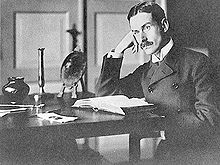

Thomas mann

Thomas Mann (Lübeck, June 6, 1875 - Zurich, August 12, 1955) was a German writer, one of the most important of his generation. He is remembered for the deep critical analysis he developed around the European and German soul in the first half of the XX century, for which which took as main references the Bible and the ideas of Goethe, Freud, Nietzsche and Schopenhauer.

His essays and ideas on political, social, and cultural issues received wide attention. Although he was initially skeptical of Western democracy, he became a staunch supporter of the Weimar Republic in the early 1920s. During the National Socialist period he emigrated to Switzerland and in 1938 to the United States, where he acquired Swiss citizenship. country in 1944. From 1952 until his death, he resided in Switzerland.

Although his best-known work is the novel The Magic Mountain, Thomas Mann received the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1929 “mainly for his great novel, The Buddenbrooks, which has earned increasingly firm recognition as one of the classic works of contemporary literature."

Biography

Childhood and youth (1875-1894)

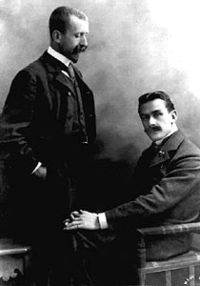

Paul Thomas Mann was born on June 6, 1875 into a wealthy family in Lübeck, then a federal state of the newly created German Empire. Thomas Johann Heinrich Mann, his father, was the owner of a grain trading company who would become a state senator and had married Julia Da Silva-Bruhns, born in Brazil and of Catholic upbringing, who came from a family of German-Brazilian merchants. The couple had five children: the eldest, born in 1871, was the also famous novelist Heinrich Mann and, after Thomas, three others, Julia (1877-1927), Carla (1881-1910) and Viktor (1890-1949).

Mann was baptized on June 11 at St. Mary's Church, a Lutheran church he helped rebuild after World War II. As was the norm in the upper classes, he did not attend primary school but received a private education. In 1882, he entered a high school in which he had to complete six courses, although he was not a good student and had to repeat a year. Then he went in 1889 to the Katharineum, a prestigious baccalaureate institute in which, destined as he was for commerce, he did not receive the classical education in the humanities but the Realgymnasium, a teaching in modern languages more adapted to the practical use.

A poor academic performer, few of Mann's cultural references come from his school days, perhaps with the exception of his knowledge of Latin. In particular, his literary and artistic learning was essentially self-taught, following in these years in the footsteps of Heinrich, his older brother. Schiller, Heine, Nietzsche, Hermann Bahr, and Paul Bourget were the first independent readings of it. He too was fascinated, though not due to Heinrich's influence, by Wagner's music, a fondness he would later attribute to many of his characters.

From his years at the Katharineum come the first known information about the love life of the young Mann. For these more personal aspects of his biography, the available information comes mainly from his memoirs (Story of my life, 1930), from his diaries (although in 1896 he burned those corresponding to his adolescence, he left many references in years later) and the large amount of correspondence that survives, both his own and that of others, for this period, especially that between his brother Heinrich and their mutual friends. In addition, and this is very characteristic of his conception of literature, there are a large number of autobiographical allusions, often unequivocal, scattered throughout his work.

Probably in the winter of 1889, he was attracted to his partner Armin Martens, whom he immortalized as Hans Hansen in his 1903 novel Tonio Kröger. Many years later, in 1955, in a letter addressed to another Katharineum student, she defined Armin as "her first love" and revealed that when she confessed her feelings to him, "she did not know what to do" with them. The following year, He met Williram Timple, in whose house he would stay for a while before he left for Munich and with whom he would never come clean as he did with Armin. Willri appears in The Magic Mountain “sublimated” as Pribislav Hippe, a classmate of Hans Castorp; The common thread of this character is the loan of a pencil, a loan that is accompanied by connotations of love: in 1953, while walking through Lübeck, Thomas Mann still remembered William Timple and his pencil, which had really existed. Williram, Armin and Thomas At that time, they attended some dance classes and, if we are to believe the fiction, in them a girl, Magdalena Brehmer (Magdalena Vermehren in Tonio Kröger), fell in love with Thomas, without there being any indication that that would lead to any kind of relationship between the two.

