Threshing

Threshing is the activity and its result, which is done with the cereals, after harvesting, to remove the grain from the chaff.

Depending on the times and regions, various systems have been used to separate the grain from the chaff: We can distinguish two methods, the pestle and the threshing.

The Pestle

Maja used when the amount of harvest is low and when it is important to keep the straw reeds in the best possible condition for later use in roofing, baskets, tying sheaves, etc. and that it was used with cereals with longer straw such as rye.

Striking (crushing) the sheaves of cereal against a clumsy stone, or a board called a clumsy peg. The sheaves held with both hands a bunch caught by the stems, and the spike shook against the surface of majar; thus, it shelled and released the seed. It was used for small quantities and had the advantage that subsequent cleaning was easier. Although the procedure was not as effective as the other systems, as it left some grains in the granzas.

Maja with flail: the flail is a simple tool made up of a long, thin wooden handle tied to a shorter and narrower wooden mallet with which the heap is struck until the seed is separated from the stem. Known, probably, since the Neolithic, it is the most common instrument in Western Europe and throughout the Old Continent. According to studies by the Swedish ethnologist Dag Trotzig, the Iberian Peninsula is the area where the flail is least widespread. It is used above all in the northern areas (from Galicia to the Catalan Pyrenees) and in the mountains; It also occurs in various regions of Portugal. The flail, together with the majar stick, was an instrument typical of modest farmers or day laborers, since the more affluent used the threshing floor.

Threshing

Threshing itself, while shelling the ears, also crushes the straw that can have other uses.

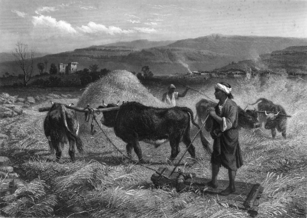

Trampling the harvest scattered on the threshing floor by herds of oxen or horses ("threshing on a loose mare"). This type of threshing was used in Ancient Egypt and Ancient Rome, this would also be the technique described by Xenophon in his book on Economics (Dialogue between Socrates and Iscómaco); in the Spanish Plateau this system was used for small crops of chickpeas and barley (since these shell more easily than wheat and, sometimes, more instruments are not necessary): In the parts where there are mares, they thresh with two, or three rods, than each rod ∫with twelve mares, and in this way∫in one day, when the weather is good, they will thresh fifty, up to∫a hundred loads of wheat. Another example: "Wheat is not threshed by threshing machines, but rather it is broken by horses that are herded in a wheel in number from one hundred to two hundred in the place where the ears lie. This saves a lot of time and work».

The threshing by a mare on the loose is an ancient peasant tradition that takes place in Chile. Mares and horses are used to trample the sheaves to separate the chaff from the grain. Currently there are machines that have displaced this activity. However, it is carried out by tradition, generally in the summer months. The subsequent celebration includes other customary acts, such as Mass and Chilean-style wedding, greyhound dog race, rodeos, typical foods, etc. In Argentina, this threshing method prevailed until the last quarter of the 19th century. It was called "mares leg threshing".

Threshing with threshing: The threshing consisted of a wooden plank, the lower surface of which was embedded with a large number of sharp little stones, usually flakes of flint, and the curved front up like a sled. The trails were drawn by horses or oxen over the pile spread out in a threshing floor, and led by a "trillique", who was generally a rapaz, still too small to do the mowing, hardest work.

After threshing, the cleaning was done by means of winnowing, which consisted of throwing into the air the mixture of straw and grain obtained; the slightest breeze was capable of dragging the balago to one side, while the grain fell in the same place. It is conceivable and very likely that this is the form of winnowing described by Xenophon, vaguely because he assumes it to be well known, in his book Economics.

By the 1930s, all these tasks were manual in Spain. With agricultural mechanization, from the 40s, mechanical threshers began to spread, although threshing continued to be traditional. The winnowing, on the other hand, was done by another machine, the winnowing machine or “wine winnower”. Modern combine harvesters do all the work, from harvesting to separating the grain and straw, which they leave on the ground in sacks and bales, respectively, for collection. Other times, the machine itself stores the grain and, periodically, it is transferred to a warehouse equipped with a hopper pulled by a tractor.

With these changes, a field that used to require 70 people working for 15 or 20 days is now harvested in a day or two, with one machine and two people.

Contenido relacionado

Green revolution

Linum usitatissimum

Zootechnics

Ecological agriculture

Zea