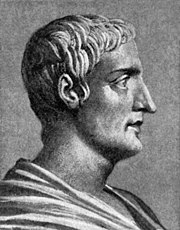

Tiberius

Tiberius Julius Caesar Augustus (Latin: Tiberius Iulius Caesar Augustus; Rome, November 16, 42 BC-Misenum, March 16, 37 AD) was the second Roman emperor, ruling from September 17, AD 14 until his death.

He was the son of Tiberius Claudius Nero and Livia Drusilla, therefore a member of the Claudian gens. His family became related to the imperial family when his mother divorced her father and she married Octavian Augustus (39 BC). After this marriage, Tiberius married Augustus's daughter, Julia the Elder. He was formally adopted by Augustus on June 26, AD 4, becoming part of the gens Julia. Upon his adoption, he was granted tribunician powers for ten years.

As tribune, he reorganized the army again, reforming military law and creating new legions. The time in ranks amounted to twenty years, except for the Praetorians or Imperial Guard, set at 16 years. After completing the time of service, the soldiers received a salary whose amount came from a 5% tax on inheritances. Later Tiberius fell out with the Emperor Augustus, and was forced into exile in Rhodes. However, after the death of Augustus's eldest grandsons and foreseeable heirs of the Empire, Gaius Caesar and Lucius Julius Caesar, linked to the treasonous banishment of his youngest grandson, Agrippa Posthumus, he was recalled by the emperor and appointed successor. In the year 13 the powers of Augustus and Tiberius were extended for ten years. However, Augustus died soon after (August 19, 14), leaving Tiberius as sole heir. Upon his enthronement, all powers were transferred to Tiberius without any deadline.

Tiberius was in his youth one of the greatest generals in Rome. In his campaigns in Pannonia, Illyricum, Rhaetia, and Germania, he laid the foundations of what would later become the northern frontier of the Empire. However, he was later remembered as a dark, reclusive and shadowy ruler, who never really wanted to be emperor; Pliny the Elder called him tristissimus hominum ("the saddest of men"). After the death in AD 23 of his beloved son and successor, Drusus the Younger, the quality of his rule declined. and his reign ended in terror. In 26 Tiberius self-exiled from Rome and left the administration in the hands of his two Praetorian prefects Sejanus and Quintus Nevio Cordo Sutorio Macron. In 35, he targeted Caligula and Tiberius Twin as his successors.

Youth

Origins

Tiberius was born in Rome on November 16, 42 B.C. C. of the father of the same name Tiberio Claudio Nero, Caesarian, praetor during that same year, and of Livia Drusilla, some thirty years younger than her husband. Both the paternal and maternal branches belonged to the Claudian gens, an ancient patrician family that came to Rome from Sabinia in the early years of the republic and distinguished itself through the centuries by the achievement of numerous honors and high magistrates.. From the beginning, the gens Claudia was divided into numerous families, among which the one that assumed the cognomen Nero (Nero, which in the Sabine language means & #34;strong and brave"), to which Tiberius belonged.

He was therefore a member of a lineage that had given birth to prominent personalities, such as Appius Claudius the Blind, and ranked among the greatest advocates of the superiority of the patriciate. His father had been among the most ardent supporters of Gaius Julius Caesar and, after his death, sided with Marco Antony, Caesar's lieutenant in Gaul, coming into conflict with Octavian, Caesar's designated heir.

After the constitution of the Second Triumvirate between Octavian, Antony and Lepidus and the consequent proscriptions, the contrasts between Octavian's supporters and those of Antony materialized in a situation of conflict, but Tiberio's father continued to support the former lieutenant of Caesar. At the outbreak of the Perusian War, awakened by the consul Lucio Antonio and Fulvia, wife of Marco Antonio, Tiberio's father joined the Antonians, fomenting the discontent that was emerging in many regions of Italy. After the victory of Octavio, who managed to defeat Fulvia, he entrenched himself in Perugia and to restore his control over the whole of the Italian peninsula, he was forced to flee, taking his wife and son with him. The family took refuge in Naples and then went to Sicily, controlled by Sextus Pompey. The three were forced to reach Achaia, where Antony's troops who had left Italy were meeting.

Little Tiberio, forced to participate in the escape and suffer the insecurities of the trip, had an uncomfortable and troubled childhood, until the Brindisi agreements, which restored a precarious peace, allowed the Antonians to return to Italy.

In 39 B.C. C., Octavio decided to divorce his wife Escribonia, from whom he had his daughter Julia, to marry little Tiberio's mother, Livia Drusilla, with whom he was truly in love. However, the wedding had important political significance: Octavian hoped to be able to draw closer to the Antonian faction, while Tiberius's aged father intended, by giving his wife to Octavian, to further distance his rival from Sextus Pompey, that he was Scribonia's uncle.

The triumvirate requested permission from the College of Pontiffs for the wedding, since Livia already had a son and was expecting a second. The priests consented to the marriage between the two, placing the paternity of the fetus as the only clause. Therefore, on January 17, 38 B.C. C., Octavio married Livia, who after three months gave birth to a son who was named Drusus. The question of paternity, in fact, remained uncertain: some claimed that Drusus was born from an adulterous relationship between Livia and Octavio, while others praised the fact that the newborn had been generated in the ninety days between the marriage and their marriage. Later, it was possible to determine how Drusus's paternity was owed to Tiberius's father, as Livia and Octavian had not yet been reunited when the child was conceived.