In his youth, Mann wrote for serious purposes, but in these years he considered himself not a storyteller but a "lyrical-dramatic poet." He composed poetry in the style of Heine, Schiller or Theodor Storm, as well as some plays that Mann would later allude to in a derogatory way and that he ended up destroying, which is why few of his youthful texts survive. In 1893, together with his friend Otto Grautoff, he edited a magazine called Der Frühlingssturm (Spring Storm) of which an issue containing an essay on Heine, some poetry and a story entitled "Vision." Mann later claimed that these early attempts at the narrative genre were inspired by the group of Viennese Symbolists led by Hermann Bahr.

At the age of fifty-one, on October 13, 1891, his father died after leaving the liquidation of the company in his will and, a few months later, his mother moved with her three young children to Munich As soon as he was able to dispose of it, his father's inheritance provided him with a monthly income of between 160 and 180 marks, an amount that at the time alone allowed him to live comfortably, until the war and the subsequent hyperinflation of 1923 made him lose all its value.

Munich (1894-1913)

After completing his studies at the Katharineum, without having obtained a bachelor's degree, he met his family in Munich at the end of March 1894, at first at his mother's house and later at successive addresses of his own, always in the bohemian neighborhood of Schwabing. In October of that same year, he managed to publish a short novel, The Fall, in the magazine Die Gesellschaft. He also went as an auditor for two semesters at the Technical University of Munich where he received classes in economics, mythology, aesthetics, history and literature, until, in July 1895 and in the company of his brother Heinrich, he made his first trip to Italy, where he stayed until October visiting Palestrina and Rome. In August he also began his collaboration for the nationalist and conservative magazine Das Zwanzigste Jahrhundert, in which he published eight articles for a little over a year, almost all reviews. After seeing several publications rejected, the magazine finally Simplicissimus accepted The Will to Be Happy, a story written in December 1895, followed a year later by Little Monsieur Friedemann, the work that gave him allowed him to really start making a name for himself as a writer.

Between October 1896 and April 1898, he traveled again through Italy in the company of Heinrich. On this occasion they visited Venice and Naples to return again to Palestrina and Rome, where in October 1897, in Heinrich's apartment at Via Torre Argentina 34, he began writing his first great work, the novel The Buddenbrooks. Upon returning from Italy, Mann began working, until January 1900, at the magazine Simplicissimus and did a brief military service while continuing to polish the manuscript of The Budenbrooks, which he delivered for publication at the end of 1900, although it was not printed until October 1901. His readings of Schopenhauer correspond to these years, an author whom he surely reached through Nietzsche, and who had a great influence both in this his first great novel as in the rest of his work. Some other works of his from the end of the century (poems, dramas, short novels and essays) have not been preserved because he later considered them of little value and destroyed them.

Between 1900 and 1903 he maintained an intense friendship with homoerotic connotations with the painter and violinist Paul Ehrenberg. Mann reflected his relationship with Ehrenberg in many of his books, especially in Doctor Faustus, a work that he wrote in the 1940s, but whose preliminary notes date from 1901; in it the character of Rudi Schwerdtfeger is Ehrenberg's alter ego. Through his letters and diaries there is also news of a young woman from Munich whom he met in the months before his first trip to Italy, and of Mary Smith, an English tourist whom he met during his month in Florence in 1901. In both cases Mann's description suggests in serious courtship for matrimonial purposes.

In late 1903 or early 1904, he met Katia Pringsheim, the daughter of a prominent family of intellectuals and artists of Jewish origin whose father, Alfred Pringsheim, was a famous mathematician, studies she herself took somewhat exceptionally at the time. They were engaged on October 4, 1904, and the wedding took place on February 11, 1905; ceremony that could not be held by the church since Katia's father was opposed to a Protestant wedding and she herself did not profess any religion. The Manns had six children: Erika (1905-1969), Klaus (1906-1949), Golo (1909-1994), Monika (1910-1992), Elisabeth (1918-2002) and Michael (1919-1977), all of whom would become more or less important in their own right. Mann used as literary material in the novel Your Royal Highness his courtship and wedding with Katia (Imma Spoelmann) and he even reproduced some of the letters they exchanged, but due to his new family relationships these autobiographical allusions began to cause him problems, in a at which time he also had to delay the publication of Sangre de Welsungos when some of its passages were interpreted as anti-Semitic.

