Thomas Hobbes

Thomas Hobbes (/hɒbz/; Westport, near Malmesbury, April 5, 1588-Derbyshire, December 4, 1679), in certain ancient texts Thomas Hobbes of Malmesbury, was an English philosopher considered one of the founders of modern political philosophy. His best-known work is Leviathan (1651), where he laid the foundations of contractarian theory, of great influence on the development of Western political philosophy. In addition to the philosophical field, he worked in other fields of knowledge such as history, ethics, theology, geometry or physics.

In addition to being considered the quintessential theoretician of political absolutism, in his thought there are concepts that were fundamental to liberalism, such as the right of the individual, the natural equality of people, the conventional character of the State (which will lead to the subsequent distinction between this and civil society), the representative and popular legitimacy of political power (since it can be revoked if it does not guarantee the protection of its subordinates), etc. His conception of the human being as equally dependent on the laws of matter and the movement (materialism) continues to enjoy great influence, as well as the notion of human cooperation based on self-interest.

Biography

Hobbes was a controversial character in his time, although his thought has been very influential afterwards; maybe he was too modern for his time and too conservative for the ones that followed; In fact, in 1666 his books were burned in England for having been considered an atheist and after his death they were publicly burned again. While he was alive, he had to fight relentlessly against two great enemies: the Church of England and the University of Oxford.

His thought was formed in close contact with the European circles of René Descartes, Pierre Gassendi and Galileo Galilei, not only from England, through the intellectual cenacle brought together by the Cavendish family, of which he was tutor on several occasions, but also directly through his long journeys through France, Italy and Germany. The civil wars between puritan parliamentarians and royalists made him take refuge in Paris in 1640 and, he returned to his country eleven years later, his defense of a strong and conservative monarchical power earned him a pension from King Charles II of England.

Youth and education

Thomas Hobbes was born in Westport, now part of Malmesbury, Wiltshire, on April 5, 1588. He was a premature baby; His birth would have been caused when his mother heard about an imminent invasion by the Spanish Great Armada, also called Invincible. That is why Hobbes later affirmed, explaining his own origin: "My mother gave birth to twins: myself and fear."

There is little information about his childhood; even the name of his mother is unknown. His father Thomas was vicar of Charlton and Westport, but when he was involved in a fight with the local clergy he was forced, to avoid greater evils, to leave London without his family, consisting of his wife and three children, who remained in the care of the philosopher's paternal uncle, Francis Hobbes, several years older, since he had sufficient means as he was a rich merchant without a family.

So from the age of four he was educated at Westport and then at Malmesbury, from where he went on to the private school of Robert Latimer, an Oxford graduate. Given the intellectual precocity that the boy showed (at the age of six he learned Latin and Greek, and from eight to fourteen he worked on putting Euripides' Medea into Latin verse), around 1603, with only fifteen years old, he went to Magdalen Hall College in Oxford, the forerunner of Hertford College, directed by the Puritan John Wilkinson.

At Oxford University Hobbes felt little attraction to scholastic learning, and preferred to do readings according to his criteria and outside the program; for this reason he spent a brief period in the navy and did not complete his Bachelor of Arts degree until 1608; However, his talent did not go unnoticed and he was recommended as tutor to the son of William Cavendish, Baron Hardwick and later Earl of Devonshire, also called William, by his teacher at Magdalen, Sir James Hussey. With this he began his life long relationship with this family.

Hobbes befriended his pupil William, and the two went on a grand tour of France, Italy, and Germany together in 1608 and 1610. On the Continent, Hobbes assimilated European scientific and critical methods and from then on scorned the scholasticism that had reluctantly learned at Oxford, although at that time his main interest was the study and analysis of the Greco-Latin classics and especially his great translation of Thucydides' History of the Peloponnesian War; this edition appeared the year of the death of his student and friend (1628) and was the first direct translation from Greek into English, a difficult job even for an expert. Three of the speeches included in Horae subsecivae, observations and speeches (1620) are also believed to be from this period.