While Drusus was raised by his mother in Octavian's household, Tiberius remained with his aged father until the age of nine: in 33 B.C. C., the latter died and it was the very young son who pronounced the laudatio funebris from the Rostra of the Forum. Tiberius immediately moved into Octavio's house together with his mother and brother, just when the tensions between Octavio and Antonio gave rise to a new conflict, which ended in 31 BC. C. with the decisive battle of Actium. In 29 a. C., during Octavio's triumph ceremony after the final victory over Antonio in Actium, it was Tiberius who preceded the victor's chariot, leading the inner horse on the left, while Marcelo, Octavio's nephew, rode the outer one to the right, thus being in honor. Later he also directed urban games and participated in the Trojans, which were held in the circus, as head of the older children's team.

At the age of fifteen, he was dressed in a manly toga, thus beginning in civilian life: he distinguished himself as defender and prosecutor in numerous trials and simultaneously dedicated himself to learning military art, standing out in particular for his abilities to mount. He also devoted himself, with great interest, to the studies of Latin oratory, Greek rhetoric, and law; he frequented the cultural circles linked to Augustus, where he spoke both Greek and Latin: therefore, he met Gaius Maecenas and the artists he financed, such as Quintus Horacio Flacco, Publius Virgilio Marón and Sextus Propertius. He dedicated himself with equal passion to the composition of poetic texts, imitating the Greek poet Euphorion of Chalcis, on mythological themes, in a tortuous and archaic style, with great use of rare and obsolete words.

Civil and military career (25-6 BC)

If Tiberius owed much of his political rise to his mother Livia Drusilla, Augustus's third wife, his military skills as a commander and strategist remain unquestionable: he remained undefeated during all his long and frequent campaigns, so much so that in the Over the years, he was one of his stepfather's best lieutenants.

Tasks in Spain and the East (25-16 BC)

Given the lack of true military schools that would allow them to gain experience, in 25 B.C. C., Augusto decided to send Tiberio and Marcelo, sixteen years old, to Hispania as military tribunes. There, the two young men, whom Augusto saw as his possible successors, participated in the initial phases of the Cantabrian Wars, started by the Augustus himself in the previous year and finished, in 19 B.C. C., by general Marco Vipsanio Agrippa.

A year later, in the year 24 B.C. In BC, at the age of eighteen or nineteen, Tiberius was appointed Quaestor of the Annona, five years earlier than stipulated by the traditional cursus honorum of magistrates. It was a particularly delicate task., which consisted mainly of guaranteeing the supply of wheat for the entire city of Rome, which at that time had more than a million inhabitants, two hundred thousand of whom could only survive thanks to the free distribution of wheat by the state; In addition, in that period the City also had to go through a period of famine due to a flood in the Tiber that had destroyed most of the crops in the Lazio countryside, preventing even ships with supplies on land from reaching Rome with their supplies. food products.

Tiberius coped vigorously: he bought the grain that the speculators stored in their warehouses at his own expense and distributed it free of charge, in order to be considered a benefactor of Rome. Therefore, he was accused of carrying out inspections in the ergastulas, underground prisons in which slaves, travelers and those seeking refuge to avoid military service were locked up. This time, this was not a particularly prestigious task, but equally delicate, as that the owners of the ergastula had become hateful to the entire population of Italy, thus creating a situation of tension.

In the winter from 21-20 a.m. In BC Augustus ordered Tiberius to lead a legionary army, recruited from Macedonia and Illyria, eastwards towards Armenia. This was a region of fundamental importance for the political balance of the entire eastern area: it played a buffer role between the the Roman Empire to the west and the Parthian Empire to the east, and both wanted it to be theirs. It had been a vassal state, guaranteeing the protection of its borders from enemies. But after the defeat of Mark Antony and the fall of the system he had imposed in the east, Armenia had returned under the influence of the Parthians, who favored the accession to the throne of Artaxias II. Augustus therefore ordered Tiberius to expel Artaxias, whom the philo-Roman Armenians demanded the deposition, and to impose on his throne his younger brother Tigranes, of pro-Roman leanings.

The Parthians, frightened by the advance of the Roman legions, made concessions and signed a peace with Augustus himself –who had meanwhile reached Samo in the east–, returning the banner and the prisoners they had taken after the victory on Marco Licinio Crassus in the Battle of Carras of 53 BC. In this way, the Armenian situation was resolved even before the arrival of Tiberius and his army thanks to the peace treaty between Augustus and the Parthian sovereign Phraates IV: the pro-Roman party was able to take control and some agents sent by Augustus they eliminated Artaxias. Therefore, upon his arrival, Tiberius had no further task than to crown Tigranes, who took the name Tigranes III, as a client king, in a peaceful and solemn ceremony held before the eyes of the Roman legions.

Upon his return to Rome, the young general was celebrated with great parties and the construction of monuments in his honour, while Ovid, Horace and Propertius wrote compositions in verse to celebrate his feat. However, the credit for the victory corresponded to Augustus, as commander-in-chief of the army: in fact he was proclaimed imperator for the ninth time, he was able to announce in the Senate the vassalage of Armenia without decreeing the annexation and finally wrote in his Res gestae Divi Augusti: "Though I was able to make Greater Armenia a province after the assassination of its king Artaxias, I preferred, following the example of our ancestors, to entrust that kingdom to Tigranes, son of King Artavasides and nephew of King Tigranes, through Tiberius Nero, who was then my stepson". In the year 19 a. C., the rank of former praetor, with the ornamenta praetoria , was conferred on Tiberius, and therefore, he could sit in the Senate, among the former praetors.