On July 30, 1910, Mann's sister, Carla, committed suicide in the family home in Polling (Weilheim) where their mother had moved in 1906. Carla, a not-so-successful actress, was about to get married when she was the victim of blackmail from a former lover and ended her life when she could not find support from her future husband. Thomas's reaction, who reproached Carla for not having sought refuge in the family, was one of the causes of the beginning of her estrangement with her brother Heinrich from her.

During the years before the First World War, Mann's fame and prestige did not stop growing along with his social position: in 1908 he built a large summer house in Bad Tölz and a family mansion in Munich at the who moved in January 1914. But at the same time they were also years of literary insecurity in which he began many projects that he never finished, some of which were definitely abandoned, such as a work on Frederick the Great and the social novel Maya. Perhaps the only great work of this period is Death in Venice, in which the famous writer Gustav von Aschenbach is none other than Thomas Mann himself: he even attributes the authorship of his unfinished works and the paternity of some characters in The Buddenbrooks. The episode stems from a visit Mann made to Venice in 1911, when he also stayed at the Grand Hôtel des Bains on the Lido and had the opportunity to admire a young Pole, identified in 1965 as Baron Wladyslav Moes, Tadzio in the novel.

World War I (1914-1918)

At the outbreak of World War I, Mann took a decidedly nationalist stance and joined the belligerent enthusiasm of the majority to the point that in 1917 he invested in German war bonds, which would later become worthless, the proceeds from the sale of his house in Bad Tölz. He also supported the war effort with several essays, among them Reflections during the war (1914), Letters from the frontline (1914), Frederico and the great coalition (1915) and above all Considerations of an apolitical man (1915-1918).

The Considerations were initially intended as a simple article, but in 1915 Heinrich Mann published his work Zola, where he resolutely opposed German militarism and frontally attacked the theses of his brother, which caused him to expand his essay to the dimensions of a great book. These differences caused the total break between the two and they were only reconciled when in 1922 Heinrich contracted a disease that seriously endangered his life.

The Weimar Republic (1919-1932)

Although Mann, as an intellectual, was always involved in all kinds of public affairs, the evolution of his political ideas never followed very coherent lines. Initially inclined, by temperament and also under Katia's influence, to moderate nationalist parties representing a liberal bourgeoisie in the style of Gustav Stresemann's DVP, he oscillated between citing authors such as Oswald Spengler or even Houston Stewart Chamberlain and Dietrich with some approval. Eckart, and to maintain an ambivalent stance towards both the Russian Revolution and the Bavarian Soviet Republic, whose brief existence he experienced personally. In any case, the end of the war and its outcome led him to become a leading defender of the Weimar Republic: not only did he express his respect for social democratic leaders such as Philipp Scheidemann and especially Friedrich Ebert, whom he knew and frequented, but he did not hesitate to sign manifestos of support or even accept positions, such as member of the Council Film Censor, and later of the Prussian Academy of Arts, whose literature section he helped found. Particularly important, and in stark contrast to many intellectuals of initially conservative and nationalist leanings like his own, was his early frontal opposition to Nazism. In 1921, when the movement was still in formation, he already described it as "nonsense with a swastika" and, later, despite the fact that he himself used in his writings the racial stereotypes widespread at the time, he defined the radical anti-Semitism of the movement as an infamy. that the Nazis flagged in their rise to power.

The end of the war allowed him to continue his interrupted literary projects, and so in 1919 he resumed writing The Magic Mountain, which he had begun in 1913 and published in 1924 with enormous immediate success. In the 1920s his fame was already worldwide (providing him with significant additional income in dollars during the hyperinflation of 1922-1923) and he continued to receive honors and awards, culminating in 1929 with the award of the Nobel Prize for Literature..