Although he associated with literary figures such as playwright Ben Jonson and worked briefly as clerk for empiricist philosopher and chancellor Francis Bacon, an introducer of the essay genre to England, he did not extend his efforts to philosophy until after 1629. His patron Cavendish, then Earl of Devonshire, he had died a victim of the plague in June 1628 and found himself out of a job when dismissed by the Dowager Countess.

However, his good references as a tutor ensured that he continued in the same trade and he took as a pupil Gervase Clifton, son of the honorable baronet of the same name. For this he had to travel to Paris, but he was again hired by the Cavendish family in 1631 as tutor to William Cavendish, eldest son of his previous student. And it was then, during the next seven years, that he definitely awakened his interest in philosophy. He visited Florence in 1636 and then participated in the disputes of the disbelieving Pyrrhonian libertines in Paris, maintained by the mathematician and philosopher Marin Mersenne. This opened the doors of the Parisian salons and encouraged him to publish his discoveries in psychology and physics. Hobbes describes in an autobiography to what extent his philosophical vocation burned in him, his state of incessant meditation, "by boat, by car, on horseback"; It is at this moment in his life that he conceives that the principle of his physics will be the conatus or movement, the only reality that generates natural things. Because it seemed to him that this principle was capable of founding even human sciences such as psychology, morality and politics.

In Paris

Hobbes's first interest was in studying the physics of motion, yet he disdained experimental work. He then began to conceive of a mechanistic and materialistic philosophical system to which he would dedicate his entire life. He first separately elaborated an ordered doctrine on bodies, which showed how physical phenomena were universally explainable in terms of motion. He then extracted man from the realm of nature and, in a separate treatise, showed what specific bodily movements were involved in the production of the particular phenomena of sensation, knowledge, affections, and passions by which man, moved chiefly by fear, and desire enters into a relationship with other equal men in a war of all against all. Finally, he considered how men were moved to enter from that hostile natural state into an artificial society, granting the monopoly of violence to a higher authority, and argued how this had to be regulated with a social contract if men did not want to return to it. fall into "brutality and misery." He therefore proposed to unite the separate phenomena of the Body, Man and the State.

Hobbes returned to England in 1637, when the country was in turmoil with disagreement between parliamentarians and the king. However, around 1642 he had already written a short treatise called Elements of natural and political law that was not published and only circulated in manuscript among his acquaintances. However, a pirated version was published ten years later. Although much of the Elements of Natural and Political Law seems to have been composed before the session of the Short Parliament, there are polemical parts of this work which clearly show his position in the growing political crisis. Despite everything, the vast majority of the elements of Hobbes's political thought hardly changed between his Elements of Natural and Political Law and his Leviathan, which shows that the events of the English Civil War had little effect on his contractual doctrine.

However, Leviathan's arguments were modified when dealing with the need for consent to create political obligations. Namely, Hobbes wrote in The Elements of Law that patrimonial kingdoms were not necessarily formed by the consent of the governed, while in Leviathan he argued that they were. This perhaps reflected Hobbes's view of the settlement controversy or his reaction to treatises published by Sir Robert Filmer and others between 1640 and 1651.

When in November 1640 the Long Parliament succeeded the Short, Hobbes felt that he was endangered by the circulation of his treatise and fled to Paris, not returning for eleven years. In Paris, he rejoined the Mersenne Cenacle and wrote a critique of René Descartes's Meditations which was printed as the third among the attached Objections, obtaining Response of Descartes in 1641. A different set of observations on Descartes's other works were disseminated only after the conclusion of their mutual correspondence.

Hobbes also expanded his own works with a third section, De cive, which was completed in November 1641. Although initially only in private circulation, it was well received and included arguments repeated for a decade more. late in his Leviathan. He then revisited the first two sections of his work and published only a short treatise on optics (Tractatus opticus) included in the collection of scientific treatises published by Mersenne as Cogitata physico-mathematica in 1644. He had established a good reputation in philosophical circles and in 1645 he was chosen along with Descartes, Gilles de Roberval and others to adjudicate the controversy between John Pell and Longomontanus on the problem of squaring the circle.

