous and endless Panegyric (Panegyricus Traiani) to him in which he asked that the Senate be granted a greater involvement in conducting the affairs of the public administration of the State; Trajan observed that rule and called many of the "conscript fathers" (senators) to govern the Roman provinces. He kept a very strong control, scrupulously dealing with the affairs of the various provinces and assuming, for example, permits for the construction of public buildings. This allowed him to unmask and punish many senators accused of the crime of embezzlement, who had taken advantage of the lenient policy of the previous emperor, Nerva. Trajan used a judicial body created by him to investigate these crimes, the Consilium Principis, which included the best jurists of the time. Many were investigated for cases of bad government in the provinces, although the Senate itself generally handed down favorable sentences.

Since before he became emperor, he was married to Pompeii Plotina, although they had no children. Cassius Dio suggests that Trajan drank heavily and that he had a soft spot for boys. “I know, of course, that he was into boys and wine, but if he committed or endured any heinous or infamous act as a result of this, he would have been censured; instead, he drank all the wine he wanted, but he remained sober, and in relation to the boys he hurt no one." This sensibility influenced his rule on at least one occasion, leading him to favor the king of Edessa for the appreciation he had for his handsome son: «On this occasion, however, Abgaro, induced in part by the persuasion of his son Arbandes, who was beautiful and in full and proud youth and by enjoying the favor of Trajan, and in Partly out of fear of the presence of the latter, he met him on the road, apologized to him and obtained forgiveness, since he had a powerful intercessor in the boy".

On the other hand, he was one of the most serious and correct emperors, characteristics that made him the best of princes who knew how to manage public affairs well. Power did not corrupt him, nor did he ever use his title and his power to evade the law, always acknowledging the latter's primacy even over his own. He eliminated from the label all the rituals brought from the East, such as the hugging of the feet or the kissing of the hands. He knew how to make himself loved by everyone, especially the two most important classes: the Senate and the army. He was a conservative, convinced that progress would come more from orderly administration than from imposing reforms.

The wars against the Dacians

For history, Trajan stands out above all as a military commander, particularly for his conquests in the Near East, but initially for the two wars against Dacia, in what is now Romania—its conquest (101-102), then its reconquest of the transdanubian border kingdom of Dacia—a region that had troubled Roman thought for more than a decade with the unfavorable (and, to some, shameful) peace brokered by Domitian's retainers. During Trajan's reign one of the most important Roman successes was the victory over the Dacians. The first important confrontation between the Romans and the Dacians occurred in the year 87 and was initiated by Domitian. The Praetorian prefect Cornelius Fusco crossed the Danube with five or six legions on a bridge of boats and advanced towards Banat (in Romania). They were surprised by a Dacian attack in Tapae (near the town of Bucova, in Romania). The Legion V Alauda was crushed and Cornelio Fusco was sacrificed. The victorious general was originally called Diurpaneo (see Manea, p. 109), but after this victory he was called Decebalus (the brave).

The Emperor Domitian had campaigned against Dacia from 86 to 87, without securing a decisive result, and Decebalus had brazenly disobeyed the terms of the peace (89) he had agreed upon at the end of this campaign.

With this offensive to expand territories, Trajan put an end to a policy followed since the time of Augustus of keeping the Empire within certain limits and waging simple defensive wars. The only exception had been the conquest of Britain under Claudius. Around March 101, Trajan began his first war against the Dacians led by Decebalus. To do this, Trajan crossed to the northern bank of the Danube over a stone bridge he had built, crossed the Iron Gates, and headed towards the capital, Sarmizegetusa. He attacked the Dacian kingdom with four legions, defeated the Dacian army near from a port called Tapae, in the so-called Second Battle of Tapae. Trajan's troops, however, were damaged in the encounter, and he desisted from any further campaign for the remainder of the year, to treat the wounded, receive reinforcements, and regroup.

During the subsequent winter, King Decebalus launched a counterattack by crossing the Danube further downstream, but it was repulsed. Trajan's army pushed deeper into Dacian territory and forced King Decebalus into submission the following year, after Trajan had camped a few kilometers from the capital, Sarmizegetusa Regia.