In the more free atmosphere of the Weimar years, Mann spoke out more publicly on issues related to homosexuality, going so far as to sign a petition to the Reichstag to have his criminalization revoked. He reflected his position above all in reviews and comments on works by authors such as Paul Verlaine, Walt Whitman, André Gide or August von Platen, although always without making his personal preferences clear, something on which he always prevented any transcendence. public discussion. In August 1927, in Kempen (island of Sylt), he met Klaus Heuser, a young man to whom he felt attracted and who became part of his "gallery", although years later Heuser claimed that Mann had misunderstood the show of kindness from him. In any case, he reviewed the notes on the episode to incorporate the material into Joseph and his brothers, a tetralogy that he began writing in 1926.

Also in the summer of 1927, Julia, Mann's remaining sister and to whom he was very close, committed suicide. He had married a banker in 1900, but the marriage was a failure, he had morphine addiction problems and finally ended up hanging himself.

When from 1929 and the Great Depression the Nazi movement began to seriously aspire to power, Mann did not stop exposing his frontal opposition in public. On February 17, 1930, he delivered his "German Speech" in Berlin, at a ceremony attended by Arnolt Bronnen, Ernst Jünger and his brother Friedrich to provoke debate, while Goebbels gave orders to attend some twenty dressed members of the SA with instructions to provide support in the foreseeable riot. In 1932, despite considering him an outdated figure, he did not hesitate to support Hindenburg's candidacy for the presidency against Hitler.

Exile in Switzerland and the United States (1933-1938)

On February 11, 1933, a few days after Hitler's appointment as chancellor on January 30, Mann began a tour of Amsterdam, Brussels, and Paris giving his lecture "Richard Wagner's Passion and Greatness," which continued with a holiday in Switzerland. Although he did not initially perceive too much danger, the news of the excesses that were beginning to be committed in Germany made him delay his return and, after a brief stay in the south of France, where after a few weeks in Bandol he spent the summer in Sanary-sur- Mer, settled in Küsnacht, on the shores of Lake Zurich, his residence until 1938.

The harassment gradually increased: on April 16, 1933, a group of cultural figures (among them Richard Strauss, Hans Pfitzner, Hans Knappertsbusch, Siegmund von Hausegger and Olaf Gulbransson) signed the manifesto «Protest of the city of Munich, home of Richard Wagner". His cars were confiscated (for SA use) and also on August 15 the house in Munich (in 1937 it was put at the disposal of the Lebensborn organization and ended up destroyed by the allied bombing). Although Mann tried to appeal, it seems that Reinhard Heydrich himself took a special interest in his case until he officially withdrew his German citizenship in December 1936, although shortly before, on November 19, Mann had already obtained a Czechoslovakian passport.

Despite everything, and the insistence of Katia, as well as Klaus, Erika and Golo; Mann long resisted making an explicit denunciation of the new Nazi regime. He had hopes of getting some of his property back and also did not want his work to be banned in Germany. His publisher, the famous Samuel Fischer, also put pressure on him because it would be seriously harmed, although in the end, being also a "Jewish" company from the Nazi point of view, it was forced to transfer the edition of the unauthorized authors to Vienna, as Stefan Zweig and Thomas Mann himself, who ended up publishing an unqualified condemnation in the Neue Zürcher Zeitung on February 3, 1936. Thus, the first two volumes of Joseph and his brothers, The Jacob Stories and Young Joseph, could still be published in Germany in 1933 and 1934; while the third, Joseph in Egypt, appeared in Vienna in 1936 and the last, Joseph the Provider, had to wait until 1943. At the same time, his work also ended up being removal of libraries and bookstores from Fascist Italy in 1938.

On November 19, 1936, Mann became a Czechoslovakian citizen and, during 1937 and 1938, made frequent lecturing trips, including three to the United States, where he moved in September 1938 after obtaining an academic position at the University of Princeton. At this time he focused his literary activity, in addition to the last part of the tetralogy of Joseph, on the novel Charlotte in Weimar, while he continued his political activism: he edited the anti-fascist magazine Mass und Wert (Measure and value ) and wrote essays in opposition to Nazism such as "This peace", against the Munich agreements, and against Adolf Hitler himself. In the latter ("Brother Hitler") is where the famous phrase appears, "Where I am is Germany", which summarizes his commitment and attitude towards exile.