English Civil War

When the English Civil War finally broke out in 1642, and the royalist cause was on the verge of defeat in mid-1644, supporters of King Charles began to go into exile in Europe. Many went to Paris and Hobbes was thus able to treat them. This revitalized Hobbes's political hopes and his De Cive was republished and distributed to a wider sphere. Samuel de Sorvière's Amsterdam Elzevirian press published in 1646 this work with a new "Preface" and some new notes to answer the objections.

In 1647, Hobbes took the post of mathematical instructor to the young Charles, Prince of Wales, who had arrived from Jersey in July. He held this post until Charles went to Holland in 1648.

Surrounded by exiled royalists Hobbes composed his Leviathan, where he expounded his theory of civil government in relation to the political crisis caused by the war. Hobbes compared the State to the Biblical monster Leviathan, composed of men and created under the pressure of human needs, but dissolved by civil war aroused by human passions. The work closed with a general "Review and Conclusion," in response to the war, which answered the question: Does a subject have the right to change allegiance when a former sovereign's power to protect him is irrevocably lost?

During the years of the composition of Leviathan, Hobbes remained in or near Paris. In 1647, however, a serious illness nearly finished him off and left him incapacitated for half a year. On recovery he resumed his labors and completed the work about 1650. Meanwhile he was translating that of De Cive ; scholars disagree on whether Hobbes himself translated it.

In 1650, a pirated edition of The Elements of Law natural and Politic was published. It was divided into two small volumes. In 1651, the Latin into English translation of De Cive was published under the title Philosophical Rudiments concerning government and society. In the meantime, the larger work went to print, and finally appeared in the middle of 1651, entitled Leviathan, or the Matter, Form, and Power of a Common, Ecclesiastical, and Civil Wealth. It had the famous engraving on the title page depicting a giant crowned above the waist rising above hills overlooking a landscape, holding sword and staff and made up of tiny human figures.

The work had an immediate impact. Soon Hobbes was more praised and blamed than any other thinker of his time. The first effect of his publication was to break his link with the exiled royalists, who might well have killed him. The secularist spirit of his book greatly angered both Anglicans and French Catholics. Hobbes appealed to the revolutionary English government for his protection and fled to London in the winter of 1651. After his submission to the Council of State, he was allowed to immerse himself in private life in Fetter Lane.

Maturity in England

In 1658, Hobbes published the final section of his philosophical system, completing the outline he had planned more than 20 years earlier. De Homine consisted for the most part of an elaborate theory of vision. The rest of the treatise dealt briefly with some of the most frequently discussed topics in Human Nature and Leviathan. In addition to publishing some controversial texts in mathematics and physics, Hobbes also continued to produce philosophical works. From the time of the Restoration, he acquired a new prominence. "Hobbism" became synonymous with everything that a respectable society should denounce. The young king, Hobbes's former student, now Charles II, remembered Hobbes and summoned him to court to grant him a hefty pension of £100.

The king was important in protecting Hobbes when, in 1666, the House of Commons introduced a bill against atheism and desecration. That same year, on October 17, 1666, it was ordered that the committee to which the bill was referred "should be empowered to receive information touching such books as atheism, blasphemy, and desecration... in particular [...] Mr. Hobbes's book called Leviathan". Hobbes was terrified at the prospect of being labeled a heretic, and proceeded to burn some of his compromising documents. At the same time, he examined the actual state of the law of heresy. The results of his research were first announced in three Short Dialogues added as an Appendix to his Latin translation of Leviathan, published in Amsterdam in 1668. In this appendix, Hobbes intended to show that since the Tribunal of the Commission had been put down, there was no court of heresy at all to which he could appeal, and that nothing could be heresy except to oppose the Nicene Creed, which, he held, the Leviathan i> did not.

The only consequence of the bill was that Hobbes would never again be able to publish anything in England on subjects relating to human conduct. The 1668 edition of his works was printed in Amsterdam because he was unable to obtain a license from the censor for publication in England. Other writings were not made public until after his death, including Behemoth: the History of the Causes of the Civil Wars of England and of the Tips and Artifices by which they were carried out from the year 1640 to the year 1662.

For some time, Hobbes couldn't even respond, no matter what his enemies tried. Despite this, his reputation abroad was formidable, and noble or learned foreigners who came to England never failed to pay their respects to the old philosopher.

