The stain

La Mancha is a natural, historical region and/or macroregion located in the autonomous community of Castilla-La Mancha, in central Spain, which occupies part of the current provinces of Albacete, Ciudad Real, Cuenca and Toledo. It has an extension of more than 30,000 km², approximately 300 km from east to west and 180 km from north to south, constituting one of the most extensive highlands and natural regions of the Iberian Peninsula. It represents the southeastern end of the Central Plateau, specifically the South Subplateau.

The origin of the place name is unknown, although several sources affirm its Arab origin, although from different etymologies. One would suppose that the place name "Mancha" would be pronounced in Arabic as Manxa or Al-Mansha, which translates as "land without water", and another as Manya, translated as "high plain" or "high place". The Arabic word Manxa, according to the first theory, would have the meaning of "land of esparto grass, dry", being linked to the former Campo Espartario, taken from Carthagena Espartera, heiress in turn to the Roman province of Carthaginense. Its name is Manchego/a.

After the Christian Reconquest, between the 11th and 13th centuries, the territory of La Mancha acquired the structure that would mark it in the following centuries. Under Castilian sovereignty, for the most part within the kingdom of Castile into which the old kingdom of Toledo was subsumed, western Manchego was dominated by the powerful military orders of Santiago, Calatrava and San Juan, while its eastern area, The so-called Mancha de Montearagón, was controlled by the also powerful dominion (later marquisate) of Villena. It was the Catholic Monarchs who finally dominated the orders of Santiago and Calatrava when the Catholic King Fernando de Aragón became master of both, and also who turned a good part of the territory of the Marquesado de Villena into royalty. The Order of San Juan would not come under royal control until 1802, and the last lordships would survive until well into the 19th century.

The publication and success of the two novels by Miguel de Cervantes about Don Quixote de la Mancha in 1605 and 1615, most of whose adventures and actions take place in its extensive plains, have given fame and worldwide fame to this territory and its name. Traditionally agricultural, La Mancha also gives its name to prized agricultural products, such as Manchego cheese and the sheep breed from which it comes, wine, saffron and La Mancha melon.

La Mancha is first part of the crown of Castilla and then of Spain, despite having its own cultural characteristics and forming a natural region with historical tradition. In the Middle Ages there was a Común de la Mancha, and in 1691 a province of La Mancha was created, whose capital was Ciudad Real, which varied in size until its final disappearance in 1833, but none of these entities included all the territories already considered then as manchegos. In the 19th and 20th centuries, a timid Manchego regionalism arose, without lasting political significance. Since 1982, practically all of La Mancha has been circumscribed to the autonomous community of Castilla-La Mancha, whose limits notably transcend those of La Mancha.

Political geography

Modern definition of La Mancha

La Mancha is a natural region in central Spain, located to the south of the Central Plateau, which constitutes one of the most extensive highlands of the Iberian Peninsula. Its limits are imprecise, although it is generally accepted that its extension is more than 30,000 km², and that it covers part of the provinces of Albacete, Ciudad Real, Cuenca and Toledo.

One of the most accepted definitions of La Mancha is provided by Pascual Madoz in his work Geographical-statistical-historical dictionary of Spain and its overseas possessions (1848):

the terr. called Mancha, undoubtedly embraces the country, generally plain, raso and arido, contained from the mountains of Toledo to the western stribes of the Sierra de Cuenca, and from the Alcarria to Sierra-morena; entering into this understanding, what is called the table of Ocaña and the Quintanar, the part of Belmonte and San Clemente, the earth of the Santend. from E. to O. and 33 from N. to S.: until the sixteenth century, the eastern part of this earth. it was called Mancha de Montearagon and Mancha de Aragon [... ]; everything else was simply called Mancha: then the Blade was divided in Alta and Baja, according to its difference of level and course of the waters: the Alta understands the NE part: from Villarrubia de los Ojos to Belmonte, country of the Ant. laminican villages; and the Lower the SO part. including the fields of Calatrava and Montiel, country of the Ant. oretanos.

Similar descriptions of La Mancha would be made years later by José de Hosta (1865), or the Espasa encyclopedia.

Madoz (1848) also delimited La Mancha according to the territorial division of the moment:

According to the current civil division, the sterling of the wick corresponds to 4 prov. The City-Real almost entirely is in this demarcation (V.) and that is why it remains vulgarly known with the name of prov. de la Mancha: that of Toledo has in the same its eastern part, that is, the part of Ocaña, Madridejos, Lillo and Quintanar: that of Cuenca, those of Belmonte and San Clemente; and that of Albacete, those of Alcaráz and La Roda.

However, Madoz's description excludes from La Mancha territories and localities to the east that are generally considered to be from La Mancha, such as La Manchuela, and the surroundings of Albacete, Chinchilla de Monte-Aragón and Almansa. According to the study Around the concept and limits of a forgotten place-name: La Mancha de Montaragón by the historian Aurelio Pretel Marín (1984), these localities and territories are part of the historic Mancha de Montearagón, as well as the region of Hellín. In the same study by Pretel Marín (1984), the historically Castilian towns of Requena (in the province of Valencia), Villena and Sax (in the province of Alicante) are also included on the eastern edge of La Mancha de Montearagón.), and the Murcian region of Yecla, although at present territories outside the provinces of Albacete, Ciudad Real, Cuenca and Toledo are not usually considered to be from La Mancha. The same situation is applicable to the South, where towns such as Beas and Chiclana belonged to the province of La Mancha, but since they currently belong to the province of Jaén, they are not usually considered La Mancha.

Sometimes, La Mancha Alta is expanded to include towns in the Toledo region of La Sagra, such as Esquivias, and even Madrid, which has often been described as a poblachón or Manchego place.

There are also much more reductionist descriptions of La Mancha, such as the one carried out by Félix Pillet and Miguel Panadero in their studies for a geographical region of Castilla-La Mancha (which they divide into mountain ranges, of transition and of plains), and in which they limit La Mancha to “a large region or subregion of Castilla-La Mancha”, turning it into a region of plains that would encompass 15,900 km² and more than 90 municipalities. They present as separated from La Mancha, as transition regions, Campo de Calatrava, Campo de Montiel, Tierra de Alarcón, La Manchuela and the Almansa Corridor, and as sierra regions, the Valley of Alcudia and -dividing the Sierra de Alcaraz into two territories-, that of Alcaraz, in the western zone and that of Segura in the eastern zone.