World War II (1939-1945)

On September 1, 1939, Mann celebrated the outbreak of World War II in Saltsjöbaden (Sweden) with Bertolt Brecht and Helene Weigel. They all wanted war to avoid another Munich-like agreement that would leave Poland in the hands of Hitler. However, escaping the Nazis proved difficult for Golo, who had volunteered to fight in France and was taken prisoner after his death. rapid collapse, and for Heinrich who was also in the south of the country. They finally escaped, via Spain and Lisbon, arriving in New York on October 13, 1940.

In the United States he was a great celebrity to the point that Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt received him on January 13 and 14, 1941 at the White House. In the spring he moved from Princeton to Pacific Palisades (California) while he was not he was hesitant to use his fame to disseminate his political views on the war and its consequences, which in this era take on an increasingly leftist tinge. Of particular importance are his radio addresses on the program German Listeners! from the BBC where, from as early as January 1942, he did not stop denouncing the process of extermination of the Jews.

Both Golo and Klaus enlisted in the US Army. Golo entered the secret service and was among the first to enter Germany, while Klaus participated in the conquest of Italy and, as a correspondent for Stars and Stripes, was posted to Germany as early as May 1945 where he was able to verify the degree of destruction that the war had led to. Lübeck was one of the first cities devastated by the allies when, on March 28, 1942, the RAF dropped a mixture of high-powered and explosive bombs on the city. bombings that turned the old town into ruins, but unlike his sons, Mann was unaffected by the results of the bombings. In a BBC program he recalled the bombing of Coventry and always considered that having allowed himself to be dragged by Hitler should bring Germany a just punishment.

In May 1943, he began writing Doctor Faustus, a work in which Theodor W. Adorno served as an advisor for the musical aspects. On June 23, 1944, Thomas Mann and Katia acquired the U.S. citizenship. That same year he actively supported Roosevelt in the campaign for the presidential elections in which he won his last term. Meanwhile he continued to travel and give lectures, such as "Destiny and Mission" (1943), in which he adopted positions closer to Marxism. than at any other time and, later, "Germany and the Germans" (1945) and "The Camps" (1945), about the crimes committed in the concentration camps that were being liberated at the same time.

Postwar (1946-1951)

After the war, Mann was reluctant to return to Germany, despite the fact that he received several public requests, including that of Walter von Molo. He was well informed by his children about the internal situation and Erika also insisted on it, not only because of the chaotic situation but also because of the risk of political manipulation by the allies. Molo requested his presence and help as an intellectual, but there were also serious differences between the exiles and opponents of Nazism. Bertolt Brecht had already reproached him in 1943 for his indifference to the Democratic opponents who had remained in Germany and, in a famous polemic, the writer Frank Thiess even went so far as to oppose the comfort of those who had chosen to flee abroad against the who suffered the war from Germany. The controversy was complicated by the fact that many of the representatives of the "internal exile" had maintained varying degrees of collaboration with the Hitler regime.

On May 21, 1949, tormented and addicted to drugs, Mann's eldest son, Klaus, died. On March 11, 1950, his brother Heinrich died. Although when he arrived in the United States Heinrich had obtained a contract as a scriptwriter for Warner Brothers, problems such as the alcoholism of his wife Nelly plunged him into financial problems so serious that Katia and Thomas ended up having to pay him a monthly allowance.

Return to Europe and final years (1952-1955)

In the late 1940s, Mann began to feel uncomfortable in the United States. The McCarthyite persecution had been unleashed and Mann's more left-wing writings as well as his visit to Weimar, in the Soviet-occupied zone, earned him the accusation of "America's fellow traveler Nr.. I") as well as "premature anti-fascism". More uncomfortable was Erika's situation, much more radical than her father, who had been interrogated by the FBI as a suspected Stalin hired agent and "party member." So finally, in July 1952, she decided to settle permanently in Switzerland.

