Theodosius I the Great

Theodosius I (in Latin, Theodosius, Cauca or Itálica, January 11, 347 - Milan, January 17, 395), also known as Theodosius the Great, was Roman Emperor from January 19, 379 until his death. During his reign he faced and overcame a war against the Goths and two civil wars, and was instrumental in establishing the Nicene creed as the orthodoxy of Christianity. Theodosius was also the last emperor to rule the entire Roman Empire from 394 until his death, when the administration of the Roman state was permanently divided between two separate courts, one western and one eastern.

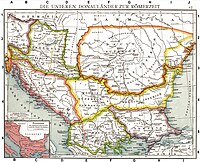

Born in Spain, Theodosius was the son of a high-ranking general, under whose direction he rose through the ranks of the army. In 374, Theodosius already held an independent command in Moesia, where he had some success against the invading Sarmatians. Not long after, he was forced to retire and his father was executed in obscure circumstances, but Theodosius soon regained his position after some intrigues and executions at the court of Emperor Gratian. In 379, after the Eastern Roman Emperor Valens was killed in battle at Adrianople against the Goths, Gratian appointed Theodosius to succeed him and take charge of the army at a dangerous time. The new emperor's insufficient resources and his already depleted armies were not enough to drive out the invaders and, in 382, the Goths were allowed to establish themselves south of the Danube River as autonomous allies of the Empire. In 386, Theodosius signed a treaty with the Sasanian Empire, which divided the long-disputed Kingdom of Armenia and ensured a lasting peace between the two powers.

Theodosius was a strong supporter of the Christian doctrine of consubstantiality and an opponent of Arianism. He called a council of bishops in Constantinople in 381 which confirmed the first as orthodoxy and the second as heresy. Although Theodosius interfered little in the functioning of traditional pagan cults and appointed non-Christians to high positions, he was unable to prevent or punish the damage done to several Hellenistic temples of classical antiquity, such as the Serapeum of Alexandria, destroyed in clashes. between Christians and pagans following the application of anti-pagan Theodosian legislation by Bishop Macellus. During the first years of his reign, Theodosius ruled the eastern provinces, while the west was supervised by the emperors Gratian and Valentinian II, with whose sister Gala married. Theodosius sponsored various measures to beautify his capital and principal residence, Constantinople, most notably the expansion of the Forum Tauri, which became the largest public square known in antiquity. Theodosius undertook two military campaigns to the west twice, in 388 and 394, after Gratian and Valentinian were assassinated, to defeat the two claimants, Magnus Maximus and Eugenius, who rose to replace them. Theodosius' final victory in September 394 made him sole emperor of the empire, but he died a few months later and was succeeded by his two sons, Arcadius in the eastern half of the empire and Honorius in the west. He had been invested as Dominus Noster Flavius Theodosius Augustus upon accession to the imperial dignity and was deified after his death as Divus Theodosius .

Traditional historiography has considered Theodosius a diligent administrator, austere in his habits, merciful, and a devout Christian. In the centuries after his death, Theodosius was considered a staunch defender of Christian orthodoxy that decisively defeated paganism. Modern scholars of his figure, however, regard this as an interpretation of the history of the Christian writers rather than an accurate representation of historical truth. He is also credited with bringing about a revival of classical art that some historians have termed the "Theodosian Renaissance". Although his pacification of the Goths ensured peace for the Empire during his reign, his status as an autonomous people within the Roman borders caused problems for successive emperors. Theodosius has also been criticized for defending his own dynastic interests at the cost of two civil wars.Theodosius' two sons proved weak and incapable rulers, reigning through a period of foreign invasions and court intrigues that severely weakened the Empire. The descendants of Theodosius ruled the Roman world for the next six decades, with the east-west divide lasting until the fall of the Western Roman Empire at the end of the century V.