Upon returning to Rome, he obtained the title of "Dacicus" (Dacicus) and the triumph was commemorated, held at the Tropaeum Traiani. However, Decebalus, left to fend for himself, in 105 undertook an invasion into Roman territory, attempting to rouse some of the north-river tribes against Rome. Trajan set out again, setting out from Ancona and reaching the banks of the Danube. The sources speak of 13 legions transferred to definitively subdue that land rich in gold and that town that during the kingdom of Domitian had passed Moesia to iron and fire. He created two new legions, the Legio II Traiana fortis and the Legio XXX Ulpia Victrix.He had built, with the design of Apollodorus of Damascus, his massive bridge over the Danube, an undertaking very similar to that of Caesar with Ariovistus.

He completely conquered Dacia in 106, despite the strength and vehemence of the Dacians, warriors who, if they did not fall in battle, committed suicide for their god Zalmoxis. The advance of the army of Rome to the capital Sarmizegetusa Regia suffered no obstacles thanks to its numerical superiority, logistics and tactics already consolidated by centuries of wars and sieges. The proven tortoise formation, for example, was the focus of siege tactics in Dacia. On the occasion of these battles, moreover, Trajan introduced a new weapon, the carroballista, the true ancestor of the field cannon, a means that combined the necessary mobility in battle with great power and that contributed to the Roman victory. The Romans took the Dacian capital, Sarmizegetusa, and destroyed it. Decebalus committed suicide, and his severed head was displayed in Rome on the steps leading up to the Capitol. He founded a new city, "Colonia Ulpia Traiana Augusta Dacica Sarmizegetusa", in another place than the previous Dacian capital, although it bore the same name, Sarmizegetusa. He colonized Dacia with the Romans and annexed it to the empire as a new province. Trajan's Dacian campaigns benefited the finances of the Empire through the acquisition of Dacian gold mines. In addition, he discovered the hidden treasure of Decebalus, amounting to 165 tons of gold and twice as much silver. These wars are commemorated in Trajan's Column, which was erected in conjunction with the Forum (Trajan's Forum), where it was placed to celebrate the great victory.

Expansion in the East

At about the same time Rabbel II Soter, one of Rome's client kings, died. This event may have prompted the annexation of the Nabataean kingdom, although the manner and formal reasons for the annexation are uncertain. Certain epigraphic evidence suggests a military operation, with forces from Syria and Egypt. What is clear, however, is that by the year 107, Roman legions were established in the region around Petra and Bostra, as shown on a papyrus found in Egypt. This kingdom of the Nabataeans became a Roman province with the name of Arabia Petrea, which covers the south of present-day Jordan and the northwest of Saudi Arabia. With the annexation of the Nabataean kingdom, territorial continuity between Egypt and the Asian provinces was ensured. From then on, the entire Mediterranean remained in the hands of the Romans, who considered it "a private lake", conferring on it the title of mare Nostrum. Judea and Arabia Nabatea would be two excellent starting platforms for Trajan's future eastern campaigns.

Peace Period

For the next seven years, Trajan ruled as a civil emperor, but with the same success as before. It was around this time that he corresponded with Pliny the Younger on the subject of how to handle the Christians of Pontus, telling Pliny to leave them alone unless they openly practiced their religion. He built several new buildings, monuments, and roads in Italy. and his native Spain. His magnificent complex in Rome was raised to commemorate his victories in Dacia, and was largely financed by the spoils of that campaign; it consisted of a forum, Trajan's Column and Trajan's market that are still preserved in present-day Rome. He was also a prolific builder of triumphal arches, many of which have survived, and a rebuilder of roads such as Via Trajana and Via Trajana Nova.

In 107, after returning from the East, he celebrated a triumph in Rome for his victories in Dacia and Arabia.

A notable act of Trajan's was to hold a three-month gladiator games in the great Colosseum in Rome, though the exact date is unknown. Combining chariot racing, animal fighting, and gladiator fights, this bloody spectacle was said to have left eleven thousand dead, mostly slaves and criminals, not to mention the thousands of ferocious beasts killed along with them. It drew a total of five million viewers during the games.