Historical evolution of the place name Mancha and its understanding

There are several theories about the origin of the place name Mancha. There are those that relate it to the same Latin origin of the Spanish word "stain" (macŭla), but more establish an Arabic origin of the word. Some relate it to the Arabic word "manxa", translated as "dry land", but more probability[citation needed] to its origin from the Arabic word "mányà", which has been translated as &# 34;high plain", "high place" and "plateau".

Another, much older theory also suggests that La Mancha comes from Arabic. The theory arises from the historian Jerónimo Zurita who affirms that another historian, Pero López de Ayala, had certain news of the name of Mancha as a land of esparto grass, dry, that the Goths called it Spartaria and that the Arabs kept the lexicon Spartaria that in Arabic language would be Manxa. This Spartan land is linked to the old Campo Espartario or Espartaria, from Carthagena Espartera, heir in turn to the Roman and Visigothic province of Carthaginense, which included a large part of present-day Castilla-La Mancha.

In any case, the first recorded mentions of the place name Mancha date from the year 1237, and occur in agreements between the orders of San Juan and Santiago. In one case, it is about the layout of the limits of both Orders: «Then the Ruidera had the friars of Uclés, and they left in the middle with La Moraleja by rope, and from this milestone to the Mancha de Haver Garat, as long as it reaches the other milestone that is between Criptana and Santa María, and from this milestone that is between La Moraleja and La Roidera the valley runs up the road that goes from La Ruidera to Alhambra and returns to the Pozo del Allozo». In the other, it is a payment in heads of cattle from the commander of the Order of Santiago to that of San Juan, in compensation "for the help of the Guadiana water that I took from the Mancha de Montearagón."

Apparently, the Mancha de Haver Garat refers to the later Mancha de Vejezate, a region in which today are towns such as Tomelloso and Socuéllamos, and which had as its center the now uninhabited Torre de get old The Mancha de Montearagón, originally "of Montaragón", would point to the territory extended from the Ruidera lagoons to the east, through which it "mounted" towards Aragón, up to the kingdom of Valencia, which at that time was under full conquest by the King of Aragon, Jaime I.

In 1282, Don Manuel, lord of Villena, received from what would become King Sancho IV of Castile the extensive terms of Chinchilla, Jorquera and Ves, in La Mancha de Montearagón. Over time, and the expansion of these domains to Hellín and Tierra de Alarcón, according to the conclusions of Pretel Marín (1984), the geographical concept of La Mancha de Montearagón and the political concept of the Señorío (and later Marquesado) of Villena they would tend to be confused and identified.

On the other hand, in 1353, the Master of the Order of Santiago, Don Fadrique, in response to the request of various towns in the area under the jurisdiction of his Order, created the Common of La Mancha, including territories of the Mancha de Vejezate, with possessions between the Guadiana and Gigüela rivers and head in Quintanar de la Orden. Between 1478 and 1603 the following towns are described as belonging to the Común de La Mancha:

- In the present province of Ciudad Real: Alcázar de San Juan, Campo de Criptana, Arenales de San Gregorio, recently segregated, is included), Pedro Muñoz, Socuéllamos and Tomelloso.

- In the present province of Cuenca: Los Hinojosos, Horcajo de Santiago, Mota del Cuervo, Pozorrubio, Santa María de los Llanos, Villaescusa de Haro and Villamayor de Santiago.

- In the present province of Toledo: Cabezamesada, Corral de Almaguer, Miguel Esteban, La Puebla de Almoradiel, Quintanar de la Orden, El Toboso, La Villa de Don Fadrique and Villanueva de Alcardete.

However, the concept of La Mancha at that time and in subsequent centuries was not limited to the Común de La Mancha and the Marquesado de Villena, but rather it is more extensive, although not as extensive as it would be later. In the 1670s, in the Topographical Relations of Felipe II, in addition to the towns of the old common Santiago, then already divided, the towns of Campo de San Juan also say they are in La Mancha. On the other hand, they are not The towns of Campo de Montiel do the same, of which only Membrilla claims to be in La Mancha, nor do those of Campo de Calatrava, of which only four towns claim to be located in La Mancha. López-Salazar (2005) supposes that in the case of Campo de Calatrava, the link to Calatrava's maestrazgo or Almagro's party had greater weight than the simple geographical reference, but also that la Mancha was not then "a place name of fortune". In fact, there were towns that said they were in La Mancha (Ballesteros and Tirteafuera) with fewer geographical reasons to justify it than others that did not (such as Daimiel or Manzanares). Similar circumstances occur in the Mancha de Montearagón, called by deformation at this time Mancha de Aragón, in which, in the same Relations of Felipe II, there are few places that they claim to be located in the same, preferring instead the denomination of the Marquesado (of Villena) even after its disappearance, according to Petrel Marín (1984), due to its greater importance as a political reality and for the refusal to call itself "of Aragón" of some towns that were never Aragonese but Castilian.

In 1605, three decades after Felipe II's Relations, Miguel de Cervantes published El ingenioso hidalgo don Quixote de la Mancha, and in 1615, his second part: Second part of the ingenious knight Don Quixote de la Mancha. It is a joke: the protagonists of his beloved books of chivalry in which he is inspired are natives of worthy countries or regions: Greece, France, Brittany, etc. (see). Saying that Don Quixote is from La Mancha is not an attack on this region, but a way of making the reader laugh at this character, boastful at the beginning of the novel. But the enormous success of the novel also meant, according to López-Salazar (2005), the "success of the place name" of the land in which it takes place and which is the homeland of the protagonist, Don Quixote. Said success of the place name would have also meant the extension of its limits.

In 1691 the province of La Mancha was created, incorporating the districts of Ciudad Real (which was its capital), Almagro (with all of Campo de Calatrava), Infantes (with all of Campo de Montiel) and Alcaraz. At first, however, it did not include territories of the old Común de La Mancha, nor of Campo de San Juan, nor of the so-called Mancha de Aragón, but it did include territories that transcended the geographical limits of the Manchegan plain, such as the Sierra de Alcaraz or the Almaden area. In 1785, various towns of the Mesa del Quintanar (the former Común de La Mancha) would be incorporated into said province, and in 1799 the party of the great Priory of San Juan would do so (that is, the entire Campo de San Juan). This provincial division reached deep roots (López-Salazar, 2005), which did not prevent reform attempts during the War of Independence, the Liberal Triennium and, finally, the reign of Isabel II. In 1833 the territories of the old province of La Mancha were distributed among the provinces of Jaén (in a small portion), Cuenca, Toledo, Albacete and, above all, Ciudad Real, which would motivate this province to be popularly known for a while. as "province of La Mancha".