Origins and military career

Teodosio was born in Hispania, in Cauca (present-day Coca) or in Itálica or its surroundings, the son of a military officer, Teodosio the Elder, known at the time as comes Theodosius. He accompanied his father to Britannia to help put down the Great Conspiracy in 368. He was military commander (doge) of Moesia, a Roman province on the lower Danube, in 374. However, soon after, and about the time of his father's sudden fall from grace and execution, Theodosius withdrew to Spain. The reason for his withdrawal, and the relationship, if any, between him and the death of his father is not clear. It is possible that he was removed from his command by Emperor Valentinian I after the loss of two of Theodosius' legions to the Sarmatians in late 374.

The death of Valentinian I in 375 created political pandemonium. Fearing more persecution due to his family relations, Teodosio withdrew to his Spanish properties, where he adapted to the life of a provincial patrician.

From 364 to 375 the Roman Empire was ruled by two co-emperors, the brothers Valentinian I and Valens; when Valentinian died in 375, his sons, Valentinian II and Gratian, succeeded him as rulers of the Western Roman Empire. In 379, after Valens was killed in the battle of Adrianople, Gratian, to replace the fallen emperor, appointed Theodosius co-august of the East. Gratian in turn was assassinated in a rebellion in 383, after which Theodosius appointed his eldest son, Arcadius, co-august for the East. After the death in 392 of Valentinian II, whom Theodosius had supported against a series of usurpers, Theodosius ruled as sole emperor, naming his youngest son Honorius co-august for the West (in Milan, 23 January 393), and defeating the usurper Eugenius on September 6, 394, in the battle of the Frigid (Vipava river, present-day Slovenia).

Offspring

By his first wife, the probably Hispanic Aelia Flacila Augusta, he had two sons, Arcadio and Honorio, and a daughter, Aelia Pulqueria; Arcadius was his heir in the East and Honorius in the West. Both Aelia Flacilla and Pulcheria died in 385.

His second wife, never declared Augusta, was Galla, daughter of Emperor Valentinian I and his third wife Justina. Theodosius and Galla had three children who were a boy, Gratian, born in 388 who died young, and a daughter, Aelia Galla Placidia (392–450). Placidia was the only descendant to reach adulthood and later became Empress; a third child, a boy named John, died with his mother during childbirth in 394.

Arcadius' (r. 395-408) successor in the East was his son Theodosius II (r. 408-450). Honorius (r. 395-423) had no children, and after his death the Western throne passed to Galla Placidia's son, Valentinian III (r. 425-455). Valentinian married Licinia Eudoxia, daughter of Theodosius II and had two daughters with her, Eudocia, who married the Vandal prince Huneric, and Placidia, who married the future emperor Olybrius (r. 472). The Eastern throne passed to Marcian (r. 450-457) through his marriage to Pulcheria, the sister of Theodosius II. Valentinian III was assassinated in 455 and was briefly succeeded by Petronius Maximus (r. 455), who to legitimize his throne married the widow of Valentinian III and daughter of Theodosius II. With the deaths of Valentinian III (455), Petronius Maximus (455) and Marciano (457) the Theodosian dynasty came to an end, both in the East and in the West.

Diplomatic policy with the Goths

The Goths and their allies, Vandals, Taifali, Bastarnae, and Carpal natives, entrenched in the provinces of Dacia, eastern Lower Pannonia, absorbed Theodosius' attention. The Gothic crisis was so profound that his co-emperor Gratian relinquished control of the Illyrian provinces and withdrew to Trier in Gaul to allow Theodosius to act unhindered. A major weakness in the Roman position after the defeat at Adrianople was the recruitment of barbarians to fight other barbarians. To rebuild the Eastern Roman Army, Theodosius needed to find capable soldiers and so he turned to the most qualified men at hand: the barbarians recently established in the Empire. This caused many difficulties in the battle against the barbarians as the newly recruited fighters had little or no loyalty to Theodosius.

