Theory

A theory (from the Greek theōría) is a logical-deductive (or inductive) system made up of a set of hypotheses, a field of application (of what that the theory deals with, the set of things that it explains) and some rules that allow us to draw consequences from the hypotheses. In general, theories serve to make scientific models that interpret a broad set of observations, based on the axioms or principles, assumptions, postulates, and logical consequences consistent with the theory.

General aspects

It is very difficult to explain in detail what constitutes a theory unless you specify the field of knowledge or field of application to which it refers, the type of objects to which it applies, etc. For this reason it is possible to formulate different definitions of theory depending on the context and the approach applied:

A theory is not knowledge, allows knowledge. A theory is not an arrival, it is the possibility of a departure. A theory is not a solution, it is the possibility of dealing with a problem.

In general, theories by themselves or in the form of a scientific model allow predictions and inferences to be made about the real system to which the theory is applied. Likewise, theories allow economic explanations of experimental data and even make predictions about facts that will be observable under certain conditions. In addition, most theories allow to be expanded from the contrast of their predictions with the experimental data, and can even be modified or corrected, through inductive reasoning.

Science is constituted and, above all, it is built by the expansion of explanatory fields through the succession of theories that, even maintaining their truth value in their explanatory field, are falsified by experiments and replaced or expanded by later theories.

Etymology

The word derives from the Greek θεωρειν,"contemplate" or rather it refers to a speculative thought. Like the word specular, it is related to "look at", "see". It comes from theoros (representative), formed from thea (sight) and horo (see). According to some sources, theorein was often used in the context of watching a theatrical scene, which perhaps explains why the word theory is sometimes > is used to represent something provisional or not completely real.

The term soon acquired an intellectual meaning and was applied to the ability to understand, to "see" beyond the sensory experience, through the understanding of things and experiences, understanding them under a concept expressed in language through words.

This way of valuing intellectual knowledge corresponds to the Greeks, understanding that things happen according to laws, that is, necessarily. Things are and happen that way because they are and have to be that way. Thus, they overcome the vision of cultural traditions or mythical, magical or religious explanations.

Theory and reality

The term "theoretical" or "in theory" It is used to indicate the difference between the data obtained (object of study) from the model with respect to the observable phenomena in the experience or experiment of reality. Frequently, it indicates that a particular result has been predicted by the theory but has not yet been observed. For example, until recently, black holes were considered theoretical objects. Similarly, Percival Lowell conjectured the existence of Pluto in 1906, although it was not observed and identified as a new planet until 1930, by Clyde Tombaugh.

A good theory must be able to make predictions that can be confirmed by new experiments or observations. A theory is therefore a good model of its object of study, that is, it adequately represents the empirical facts of said object of study. A corroborated theory expands the explanatory field and allows updating the knowledge of the facts that we have about the world. The theories act as complex hypotheses about sets of laws established by the previous theories. Experimental observations turn them into scientific theories accepted as epistemologically valid by the scientific community. Nowadays, scientific theories are the product of research programs.

Theory and science in Antiquity and the Middle Ages

Plato is perhaps the first to elaborate a model with the pretense of science in the interpretation of knowledge of reality. The idea of theory in his approach is the character of & # 34; vision of the soul & # 34; that through sensible experience it recalls the true knowledge that consists in the contemplation of the ideas that the soul has had in its life in the other world. This world is an imperfect copy of the true model that is reality. Knowledge of superior ideas is promoted through dialectic, which is true science.

Aristotle, his disciple, defines science as the knowledge that goes from the necessary to the necessary by means of the necessary, also pointing out the logical and formal nature of science.

But for Aristotle, knowledge comes from the intuition of the understanding capable of penetrating the essence of the first substance that is being known in experience. For this reason, scientific knowledge, as knowledge that is not only necessary but universal, is It constitutes in the predicates of the essential and therefore universal concept of substance, taken as the subject of the predication, second substance and accidents whose reality is predicated by the analogy of Being. Reality, then, is known through concepts.

These ways of understanding scientific knowledge as theory remained until the late Middle Ages when the value of concepts was called into question, as well as the idea of a merely logical, syllogistic and qualitative science. Knowledge of the individual and the importance of experience through quantitative measurements in its relationship with the qualities of Aristotelian forms begin to be valued in a different way, beginning the path of a new empirical logic.