His final works were an autobiography in Latin verse in 1672, and a translation of four books of the Odyssey into English rhymes, which led to a complete translation of the Iliad in 1673 and the Odyssey in 1675.

Death

In October 1679, Hobbes suffered from a bladder disorder and then a fit of paralysis, from which he died on December 4, 1679, aged 91. It is said that his last words were: "A great leap in the dark", uttered in his final moments of consciousness.His body was buried in the church of Saint John the Baptist in Ault Hucknall (Derbyshire).

Philosophical-social situation of his time

- In the dawns of the Renaissance, the Italian philosopher Nicholas Machiavelli explained in his main work, The Prince (1513), the theory that the ruler should not rule his acts by moral norms or from natural law, but must recognize as the only guide the good of the State.

- For his part, Jean Bodin argued that the State should assume absolute sovereignty (summa potestas) about the town.

- Contrary to the concept of State-based reason argued by the above were formulated the contractual theories of Althusius, according to which sovereignty rests in the people, and the iusnaturalism of Hugo Grocio, which defined injustice as what seems contrary to the community of sensitive beings.

- Samuel von Pufendorf, who applied to law the method of deductive mathematics sciences, acquired value the concept of reciprocal respect.

- In his most famous treatise, Leviathan (1651), Hobbes formally pointed out the passage of the doctrine of natural law to the theory of law as a social contract. According to this English philosopher, in the condition of a state of nature all men are free and yet live in the perpetual danger of a war of all against all (Bellum omnium contra omnes). From the moment the submission of a people ' s covenant to the rule of a sovereign opens a possibility of peace, not the truth, but the principle of authority (as long as it is the guarantor of peace) constitutes the basis of the law.

Philosophical thought

Thomas Hobbes has been considered throughout the history of thought as a dark person. In fact, in 1666, his books were burned in England after being accused of being an atheist. Later, after his death, his works are publicly burned again. During his lifetime, Hobbes had two great enemies with whom he maintained strong tensions: the Church of England and the University of Oxford. Hobbes's work, however, is considered one of the fundamentals in the break with the line of the Middle Ages and the beginning of Modernity. His descriptions of the reality of the time are brutal. He would later say regarding his birth: "Fear and I were born twins." The phrase alludes to the fact that his mother gave birth prematurely due to the terror instilled by the Spanish Invincible Armada, which was approaching the British shores.

Mechanistic Thinking

Though best known for his political philosophy, Thomas Hobbes wrote on a wide range of fields including history, geometry, theology, ethics, general philosophy, and political science.

Many of his opinions are controversial, such as his defense of physicalism or mechanistic materialism, a theory according to which the nature of everything that exists in the world is exclusively physical and that it leaves no room for the existence of other natural entities, such as the mind, soul, nor supernatural. According to Hobbes, all animals, including humans, are nothing more than flesh and blood machines.

By the mid-17th century, the time Hobbes was writing, this metaphysical theory was more widely accepted. Knowledge of the physical sciences increased rapidly and provided increasingly clear explanations of phenomena that were previously confused or misinterpreted.

Hobbes was always in contact with the Royal Society of London, a scientific entity founded in 1660 and had met French thinkers such as Marin Mersenne, Pierre Gassendi, Descartes and the Italian astronomer Galileo Galilei, who is considered the father of science modern, and was closely linked to Francis Bacon whose thinking had contributed to revolutionizing scientific practice. In the field of science and mathematics, Hobbes saw the perfect counterpart to the medieval scholastic philosophy that he had tried to reconcile the apparent contradictions between science and faith. Like many thinkers of the time, he believed that science had no limits and that thanks to it any natural phenomenon in the world could receive a scientifically formulated explanation.

Man is a machine

In Leviathan, Hobbes affirms that the universe, that is, all the mass of things, is corporeal (it has a material body). He defends the idea that each of the bodies has length, hardness and depth, and that what does not have a body is not part of the universe.