Theodosius was forced into the costly expedient of shipping his recruits to Egypt and replacing them with more experienced Romans, but there were still shifting alliances that produced military setbacks. Gratian sent generals to rid the Illyrian dioceses of Goths (Pannonia and Dalmatia), and Theodosius was finally able to enter Constantinople on November 24, 380, after two campaigns. The final treaties with the rest of the Gothic forces, signed on 3 October 382, allowed large contingents of mainly Thervingian Goths to settle along the southern Danubian border in the province of Thrace and govern themselves quite extensively. The Goths then established within the empire had, as a result of treaties, military obligations to fight for the Romans as a national contingent, rather than being fully integrated into Roman forces. However, many Goths would serve in Roman legions and others as foederati, during individual campaigns; while bands of Goths of shifting allegiances became a destabilizing factor in internecine struggles for control of the Empire. In the last years of Theodosius' reign, one of the emerging leaders named Alaric participated in Theodosius's campaign against Eugenius in 394, only to revert to his rebellious behavior against Theodosius's son and successor in the East, Arcadius, shortly after. the death of Theodosius.

Civil wars in the Empire

After Gratian's death in 383, Theodosius' interest turned to the Western Roman Empire since the usurper Magnus Maximus had taken all the western provinces except Italy. The self-proclaimed threat was hostile to Theodosius's interests, since the reigning Emperor Valentinian II, Maximus's enemy, was his ally. Theodosius, however, was unable to do much with Maximus due to his still inadequate military capacity and was forced to keep his attention on local affairs. However, when Maximus began his invasion of Italy in 387, Theodosius was forced into action. The armies of Theodosius and Maximus met in 388 at Poetovius and Maximus was defeated. On August 28, 388 Maximus was executed.

Trouble arose again, on May 15, 392 Valentinian II was found hanged in his residence in the city of Vienne in Gaul. The magister militum and Valentinian's tutor, Arbogastes attributed it to suicide. Arbogastes and Valentinian had frequently disputed rule over the Western Roman Empire, and Valentinian had also complained of Arbogastes' control over it to Theodosius. So when the news of his death reached Constantinople, Theodosius believed, or at least suspected, that Arbogastes was lying and that he had plotted Valentinian's disappearance. Arbogastes chose Eugenio, formerly a teacher of rhetoric. Eugenio sought, in vain, the recognition of Theodosius. In January 393, Theodosius gave his son Honorius the full rank of Augustus of the West, citing Eugenius's lack of legitimacy.

Theodosius campaigned against Eugene. The two armies met at the Battle of the Frigid in September 394. The battle began on 5 September 394 with Theodosius' full frontal assault on Eugenius's forces. Theodosius was repelled and Eugene thought the battle was over. In Theodosius' camp the loss of the day lowered morale. It is said that Theodosius was visited by two "celestial horsemen dressed all in white" who gave him encouragement. The next day, the battle began again and Theodosius's forces were aided by a natural phenomenon known as the Bora, which produces cyclonic winds. The Bora blew directly into Eugenio's forces and broke the line.

Eugenio's camp was taken by storm and Eugenio was captured and shortly after executed. Thus Theodosius became the sole emperor.

Theodosius the patron

Theodosius oversaw the removal in 390 of an Egyptian obelisk from Alexandria to Constantinople. Known today as the Obelisk of Theodosius, it still stands at the Hippodrome, once the center of Constantinople public life and a scene of political confusion. Re-erecting the monolith was a challenge to the technology that had been honed in the construction of siege weapons. The obelisk, still recognizable as a solar symbol, had been moved from Karnak to Alexandria along with what is now the Lateran obelisk of Constantius II. The Lateran obelisk was shipped to Rome soon after, but the other spent a whole generation lying on the docks because of the difficulty of trying to ship it to Constantinople, and then the obelisk broke up in transit to that city. The white marble base is entirely covered by bas-reliefs documenting the Imperial household and the engineering feat of moving it to Constantinople. Theodosius and the imperial family are separated from the nobles among the spectators in the imperial box with a covering over them as a sign of their status. The naturalism of traditional Roman art in such scenes gave way in these reliefs to a conceptual art: the idea of order, decorum and respective rank, expressed in tight rows of faces. In this way it begins to show that formal themes begin to supersede the transitory details of mundane life, celebrated in pagan portraits. Christianity had just been adopted as the new state religion.