Descriptions of La Mancha such as that of Madoz date from the XIX century, which leaves out a good part of the Mancha de Montearagón, in the provinces of Cuenca and especially Albacete. In this regard, it should be remembered that the province of Albacete was attached to the Region of Murcia since its creation in 1833, and a good part of its territory was previously attached to the province of Murcia (definitively from the territorial division of the count of Floridablanca de 1785), following a political tradition that, however, did not imply the verification of a true geographical or cultural unity with Murcia, which is why it was unpopular in a good part of the current province of Albacete. On the contrary, the provinces of Ciudad Real, Cuenca and Toledo were integrated into the region of Castilla la Nueva together with the provinces of Guadalajara and Madrid. In that same century and in the following, a regionalist movement from La Mancha was born that claimed the creation of a La Mancha Region that would integrate the four La Mancha provinces (Albacete, Ciudad Real, Cuenca and Toledo), which would not obtain fruits.

During the Spanish Transition, with the division of Spain into autonomous communities, and after deep debates about its extension and name, the autonomous community of Castilla-La Mancha was created, which integrated the provinces of Albacete, Ciudad Real, Cuenca, Guadalajara and Toledo. Although this autonomous community includes several regions that have never been linked to La Mancha, it is common, despite being an error, to find references to the community of Castilla-La Mancha as " in the media and in everyday speech.;La Mancha" and abbreviate the name of the community, "castellano-manchego", to "manchego".

There is currently no official administrative Mancha, so the extension of the place name depends on the area in which it is used. There tends to be an overlapping of geographical, cultural and historical elements, which would include Mancha Alta (with the Mesa del Quintanar, Mesa de Ocaña and Campo de San Juan), Mancha Baja (with Campos de Calatrava and Campos de Montiel) and La Mancha de Montearagón, but with some limits not specially defined. There are, however, several protected designations of origin and geographical indications that use the name of La Mancha (DO La Mancha (wine), La Mancha saffron and La Mancha melon) or its name (Manchego cheese and Manchego lamb)., whose production areas, in any case, do not coincide.

History

Prehistory and Antiquity

Prehistoric remains in La Mancha are not scarce, however, in-depth studies of the deposits in the area are scarce. There are abundant Paleolithic deposits on the surface, mainly around the rivers, which originally could have been seasonal camps. The Guadiana and its tributaries make up an area that is especially rich in deposits of this type. As an example, in the Upper Guadiana area dominated by the courses of the Córcoles and Sotuélamos rivers and the Cañada de Valdelobos there is a large concentration of Middle Paleolithic sites. Similar concentrations can be found in the middle course of the Guadiana. As for Paleolithic Art, you can find some cave paintings such as the schematic figures of Fuencaliente, vaguely similar to those of the eastern peninsula.

During the Neolithic and the Bronze Age, the so-called Motillas Culture developed in the southern and central zone (east of Ciudad Real and west of Albacete). This sedentary civilization was characterized by the construction of settlements made up of dwellings packed into belts of concentric walls, which formed various staggered levels, giving the settlement the appearance of an artificial hill and facilitating its defense against invasions. Subsequently, the area suffered the successive invasion of Indo-European peoples and later received influences from the Iberian culture, especially in Albacete and Ciudad Real, where it is worth mentioning the multiple and important sites and towns existing throughout the province of Albacete such as the Cerro de los Santos, the Llano de la Consolación, Pozo Moro, El Amarejo or the Iberian towns of Alarcos and Cerro de las Cabezas, in Valdepeñas. Within this Hispanic culture, ancient authors classify the two peoples that inhabited the region of La Mancha (despite its also strong Indo-European influence), the Oretanos (with a nucleus in Oretum, present-day Granátula de Calatrava, in Ciudad Real) and the carpetanos of the course of the Tagus, whose main city was Toletum (present-day Toledo), consecrated to the god of the waters Tolt. They were towns of ranchers, farmers, and fierce warriors. The first historical references in the region are those of the wars between the Carthaginians and the indigenous peoples, shortly before the Second Punic War. The main reason for these wars was the possession of the Sisapo mines (today La Bienvenida), the largest mercury deposit in the world, which has been one of the motor axes of La Mancha until the 1950s. 70 of the last century.

The Romans, who conquered Toletum in 193 B.C. C., they called this great extension, according to some theories, "Campo Espartario" (probably due to the cultivation of esparto grass), although others relate this place name exclusively to the Cartagena area (at that time, Carthago Nova, and later Carthago Spartaria). Strabón speaks extensively about this region and tells in his Geography that in the time of Augustus some very important works were carried out on the old Roman road that went from Rome to Gades (present-day Cádiz). They made a detour close to the coast to avoid passing through the Campo Estepario that they considered to be long and arid, and probably also to avoid the guerrilla actions of the locals, which lasted long after the end of the Roman conquest. During this period the cities were of little importance, highlighting Laminium, Libisosa, Toletum, Segóbriga, Sisapo and Oretum. With the arrival of Christianity, Toledo and Oretum became bishoprics.

Middle Ages

When the dominance of the Roman Empire fell in the area, in the 5th century AD, the Vandals and Alans passed by, after which the Visigoths imposed their dominance, establishing the capital of their kingdom in Toledo in the year 569. At this time, however, large areas of La Mancha remained uninhabited.

In the year 711, the Arabs crossed the Strait of Gibraltar and began the conquest of the Iberian Peninsula, which they would call Al-Andalus. Precisely, according to various theories, it is from the Arabic language that the place name "Mancha" comes from: thus, Manxa or Al-Mansha translates as "land without water", and Manya as "high plain" or "elevated place", these being the most common theories about the origin of the place name. Under Muslim rule, La Mancha remained largely sparsely populated, although some cities appeared and developed, such as Toledo, Cuenca or Alcaraz, which became important centers of the textile industry. The Arabs also contributed enormously to the region's agriculture thanks to their advanced irrigation techniques, as well as livestock, with the introduction of the Merino sheep.