Recia, Illyria and Germania (16-7 BC)

Recia and Vindelicia

Although Augustus, after the campaign in the east, had officially declared in the Senate that he would abandon the policy of expansion, knowing that an excessive territorial extension would have been lethal for the Roman empire, nevertheless he decided to implement other campaigns to ensure the borders. In 16 a. C., Tiberio, newly appointed praetor, accompanied Augusto to Gaul Comata, where he spent the next three years, until 13 a. C., to help him in the organization and government of the Gallic provinces. The princeps was also accompanied by his stepson on a punitive campaign across the Rhine against the Sicambrian tribes and their allies, the Tencterians and Usipeters, in the winter of 17-16 BC. C. that had caused the defeat of the proconsul Marco Lolio and the partial destruction of the Legio V Alaudae and the loss of legionary standards.

In 15 a. In BC, Tiberius, together with his brother Drusus, led a campaign against the Reti, a tribe established between Noricum and Gaul, and the Vindelics. Drusus had previously expelled the Reti, who had been guilty of numerous crimes, from Italian territory. raids, but Augustus decided to send Tiberius to resolve the situation for good. which they also put into practice thanks to the help of their lieutenants: Tiberius marched from Helvetia, while his younger brother marched from Aquileia and Tridentum, along the Adige and Isarco valleys, at the confluence of which they built the Pons Drusi, near present-day Bolzano, and finally ascending the Eno river.

Tiberius, advancing from the west, defeated the Vindelics near Basel and Lake Constance; in that place the two armies could meet and prepare to invade Bavaria. Joint action allowed the two brothers to advance to the source of the Danube, where they won the last and final victory over the Vindelics. These successes allowed Augustus to subjugate the populations of the Alpine arc as far as the Danube, and earned him new acclaim from imperium, while Drusus, Augustus' favorite stepson, for this and other victories, was later able to score a triumph. On a mountain near the Principality of Monaco, near present-day La Turbie, the Trophy of Augustus was erected, to commemorate the pacification of the Alps from one end to the other and to remember the names of all submissive tribes.

Illyria, Macedonia and Thrace

In 13 a. C., having gained the reputation of an excellent commander, he was appointed consul and was sent by Augustus to Illyria: the brave Agrippa, in fact, who had fought against the rebellious populations of Pannonia, died as soon as he returned to Italy. The news of the general's death caused a new wave of rebellions among the peoples defeated by Agrippa, particularly Dalmatians and Breucans, for which Augustus assigned his stepson the task of suppressing them.

Tiberius, after assuming command of the army in 12 B.C. C., defeated the enemy forces and implemented a policy of harsh repression against the defeated; Thanks to his strategic capacity and the cunning that he demonstrated, he was able to achieve a total victory in just four years, with the help of general experts such as Marco Vinicio, governor of Macedonia, and Lucio Calpurnio Piso. In the year 12 B.C. C. subdued the Breucos, taking advantage of the help provided by the Scordisci tribe, subdued shortly before by the proconsul Marco Vinicio: he deprived his enemies of weapons and sold most of their young people as slaves, after having deported them, and obtained the ornamenta triumphalia from Augustus. At the same time, along the eastern front, the governor of Galatia and Pamphylia Lucius Calpurnius Piso had been forced to intervene in Thrace, as the locals, particularly the Bessi, threatened the Thracian king Remetalce I, an ally of Thrace. Rome.

On 11 a.m. C. saw Tiberius face first against the Dalmatians, who had rebelled again, and shortly after against the Pannonians who had taken advantage of his absence to conspire again. Therefore, the young general was heavily engaged in simultaneously fighting several enemy towns and was forced to move from one front to another several times. In the 10 a. C., the Dacians crossed the Danube and carried out serious raids on the territories of Pannonia and Dalmatia. The latter, therefore, also harassed by the taxes imposed by Rome, rebelled again. Tiberius, who had gone to Gaul together with Augustus earlier in the year, was forced to return to the Illyrian front to face and defeat them once more. At the end of the year, he was finally able to return to Rome with his brother Drusus and Augustus.

Once the long campaign was over, even Dalmatia, now definitively incorporated into the Roman state and begun in the process of Romanization, was entrusted as the imperial province to the direct control of Augustus: in fact, an army needed to be permanently assigned ready to repel possible attacks along the border and to suppress possible new revolts. Augustus, however, at first avoided formalizing the salutatio imperative that the legionaries had bestowed on Tiberius and refused to pay homage to the stepson at the triumph ceremony, contrary to the opinion expressed by the Senate.

In any case, Tiberius was allowed to travel the Via Sacra in a chariot decorated with triumphal regalia and celebrate an ovatio: it was an entirely new use that, although inferior to the triumph celebration in yes, it was, however, a remarkable honor. In the 9 a. C., Tiberio was dedicated entirely to the reorganization of the new province of Illyricum. While from Rome, where he had celebrated his victorious campaign, he returned to the eastern frontiers, Tiberius was warned that his brother Drusus, while on the banks of the Elbe fighting the Germanic peoples, had fallen from his horse and fractured himself. The femur.