The Forum Tauri in Constantinople was renamed and redecorated as Theodosius' forum, including a column and triumphal arch in his honor.

Religious politics

Orthodoxy and Arianism

In the fourth century century, the Christian Church was divided by controversy over the divinity of Jesus Christ, his relationship with God Father and the nature of the Trinity.

In 325, Constantine I convened the Council of Nicaea, which affirmed that Jesus, the Son, was equal to the Father, one with the Father, and of the same substance (homoousios in Greek). The council condemned the teachings of the theologian Arius who believed that the Son was created inferior to God the Father, and that the Father and the Son were of a similar substance (homoios in Greek) but not identical (see Antitrinitarianism), affirmed that God the Father created the Son. This meant that the Son, although still seen as divine, was not equal to the Father, because he had a beginning and was not eternal. Father and Son were, therefore, similar but not of the same essence. This Christology spread rapidly through Egypt and Libya and the other Roman provinces. Despite the council's decision, the controversy continued. At the time of Theodosius' accession, there were still various ecclesiastical factions promoting an alternative Christology.

Although none of the leading clerics within the Empire, who used the Nicene formula homoiousios, explicitly adhered to Arius, presbyter of Alexandria (Egypt), or his teachings, there were still some who tried to evade the debate by simply saying that Jesus was like (homoios in Greek) God the Father, not to speak of substance (ousia). All of these non-Nicenes were frequently referred to as Arians, that is, followers of Arius, by their opponents, although they would not have identified themselves as such.

The Emperor Valens had favored the group using the formula homoios; this theology was prominent in much of the East and, under Constantius II, became established in the West, being ratified by the Council of Rimini, though later abjured by most Western bishops, after Constantius II's death in 361. Theodosius, for his part, closely followed the Nicene creed, which was the dominant interpretation in the West and held by the important church of Alexandria.

On November 26, 380, two days after arriving in Constantinople, Theodosius expelled the non-Nicene bishop, Demophilus from Constantinople, and made Meletius patriarch of Antioch, and Gregory Nazianzus, one of the Cappadocian Fathers of Antioch (today in Turkey), Patriarch of Constantinople. Theodosius had just been baptized, by Bishop Acolius of Thessalonica, during a severe illness, as was common in early Christianity.

On February 27, 380, he, Gratian, and Valentinian II issued an edict for all their subjects to profess the faith of the bishops of Rome and Alexandria (ie, the Nicene faith). The edict was primarily an offensive against the various faiths that had arisen out of Nicene Christianity, such as the Macedonians, Arians, Anomeans, and Novatians. The exact text of this decree, collected in Codex Theodosianus XVI.1.2, was:

It is our desire that all the various nations which are subject to our Clement and Moderation should continue in the profession of that religion which was transmitted to the Romans by the divine Apostle Peter, as it has been preserved by the faithful tradition and which is currently professed by the Pontiff Damasus and by Peter, Bishop of Alexandria, a man of apostolic holiness. According to the apostolic teaching and doctrine of the Gospel, we believe in a single deity of the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit, in equal majesty and in a holy trinity. We authorize the followers of this law to assume the title of Christian Catholics; but as far as others are concerned, for in our judgment they are foolish, we decree that they be marked with the ignominious name of heretics, and they cannot pretend to give their conventes the name of churches. They will first suffer the reproof of divine condemnation and secondly the punishment of our authority which according to the desire of Heaven will decide to inflict.Henry Bettenson (1967, p. 22)

In May 381, Theodosius convened a new ecumenical council in Constantinople to repair the schism between East and West on the basis of Nicene orthodoxy. "The council went on to define orthodoxy, including the third person of the Trinity, the Holy Spirit, as equal to the Father and "proceeding" of Him, while the Son was "begotten" of Him". The council also "condemned the Apollinarian and Macedonian heresies, clarified the ecclesiastical jurisdictions according to the civil boundaries of the dioceses and decided that Constantinople was second in precedence to Rome".