After the rupture of the Caliphate of Córdoba, most of La Mancha came under the control of the Taifa of Toledo, which had to face the taifas of Seville and Murcia for control of the Manchego territory. The Castilian intervention in aid of the Toledans culminated in the surrender of the city of Toledo in 1085, which began the Christian Reconquest of La Mancha, when the Kingdom of Castile seized its northern area. However, Castilla had to face the Almoravids, who were called for help by the other taifas, unifying Al-Andalus. La Mancha then became a continuous battlefield, with frequent incursions from both sides, and little human population. The maximum Almoravid control came after the battle of Uclés, in 1108, which forced the Castilians to retreat to the Tagus. In 1144 the decomposition of the Almoravid Empire began, which culminated in the second kingdoms of taifas, although the arrival of the Almohads soon took place. This situation led to the Christian advance through the Manchego territory, Calatrava being taken in 1147 and its defense entrusted in 1158 to Raimundo de Fitero, founder of the Order of Calatrava. However, the Castilian defeat against the Almohads in the Battle of Alarcos, in 1195, caused the withdrawal of the Order and the paralysis of the Christian reconquest, which was resumed in 1212 with the Battle of Las Navas de Tolosa. The following year King Alfonso VIII created the Alfoz de Alcaraz, thus almost all of La Mancha would be definitively under Castilian control, as well as the Guadalquivir valley, whose repopulation was given priority over that of La Mancha, much of it of which it remained under the control of the military orders. Thus, Campo de Calatrava came under the control of the Order of Calatrava (in the middle of whose domains Alfonso X the Wise founded Villa Real, present-day Ciudad Real, in 1255 to counteract the power of the order); the Order of San Juan took over Campo de San Juan; and, considerably reducing the territory of Alcaraz, the Order of Santiago, headquartered in Uclés, seized a good part of La Mancha Alta and Campo de Montiel. A few decades later it would take for the eastern area of La Mancha to be reconquered, La Mancha de Montaragón, whose first mention is from 1237, at the same time as the first mention of la Mancha de Haver Garat, the which constitute the first records of the place name Mancha. Most of the Mancha de Montearagón would remain during the 13th and 14th centuries under the control of the Señorío de Villena (after passing the Tierra de Alarcón to its power), however the eastern area of Campo de Montiel, as well as the Sierra de Alcaraz, they would remain within the limits of the Alfoz de Alcaraz, the land of Alcaraz being part of the so-called Eastern Mancha due to the indissoluble union between plains and mountains both by orography and by roads. On the other hand, the Order of Santiago divided its territories into three common: the Common of Uclés, the Common of La Mancha and the Common of Montiel. The commons were associations of towns in the same jurisdiction for fiscal and livestock purposes.

As part of the kingdoms of Toledo and Murcia (in its southeastern part), both integrated into the Crown of Castile, La Mancha was the scene and suffered the consequences of the Castilian civil wars that took place in the following centuries, and As a border area between Castilla and the Crown of Aragon, it was also the scene of the struggles between the two. The First Castilian Civil War took place between 1351 and 1369, between the supporters of King Pedro I the Cruel ( the Justiciero , according to his supporters) and those of the middle his brother, the bastard Enrique de Trastámara. This war was also mixed with the Hundred Years War between France and England, and with the War of the two Pedros (1356-1369), between Pedro I of Castile and Pedro IV of Aragon. The war ended in the middle of Mancha, with the Battle of Montiel, in 1369, in which Enrique killed his brother Pedro de él and became the new king of Castile, Enrique II. As a consequence of the war, the new king converted the Señorío de Villena into a Marquesado (the first in the history of Castile), which he granted to Alfonso de Aragón the Elder in 1366, confirming it in the courts of Burgos in February 1367, position which he could not carry out due to his capture in the hands of the English during the battle of Nájera on April 3, 1367. To the effects on the population of the wars, we must add those of the plagues, which affected almost all of Europe in the XIV century.

Also in the 15th century was Castile, and with it La Mancha, a place where clashes broke out between the different factions of the kingdom, which culminated in the War of the Castilian Succession, which pitted the supporters of Juana la Beltraneja, daughter of Enrique IV the impotent (or, according to rumors,, of the valid Beltrán de la Cueva), with the supporters of Enrique's sister, Isabel. Specifically, in Manchego territory, the Marquis of Villena (Diego López Pacheco), the Grand Master of the Order of Santiago (Juan Pacheco, father of the Marquis of Villena) and the Master of the Order of Calatrava (Rodrigo Téllez Girón, nephew of Juan Pacheco) supported Juana la Beltraneja. Faced with these, led by Alcaraz (March 1475), various towns of the Marquis rose up and clashes broke out within the Orders themselves. The war became international when Juana was married to Alfonso V of Portugal and Isabel to the heir to the Aragonese throne, Fernando. The war ended in 1479 with the Treaty of Alcáçovas, which led to the victory of Isabel and Fernando, who years later would be called the Catholic Monarchs. After the war, the Marquesado de Villena lost a large part of its territory, becoming royal, while Fernando the Catholic was elected master of the Order of Calatrava and assumed the administration of the Order of Santiago. It was precisely the Catholic Monarchs who created institutions such as the Holy Brotherhood and the Inquisition, and conquered the Nasrid Kingdom of Granada in 1492, putting an end to Muslim rule in the Iberian Peninsula, and with it the dangers of attacks by Moors in the south of La Mancha.

Modern Age

Already in the XVI century the last of the Castilian wars took place. After the accession to the throne of Carlos I of Spain, son of Juana I of Castilla, la Loca, and grandson of the Catholic Monarchs, he surrounded himself in his government with Flemings, which earned him enemies. In 1520, revolt broke out in several Castilian cities, which marked the beginning of the War of the Communities of Castile. Toledo became one of the main centers of the revolt, which demanded the return of the throne to Juana among other measures. The war ended with the defeat of the comuneros in 1522. In 1523, Pope Adriano VI forever united the masterships of the military orders of Santiago and Calatrava to the Crown of Spain.

After the revolt of the Moors in the Rebellion of the Alpujarras (1568-1571), in which they were defeated, Felipe II ordered their dispersal throughout Castile, including La Mancha, although they would finally be expelled in 1609. It is also in the XVI century, in which windmills, responsible for grinding grain, spread throughout a large part of La Mancha of the cereal It is in these years that Miguel de Cervantes immortalized the society of the time and the La Mancha region in his work Don Quixote de la Mancha, giving it universal fame. The first part of the book would be published in 1605, and the second in 1615. During the 16th and 17th centuries, La Mancha, like the rest of Spain, would suffer the effects of the continuous wars abroad under the reign of the House of Austria..