The incident seemed trivial and was therefore neglected; Drusus's condition, however, suddenly deteriorated in September. Tiberius joined him at Mogontiacum to give him comfort as he had traveled over two hundred miles in one day. Drusus, upon the news of his brother's arrival, ordered the legions to receive him with dignity, and later expired in his arms. Therefore, it was Tiberius himself who led the funeral procession that carried Drusus's body to Rome, ahead of everyone on foot. In Rome, he delivered a laudatio funebris for his deceased brother in the Forum, while Augustus delivered his in the Circus Flaminius; Drusus's body was then cremated on the Campus Martius and the ashes deposited in the Mausoleum of Augustus.

Germany

In the years 8 and 7 B.C. C., Tiberius was sent back to Germany, to continue the work started by his brother Drusus and fight against the Germanic peoples, after his premature death. Thus, he crossed the Rhine, and the tribes frightened of the barbarians, with the exception of the Sicambrians, put forward proposals for peace, but, nevertheless, received a clear refusal, since it would have been useless to conclude a peace without the accession of the dangerous sycambria; When they also sent men, Tiberius had them massacred and deported. Due to the results obtained in Germany, Tiberius and Augustus again obtained acclamation as imperator and Tiberius was appointed consul for 7 BC. In this way he was able to complete the job of consolidating Roman power over the region by building numerous fortresses, including Oberraden and Haltern, and thus extending Roman influence to the River Weser.

Retreat in Rhodes

In 6 a. C., when he was about to assume command of the East and thereby become the second most powerful man in Rome, he announced that he was abandoning political life and retired to Rhodes. The reasons for this sudden withdrawal are unclear. Ancient historians have speculated that Tiberius felt like a stopgap when Augustus adopted Julia and Agrippa's sons Gaius Caesar and Lucius Caesar and favored them throughout his life. his career as he had done with Drusus and with Tiberius himself. The future emperor could have thought that when his stepsons came of age they would replace him without consideration and he felt used. The well-known promiscuous behavior of his wife could also play a role. According to Tacitus, Tiberius retired to Rhodes for personal reasons, where he began to hate his wife and long for his ex-wife Vipsania. Tiberius was married to a woman that he hated, that he humiliated him with his public nocturnal escapades in which he starred, and that he had forbidden him to see the woman he loved.

Regardless of Tiberius' motives, the withdrawal was disastrous for Augustus' succession plans. Gaius and Lucius were still in their teens, and Augustus, then 57 years old, did not have an immediate successor. The withdrawal of Tiberius endangered a peaceful transfer of power after the death of Augustus and ceased to be a guarantee that after the death of the Prince (princeps), power would remain in the hands of his family or of his family's allies.

Certain apocryphal stories relate that when Augustus fell seriously ill, Tiberius sailed for Rome and landed in Ostia learning that Augustus had survived. Tiberius returned to Rhodes and from there sent letters to the emperor requesting him to return to Rome, which Augustus told him. denied on several occasions.

Heir to the Throne

With the retirement of Tiberius, the succession fell exclusively to Augustus's two young grandsons, Gaius and Lucius Caesar. The situation suddenly became more precarious with the death of Lucio in 2 d. Augustus, at Livia's request, allowed Tiberius to return to Rome as a Roman citizen and nothing more. In 4, Gaius died in Armenia and Augustus had no choice but to turn to Tiberius.

The death of Gaius in 4 began a frenzy of activity in the palace. Tiberius was adopted as a full son and heir. In turn, Tiberius was forced to adopt his nephew, Germanicus, the son of his brother Drusus the Greater and Antonia the Lesser (Antonia Minor). Tiberius received tribunician powers and assumed part of the maius imperium of Augustus, something even Agrippa had not been rewarded with. In 7, Agrippa Postumus was disowned by Augustus and went into exile on the island of Pianosa, where he lived in solitary confinement. In 13, the powers of Tiberius they were equaled to those of Augustus himself. Tiberius became co-princeps with full rights, and in the event of Augustus's death he only had to succeed him normally.

Augustus died at 14, at the age of 76. Augustus was buried with all the ceremonies established beforehand and was deified through the new rite of apotheosis, which his successors will inherit. Tiberius on his part was confirmed as sole successor.

Emperor

First stage

Consistent with Augustus's method and the appearances he had initially made before the Senate, Tiberius was careful not to be exposed by the extent of his personal power. He decided not to adopt the name Imperator: he only added the epithet of Augustus to the name of Tiberius Julius Caesar which was his since his adoption; and, in inscriptions and coins, the name Tiberius Caesar Augustus succeeded that of Imperator Caesar Augustus. He never allowed himself to be awarded the title of father of the country.

But, behind this apparently scrupulous attitude, he actually distanced himself more and more from the republican institutions. Tiberius decided to transfer the appointment of the magistrates of the Comitia to the Senate. With this, the Elections lost a very important attribution, and the Republic's own electoral system disappeared. Curiously, ending this right of citizenship was not difficult for him. In reality, the popular assemblies had been discredited for a long time, since they had shown themselves capricious, servile and incapable of making decisions, then they had ceased to be the representation of the Roman people.