Another important act was his formal creation of Alimentas, a welfare program that helped orphaned and impoverished children throughout the Roman Empire. It provided general funds, as well as subsidized food and education. The program was initially supported by funds from the Dacian war, and later by a combination of state taxes and philanthropy. Thus, it favored the development of the birth rate, which had fallen to alarming rates, so that the risk was run. danger of a shortage of soldiers. On the arch of Benevento, the distribution of food among the population and especially to poor children is represented on the basis of the Institutio Alimentaria. Also in reliefs preserved in the Roman Forum reference is made to the institution of the Alimenta Italiae in favor of the pueri et puellae alimentarios.

This makes it clear that Trajan not only concentrated his energies and those of the Empire on military campaigns and the construction of public buildings. He was also a cautious statesman and philanthropist, interested in the conditions of his citizens and therefore attentive to social and political reforms. In judicial matters, he reduced the times of the processes, prohibited anonymous accusations, as well as convictions with a lack of solid evidence or in the presence of any doubt. In economic and social matters, he found a way to organize the bureaucracy and promulgated laws in favor of small peasant property, whose base was threatened by the expansion of the latifundio. Trajan favored the repopulation of free peasants in the peninsula, investing capital and providing the colonists with the means to support themselves and work in the fields; in exchange, the colonists invested a part of the crops as payment of the debt. This system, known as colonato, needed state control in order to function. On the one hand, it was necessary to prevent the tax collectors from preying on the settlers or the landowners from demanding more than they should, reducing the peasants to misery and semi-slavery; on the other, he needed to defend the settlers from bandits and invaders who could have devastated the land, forcing them to abandon the countryside and go to the city, leaving the land uncultivated. To avoid the decline of Italian agriculture, he imposed on the senators that they invest in Italy at least a third of their capital. He set limits to emigration from the peninsula, trying to encourage the presence of the business social class and the workforce in an Italy that was losing its centrality and was on the verge of heading into a phase of decadence. Trajan had the records of delayed taxes burned to alleviate the fiscal pressure on the provinces, an act that is represented in the so-called Plutei de Trajano of the Julia Curia. He abolished some taxes that charged both on the provincial and on the italics; he was thus able to create a type of popular savings bank that granted loans to small peasants and Roman businessmen who thus benefited from extensive concessions; This is how the first cooperatives and professional associations were favored.

With the profits and income from the reforms undertaken, Trajan built schools and orphanages for the illegitimate children and orphans of his soldiers, guaranteeing them a monthly subsidy and adequate instruction. By doing this, the emperor guaranteed succeeding emperors a skillful and capable ruling social class. Economic problems were solved on the battlefield, which had the double purpose of establishing peace on the borders and finding the gold and silver necessary for construction, reforms and to fill the economic deficit of the previous emperors. His successor, Hadrian, found herself in luck with an economically active empire.

His prolonged stays in the foreign war did not prevent Trajan from carrying out an intense internal policy, reason for warm praise in Roman historiography, spokesman for the opinion of the Senate, an ancient institution that brought together in its bosom the aristocracy and longed for the power he had enjoyed in the republican regime prior to the establishment of the Principality by Augustus.

Trajan's rise to power meant for the Senate the recovery of its lost freedom, “a new time”, says Pliny. With the collaboration of the Senate, where he established the secret vote, Trajan drew up a plan for moral and political regeneration that had consequences for the administration, justice, and economy.

The wars against the Parthians

In 113 Trajan began a campaign against the Parthians, sparked by the decision of the Parthian king Osroes to place an unacceptable puppet king on the throne of Armenia, a kingdom over which the two great empires had shared hegemony since the time of Nero some fifty years before. Probably, the idea of the emperor was also born from his desire to carry out the campaigns that Julius Caesar, his favorite author, had planned before he died: north of the Danube and against the Parthians.

The first phase was a complete success. The Parthians were defeated and Armenia, Assyria and Mesopotamia were integrated into the Empire. He began with Armenia, deposing its Parthian king, Partamasiris, in 114, and making Armenia a Roman province. He then marched south into Parthia itself, taking the cities of Babylon, Seleucia, and finally the capital Ctesiphon in 116. He continued south, reaching the Persian Gulf, lamenting that he was too old to follow in Alexander's footsteps. Great and reach distant India itself. It was the farthest eastern point that the Roman Empire reached. Not only was all of Mesopotamia occupied, but the vanguard of the Roman army, led by Lusio Quieto, peered over the first mountain ranges of Persia. With the new provinces of Mesopotamia and Assyria, the Empire reached its maximum extension, fixing its eastern border on the Tigris River and not, as until then, on the Euphrates.