Between 1701 and 1714, the War of the Spanish Succession took place, in which the territories of the Crown of Castile supported Philip of Anjou and those of the Crown of Aragon supported Archduke Carlos of Austria. La Mancha, as a border territory with Aragon, experienced decisive battles, such as the battle of Almansa. Finally, the war resulted in the victory of Felipe V. Under the reign of the Bourbons, during the XVIII century, these they were faithful to the policy of enlightened despotism.

In 1691 it was decided to segregate the province of La Mancha from the rest of the Kingdom of Toledo, incorporating the districts of Alcaraz, Almagro, Ciudad Real and Infantes, to facilitate its administration. The capital was located in Ciudad Real, although for a brief period it passed to Almagro (1750-1761). With the territorial planning of Floridablanca, of 1785, the towns of the Order of Santiago in Mesa de Quintanar were added to the province of La Mancha, and in 1799 the towns of the Great Priory of San Juan, separated from the province of Toledo. With the territorial planning of Floridablanca, the provinces of Toledo and Cuenca were also configured, while the province of Murcia was expanded to the northwest, occupying a good part of the current province of Albacete. The provinces of La Mancha, Cuenca and Toledo, together with those of Guadalajara and Madrid, formed the region of Castilla la Nueva.

In 1802, Carlos IV proclaimed himself Grand Master of the Order of San Juan in Spain and incorporated his territories into those of the Crown.

Contemporary Age

Between 1808 and 1813, the Spanish War of Independence took place. La Mancha suffered the effects of the war, in which the French forces were fighting to defend King Joseph I, imposed by Napoleon, against the patriot guerrillas, who were fighting for the restoration of Ferdinand VII to the throne. The conflict of Valdepeñas and the Battle of Ciudad Real stood out as warlike events in this war.

In La Mancha, as in other parts of Spain, a Junta arose, the Junta Superior de la Mancha, against the Frenchified administration. Between 1811 and 1812, this Board published a Gazette of the Superior Board of La Mancha, successively from Elche de la Sierra, Alcaraz and Ciudad Real.

During the war, there were attempts to reform the provincial order of Spain. The Frenchified administration established a division based on prefectures without historical bases in 1810; in addition to making the town of Manzanares the capital of La Mancha, subdividing the territory into two sub-prefectures, that of Ciudad Real and that of Alcaraz. Faced with it, the Cortes of Cádiz created a new provincial division in 1813. Neither of the two divisions was put into practice after the return of Fernando VII in 1814, and with which absolutism also returned.

After the pronouncement of Rafael de Riego in 1820, the liberals assumed power. In 1822 a new provincial arrangement was approved, in which the province of La Mancha disappeared, replaced for the most part by that of Ciudad Real, and in which the new province of Chinchilla appeared, made up of territories from the old provinces of La Mancha, Cuenca and Murcia. However, the Liberal Triennium fell in 1823 (and with it its provincial ordination), after the military intervention of the One Hundred Thousand Sons of San Luis, at the request of Fernando VII, and which was followed by intense persecution of the Liberals.

On the death of Ferdinand VII in 1833, he was succeeded by his daughter Isabel II. However, her mother, the regent María Cristina de Borbón-Dos Sicilias had to rely on the liberals, against the supporters of Carlos María Isidro de Borbón, brother of Fernando VII, for whom they claimed the throne. Already in that year the provincial division was carried out that established the current provinces of Albacete, Ciudad Real, Cuenca and Toledo, and that supposed the definitive disappearance of the province of La Mancha. Ciudad Real, Cuenca, Toledo, Madrid and Guadalajara formed the region of Castilla la Nueva, and Albacete and Murcia the Region of Murcia. The only later modifications of these provinces were the passage from Villena de Albacete to Alicante in 1836, the passage from Villarrobledo from Ciudad Real to Albacete in 1846, and the passage from Requena and Utiel from Cuenca to Valencia in 1851.

Throughout these years, the definitive abolition of lordships in Spain also took place.

During the Carlist Wars (1833-1840, 1846-1849, 1872-1876), La Mancha remained mostly faithful to the Government of Madrid, that is, to the liberal cause. However, this did not prevent the actions of some Carlist forces, which came to take some towns, as in the case of El Bonillo by the Carlist general Cabrera. Carlism had special strength in the north of the province of Cuenca. At the same time, there was a rise in banditry.

During the 19th century, La Mancha was one of the regions of Spain most affected by confiscations, among which those of Mendizábal and Madoz stood out.

With the fall of Isabel II after the Revolution of 1868, a meeting of representatives of the Federal Republican Party took place in Alcázar de San Juan in which the Manchego Regional Pact was signed. However, in the draft Federal Constitution In 1873, the creation of a State of La Mancha was not contemplated, but of a state of Castilla la Nueva and another of Murcia. However, in 1873, during the Cantonal Revolution, in Ciudad Real there was an uprising that proclaimed the Manchego Canton, which failed, like the rest of the cantonal revolt in Spain. Federal hopes were cut short with the fall of the Federal Republic in 1874. Manchego regionalism later manifested itself in the creation in 1906 in Madrid of the Manchego Regional Center, which even created a flag and an anthem of La Mancha, and He defended the creation of a La Mancha Region, made up of the provinces of Albacete, Ciudad Real, Cuenca and Toledo. With the Provincial Commonwealth Decree of 1913, the legal possibility of establishing a Manchegan Commonwealth made up of these provinces was given, something that was demanded in 1919 by the Magna Assembly of the Manchegan Central Youth in Madrid, and which came to propose the Provincial Council of Albacete in 1924, without final results. After the proclamation of the Second Spanish Republic in 1931, there were meetings of deputies, and in 1933, of presidents of the four provincial councils, to study the possibilities of creating a region of La Mancha endowed with a Statute of Autonomy. These possibilities were cut short by the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939), during which almost all of Manchego's territory remained under the control of the Republic until the end of the war. During the Franco regime, in 1962, the Interprovincial Union Economic Council of La Mancha was established, with the purpose of coordinating the provincial councils of the four provinces.