Although Hobbes affirms that the nature of everything is purely physical, he does not say that man can perceive everything physical. He declares that some bodies and objects, which they call spirits, are imperceptible even though they occupy space and have physical dimensions. Some of them are animal spirits and are responsible for most animal activity, especially human activity. These animal spirits move around the body and transmit information.

Hobbes defended the concept that human beings are purely physical and therefore governed by the laws of the universe. In these two concepts, his thinking is similar to Spinoza's. However, he differs to a great extent from this by stating that the human being is more than a biological machine. Hobbes interpreted the mental nature by presenting a general and rather schematic view of what he thought science would end up revealing. Even so, he only manages to cover certain mental activities such as appetite, vision and voluntary motor skills, all phenomena that can be explained from a mechanistic point of view. According to Hobbes, the person continually moves to achieve his desires.This movement is classified into two types: approach, when the person approaches the things he desires; and of distance, when it moves away from things that endanger his life. Thus, he says that society is always on the move.

For apart from the sensations and thoughts, the mind of man knows no other movement, although with the help of language and method, the same powers can be elevated to such height that distinguish man from all other living creatures.LeviathanChapter III: Consequences or series of imaginations

In the introduction to Leviathan, using the Delphic injunction "Know thyself!" as a starting point, Hobbes presents a peculiar reading thereafter. Addressed explicitly in the chapter De Corpore, where Hobbes states that we can know the human mind not only by synthetic methods, but also "by the experience of any man who will only examine his own mind", that is, through introspection we can know the behavior of the human being.

Compatibilism

Hobbes was also the modern inventor of compatibilism, the idea that necessary causes and voluntary actions are compatible. Hobbes already thought that every act of the will and every desire comes from a cause, following a causal chain back to God. But a person acts freely if he does not find an obstacle in doing what he has the will to do. That is, we are free if we are able to do what we want without impediment.

What is freedom. LIBERTAD means, properly speaking, the absence of opposition (by opposition I mean external impediments to the movement); it can apply to both irrational and inanimate creatures and rational ones. [...] According to this genuine and common significance of the word, it is a LIBRE MAN who in those things that he is able by his strength and by his wit is not hindered to do what he wants.LeviathanChapter XXI: From the "freedom" of the subjects

Philosophy of religion

Hobbes tries to apply to God and other religious entities, such as angels, the concept of animal spirit. However, he defends that only God, in no other physical spirit, can be determined as incorporeal. According to Hobbes, the divine nature of God's attributes is not something that the human intellect can fully comprehend, so the term "incorporeal" it is the only one capable of recognizing and honoring the unknowable substance of God.

Many people have called Hobbes an atheist, both during his lifetime and more recently. However, the word "atheist" it didn't mean the same thing in the 17th century. However, he makes it clear that he believes that the existence and nature of all religious entities is a matter of faith, not science, and that God, in particular, will always remain beyond our comprehension. All that the human being can know of God is that he exists and that he is the first cause and operator of the universe.

Political Thought

The time of Hobbes is characterized by a great political division that confronted two well-defined factions:

- Monarchs, who defended the absolute monarchy, claiming that the legitimacy of this came directly from God.

- Parliamentarians, who claimed that sovereignty must be shared between the king and the people.

Hobbes maintained a neutral position between both sides, since, although he affirmed the sovereignty of the king, he also affirmed that his power did not come from God, although he declined more in favor of the monarchy.

Leviathan

Along with John Locke's Two Treatises on Civil Government and Rousseau's The Social Contract, Leviathan is a one of the first important works that address human nature, the origin of society and how society is organized.

In Leviathan, Hobbes expounded his doctrine of the founding of legitimate states and governments and created an objective science of morality. This gave rise to the theory of the social contract. Leviathan was written during the English Civil War; Much of the book is concerned with demonstrating the need for a strong central authority to prevent the evil of discord and civil war.

Starting from the definition of man and his characteristics, he explains the appearance of law and the different types of government that are necessary for coexistence in society. The origin of the State is the pact that people make among themselves, through which they are subordinated from that moment to a ruler, who in turn seeks the good of all subjects and himself. In this way, the social organization is formed.