From Switzerland, he visited both parts of Germany several times and received multiple tributes each time, including the Goethe Prize (West Germany) and the Goethe National Prize (East Germany). He was also made honorary president of the Deutsche Schillerstiftung in Weimar (1953) and honorary citizen of his hometown Lübeck (1955).

On July 18, 1955, while he was in the Dutch town of Noordijk, Mann began to feel severe pain in his left leg, for which it was decided that he be transferred by plane to Zurich. Although he was told that it was a simple "phlebitis", the real cause had been a thrombosis that, on the morning of August 12, led to a tear in the abdominal aorta. He died at eight o'clock that same afternoon accompanied by his daughter Erika and his wife Katia.

Work

Based on Mann's own family, the novel The Buddenbrooks (in some of which the author uses Low German, spoken in the north of the country) chronicles the decline of a family of merchants of Lübeck, over three generations.

In this early stage of his work, he focused attention on the conflictive relationship between art and life, which he addressed in Tonio Kröger, Tristán and La death in Venice, and would culminate later with Doctor Faustus. In Death in Venice he describes the experiences of a writer in a Venice ravaged by cholera; Said work supposes the culmination of the aesthetic ideas of the author, who elaborated a peculiar psychology of the artist.

The Magic Mountain (Der Zauberberg, 1924), for its part, tells the story of an engineering student who plans to visit a sick cousin in a Swiss sanatorium in order to keep him company for three weeks, which finally become seven years. During this time, the protagonist, Hans Castorp, will oppose medicine and his particular point of view on human physiology, he will fall in love and establish a relationship with a multitude of interesting characters, each one with his particular way of being and political ideology. Through all of this, Mann reviews contemporary European civilization. The novel, which he began to write in 1913, shows his ideological evolution during those years: after the war was over, he resumed writing, rewriting all the previous material and incorporating the impact produced on him by the war experience that Germany had gone through.

Mann was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1929 mainly in recognition of the immense popularity he achieved after the publication of The Buddenbrooks (1901) and The Magic Mountain, as well as as well as for his numerous short stories, although only the first of these works was expressly cited at the award ceremony.

Later novels: Charlotte in Weimar (1939), in which Mann returns to the world portrayed by Goethe in The Misadventures of Young Werther (1774). In Doctor Faustus (1947), the author takes as reference the old German legend of Faust, as well as its different versions (Christopher Marlowe, Goethe), as well as various elements from the lives and work of Nietzsche, Beethoven and Arnold Schoenberg. The novel tells the story of the composer Adrian Leverkühn, who makes a pact with the devil to achieve artistic glory. Through the tragic figure of his protagonist, Mann traces a refined design of the corruption of German culture of his time, which would end up leading to the horrors of World War II.

The seminal work is the tetralogy Joseph and his brothers (1933–1942), an imaginative version of the Biblical story of Joseph, told in chapters 37 to 50 of the Book of Genesis. The first volume tells of the establishment of the family of Jacob, the father of Joseph. The second relates the life of young Joseph, who has not yet received the great dowries that await him, and his enmity with his ten brothers, who end up betraying him and selling him as a slave to Egypt. In the third volume, José becomes Potifar's butler, but ends up imprisoned when he rejects the advances of his benefactor's wife. The last book shows the mature Joseph in the position of administrator of the granaries of Egypt. Hunger draws José's brothers to this country, and José cleverly stages a scene to make himself known to them. In the end, the reconciliation brings the whole family back together.

Another outstanding novel is Confessions of the swindler Felix Krull (1954), which was left unfinished after the writer's death, although begun when he was a young writer, it recovered the irony about the nature of the human being that it had characterized many of his earlier works.

Mann's personal diaries, made public in 1975, reveal his internal struggle against an always latent homosexuality, which found reflection in his books, most notably in his well-known work Death in Venice (Der Tod in Venedig, 1912), in which the aging protagonist falls in love with a fourteen-year-old boy named Tadzio. Gilbert Adair's book The Real Tadzio describes how, in the summer of 1911, Mann stayed at the Grand Hôtel des Bains in Venice with his wife and brother, feeling attracted to a child eleven-year-old Pole, named Władysław Moes. Considered a classic of homosexual literature, Death in Venice has been the subject of a Visconti film and a Britten opera.