Beyond these limits he could not continue, above all, due to logistical problems. The vastness of the occupied territories and the presence of sacks of resistance and the guerrilla tactics with archers on horseback, used by the Parthians, endangered the conquest. In 116, Trajan, aware of the difficulties, decided to take up the arms of politics, deposed the Parthian king Osroes I and placed his own puppet ruler, Partamaspates, on the throne. On the other hand, his health began to fail him. The fortress city of Hatra, with the Tigris to its rear, continued to hold out against repeated Roman assaults. He was personally present at the siege and may have suffered heat stroke in the high temperatures. Shortly thereafter, the Jews within the Roman Empire rose in rebellion once more, as did the people of Mesopotamia. The Jews revolted throughout the Near East: Egypt, Cyprus, Cyrenaica, Judea and Mesopotamia since the year 115, in the midst of a campaign against the Parthians, when the emperor was forced to withdraw his army to crush the revolts. He considered it merely a passing setback, but was destined never to command an army on the field of battle again, turning his eastern armies over to the high-ranking legate and governor of Judea, Lusius Quietus, who took charge along with Quintus. Marcio Turbon. Trajan's conquests grew the empire from 5 million km² to more than 6 million.

Later in 116, Trajan fell ill and started back to Italy. His health declined in the spring and summer of 117, and by the time he reached Selinus of Cilicia, which was later named Trajanopolis in his honor, he died suddenly of edema early in August. Trajan's ashes were placed under Trajan's Column, the monument that commemorated his success, repealing the old law that prevented burials inside the city's perimeter. The urn was lost during the barbarian invasions, and its trace was lost, presumably being melted down. Hadrian, upon becoming emperor, returned Mesopotamia to the Parthian Empire, as part of a peace treaty in 125, but retained the rest of the territories conquered by Trajan.

Succession

Just before he died, Trajan adopted Hadrian (Publius Aelius Hadrianus) as his successor. He was the son of a cousin of Trajan and was married to a great-niece of the emperor. He had also fought in the Dacian wars, where he had an outstanding participation. Roman historians picked up the rumor that it was his wife, Pompeii Plotina, who faked such an adoption, hiding a slave under the sheets of the dead emperor, who whispered the adoption as the dying man's presumed last will. However, it seems that he had already shown his preference for Hadrian as successor in previous years, from the year 100 or around the year 106, because although their relationships had suffered ups and downs, Hadrian was actually the only direct male relative. of Trajan and, therefore, the only possible heir for the continuation of a true dynasty.

Buildings

Trajan was a good patron, especially in the field of architecture, both in Italy and in the provinces, and many of his buildings were the work of the talented architect Apollodorus of Damascus. He carried out necessary constructions to facilitate the Romanization and improve the living conditions of the citizens. Thus, he reinforced the road network, restoring the main roads that expanded from the City, uniting it with the rest of the empire.

In addition, he built buildings that contributed to perpetuate his memory while seeking to beautify the City and increase the possibilities of entertainment for the Romans, such as theaters or circuses. Among the constructions he carried out are the famous hexagonal Port of Trajan in the Fiumicino area, whose remains are still impressive today. This new port at Ostia linked Rome with the western regions of the Empire. The work was among the most important for the city, which thus avoided its supply problems outside the already existing "Claudio port". He enlarged the port of Ancona with the construction of a pier to facilitate navigation towards the East, a pier that was decorated with an arch; he sought a new route of the Via Appia towards the port of Brindisi, which started from another arch built in Benevento. He also intervened in the Pontine Lagoons.