From a mechanistic understanding of human beings and their passions, Hobbes posits what life would be like without government, a condition he calls the state of nature. In that state, each person would be entitled, or licensed, to everything in the world. This, Hobbes argues, would lead to a "war of all against all" (bellum omnium contra omnes). The description contains what has been called one of the best-known passages in English philosophy, describing the natural state humanity would be in, were it not for the political community:

In such a condition, there is no place for the industry; for its fruit is uncertain; and consequently there is no culture on the earth; there is no navigation, nor use of the goods that can be imported by sea; no comfortable building; there are no instruments to move and remove things that require much force; no knowledge of the face of the earth; no account of time; without arts; no letters; no society; and that is the worst of all, continual fear and danger.LeviathanChapter XIII: Of the natural condition of humanity as regards its happiness and misery

In such a state, people fear death and lack both the things necessary for a comfortable life and the hope of being able to work for them. So, to avoid this, people agree to a social contract and establish a civil society. He talks about the right of nature, which he refers to as the freedom to use the power that each one has to guarantee self-preservation. When a person realizes that he cannot continue living in a state of continuous civil war, the law of nature arises, which limits man to not carry out any act that threatens his life or that of others. From this is derived the second law of nature, in which each man renounces or transfers his right, through a pact or agreement, to an absolute power that guarantees a state of peace.

According to Hobbes, society is a population under a sovereign authority, to whom all individuals in that society cede some rights for the sake of protection. Any power exercised by this authority cannot be resisted, because the protector's sovereign power derives from individuals surrendering their own sovereign power for their protection. Individuals are therefore the authors of all decisions made by the sovereign. "He who complains about the damage of his sovereign complains that he himself is the author, and therefore he should not accuse anyone other than himself." himself, nor to himself from injury because hurting oneself is impossible». There is no doctrine of separation of powers in Hobbes's discussion. According to Hobbes, the sovereign must control civil, military, judicial, and ecclesiastical powers, even words.

Ideas Regarding Crime

Although he is not generally classified as such, Hobbes can be recognized as one of the ancestors of the Classical School of criminology, since he himself already recognized in Leviathan the principles of legality, jurisdictional and proportionality of the sentence.

Insofar as it also recognizes the existence of a calculation of costs and benefits of the actors, since if the penalty is less than the benefits of the crime, it ceases to be a punishment and becomes the price of illegality, thus it maintains that “if the damage inflicted is less than the benefit of satisfaction that naturally follows the crime committed, this damage is not included in that definition, and is rather the price or redemption and not the penalty assigned to a crime. Indeed, it is consubstantial to the penalty to have as its end the disposition of men to obey the law, an end that (if it is less than the benefit of the transgression) is not achieved; rather, one moves away in the opposite direction."

Some authors also link Hobbes to the economic theories of criminology as well as to the Classical School since they maintain that the deterrence of punishment depends on its being effective and there being no impunity, in Hobbes's words: «Ambition and greed are also absorbing and oppressive passions, and, on the other hand, reason does not always act to resist them; therefore, as soon as the hope of impunity appears, its effects are manifested".

Religious Views

Hobbes's religious views remain controversial, as many positions have been attributed to him, ranging from atheism to orthodox Christianity. In Elements of Law, Hobbes provided a cosmological argument for the existence of God, saying that God is "the first cause of all causes".

Hobbes was accused of atheism by several contemporaries; Bramhall accused him of teachings that could lead to atheism. This was a major accusation, and Hobbes himself wrote, in his reply to Bramhall's The Catching of Leviathan, that "atheism, impiety and the like are words of the greatest possible slander' 34;. Hobbes always defended himself against such accusations. Also in more recent times, scholars such as Richard Tuck and J. G. A. Pocock have been very vocal about his religious views, but there is still widespread disagreement about the exact meaning of the points of view. Hobbes' unusual views on religion.