The emperor designated candidates for some of the magistracies, and the places that remained vacant, without a proposal from the emperor, were designated by the Senate and a single list was formed. The Popular Assembly or Elections, which continued to be held until the 3rd century, limited itself to acclaiming the single list. The laws were promulgated without the intervention of the Assemblies. In fact, the people only retained power in one aspect: their favor or hostility were decisive for the emperors, and they were expressed in the great circus celebrations.

These measures seemed to strengthen the power of the Senate. But Tiberius procured a series of compensations. The most important was to increase the body of the Praetorian Guard from three cohorts to nine and the construction of a permanent camp for them called castra praetoria in a suburb of the city.

The Senate enacted several laws, including one on the social status of women who had sexual relations with slaves, one on guardianship, one on penalties for damage to public buildings, rules on criminal prosecution, punishment of slaves who were present in a house when the master was murdered, and a law of inheritance for women, whose sons had precedence over their brothers or relatives.

The Senate acquired an important function with respect to the provinces: the performance of senators as jurors in cases of concussion (Repetundae), that is, of illegal acquisitions by provincial governors and officials and, apparently, the Repetundis trials were frequent. He also tried the crimes of treason or lèse majesté.

A law, the Lex de Maiestate, promulgated the previous century, regulated the sentences for offenses against the highest dignitaries of the Empire, and Tiberius had to use it.

The category of senators could be accessed by those who owned land worth at least one million sesterces, a large part of which came from the class of knights. Thus, the majority of those who had the category of senators, although not all held the position, which was elected, constituted a hereditary caste that could only be accessed from other classes by direct or indirect imperial designation.

Institutionalization of positions

To become a senator, one had to previously exercise the following magistratures:

- The vigintivirate (veinte personas cada año), which was accessed from the age of eighteen, and which were superintendents for the rents of the cecas (currency houses) and other functions.

- The military rostrum.

- The quantum (see annual qualifiers), which was accessed from the twenty-five years, and which helped the provincial proconsuls or governors in matters of finance.

- The tribune of the plebe (debted each year), which was accessed at the age of 27 or 28, with the right to veto in certain public affairs. This Magistrate was emptied of political content with the consequent loss of power of the assemblies that presided over the tribune of the plebe.

- The preture (ten annual pretores, increased after eighteen), which was accessed at the age of thirty, and which was the government of a second order province and the command of a legion (propretores), or the development of a special preture (of the Erarium, etc.). They had judicial functions and appointed arbitrators in civil cases.

- The consulate (two ordinary consuls and other substitutes), which was accessed from the forty years. The functions of the consul were to preside over the Senate and the Assemblies and, in some cases, administer justice.

- Proconsules or provincial governors, who governed the first-order Senate provinces, with consular powers (civic-military).

After exercising all or part of these magistracies, the rank of senator was reached. Most of the senators were Italian, coming from the senatorial class.

Rights and functions of the emperor

The Imperator or Princeps had all the powers of a tribune (Tribunicia potestas), of which he had a proconsul in the government of the provinces, power that the Imperator could exercise in any part of the territory, and surely of the powers of a consul, since if he wished he held the position of Consul ordinarius. He was also Pontifex Maximus and often also exercised censorial functions, although he did not hold the title of censor, a magistracy "resurrected" by Claudius. Several qualifications were attributed to him: Pater Patriae, Princeps Senatus, Imperator and Augustus.

The Imperator had the following officials at his service:

- Lictors (assistants or escorts).

- Pretorians, regrouped military units in a special unit to the imperial service, which served at headquarters or Pretorios. They constituted the personal guard Imperator and had the front Praefectus Praetorius, In Tiberius' time he held this post, Sejano, who was then his minister.

- Them Speculator, cavalry body with escort and courier functions, although later in the centuryIIthe escort functions went to the Unique Equites Augusti, and the Frumentariiwhich performed the functions of messaging and spying and imperial police.

- Employees, slaves and imperial liberties, made up of thousands of different people of these conditions, who performed the domestic and service tasks of the imperial residences, being the most influential position of the Cubicularius (Champagne).

The emperor disposed of the following income, which constituted the Fiscus:

- Those from your personal properties.

- The legacies and heritages of citizens, which was first a custom, but which with some emperors led to an obligation.

- The war booty.

- The gold offered by cities and provinces.

- Probably a part of the property without heirs that were shared with the Aerarium (public finances).

The emperor's properties—land, palaces, villas in Italy or in the provinces, and others—seem to have passed to his successor, even if they were not related. Citizens and communities could go to the Imperator, ask him legal questions and receive an answer. In the time of Tiberius, the tributes to the provinces were exacted in moderation and the laws were justly applied.

The emperor also acted as censor, and commissioned the provinces to carry out the census, already instituted by Augustus. Among the laws that he applied, we will point out the following:

- Limit of spending on games and shows.

- Limit in luxury furniture.

- Annual senate fixation of food items.

- Order that established that the agaps had to be consumed integers, and forced the meat and other leftover foods to be consumed in later meals because it was customary to throw up half of an animal that had already eaten a part.

- It prohibited the habit of kissing every day.

- It did not delay beyond the January snacks the gifts from the beginning of the year.

- A family council would punish adulteres who had no public accuser.

- It prohibited the judges to acquire a woman by lot and then repudiate her.

- It prohibited the Egyptian rites and the Jews, and this last religion penetrated among the liberties.