In the city of Rome he renovated the center of the city with the construction of an immense forum and the brick building adjoining it, intended for public administration, for which he had large areas of the surrounding hillsides leveled (Quirinal and Campidoglio). The extraordinary Trajan Forum complex solved the congestion problems in the center of the ancient city around the Via Sacra. the extraordinary dimensions of the work, also supervised by Apollodorus, were such that they surpassed in grandeur that of all the other forums combined. In addition to the public Ulpia basilica, the square, the colonnade, the offices, the libraries and the temple of the divine Trajan, he erected Trajan's Column in its forum as a celebration of his military conquests in the Dacia campaign, still today one of the symbols of the eternity of Rome. It is about 30 meters high and 4 meters wide, originally it was colored; inside it has a spiral staircase that leads to the top. Outside, a spiral develops on the column, with a 200-meter-long mosaic that houses more than 2,000 figures sculpted in bas-relief. The column was crowned by a statue of the emperor, which was replaced in 1588 by one of Saint Peter, and at the base was placed the gold funerary urn containing the ashes of the late emperor who thus received the exceptional honor of being buried. inside the pomerium, that is, the city walls. The gold urn was taken by the Visigoths in the sack of Rome (410) and its trace was lost.

Trajan is responsible for the construction of another aqueduct that further increased Rome's water resources, which were already abundantly assured by the aqueducts built previously and above all by the so-called Anio Novus built under the emperor Claudius. The work began in the year 109, collecting the structure, water that arose in the Sabatinos mountains, near the lake of Bracciano (lacus Sabatinus). The total length was about 57 kilometers and it carried about 2848 quinarie daily, that is, a little more than 118,000 m³. It reached the city after a largely underground route along the Via Clodia and Via Triunfal and then its arches along the Via Aurelia. It reached Rome on the Janiculum hill, on the right bank of the Tiber river. The extension of the water network was encouraged not only in Rome, but also in Dalmatia, in his native Spain and in the East, that is, in arid climates that required a greater supply of water. In Rome, Trajan had the underground channels and drains of the Cloaca Maxima widened so that rainwater and those that ended up discharging into the Tiber ran more efficiently. The banks of the river were also reinforced to prevent overflows that would affect the city. For the leisure and pleasure of the common people, he had some works carried out that gave Rome the appearance that, roughly speaking, everyone has in the common imagination of the city. He had the Circus Maximus reconstructed and enlarged definitively, of which the first three rings at the base of the structure were erected with calcestruzzo and covered with mattoni and marbles, only the upper ring remained in wood; the structure thus became safe and fire-resistant, and favored the construction of workshops and businesses on its sides. On Oppio Hill he had a great baths erected over the remains of Nero's Domus Aurea; It was accessed by a large propylaeus that led directly to the natatio, the open-air pool. On the right bank of the Tiber, where the current Castel Sant'Angelo stands, he built an area for the naumaquias, that is, reproductions of naval battles. The building efforts of the emperor were not concentrated only in the capital but in the entire empire.

In Egypt he joined the Nile to the Red Sea with a large canal (the Trajan River). He founded many colonies on all sides of the Empire. In Dacia, after having subjugated it, he favored the colonization and founding of new colonies that quickly romanized the province. The Colonia Ulpia Traiana arose on the ashes of the barbaric Sarmizegetusa Regia. He built bridges, including the longest (1,135 m) over the Danube near Drobeta. It served a double purpose: on the one hand, it guaranteed a supply route for the legions and, on the other, it impressed and discouraged the enemies by being a demonstration of technological, logistical, and military superiority. He also built several in Hispania, among which the bridge near Alcántara over the Tagus River stands out; others would be the Roman bridge of Salamanca and, possibly, the bridges of Alconétar and Bibey.

In 2009, a monument to the emperor was discovered in the province of Caraş-Severin (Romania).

Legacy

Unlike other esteemed rulers throughout history, Trajan's reputation has endured undiminished for nearly two thousand years, to the present day. Trajan was remembered by his contemporaries as one of the greatest emperors, comparable only to Augustus. He was given the title of Optimus Princeps ( the best of princes ) by the Senate, both for his conquests and constructions throughout the years. the entire Empire and the good treatment he had with the senators.

In later centuries, both in the Roman Empire and during a good part of the Byzantine Empire, every time an emperor ascended the throne, the Senate always expressed the following wish: Felicior Augusto Melior Traiano. That is to say, "that he is more fortunate than Augustus and better than Trajan", because both princes symbolized the summits of the imperial stage.