With the death of Valens, the protector of the Arians, their defeat probably damaged the prestige of the Homoian faction.

Attitude towards paganism

Theodosius appears to have adopted a cautious policy toward non-Christian traditional cults, reiterating his Christian predecessors' prohibitions on animal sacrifice, divination, and apostasy, while allowing other pagan practices to take place publicly and temples to remain. open. He also expressed support for the preservation of the temples, but failed to prevent some damage caused by fanatics.

There is evidence that Theodosius was careful to prevent the empire's still substantial pagan population from becoming ill-disposed towards his rule. There is evidence of the appointment by Theodosius of a moderate pagan who would ensure protection for the temples in the eastern provinces, but that he would not seek revenge against the Christians either.

During his first official tour of Italy (389–391), the emperor won over the influential pagan lobby of the Roman Senate by appointing its leading members to important administrative posts, including Eutolmius Tatian and Quintus Aurelius Symmachus as consuls.

Preservation of temples

While Theodosius is commonly accused of being "anti-pagan," allowing or even participating in the destruction of temples, recent archaeological discoveries have undermined this view. Archaeological evidence of the violent destruction of temples in the IV and early 5th centuries throughout the Mediterranean is limited to a handful. of sites. The destruction of the temple is attested in 43 cases in the written sources, but only 4 of them were confirmed by archaeological evidence.

Of these 43 cases, the most remembered is the destruction of the gigantic Serapeum of Alexandria by fanatics in 392, according to Christian sources authorized by Theodosius (extirpium malum), it must be seen in contrast with a complicated background of less spectacular violence in the city: Eusebius mentions street fights in Alexandria between mixed bands of Christians and non-Christians as early as 249, and non-Christians had participated in the fights for and against Athanasius in 341 and 356. "In 363 Bishop George was killed for repeated acts of overt scandal, insult, and looting of the city's most sacred treasures."

Although it is noted in 393 as the last year that the Olympic Games were held. But archaeological evidence indicates that some of these Games were still taking place after that date. According to the classicist Ingomar Weiler, there are reasons to conclude that the Olympic Games continued after Theodosius and ended under Theodosius II due to lack of budget for its realization, going on to be held privately on a smaller scale. Two scholia connect the end of the games with a fire that he would have burned the temple of Olympian Zeus in 426, during the latter's reign.

Theodosian Code

According to The Cambridge Ancient History, the Theodosian Code of Laws (Theodosian Decrees or Theodosian Code) is a set of laws, originally dated from Constantine to Theodosius I, which were collected, arranged by subject, and republished throughout the empire between 389 and 391. Historians Jill Harris and Ian S. Wood explain that, in their original forms, these laws were created by different emperors. and governors to solve the problems of a particular place at a particular time. They were not intended as general laws.

One of the many problems with using the Code of Theodosius as a record of history is described by archaeologists Luke Lavan and Michael Mulryan. They explain that the Code can be seen to document "Christian ambition" but not the historical reality. The overtly violent 4th century century that one would expect to find when taking the laws at face value is not supported by archaeological evidence at all. the Mediterranean.

It is also worth noting the growing influence of Ambrose, Bishop of Milan, on the Code. It is worth noting that in 390, Ambrose had excommunicated Theodosius, who had recently ordered the massacre of 7,000 inhabitants of Thessalonica, in response to the assassination of their military governor established in the city, and that Theodosius carried out several months of public penance. The excommunication was temporary and Ambrosio would not readmit him until Theodosius did not show public repentance, with which the bishop demonstrated his authority before the emperor.