- He established the Pretorian Cohorts or Imperial Guard, which were cantonated until that time in several places in Italy, in Rome.

The Rise and Fall of Germanicus

Military problems, for their part, quickly arose for Tiberius: the legions of Pannonia and Germania had not received the bonuses that had been promised to them during the reign of Augustus and after a brief period of time in which they assumed that there would be no answer for part of Tiberius, mutinied. Germanicus and Tiberius's son Drusus the Younger were sent to the region at the head of a force with the goal of putting down the rebellion and bringing the rebel legions back into ranks.

Germanicus, however, rallied the mutineers and led them on a brief campaign along the Rhine into Germanic territory, claiming that any loot they could get would constitute the promised cousin. Germanicus and his army crossed the Rhine and occupied all the territory between that river and the Elbe. Tacitus writes that Germanicus recovered the eagles that had been lost after the ignominious defeat at the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest, in which three Roman legions under Publius Quintilius Varus were annihilated in a German ambush. Despite the military indolence of Tacitus Tiberius, Germanicus had dealt a heavy blow to the enemies of Rome in Germany, had put down a mutiny of troops and had also brought to Rome the lost eagles. These heroic actions placed Germanicus in a privileged place in the line of succession.

Following his campaign in Germania, Germanicus celebrated a triumph in Rome in 17. This triumph was the first to behold the city of Rome since those of Emperor Augustus in 29 BC. C. In 18 the eastern provinces of the Empire were granted to Germanicus, as had been done with Agrippa and with Tiberius himself. This appointment meant that Germanicus was the clear favorite to succeed Tiberius. Germanicus died the following year, probably poisoned by the governor of the Syrian province, Gnaeus Calpurnius Piso. The Pisons had been supporters of the Claudians and had allied with the young Octavio after his marriage to Livia, the mother of Tiberius; therefore the emperor was suspect. At the trial, Piso threatened to implicate Tiberius, although it is not known for sure whether the governor of Syria would actually have been able to implicate the emperor. When a hostile attitude against Piso became general in the Senate, he committed suicide.

Tiberius for his part seemed to be tired of politics. In 22 he began to share tribunal powers with his son Drusus the Younger and began making excursions to Campania that became longer each year. In 23, Tiberius' son died under mysterious circumstances and Tiberius decided to retire to the island of Capri (26).

Tiberius in Capri, Sejanus in Rome

Sejanus had served the imperial family for more than twenty years when he was elected praetorian prefect in 15. As Tiberius grew loathing his position in power, he came to rely more heavily on the Praetorian Guard and its Sejanus leader. In 17/18 Tiberius delegated to the Praetorian Guard the task of defending the city, moving them to camps outside the city walls, thereby giving Sejanus command of between 6,000 and 9,000 soldiers. Drusus's death elevated Sejanus in the eyes of Tiberius who referred to him as "my companion." Tiberius erected statues of Sejanus throughout the city and gradually withdrew from power which was ceded to Sejanus. When Tiberius finally retired in 26, Sejanus was in charge of the administration of the state and the capital.

Sejanus's position was not exactly that of a successor, as he had asked for the hand of Livilla, Tiberius's niece in 25, and had been forced to withdraw the request under pressure. Sejanus and the guard controlled the imperial mail and therefore they were in possession of all the information that Tiberius sent to Rome and that Rome sent to Tiberius. Despite all the accumulated power, the presence of Livia Drusilla limited the area of action of the Praetorians, however, his death in 29 changed everything. Sejanus initiated a series of rigged trials of senators and wealthy knights from the Ordo Equester, eliminating all their political rivals and increasing the public treasury (and his own). own). Germanicus's widow, Agrippina the eldest, and two of his sons, Nero Caesar and Drusus Caesar, were arrested and exiled in 30, later dying under suspicious circumstances.

In 31, Sejanus held the consulship with Tiberius in absentia, thus beginning to seriously consolidate his power. What happened around this time is difficult to determine, although it seems that Sejanus tried to ingratiate himself with the families belonging to the Julio-Claudian dynasty with a view to being able to be adopted into the Julia family, occupying with it the position of regent or even Princeps. Livilla later became involved in the plot when it was discovered that she had been Sejanus's lover., with the support of the Julii, either assume the principality themselves or act as regents for the young Tiberius Twin and Caligula. Those who stood in his way were accused of treason.

However, Sejanus's cruel actions finally brought him down: the lawsuits that had been brought against senators and knights after Tiberius's retreat earned him a number of enemies who were unwilling to allow him to assume the Principality. In 31 Sejanus was summoned to the Senate where a letter signed by Tiberius accusing him of treason and condemning him to immediate execution was read to him, Sejanus was put on trial and he and several of his colleagues were executed that same week. On his death he was replaced as Prefect of the Praetorium by Nevio Sutorio Macron.

After the death of Sejanus, a series of trials began in Rome that seemed to have no end. Despite the apathy and indecision that had characterized the beginning of his rule, at the end of it Tiberius decided to rule without qualms. He decimated the ranks of the Senate. All those who had collaborated with or had been associated with Sejanus were tried and executed and their property was confiscated. Tacitus describes it thus:

Executions have become a stimulus for his fury, and he has sentenced all prisoners accused of collaborating with Sejano to death. There are, separated or in piles, countless deaths of all sexes and ages. Relatives and friends were not allowed to be near them, cry their death or even look at them. Espías set rounds to score the mourners who dared to approach. When the corpses were defiled, they were dragged into the Tiber, whose waters they were dumped. The force of terror and cruelty extinguished the penalty.