Alfred Kerr, a German critic who was a critic of the writer, sarcastically referred to the novel, since it "made pedophilia something excusable if it was practiced by the cultivated middle classes". Mann had a close relationship with the young man in his youth. violinist and painter Paul Ehrenberg whose significance is unknown. However, the writer chose to get married and have a family. His works also present other sexual themes, such as incest, in the work The Chosen One .

In Death in Venice, on the other hand, we witness the symbolic encounter between beauty and resistance to the natural decline of age, decadence, both personified in the figure of Gustav von Aschenbach, character who acts at the same time as a metaphor for the ideal of purity of the Nazi regime (recalling Nietzsche's criticism of traditional asceticism, denial of life). Mann equally valued contributions from other cultures; he adapted, for example, an old Indian fable to one of his works, The changed heads .

Nietzsche's influence on Mann is easily detectable throughout his work, especially in relation to Nietzsche's ideas on decadence and the relationship between disease and creativity. The first two would help to remedy the ossification that the traditional civilization of the West had reached. In this way, the "overcoming" that Mann alludes to in the introduction to The Magic Mountain and the opening to a new world of possibilities that open up before its protagonist, the young Hans Castorp, occur in a context, indeed, of disease, as is a mountain sanatorium.

His work is the record of a vitalist consciousness open to multiple possibilities, that is, it exposes very well the tensions inherent to the more or less fruitful contemplation of said possibilities. He himself summed it up as follows, on the occasion of the awarding of the Nobel Prize: «The value and significance of my work must be left to the judgment of history; for me they have no other meaning than a life led consciously, that is to say, conscientiously».

Taken as a whole, Mann's career is a remarkable example of the "repeated postbertad" that Goethe thought characteristic of the man of genius. Both in style and in thought, he experienced much more daringly than is commonly assumed. With The Buddenbrook We attend one of the latest novels in the old style, a patient and detailed design of the fortunes and misfortunes of a family.(Henry Hatfield, Thomas Mann1962)

Novel

- 1901 The Buddenbrook (Buddenbrooks – Verfall einer Familie)

- 1909 Royal Highness (Königliche Hocheit)

- 1924 The Magic Mountain (Der Zauberberg)

- 1933-1943 Joseph and his brothers (Joseph und seine Brüder)

- 1933 History of Jacob (Die Geschichten Jaakobs)

- 1934 The young Joseph (Der junge Joseph)

- 1936 Joseph in Egypt (Joseph in Ägypten)

- 1943 José el Proveedor (Joseph, der Ernährer)

- 1939 Carlota in Weimar (Lotte in Weimar)

- 1947 Doktor Faustus (Doktor Faustus)

- 1951 The chosen one (Der Erwählte)

- 1953 The black swan (Die Betrogene: Erzählung)

- 1954 Confessions of the scammer Felix Krull (Bekenntnisse des Hochstaplers Felix Krull. Der Memoiren erster TeilUnfinished

Short narrative

- 1893 Vision (Vision)

- 1894 The Fall (Gefallen)

- 1896 The will to be happy (Der Wille zum Glück)

- 1897 Death (Der Tod)

- 1897 Little Mr. Friedemann (Der kleine Herr Friedemann)

- 1897 The clown (Der Bajazzo)

- 1898 Deception

- 1898 Tobias Mindernickel (Tobias Mindernickel)

- 1899 The closet (Der Kleiderschrank)

- 1899 Revenge

- 1900 Luisita (Luischen)

- 1900 The road to the cemetery (Der Weg zum Friedhof)

- 1902 Gladius Dei

- 1902 Tristan (Tristan)

- 1903 Tonio Kröger

- 1903 The hungry. A study

- 1903 The child prodigy (Das Wunderkind)

- 1904 An instant of happiness (Ein Glück)

- 1904 In the house of the prophet (Beim Propheten)

- 1905 Difficult time (Schwere Stunde)