Scientific theory

An approach to a hypothetical-deductive system that constitutes a scientific explanation or description of a related set of observations or experiments. Thus, a scientific theory is based on hypotheses or assumptions verified by groups of scientists (sometimes an assumption is not directly verifiable but most of its consequences are). It generally covers several verified scientific laws and sometimes deducible from the theory itself. These laws become part of the basic assumptions and hypotheses of the theory that will encompass the knowledge accepted by the scientific community in the field of research and is accepted by the majority of specialists.

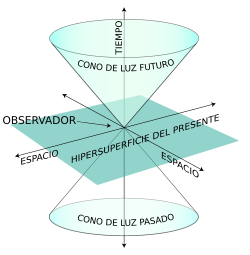

In science, a theory is also called a model for understanding a set of empirical facts. In physics, the term theory generally means a mathematical framework derived from a small set of basic principles capable of producing experimental predictions for a given category of physical systems. An example would be "electromagnetic theory", which is usually taken as a synonym for classical electromagnetism, whose specific results can be derived from Maxwell's equations.

For a given body of theory to come to be considered as part of established knowledge, it is usually necessary for the theory to produce a critical experiment, that is, an experimental result that cannot be predicted by any other already established theory.

According to Stephen Hawking in (A Brief History of Time), "a theory is good if it satisfies two requirements: it must accurately describe a large class of observations on the basis of a model that contains only a few arbitrary elements, and must make concrete predictions about the results of future observations". He then proceeds to state: "Any physical theory is always provisional, in the sense that it is only a hypothesis; can never be proven. No matter how many times the results of experiments agree with some theory, one can never be sure that the next time the result will not contradict it. On the other hand, you can refute a theory by finding only one observation that disagrees with its predictions."

For Mario Bunge (1969), the construction of a scientific theory is always the construction of a more or less refined and consistent system of propositions that unifies, analyzes and deepens ideas.

Social Sciences

Theories exist not only in the natural and exact sciences, but in all fields of academic study, from philosophy to literature to social science. Example in Sociology: The Grand Theory, with T. Parsons' Theory of action systems, in Cultural Anthropology with B. zapata's Culture

Middle-range theories of M. Weber with 'The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism' with an aspect of society. Micro level theory, the current religious pluralism in the United States further delimiting the field and the time.

Characteristics of scientific theories

Often the phrase "Well, it's just a theory", is used to disqualify controversial theories such as the theory of evolution, but this is largely due to a confusion between the words theory and guess.

A conjecture is, at best, an unverified assumption consistent with selected data, and often a belief based on unrepeatable experiments, anecdotes, popular opinion, or "wisdom of the ancients".

Theory, in science, is called a set of descriptions of knowledge that has a firm empirical basis, that is, when:

- It is consistent with pre-existing theory to the extent that it has been experimentally verified, although it will often show that pre-existing theory is false in a strict sense.

- It is supported by many lines of evidence instead of a single foundation, ensuring in this way that probably, if not totally correct, is at least a good approximation.

- He has survived, in the real world, many critical evidence that could have faked it.

- It makes predictions that may someday be used to falseate it.

- It is the best known explanation, in the sense of the Navaja de Occam, of between the infinite variety of alternative explanations for the same data.

This is true of such established theories as the theory of combustion, theory of evolution, special and general relativity, quantum mechanics (with minimal interpretation), plate tectonics, etc.

On the other hand, the use of the term "theory" it is sometimes confusing as is the case with string theory and 'theories of everything', which are probably best characterized at the moment as a bundle of competing hypotheses but do not constitute a proper theory.

Finally, there are conjectures that are called "theories" even if they do not respond to the scientific method. A good example of a "theory" unscientific is Intelligent Design. Likewise, other sets of claims such as homeopathy are not pseudoscience scientific theories either.

Development of scientific theories

In popular parlance, a theory is often seen as little more than an assumption or hypothesis. On the other hand, in science and in general academic use, a theory is much more than that: it is an established scientific paradigm that explains much or all of the available data and offers verifiable valid predictions. In science, a theory can never be proven true because we can never assume that we know everything there is to know about it. Instead, theories stand as long as they are not refuted by new data, at which point they are modified or superseded.

Theories start with empirical observations like 'sometimes water turns to ice'. At some point, the curiosity or need to discover the reason for it arises, which leads to the theoretical/scientific phase. In scientific theories, this then leads to research, in combination with auxiliary and other hypotheses (see scientific method), which can then ultimately lead to a theory. Some scientific theories (such as the theory of gravity) are so widely accepted that they are often taken for laws. This, however, is based on an incorrect assumption about what theories and laws are: they are both not rungs on a ladder of truth, but different sets of data. A physical law is a general statement based on observations.