Rumors began to emerge about the ignominious acts that Tiberius carried out in his place of retirement. Suetonius describes situations of total sexual perversion, where sadomasochism, voyeurism and pedophilia were present. Although it is likely that it was only an invention of his enemies in Rome, these rumors give us an idea of the opinion that the Roman people had of his Princeps during the 23-year reign.

Ending

The assassination of Sejanus and the treason trials damaged Tiberius' image and reputation. After the fall of Sejanus, the withdrawal of Tiberius was complete; the Empire continued to function thanks to the bureaucratic inertia established by Augustus, instead of being directed by the princeps. Tiberius became completely paranoid and spent more and more time in isolation after the death of his son. While Tiberius was in retreat, according to Suetonius the Parthians began a brief invasion while the Dacian tribes and the Germanic tribes of the Rhine made raids into Roman territory.

Tiberius made no arrangements to ensure a peaceful succession. After the death of many of the Julii, his supporters and his own son, the only serious candidates to succeed him were his grandson Tiberius Twin and Germanicus's son Caligula. Despite everything, Tiberius continued without making any type of succession arrangement and only one attempt at the end of his life to name Caligula honorary quaestor is known.

Tiberius died at Misenum on 16 March 37 at the age of 77. According to Tacitus the emperor's death was greeted with enthusiasm among the Roman people, only to suddenly fall silent when news of his recovery was received and rejoice again when Caligula and Macron assassinated him. However, Tacitus's writings are probably apocryphal, as they are not confirmed by any other ancient historians. Tacitus' account may indicate the prevailing sentiment in the senate toward Tiberius at the time of his death. In Tiberius's will, the late emperor delegated joint reign to Caligula and Tiberius Twin. The first thing Caligula did was assume Tiberius' powers and assassinate Tiberius Twin.

Tiberius' downfall was not due to his abuse of power, but his refusal to use it. His reign, apathetic compared to his predecessor's, earned him the animosity of the people. The Senate had been functioning under the leadership of Augustus for years, and when Tiberius wanted to return his autonomy to him, he did not know how to act alone. After failing, Tiberius seemed uninterested in his position. Tiberius is an example of relinquishing power.

Semblance of Caesar

According to contemporary descriptions, Tiberius was of great stature, athletic build, fair complexion, and prematurely bald. Only he had hair left on the nape of his neck, which he let grow, following the fashion of the patricians of the time. He was left-handed, he had eyes of different colors, green and blue, like cats, and although he was myopic, at night he had exceptionally sharp vision. His health was excellent, and there is only evidence that he fell ill twice.

A shy and reserved man, the shame of his baldness had a profound depressive effect on him, to the point of condemning Lucius Cesiano for having made fun of his bald spot in public. He also suffered terrible facial ulcers that made his face ugly and ugly. they forced him to have his face covered with poultices; this dermopathy caused Tiberius to avoid appearing in public.

Resentful of the world, he had a cynical, bitter character and an extremely cruel humor. Suetonius narrates an anecdote according to which Tiberius, frightened by a fisherman from Capri who had scaled a cliff to offer him his best catch, made him rub his face with his fish. In the midst of the torture, the fisherman (who must have been in a similar mood to Tiberius) congratulated himself for not having given him a huge lobster that he had caught. Tiberius sent for it and had them rub his face with it as well.

Legacy

Historiography

Tiberius, on his death in 37, might have been remembered as an example of how to reign. Despite the general hostility with which he is remembered by contemporary and later historians, Tiberius left in the Treasury some three billion sesterces. Rather than embark on costly campaigns abroad, Tiberius decided to strengthen the Empire by building defenses, using diplomacy, and maintaining a policy of passivity in disputes between foreign monarchs. Tiberius was a stronger and more consolidated Empire. Of the authors whose texts on the emperor have survived, only four describe the reign in full detail: Tacitus, Suetonius, Cassius Dio, and Veleyus Paterculus, as well as small fragments written by Pliny the Elder, Strabo, and Marco Anneo Seneca. Tiberius himself wrote an autobiography that Tacitus describes as "short and succinct"; however, this work has been lost.

Publius Cornelius Tacitus

The most detailed report on the reign of Tiberius has come down to us from Publius Cornelius Tacitus and his Annals, whose first six books deal with the subject. Tacitus was a knight — he belonged to the ordo equester — who was born during the reign of Nero in 56. His work is based for the most part on the acta senatus (the act of session of the Senate) and the acta diurna populi Romani (collection of accounts and reports of government and court actions), in the autobiography of Tiberius and in contemporary historians such as Cluvio Rufus, Fabio Rústico and Pliny the Elder whose writings have been lost. Tacitus's description of the emperor is generally negative, gradually becoming harsher as his condition worsens, and the historian mentions a clear degradation of the emperor's psychological state after the death of his son in 23. The historian Tacitus broadly describes the reign of the Julio-Claudian dynasty as unfair and cruel, and the good deeds that happened early in his reign are blamed on sheer hypocrisy. Tacitus also draws on the imbalance of power between the emperors and the Senate and reveals the corruption and tyranny derived from the rulers, dedicating an important part of his story to the trials and persecutions that arose as a result of the restoration of the law of maiestas . The last statement of his sixth book is the best example of his opinion of the emperor:

Their character experiences constant changes. While during the reign of Augustus he was a private citizen who held high positions, he reached his reputation a high level. But after the death of Druso and Germánico his character plunged into evil and misfortune. Finally he tried to get rid of the fear and shame that his own inclinations had stimulated.

