The name of the rose

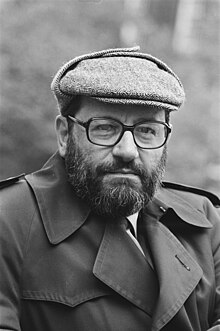

The Name of the Rose (original title Il nome della rosa in Italian) is a historical mystery novel written by Umberto Eco and published in 1980.

Set in the turbulent religious environment of the XIV century, the novel narrates the investigation carried out by Friar William of Baskerville and his Melk's Adso ward around a mysterious series of crimes that take place in an abbey in northern Italy.

The great repercussion of the novel caused thousands of pages of criticism of The Name of the Rose to be published, and references have been pointed out that include Jorge Luis Borges, Arthur Conan Doyle and the scholastic William of Ockham.

In 1987 the author published Apostilles to The Name of the Rose, a kind of poetic treatise in which he commented on how and why he wrote the novel, providing clues that enlighten the reader about its genesis of the work, although without revealing the mysteries that arise in it. The Name of the Rose won the Strega Prize in 1981 and the 1982 Foreign Médicis Prize, entering the “Editors' Choice» of 1983 from the New York Times.

The great critical success and popularity acquired by the novel led to the making of a homonymous film version, directed by the Frenchman Jean-Jacques Annaud in 1986, with Sean Connery as the Franciscan William of Baskerville and Christian Slater incarnating his disciple, Adso.

Context

In his previous theoretical work, Lector in fabula, Eco already outlined in a footnote the «controversy over the possession of goods and the poverty of the apostles that arose in the XIV between the Spiritual Franciscans and the Pontiff". possibly heretical by both the papacy and the Dominicans. The intellectual figure of the nominalist William of Ockham, his empiricist and scientific philosophy, expressed in what has been called Ockham's razor, is considered part of the references that helped Eco to build the character of William of Baskerville, and determined the historical framework and the secondary plot of the novel.

According to Eco, if the Gruppo 63 had not existed, he would not have written The name of the rose. The Gruppo 63, movement of literary neo-avant-garde to which the author belonged, pursued an experimental search for linguistic forms and content that would break with traditional schemes. To them he owes "the propensity for 'another' adventure, a taste for quotes and collage". Applying his own literary theory, The Name of the Rose it is an opera aperta, an “open novel”, with two or more levels of reading. Full of references and quotes, Eco puts a multitude of quotes from medieval authors on the lips of the characters; the "naive" reader can enjoy it at an elementary level without understanding them, "then there is the second level reader who captures the reference, the quote, the game and therefore knows that, above all, irony is being done." Despite being considered a "difficult" novel, because of, or perhaps even because of, the number of citations and footnotes, the novel was a genuine popular success. In this regard, the author has put forward the theory that perhaps there is a generation of readers who wants to be challenged, who seeks more demanding literary adventures.

Eco's original idea was to write a detective novel, but his novels «never started from a project, but from an image. Hence the idea of imagining a Benedictine in a monastery who is struck down while reading the bound collection of the Manifesto." Widely familiar with and passionate about the Middle Ages from previous theoretical works, the author naturally transferred this image to the Middle Ages, and he spent a year recreating the universe in which the plot would take place: «But I remember that I spent a whole year without writing a single line. He read, made drawings, diagrams, in short, he invented a world. I drew hundreds of labyrinths and floors of abbeys, based on other drawings, and in places that I visited". In this way, he was able to familiarize himself with the spaces, with the routes, recognize his characters and face the task of finding a voice for himself. his narrator, which after reviewing those of the medieval chroniclers led him back to the citations, and for this reason the novel had to begin with a found manuscript. Eco says in this regard in Apostilles: «This is how I immediately wrote the introduction, placing my narrative at a fourth level of inclusion, within three other narratives: I say that Vallet said that Mabillon had said that Adso said...».

Synopsis

In a mental climate of great excitement I read, fascinated, the terrible story of Adso de Melk, and so much caught me that almost a pull I translated it into several large format notebooks from the Papeterie Joseph Gibert, those in which it is so nice to write with a soft pen. In the meantime, we arrived in the vicinity of Melk, where, at peak on a bend of the river, the beautiful Stift is still left, several times restored throughout the centuries. As the reader has imagined, in the monastery library I found no trace of Adso's manuscript.Umberto Eco. The name of the rose. Preface: Naturally, a manuscript.

It is the Middle Ages in the vicinity of the winter of 1327 under the papacy of John XXII. The Franciscan William of Baskerville and his disciple, the Benedictine novice Adso de Melk, arrive at a Benedictine abbey located in northern Italy and famous for its impressive library, which has strict access rules. Guillermo must organize a meeting between the delegates of the Pope and the leaders of the Franciscan order, in which they will discuss the alleged heresy of the doctrine of apostolic poverty, promoted by a branch of the Franciscan order: the spirituals. The celebration and success of said meeting are threatened by a series of deaths that the superstitious monks, at the behest of the blind ex-librarian Jorge de Burgos, consider to be in keeping with a passage from the Apocalypse.