The Christianization of Rome resulted in an even further embellishment of his legend: Pope Gregory I was said in medieval times, through divine intercession, to have raised Trajan from the dead and baptized him in the Christian faith, but Saint Matilde of Hackeborn, in her: Book of Special Grace, 5th part, Chap. XVI: "Of the souls of Solomon, Samson, Origen and Trajan" notes:

"In prayers of a religious question to the Lord where are the souls of Samson, Solomon, Origen and Trajan; and the Lord says to him, "I want men to remain hidden from the provisions of my piety for Solomon's soul, so that they may avoid carnal sins more carefully. And it is also my will not be known the decisions of my Pity with the soul of Samson so that the mortals will tremble their instincts of vengeance in their enemies; and I also want to ignore what has done my will with the soul of Origen so that no one dares to be intonated trust of his science (*); and equally I decided not to know man the glorification of my Catholic soul ♪

In the Saint Gallen manuscript, the following is noted —although in the margin—: «I want the provisions of my goodness towards Aristotle to be hidden lest the philosopher emphasize the sole nature, despising the supernatural and heavenly things» (edition of the Monastery of San Benito, Buenos Aires, 1942, pp. 342-343).

An account of this fact by Gregory I appears in the Golden Legend. Among medieval Christian theologians, such as Thomas Aquinas, he was considered an example of a virtuous pagan. In the Divine Comedy, Dante, following this legend, sees the spirit of Trajan in the Heaven of Jupiter with other historical and mythological people noted for their justice, among the six just spirits that form the eagle's eye mysticism. Also featured in Piers Plowman. Several works of art reflect the episode known as Trajan's justice. The anecdote refers to a widow who stopped him while he was on his way to the Dacia campaign. She is she stopped him with her crying, begging him to grant her justice by finding and justly punishing the culprit of the death of her son. Trajan assured her that she would take up her case upon her return. The widow then reminded him that she might not return, so Trajan assured her that in such a case she would act as her heir in her place. Then the widow pointed out that in that case she would not have kept her promise, because then the case would not have been resolved by him and, even if he obtained justice, it would not be on his merit. So Trajan dismounted, sought out and punished the culprit, granted justice to the widow, and marched to war.

To be closer to the Roman people, Trajan had the writing on the door of his residence: Palazzo Pubblico, so that everyone could enter it freely. He used to receive, personally and without an appointment, anyone who wanted to get justice from him. From which derives another famous anecdote: in response to the protests of his secretary, who complained that his lord was trusting everyone incautiously, Trajan replied: "I treat everyone as I would like the Emperor to treat me, if I were a private citizen".

The 18th century historian Edward Gibbon listed Trajan among the five emperors who ruled the vast territory of the Roman Empire « by absolute power, guided by virtue and wisdom", considering that

If anyone was asked to determine the period of the history of the world in which the human condition was more prosperous and happy, he would certainly mention the one that spreads between the death of Domitian to the ascent of Comfort.

"Traian" is used as a given name in present-day Romania. Among others, President Traian Băsescu has it. In the Romanian national anthem, Deşteaptă-te, române!, Trajan is evoked in the second verse:

- Şi că-n a noastre piepturi păstrăm cu fală-un nume

- Triumfător în lupte, a nume de Traian!

The translation from Romanian to Spanish reads:

- And that in our hearts we proudly keep a name

- Triumphant in battles, Trajan's name!

Imperial title

Over the years, he obtained the following honors and positions:

- the title Pater Patriae 98 and 98 Optimus princeps 114;

- the victorious titles of Germanicus in October 97, Dacicus in 102 and Parthicus in 116;

- acclaim as Imperator 13 times: I (?), II 101, III and IV 102, V and VI 106, VII and VIII 114, IX, X and XI 115, XIII 116;

- the consulate six times in the years 91, 98, 100, 101, 103 and 112;

- the Tribunicia Potestassthe first (I) on 27 October 97, the second (II) on 28 January 98, the third (III) on 10 December 98, then renewed annually every 10 December until the twenty-first (XXI) in the year 116.

Contenido relacionado

Labyrinth

Chichimeca

Hyperinflation