After the Transition to democracy, Spain was divided into autonomous communities. In 1982 the creation of the Autonomous Community of Castilla-La Mancha was formalized, made up of the provinces of Albacete, Ciudad Real, Cuenca, Guadalajara and Toledo. At present, there are no electorally relevant regionalist parties from La Mancha. However, some institution of the autonomous community only includes the four "Manchegan provinces": thus, the university district of Castilla-La Mancha does not include Guadalajara, which is integrated into that of Madrid; and the Caja Castilla-La Mancha was formed by the merger of the savings banks of the provinces of Castilla-La Mancha, excluding the Caja de Guadalajara.

Physical geography

Geomorphology

La Mancha constitutes an extensive plateau, basically flat, with an average altitude between 600 and 700 meters above sea level, formed by Miocene sediments, mainly limestone and marly, but also clayey, and conglomeratics of the Plio-Quaternary glacis, which They form some witness hills and cover the Paleozoic base of quartzite and phyllite, visible in the Alcudia valley, as well as the Pleistocene rañas on the volcanic lava flows of Campo de Calatrava, to the west. To the southeast, on the other hand, it is worth noting the carbonate-marly Mesozoic system of the Montiel field and the Alcaraz mountain range. The Sierra de Alcaraz, historically linked to La Mancha, instead presents steep slopes and high altitudes, its highest peak being Almenaras, at 1,798 meters above sea level.

Hydrography

La Mancha is divided between the Tagus, Guadiana and Guadalquivir basins by the Atlantic slope; and the Júcar and Segura basins on the Mediterranean slope.

The main rivers that bathe La Mancha, in addition to the Tagus, Guadiana and Júcar, are their tributaries. The Gigüela or Cigüela stands out, a tributary of the Guadiana on the right bank, its tributaries, the Riansares and the Záncara, and the tributary of the latter, the Córcoles river. On the left bank of the Guadiana, the Azuer and Jabalón rivers stand out. And the Cabriel, a tributary of the Júcar on the left bank, should also be highlighted.

Other important rivers are the Mundo River, a tributary of the Segura on the left bank, and the Guadalmena, Guadalén and Jándula rivers, tributaries on the right bank of the Guadalquivir, although all these rivers flow through the mountains that surround La Mancha, not by the Manchego plain itself.

There are also important wetlands in La Mancha, among which stand out the Tablas de Daimiel (declared a national park) and the Lagunas de Ruidera (declared a natural park), both in the Guadiana, and very important for a wide range of bird life. The Pedro Muñoz-Mota del Cuervo marsh complex, the Pedro Muñoz lagoon, the Alcázar de San Juan lagoons, the Alcahozo lagoon and the Manjavacas lagoon are also very important for fauna. All these parks and lagoons are part of the Wet Spot, declared a biosphere reserve by Unesco.

Climate

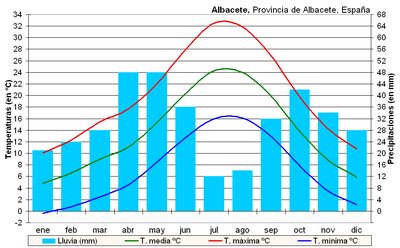

La Mancha has a continental Mediterranean climate. The most significant factors in this regard are: harsh winters, hot summers, summer drought, irregular rainfall, strong temperature fluctuations, and notable aridity. These features are the result of the interrelationships between some geographic factors and other dynamic ones such as latitude, the situation of the region within the peninsula, the layout of the relief and altitude.

The temperatures are very extreme due to the effect of continentality, the annual thermal amplitude (difference between the average temperature of the coldest month and that of the hottest month) is very high, normally between 18 and 20 °C. In July the average monthly temperature is above 22 °C in most of the region.

The winters, however, are cold, with an average temperature in January that is even below 4 °C in certain areas (Belmonte 3.4 °C), and frosts are frequent in winter and even in early spring and late fall.

Precipitations are between 300 and 400 mm per year most of the year, being more frequent in spring and autumn, and very scarce in summer. For all these reasons, most of La Mancha can be included in the so-called "Dry Spain".

Demographics

Distribution and density of the population

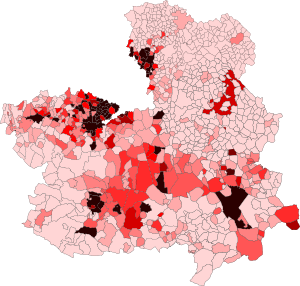

Compared to other areas of Spain (with an average population density of 93.39 inhabitants/km² in 2013), La Mancha is sparsely populated, with a low population density, and a high concentration of it in around large towns and small cities separated from each other by relatively long distances (sometimes 10 or 20 km). This concentration of the population around small cities and large towns is especially intense in central La Mancha, specifically in the center and northeast of the province of Ciudad Real, southeast of the province of Toledo and northwest of the province of Albacete, and in to a lesser extent the southwest of the province of Cuenca; with cities such as Tomelloso (with 38,900 inhabitants in 2013), Alcázar de San Juan (31,973 inhabitants) and Valdepeñas (30,869 inhabitants), among others, by Ciudad Real; Villarrobledo (26,513 inhabitants) and La Roda (16,398 inhabitants) by Albacete; and Quintanar de la Orden (11,704 inhabitants), Madridejos (11,113 inhabitants) and Consuegra (10,668 inhabitants), among others, by Toledo. The largest town in central La Mancha in the province of Cuenca is San Clemente (7,463 inhabitants). Only Albacete (172,693 inhabitants), Ciudad Real (74,872 inhabitants) and Puertollano (51,550 inhabitants) exceed 50,000 inhabitants (the cities of Talavera de la Reina, Guadalajara, Toledo and Cuenca, the other Castilian-La Mancha cities that exceed said number of inhabitants, are not part of La Mancha). These are the areas with the highest population density in La Mancha, which go from around 50 inhabitants/km² in northeastern La Mancha, Ciudad Real, to around 30 inhabitants/km² when moving towards the East.

Smaller populations that determine lower population densities present the Mesa de Ocaña and La Manchuela, around 20 inhabitants/km², and even lower ones occur in the entire geographical area of Montiel, the Alcudia valley and the mountainous areas, with population densities of less than 10 inhabitants/km². There are spikes in population density in areas located at the extremes of La Mancha, such as in areas of the same Mesa de Ocaña (Ocaña, 11,016 inhabitants) and in Tarancón (16,071 inhabitants), close to Madrid, and in Almansa (24,837 inhabitants) (and also in the Campos de Hellín (Hellín, 30,592 inhabitants), which are not usually considered La Mancha), near the Valencian and Murcian Levant.