As Martinich has pointed out, in Hobbes's time the term "atheist" it was often applied to people who believed in God but not in divine providence, or to people who believed in God but also held other beliefs that were considered incompatible with that belief or judged incompatible with orthodox Christianity. He says that this "type of discrepancy has led to many errors in determining who was an atheist in the early modern period". In this extended early modern sense of atheism, Hobbes took positions that were in complete disagreement with the teachings of the church of his time. For example, he repeatedly argued that there are no incorporeal substances and that all things, including human thoughts, and even God, heaven, and hell are corporeal, moving matter. He argued that "though the Scriptures acknowledge spirits, yet nowhere does it say that they are incorporeal, which means that they have neither dimensions nor quantity". (In this view, Hobbes claimed to be following Tertullian). Like John Locke, he also asserted that true revelation can never be at odds with human reason and experience, although he also argued that people should accept revelation and its interpretations for the reason that they should accept the orders of their sovereign, to avoid war.

While in Venice, Hobbes met Fulgenzio Micanzio, a close associate of Paolo Sarpi, who had written against the papacy's claims to temporal power in response to Pope Paul V's Interdict against Venice, which refused to recognize papal prerogatives. James I had invited both men to England in 1612. Micanzio and Sarpi had argued that God wanted human nature and that human nature indicated the autonomy of the state in temporal affairs. When he returned to England in 1615, William Cavendish corresponded with Micanzio and Sarpi, and Hobbes translated the latter's letters from Italian, which circulated among the duke's circle.

Works

- 1602. Latin translation Medea of Eurípides (loss).

- 1620. Three speeches in Horae Subsecivae: Observation and discourses (A Discourse of Tacitus, A Discourse of Romeand A Discourse of Laws).

- 1626. De Mirabilis Pecci, Being the Wonders of the Peak in Darby-shire(poem first published in 1636)

- 1629. Eight Books of the Peloponnesian Warre, translated with an introduction of Tucídides: History of the Peloponnesian War

- 1630. A Short Tract on First PrinciplesBritish Museum, Harleian MS 6796, ff. 297-308: ed. critique with comments and French translation by Jean Bernhardt: Court traité des premieres principes, Paris, PUF, 1988 (doubtful authority) Some critics attribute this work to Robert Payne.

- 1637. A Briefe of the Art of Rhetorique (in the Molesworth edition the title is The Whole Art of Rhetoric)

- 1639. Tractatus opticus II(British Library, Harley MS 6796, ff. 193-266; 1.a full edition 1963)

- 1640. Elements of Law, Natural and Politic (circulated only in small copies, and the 1st printed edition, without Hobbes' permission in 1650)

- 1641. Objections ad Cartesii Meditationes de Prima Philosophia (3rd series of Objections)

- 1642. From Cive (Latin, 1.a limited edition)

- 1643. De Motu, Loco et Tempore (1st edition of 1973 with the title: Thomas White's Examined World)

- 1644. Part of the Praefatio to Mersenni Ballistica (in F. Marini Mersenni minimi Cogitata physico-mathematica. In quibus tam naturae quàm artis effectus admirandi certissimis demonstrationibus explicantur)

- 1644. Opticae, liber septimus (written in 1640) Universae geometriae mixtaeque mathematicae synopsis, edited Marin Mersenne (reprinted by Molesworth in OL V pp. 215-248 with title Tractatus Opticus)

- 1646. A Minute or First Draught of the Optiques (Harley MS 3360; Molesworth published only the dedication to Cavendish and the conclusion at EW VII, pp. 467-471)

- 1646. Of Liberty and Necessity (is published without Hobbes' permission in 1654)

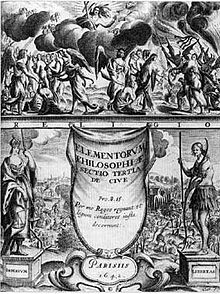

- 1647. Elementorum Philosophiae Sectio Tertia De Cive (2nd expanded edition with a new Preface to the Reader)

- Treaty on the Citizen [Elements of Philosophy, Section III]. Joaquín Rodríguez Feo Edition. Madrid, Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distance (UNED), 2008. ISBN: 9788436255744

- 1650. Answer to Sir William Davenant's Preface before Gondibert

- 1650. Human Nature: or The fundamental Elements of Policie (first thirteen chapters of The Elements of Law, Natural and Politicpublished without the authorization of Hobbes

- 1650. Pirated Edition of The Elements of Law, Natural and Politic, changed to include two parts:

- Human Nature, or the Fundamental Elements of Policie.