Tranquil Suetonian

Suetonius was a knight of the ordo equester who worked in an administrative position during the reigns of Trajan and Hadrian. His great work, entitled The Lives of the Twelve Caesars is a biography of Caesar and the first eleven emperors of Rome from the birth of Julius Caesar to the death of Domitian in 96. Like Tacitus, Suetonius had access to the imperial archives, as well as to the writings of ancient historians such as Aufidio Baso, Cluvio Rufo, Fabio Rústico, and the same letters from Emperor Caesar Augustus. Suetonius's work is, however, more sensationalist and anecdotal than that of his contemporary, highlighting the parts that recount the alleged depravities committed by the emperor upon his retirement in Capri, and praising Tiberius' actions at the beginning. of his reign, emphasizing his modesty.

Veleius Paterculus

The historian Veleyo Patérculo constitutes one of the few contemporary sources to Tiberius, who talks about his person and his reign. Paterculus served under Tiberius for eight years in Germania and Pannonia as prefect of cavalry and legate. Paterculus's work covers the period between the fall of Troy and the death of Livia (29), and gives a very favorable opinion of the emperor and his Prefect of the Praetorium, Sejanus. Although it is not known for sure certain if the bias of the work is due to true admiration or fear of reprisals, it is important to know the fact that Paterculus was assassinated in 31 as a friend of Sejanus, which can give us the idea that there was a true friendship between the two.

Gospels

The gospels mention that during the reign of Tiberius, Jesus of Nazareth was executed on the orders of the governor of Judea, Pontius Pilate. In the Bible, the name of Tiberius is mentioned only once (Gospel according to Saint Luke), in a part in which they mention the promotion of John the Baptist to public service. Although the name of Caesar is mentioned on numerous occasions, no explicit reference is made to Tiberius.

Archaeology

Tiberius's palace in Rome was located on Palatine Hill and its ruins can be visited today. During the reign of Tiberius, no major works were carried out, except for the construction of a temple dedicated to Augustus and the restoration of the Theater of Pompey, which was not completed until the reign of Emperor Caligula.

The remains of the villa of Tiberius in Sperlonga have been recovered and preserved, where a grotto has been found from whose interior various statues have been recovered. Tiberius' complex on Capri is estimated to have comprised a total of twelve villas, of which the famous Villa Jovis is the largest.

Tiberius refused to be worshiped as a god, as had been done to Julius Caesar and Caesar Augustus, allowing only the construction of a temple in his honor in Smyrna.

Herod Antipas named the city of Tiberias, located on the western shore of the Sea of Galilee, after Tiberius.

Essays

Gregorio Maranon. Tiberius: Story of a Grudge 1939

Tiberius in fiction

Tiberius has been represented on various occasions in fiction, both in literature and in film and television.

He is the main character in the novel of the same name by Allan Massie and a minor character in the novel I, Claudio, by Robert Graves. The latter has been adapted into the BBC television series with the same name, being played by George Baker.

Tiberius also appears in the films Ben-Hur; played by George Relph, Caligula; played by Peter O'Toole and The Robe; played by Ernest Thesiger.

James Mason played Tiberius in the miniseries A.D. Anno Domini.

In popular culture

In Spanish, there is the colloquial expression “armar un Tiberio” or “montarse un buen Tiberio”, to mean that there was a great scandal or an unbridled uproar was formed, thereby meaning the worst excesses. This set phrase seems to have its origin in the disorderly and violent lifestyle that characterized the emperor in his last years.

Titles and positions

| Roman Emperor | ||

|---|---|---|

| Predecessor Augusto | in the period 14-37 | Successor Caligula |

| First consulate | ||

| Predecessors Marco Licinio Craso Frugi Cneo Cornelio Léntulo Augur | with Publio Quintilio Varo 13 a. C. | Successors Marco Valerio Mesala Apiano Publio Sulpicio Quirinio |

| Second Consulate | ||

| Predecessors Cayo Marcio Censorino Cayo Asinio Galo | with Cneo Calpurnio Pisón 7 a. C. | Successors Tenth Lelio Balbo Cayo Antistio Veto |

| Third Consulate | ||

| Predecessors Lucio Pomponio Flaco Cayo Celio Rufo | with Germanic Julius Caesar 18 | Successors Marco Junio Silano Torcuato Lucio Norbano Balbo |

| Consulate room | ||

| Predecessors Marco Valerio Mesala Barbado Mesalino Marco Aurelio Cota Maximum Mesalino | with Druso Julio César 21 | Successors Tenth Agrippa Haster Cayo Sulpicio Galba |

| Fifth Consulate | ||

| Predecessors Link Lucio Casio Longino | with Lucio Elio Sejano 31 | Successors Cneo Domicio Enobarbo Lucio Arruncio Camilo Escriboniano |

Contenido relacionado

French Revolution

Hermeric

Ildefonso Cerdá