"End of Paganism"

Historian R. Malcolm Errington writes that reconstructing Theodosius I's religious policies is more complex than earlier historians thought. The image of Theodosius as "the most pious emperor," who presided over the an end to paganism through aggressive law enforcement and coercion, a view that, according to Errington, "has dominated the European historical tradition almost to the present day," was first penned by Theodoret who, in Errington's opinion, was in the habit of ignoring the facts and picking out "some specific pieces of legislation". paganism, but modern historians see this more as a later interpretation of the story by Christian writers than a true story. Averil Cameron explains that since Theodosius's predecessors Constantine (baptized at the bed of e death by the Arian Eusebius), Constantius and Valens had been Semi-Arians, it fell to the orthodox Theodosius to receive most of the credit from the Christian literary tradition for the eventual triumph of Christianity. Numerous literary sources, both Christian and pagan, attribute to Theodosius – probably by mistake, possibly on purpose – initiatives such as the withdrawal of state funding from pagan cults (this measure belongs to Gratian) and the demolition of temples (for which there is no evidence in legal codes or archaeology).

The increased variety and abundance of sources has led to reinterpretation of the religion of this era. According to Michele Salzman: "Although the debate over the death of paganism continues, scholars generally agree. I agree that the once-dominant notion of pagan-Christian religious conflict cannot fully explain the texts and artifacts or the social, religious, and political realities of late ancient Rome".

Scholars agree that Theodosius compiled extensive legislation on religious subjects and that he continued the practices of his predecessors, forbidding sacrifices with the intent of fortune-telling in December 380, issuing a decree against heretics on January 10, 381 and an edict against Manichaeism in May of that same year. Harries and Wood commented: "The contents of the Code give details of the canvas, but they are an unreliable guide, in isolation, to the character of the image as a whole& #34;. Previously underappreciated similarities in language, society, religion, and the arts, as well as current archaeological research, indicate that paganism slowly declined and was not forcibly overthrown by Theodosius I in the IV.

Maijastina Kahlos writes that the Empire of the IV century contained a wide variety of religions, cults, sects, beliefs, and practices, and that they generally coexisted without incident, although violence did occasionally occur, but such outbreaks were relatively infrequent and localized. 'In ancient times, not all religious violence was so religious, and not all religious violence was so violent.'

The Christian church believed that victory over "false gods" it had begun with Jesus and was completed with the conversion of Constantine; it was a victory that took place in heaven, rather than on earth, as Christians were only 15–18% of the empire's population in the early 300s. Salzman indicates that as a result of In this 'triumphalism', paganism was seen as vanquished and therefore heresy was a higher priority than paganism for Christians in the 4th and 5th centuries.

Myles Patrick Lavan says Christian writers gave the victory narrative high visibility, but it doesn't necessarily correlate with actual conversion rates. There are many signs that a healthy paganism continued into the 6th century and, in some places, into the VII and beyond. Archeology indicates that in most regions remote from the imperial court, the end of paganism was gradual and not traumatic. Peter Brown notes that even Jewish communities lived through a century of secure coexistence.

While acknowledging that Theodosius' reign may have been a turning point in the decline of the old religions, Cameron downplays the role of 'copious legislation' in the reign of Theodosius. of the emperor as of limited effect, writing that Theodosius "certainly not" he outlawed paganism. In his 2020 biography of Theodosius, Mark Hebblewhite concludes that Theodosius never saw or promoted himself as a destroyer of ancient cults; rather, the emperor's efforts to promote Christianity were cautious, 'targeted, tactical, and nuanced', and intended to prevent political instability and religious discord.

Death

Theodosius died in Milan of vascular edema on January 17, 395. Ambrose arranged for his burial in a Milan estate and delivered a panegyric entitled De Obitu Theodosii before Stilicho and Honorius in which detailed the suppression of heresy and paganism. His mortal remains were definitively transferred to Constantinople on November 8, 395. The Orthodox Church recognizes him as a saint.

Contenido relacionado

28th century BC c.

Franz Waxmann

International Civil Aviation Organization