- De Corpore Politico.

- 1651. Philosophical Rudiments concerning Government and Society (translated from English) From Cive).

- 1651. Leviathan, or the Matter, Forme, and Power of a Commonwealth, Ecclesiasticall and Civil. Spanish Editions:

- Leviathan (translation by Manuel Sánchez Sarto, 1940), Mexico: FCE, reprinted in 1984 Barcelona: Sarpe, 1984 2 vols.

- Leviathan (translation from Antonio Escohotado, 1979) Madrid: Editora Nacional.

- Leviathan (translation from Antonio Escohotado, 2003). Buenos Aires: Losada. ISBN: 9789500392532.

- Leviathan or the matter, form and power of an ecclesiastical and civil state (translation of Carlos Mellizo, 2009). Madrid: Alianza Editorial. ISBN: 9788420682808.

- 1654. Of Libertie and Necessitie, Treatise.

- 1655. De Corpore (Latin).

- 1656. Elements of Philosophy, The First Section, Concerning Body (English anonymous translation) De Corpore).

- 1656. Six Lessons to the Professor of Mathematics

- 1656. The Questions concerning Liberty, Necessity and Chance (reprinted from Of Libertie and Necessitie, Treatisewith the addition of Bramhall's replica and Hobbes' response to Bramahall)

- 1657. Stigmai, or Marks of the Absurd Geometry, Rural Language, Scottish Church Politics, and Barbarisms of John Wallis.

- 1658. Elementorum Philosophiae Sectio Secunda De Homine.

- Treaty on Man [Elements of Philosophy, Section II]. Joaquín Rodríguez Feo Edition. Madrid, Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distance (UNED), 2008. ISBN: 9788436255133

- 1660. Examinatio et emendatio mathematicae hodiernae qualis explicatur in libris Johannis Wallisii.

- 1661. Dialogus physicus, sive De natura aeris.

- 1662. Physics Problem (translated to English in 1682 as Seven Philosophical Problems).

- 1662. Seven Philosophical Problems, and Two Propositions of Geometru (posthumously published).

- 1662. Mr. Hobbes Considered in his Loyalty, Religion, Reputation, and Manners. Through Letter to Dr. Wallis (Autobiography).

- 1666. De Principis " Ratiocinatione Geometrarum.

- 1666. A Dialogue between a Philosopher and a Student of the Common Laws of England (published in 1681).

- 1668. Leviathan (Latin translation)

- 1668. An Answer to a Book published by Dr. Bramhall (is published in 1682)

- 1671. Three Papers Presented to the Royal Society Against Dr. Wallis. Together with Considerations on Dr. Wallis his Answer to them.

- 1671. Rosetum Geometricum, sive Propositiones Aliquot Frustra antehac tentatae. Cum Censura brevi Doctrinae Wallisianae de Motu.

- 1672. Lux Mathematica. Excussa Collisionibus Johannis Wallisii.

- 1673. Translations to English by Homer: The Iliad and Odyssey.

- 1674. Principia et Problemata Aliquot Geometrica Antè Dperota, Nunc breviter Explicata " Demonstrata.

- 1678. Decameron Physiologicum: Or, Tens of Natural Philosophy.

- 1679. Thomae Hobbessii Malmesburiensis Vita. Authore seipso (Latin autobiography, translated into English in 1680).

- Posthumous work

- 1680. An Historical Narration concerning Heresie, And the Punishment thereof (in Spanish): A Historical Narration on Heresy, and Consequent Punishment).

- 1681. Behemoth, or The Long Parliament. Spanish edition: Behemoth (Rodilla translation, M.A.). Madrid: Tecnos.

- 1682. Seven Philosophical Problems (English translation Physics Problem, 1662)

- 1682. A Garden of Geometrical Roses (English translation Rosetum Geometricum, 1671)

- 1682. Some Principles and Problems in Geometry (English translation Principia et Problemata, 1674)

- 1688. History Ecclesiastica Carmine Elegiaco Concinnata.

Contenido relacionado

Attila

Hatshepsut

Zapatista