Evolution of the population

The population in La Mancha grew during the first half of the 20th century due to the natural growth of the population, but in the decades of the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s of that century there was an intense process of rural exodus, which led to to an even greater concentration of the population in the large towns and provincial capitals and to the emigration of a large part of the population, especially the youngest, to other more industrialized regions, such as Madrid, Catalonia and Valencia, and even to abroad. As a result, the population of La Mancha decreased in these decades, while the aging of the population in rural areas intensified. In the 1980s and 1990s, the process of rural exodus slowed down, allowing a slight population growth, which intensified in the last five years of the century XX and in the first decade of the XXI century due to increased foreign immigration.

Economy

La Mancha has traditionally been an agrarian region, with industry and an economy generally less developed than the Spanish average.

Agriculture and livestock

Agriculture and livestock have historically been the main economic activities of La Mancha. In the agriculture of La Mancha, dry farming stands out, especially the so-called "Mediterranean trilogy": cereal, vine and olive tree. Among the cereals, the most cultivated are wheat and barley.

As for the vine, the La Mancha vineyards are the largest in the world by area. The La Mancha Denomination of Origin extends over these lands, which extends through part of the provinces of Albacete, Ciudad Real, Cuenca and Toledo. It occupies 190,980 ha and 182 municipalities, making it the largest wine denomination of origin on the planet. However, the La Mancha Denomination of Origin is not the only denomination of origin for wines in the region: others are added to it, such such as the D.O. "Valdepeñas", "Manchuela", "Ribera del Júcar", "Uclés" and "Almansa".

Saffron cultivation also stands out in La Mancha, which has its own Protected Designation of Origin, which covers 315 municipalities, including the entire province of Albacete and parts of the provinces of Ciudad Real, Cuenca and Toledo.

Another crop that has a Protected Geographical Indication is melon. The PGI "Melon from La Mancha" It covers 13 municipalities in the province of Ciudad Real: Alcázar de San Juan, Arenales de San Gregorio, Argamasilla de Alba, Campo de Criptana, Daimiel, Herencia, Llanos, Manzanares, Membrilla, Socuéllamos, Tomelloso, Valdepeñas and Villarta de San Juan..

Other products with designation of origin are olive oil from Campo de Montiel, eggplant from Almagro, and purple garlic from Las Pedroñeras.

As for livestock, sheep stand out, which together with goats have constituted transhumant herds from which wool, milk and meat have been obtained for centuries.

Precisely, Manchego sheep's milk is used to produce the famous Manchego cheese, which has its own denomination of origin, just as Manchego lamb meat has a Protected Geographical Indication. Both extend through part of the provinces of Albacete, Ciudad Real, Cuenca and Toledo.

They are also of some importance, although to a much lesser extent than sheep, pig and cattle.

Industry, mining and services

La Mancha does not have a great industrial tradition. Currently, the largest industrial centers in La Mancha are located around Albacete, Ciudad Real and Puertollano, as well as food industries spread throughout its geography.

Mining has been especially important in Puertollano, with its important coal mines, and in Almadén, whose cinnabar (mercury ore) mines have been exploited since Roman times.

The service sector, during the XX century, became, as in the rest of Spain, the key sector of the Mancha economy. Within the services sector, the growth of tourism can be highlighted, especially rural tourism.

Culture

Architecture

The towns of La Mancha, which are usually large and far apart, are sprawling, with houses generally consisting of floor and floor plans. They are usually organized around a main square, where the church and town hall are usually located. The church is usually the most outstanding building in the towns of La Mancha, and is normally made of stone, and may present mixtures of architectural styles. The houses are usually always whitewashed, that is, whitewashed, and their roof is usually gabled, with curved tiles. Also typical of La Mancha's popular architecture are windmills, stone huts and cuckoos, and inns and inns.

The popular Manchego architectural style is preserved in monumental main squares of various towns in Manchego, but in many towns it has been lost in recent decades.

Speak

The only language spoken in La Mancha since the culmination of the Reconquest is Spanish or Castilian. However, the speech of La Mancha presents its own dialectal characteristics, which distinguish it from other varieties of the language. It is considered a transition speech between the northern Castilian dialect and the southern dialects of the Iberian Peninsula (Andalusian, Extremaduran and Murcian dialects).

The Manchego dialect, although it does not represent a fully uniform speech, does present aspects that unite it, and at the same time separate it from other Castilian dialects. One of its most characteristic features is the aspiration of the postvocalic s, sounding like voiced /h/ or even /x/ (the sound of the letter J in Spanish). This, and the total absence of leísmos and laísmos, distinguishes it especially from Northern Castilian. It differs from the more southern variants, among other aspects, in the much less profusion of aspirations or elisions of s and z, and in the full distinction of s and z.

The speech of La Mancha also presents a rich lexicon and expressions of its own, made up of phonetic variations of standard Castilian words, archaisms, words from the Mozarabic, Arabic and Latin substratum, influences from other languages and nearby dialects (given frequent catalanisms and valencianisms, aragonesisms and andalusisms), different meanings for words that already exist in standard Castilian, or words that are fully their own, in some cases even typical of only a few towns.

There is a wiki about this way of speaking and its vocabulary centered on the town of Tomelloso, La Tomepedia.

Literature and theater

La Mancha owes much of its universal fame to the novel by Miguel de Cervantes, Don Quixote de la Mancha, written in two parts, the first published in 1605 and the second in 1615, whose The action takes place mainly in La Mancha, the homeland of the protagonist, Alonso Quijano, a poor hidalgo who goes crazy reading books of chivalry and believes he is a knight-errant, calling himself Don Quixote. The novel itself, and the characters, especially Don Quixote, Sancho Panza and Dulcinea del Toboso, as well as other elements that appear in the novel, such as windmills, have become authentic symbols of La Mancha, with many towns in dispute. of the region being the place of La Mancha that Cervantes did not want to remember.

Don Quixote is not, however, the only aspect of the literature of the Spanish Golden Age that remains in La Mancha, where one of its main exponents, Francisco de Quevedo, also lived his last years, who died in Villanueva de los Infants. In Almagro, a 17th century playpen is preserved, a symbol of the importance of theater at the time, and where the International Classical Theater Festival is held every year.