- 1905 Welsungos Blood (Wälsungenblut)

- 1908 Anecdote (Anekdote)

- 1909 Ferroviary accident (Das Eisenbahnglück)

- 1911 How Jappe and Do Escobar got into a fight (Wie Jappe und Do Escobar sich prügelten)

- 1912 Death in Venice (Der Tod in Venedig)

- 1918 Lord and dog (Herr und Hund; Gesang vom Kindchen: Zwei Idyllen)

- 1923 Tristan and Isolda (Tristan und Isolde)

- 1925 Disorder and early penalties (Unordnung und frühes Leid)

- 1930 Mario and the magician (Mario und der Zauberer)

- 1940 Trocada heads (Die vertauschten Köpfe – Eine indische Legende)

- 1943 The law (Das Gesetz)

- 1953 The fool (Die Betrogene)

Essay

- Bilse und ich (1906)

- Im Spiegel (1907)

- Friedrich und die große Koalition (1915) [3]

- Considerations of an apolytic (Betrachtungen eines Unpolitischen (1918) [4]), translation into Spanish by León Mames.

- Goethe und Tolstoi (1923) [5]

- Von deutscher Republik (1923) [6]

- Lübeck als geistige Lebensform (1926) [7]

- Theodor Fontane (1928) [8]

- Deutsche Ansprache. Ein Appell an die Vernunft. (1930) [9]

- Goethe als Repräsentant des bürgerlichen Zeitalters (1932) [10]. In Cervantes, Goethe, Freud

- Goethe und Tolstoi. Zum Problem der Humanität. (1932) [11]

- Goethes Laufbahn als Schriftsteller (1933) [12]

- Leiden und Größe Richard Wagners (1933)

- Freud und die Zukunft (1936) [13]. In Schopenhauer, Nietzsche, Freud.

- Vom zukünftigen Sieg der Demokratie (1938) [14]

- Schopenhauer (1938) [15]. In Schopenhauer, Nietzsche, Freud.

- Achtung, Europe! (1938) [16]

- Dieser Friede (1938) [17]

- Das Problem der Freiheit (1939)

- Dieser Krieg (1940)

- Hear, Germans: radio speeches against Hitler (Deutsche Hörer (1942) [18])

- Deutschland und die Deutschen (1945) [19]

- Nietzsches Philosophie im Lichte unserer Erfahrung (1947) [20]. In Schopenhauer, Nietzsche, Freud

- Neue Studien (1948)

- Goethe und die Demokratie (1949) [21]

- Ansprache im Goethejahr 1949 [22]

- Meine Zeit (1950) [23]

- Michelangelo in seinen Dichtungen (1950) [24]

- Der Künstler und die Gesellschaft (1953) [25]

- Gerhart Hauptmann (1952) [26]

- Versuch über Schiller (1955)

- Richard Wagner and music (Wagner und unsere Zeit), collected by Erika Mann.

Memories

- 1930 Relation of my life (Lebensabriß)

Daily

- Journals 1918 -1955 (Tagebücher)

Theater

- 1906 Fiorenza

- 1954 Luthers Hochzeit (fragment)

Family tree of the Dohm-Mann family

| Heinrich Mann | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Julia Mann | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thomas Johann Heinrich Mann | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ludwig Herman Bruhns | Carla Mann | Gustaf Gründgens | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Júlia da Silva Bruhns | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Maria da Silva | Viktor Mann | Erika Mann | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hans Ernst Dohm | Thomas Mann | W. H. Auden | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hedwig Dohm | Katharina Pringsheim | Klaus Mann | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ernst Dohm | Alfred Pringsheim | Klaus Pringsheim, sir. | Golo Mann | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ida Marie Elisabeth Dohm | Monika Mann | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Gustav Adolph Schleh | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hedwig Dohm | Marie Pauline Adelheid Dohm | Elisabeth Mann | Angelica Borgese | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Wilhelmine Jülich | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Eva Dohm | Giuseppe Antonio Borgese | Dominica Borgese | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Michael T. Mann | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Contenido relacionado

Charles Durning

Troilus and Cressida

Christ