Some theories that have been proven false are Lamarckism and the theory of the geocentric universe. Sufficient evidence has been accumulated to declare these theories false, as there is no evidence to support them and better explanations have taken their place.

Types of theory

There are two categories of ideas that can lead to theories: if an assumption is not supported by observations it is known as a conjecture, on the other hand, if it is supported, it is a hypothesis. A hypothesis may turn out to be false. When this occurs, the hypothesis must be modified to fit the observation, or it must be discarded.

A theory is different from a theorem. The first is a model of physical events and cannot be proved from basic axioms. The second is a statement of a mathematical fact that follows logically from a set of axioms. One theory is also different from a physical law model of reality while the second is a proposition about what has been observed.

Theories can become accepted if they are capable of making correct predictions (confirmed by observation). Simple and mathematically elegant theories tend to be accepted in preference to those that are more complex. The process of accepting theories, or of extending existing theories, is part of the scientific method.

Object of study

The method used by science to obtain knowledge involves experimentation and/or observation as well as reasoning. For some epistemologists, knowledge as a translation or reconstruction of reality implies the representation/interpretation of observable facts, and warns about the risk of error and illusion that this entails.

The object of study or material reality studied is the set of observable facts that are represented in a theory, although observable facts that could be represented in a theory could be included. a theory that generalizes to the first.

Clarification of the meaning "object of study".

If we consider the first meaning of the word "object" from the Dictionary of the Royal Spanish Academy, we could say that the "object of study" it is all that can be matter of knowledge. By using the word "may" it assigns a virtual or potential connotation to the object, which means that although it may be a matter of knowledge, it is not yet. For this reason the concept "object of study" It can be used as a noun in research projects and protocols, as what is intended to be known. Once the investigation is underway, the "object of study" it becomes a "subject of study", that is to say, an adjective is added to the noun. For example: a certain species of plant can be "object of study" inside a research project, but becomes a "study subject" when it is already exposed or subjected to the investigation process. It is only a matter of properly using the meanings of the words "object" or "subject" according to the Dictionary of the Royal Spanish Academy.

Examples of theories by scientific disciplines

- Biology: Theory of Evolution

- Chemistry: Atomic Theory

- Communication: Critical Theory - Hypodermic Theory - Functional Theory

- Physics: Theory of the Big Bang - Theory of Relativity - Quantum Theory of Fields

- Geography: Theory of central places

- Geology: Continental deriva - Plate tectonics

- Mathematics: Theory of the Caos

Theory in mathematics

In mathematics, a theory is a set of propositions closed under implication and logical deduction, that is; if "P" and "P implies Q" are propositions of a theory then Q must also be a proposition of that theory, since it is deducible from the previous ones.

In mathematical logic, "theory" is the term used for a set of formulas of certain axioms and all proven theorems from these. More exactly if it is considered a mathematical object or a class of mathematical objects , a theory of denoted as is a set of first order formulas (theory language propositions) about that are true. A set of axioms for a theory is a subset of statements such that from them and certain logical rules of deduction can be demonstrated any inconsistencies within the theory. Obviously the same set constitutes a trivial and uninteresting axiomatization . An interesting axiomatization should identify a few basic propositions or axioms that can deduce the complete theory:

- A T theory is said to be recursivamente axiomatizable if there is another theory T' recursiva such that the theorems of T' are the same as those of T.

- A theory T is said finitely axiomatizable if there is a T' theory with a finite amount of axioms such that T's theorems and T's are the same.

Gödel's incompleteness theorem states that no consistent theory, with a finite number of recursively enumerable axioms (in a language at least as powerful as arithmetic), may include all true propositions. However, arithmetic is a complete theory by adding a set of infinite and non recursive axioms. In other words Gödel's theorem only states that if is a type of arithmetic theory:

Or equivalently:

Theoretical models

Humans construct theories in order to explain, predict, and master different phenomena (inanimate things, events, or the behavior of animals). In many circumstances, theory is seen as a model of reality. A theory makes generalizations about observations and consists of a coherent and interrelated set of ideas.

A theory has to be somehow testable; for example, one might theorize that an apple will fall when released, and then drop an apple to see what happens. Many scientists argue that religious beliefs are not verifiable and therefore are not theories but a matter of faith.

Contenido relacionado

Paralogism

Atomism

Democracy