A literary description

Benito Pérez Galdós, in Bailén (1873), left written this essential impression of the country of La Mancha:

"This way we go through La Mancha..., solitary country where the sun is in its kingdom, and man seems to be the exclusive work of the sun and dust; country among all famous since the whole world has become accustomed to assuming the immensity of its plains traveled by the horse of D. Quixote. (...) This is the truth: the Blae, if any beauty has, is the beauty of its whole, is its own nakedness and monotony, that if they do not distract or suspend the imagination, they leave it free, giving it space and light where it is precipite without stumbling. The greatness of Don Quixote's thought is understood only in the greatness of the Blade. In a monstrous, fresh, green country, populated with pleasant shadows, with beautiful houses, flowery orchards, temperate light and thick atmosphere, D. Quixote could not exist, and would have died in flower, after the first exit, without astonishing the world with the great exploits of the second. D. Quixote needed that horizon, that land without roads, and that, however, all of it is the way; that land without directions, because by it it goes to all parts, without going to any particular thing; land arising out of the paths of the adventure, and where all that happens has to appear the work of the accident or of the genius of the fable solitude; it needed to represent the transparent "Benito Pérez Galdós

Festivities and traditions

The festivities associated with the main events of the Christian calendar are common in the cities and towns of La Mancha, such as:

- El Carnaval, being of national tourist interest that of Villarrobledo, that of Herencia and that of Alcázar de San Juan, and of regional tourist interest those of Tarazona de la Mancha, Miguelturra, Villafranca de los Caballeros and the Domingo de Piñata de Ciudad Real. In many localities there is the tradition of merendar in the countryside on Thursday Lardero.

- The Holy Week, being of international tourist interest Hellín, of national tourist interest those of Tobarra, Ocaña, Ciudad Real and Albacete, and of regional tourist interest the Living Passion of Tarancón and the Game of the Caras of Calzada de Calatrava.

- The Corpus Christi, being of national tourist interest the Sins and Dancers of Camuñas, and of regional tourist interest the Corpus Christi of Villanueva de la Fuente y las Alfombras de Serrín de Elche de la Sierra.

- The Assumption of the Virgin, the day on which the feasts are common in many Manchegos villages.

- Christmas.

The patron saint festivities in honor of the town's patron saint are also very important. Of these, we must highlight the Albacete Fair (in honor of the Virgen de los Llanos), of international tourist interest. The Patron Saint Festivities of San Bartolomé in Tarazona de la Mancha, the Bring and Carry of the Virgin of Manjavacas in Mota del Cuervo, La Diablada de Almonacid del Marquesado and the Moors and Christians Festivities of Almansa are of national tourist interest. Regional tourist interest are the Fiestas de la Pandorga in Ciudad Real, the Fiesta de las Paces in Villarta de San Juan, the festival of Vitor de Horcajo in Santiago (considered the longest procession in Christianity), the Fiestas de Rus de San Clemente, and the Dancers and the Holy Christ of the Beam of Villacañas. Sometimes these festivities are accompanied by a pilgrimage in which the saint, Christ or Virgin is moved from the town's main church to a sanctuary or hermitage, and vice versa. Fairground attractions are also often installed and folkloric dances and songs are performed.

Other festivities originate from the use of farm and livestock resources, such as harvesting and harvesting (such as the grape harvest), or the slaughter of pigs (or mataero). The Fiesta del Olivo de Mora is of national tourist interest, and the Fiestas de la rosa del azafrán de Consuegra are of regional tourist interest. It is also common in many towns in La Mancha to sing the mayos on the night of April 30, the best known being those of Pedro Muñoz, of national tourist interest. The May Crosses of Villanueva de los Infantes are also of regional tourist interest.

Gastronomy

Manchegan gastronomy is rich and varied, although austere and humble, normally adapted to the scarce resources of the land and the climatic rigors of the region. Many of the dishes contain vegetables, some almost exclusively (apart from the essential olive oil), such as ratatouille from Manchego, moje, alboronía or asadillo from La Mancha. Some of the most recognized vegetables are Almagro aubergines and garlic, especially those from Las Pedroñeras.

When dishes from La Mancha incorporate meat, they are usually lamb (raised in abundance in the area), pork, or small game (from species such as rabbits, hares and partridges). Examples of these dishes are the Manchego stew or the tojunto. Among the products made with game meat, the pickled partridge should be highlighted. Products from the slaughter of pigs are chorizos, black pudding (in the province of Ciudad Real, due to Extremaduran influence, patatera is also produced), ribs, orza loin or imperial sausage. Duels and griefs are made with some of these products, and the production of ajo mataero is typical of the day of the pig slaughter. A dish with similar ingredients is the mortaruelo.

There are also several dishes based on cereals, such as porridge from La Mancha, migas ruleras or ajoharina. The well-known Cruz bread is also made with wheat flour, as well as the cenceña cake. With the latter, in combination with game meat, Manchego gazpachos are made.

It is common to use potatoes in cooking, with which dishes such as somallao, tiznao or atascaburras are made. The last two are made with one of the few fish present in traditional La Mancha cuisine, due to its easy preservation, given the distance from the sea: salted cod. Other common fish are those from the river, such as trout. Also ingredients of La Mancha gastronomy are legumes, present in stews, or mushrooms, such as guiscanos (this is how níscalos are known locally). Common seasonings are saffron, and aromatic herbs, such as rosemary or thyme.

Manchego cheese, appreciated all over the world, is made from Manchego sheep's milk.

All these dishes can be accompanied by regional wines. Wine is also the base of other traditional drinks, such as cuerva and zurra.

La Mancha pastries are rich in pan fruits, such as fried flowers, flakes, pestiños, fried milk, French toast, knee or fritilla tortilla, or rolls. They are also prepared biscuits, such as the drunken sponge cake or the Alcázar cakes, and in areas of Ciudad Real the wafers are typical. In the province of Albacete, made in La Roda, the miguelitos are very typical.

Music and dance

The typical song and dance of La Mancha are the seguidillas from La Mancha; although since La Mancha has always been a region of meetings, those others are also considered as varieties: the jota manchega, the torrás, the malagueñas, the fandangos, the rondeñas, the round songs, the fifth songs, the songs of laboreo, the mayos, or the aguilanderos or carols, among others. This music is accompanied by different musical instruments, such as the Spanish guitar, the bandurria, the lute, the dulzaina and the drum, the castanets or false, the zambomba or the tambourine (the latter especially for the Christmas carols), and even simple instruments that were not created for musical use, such as the bottle of anise, the pestle or the cane and the sticks used in the paloteo dance.

Contenido relacionado

Scotland

January

Flag