William and Adso, evading the rules of the abbey at many times, try to solve the mystery by discovering that, in reality, the deaths revolve around the existence of a poisoned book, a book that was thought to be lost: the second book of Aristotle's Poetics. The arrival of the papal envoy and inquisitor Bernardo Gui begins an inquisitorial process of bitter memory for Guillermo, who in his search has discovered the magnificent and labyrinthine library of the abbey. Guillermo's scientific method is confronted with the religious fanaticism represented by Jorge de Burgos.

Characters from The Name of the Rose

William of Baskerville

He is an English Franciscan friar of the 14th century century, with a past as an inquisitor. Guillermo de Baskerville is entrusted with the mission of traveling to a distant Benedictine abbey to participate in a meeting that would discuss the alleged heresy of a branch of the Franciscans: the spirituals. This description and the coincidence in the name have led us to think that the character of William could refer to William of Ockham, who actually intervened in the dispute over apostolic poverty at the request of Miguel de Cesena, concluding that Pope John XXII was a heretic.. In fact, Eco initially considered Ockham as the main character instead of William of Baskerville. Also, in the novel these two have a friendly relationship.

Upon his arrival, given his reputation as a perceptive and intelligent man, the abbot commissions him to investigate the strange death of a monk to avoid the failure of the meeting. The novel's description of William is reminiscent of Sherlock Holmes: "His height of him was greater than that of a normal man and, as he was very gaunt, he seemed even taller. His gaze was sharp and penetrating; the sharp and slightly aquiline nose gave his face a watchful expression, except in moments of lethargy to which I will refer later ». As for the surname Baskerville, it also refers to the Arthur Conan Doyle novel starring Sherlock Holmes, The Hound of the Baskervilles, another noted reference. Guillermo also frequently chews the leaves of one or more plants unknowns that produce a psychoactive effect, a habit similar to that of Sherlock Holmes with cocaine.

Melk Adso

Narrator voice of the novel, he is presented as the son of an Austrian nobleman, Baron de Melk, who in the novel fought alongside Ludovico IV of Bavaria, Holy Roman Emperor. A Benedictine novice, while staying with his family in Tuscany, he is entrusted to Guillermo by his family as a scribe and disciple, and helps his mentor in the investigation. The character, as mentioned in the novel, shares a name with Adso de Montier-en-Der, a French abbot born in 920 who wrote a biography on the antichrist entitled De nativitate et obitu Antichristi and inspired by a certain way in Dr. Watson, the assistant of the detective Sherlock Holmes.

In an interview included in the DVD version of the film The Name of the Rose, its director, Jean-Jacques Annaud, assures that Umberto Eco told him that Adso is an "idiot", the which "does not understand his teacher" and that "in the end he did not understand anything. He has not understood the lesson of the teacher of him ».

Jorge de Burgos

The Spanish Jorge de Burgos is an old and blind monk, stooped and "white as snow", revered by the rest of the monks, who fear him as much as they respect him.

The one who had just spoken was a monk snared by the weight of the years, white as snow; I am not only referring to the hair but also to the face, and to the pupils. I understood he was blind. Although the body was already shrinking by the weight of the age, the voice remained majestic, and powerful arms and hands. He clad his eyes on us as if he were seeing us, and always, also in the days that followed, I saw him move and speak as if he still possessed the gift of sight. But the tone of the voice, instead, was that of someone who was only gifted of prophecy.Umberto Eco. The name of the rose.

The name of the character is a recognized homage to Jorge Luis Borges; Eco had in mind a blind man who would guard the library, and he comments in Apostilles that «... a blinder library can only produce Borges, also because debts are paid».

According to Umberto Eco, the character of Jorge had to be Spanish not only as a reference, due to his Hispanicity, to Jorge Luis Borges, but also because it was in Spanish lands where the most famous medieval miniatures and comments related to < i>Apocalypse. Jorge de Burgos significantly cites said book, copies of which appear abundantly in the section of the library dedicated to Hispania —among them reproductions of the Commentary on the Apocalypse by Beato de Liébana— brought to the abbey of the novel from Spain by Jorge together with the copy of the second book of Aristotle's Poetics, also made in Silos by a Spaniard or an Arab (see Islamic Contributions to Medieval Europe).

Historical figures

Ubertino da Casale

Ubertino da Casale (1259-c. 1330) was an Italian Franciscan religious, leader of the spirituals of Tuscany. In the novel he is introduced as a friend of Guillermo.

Michele de Cesena

The Italian Michael of Cesena (in Italian Michele da Cesena) (1270-1342) was a minister general of the Franciscan order and a theologian. He was a member of the "spiritual" Franciscans, who were at odds with Pope John XXII in the dispute over evangelical poverty. He appears in the novel as the leader of the Franciscan legation supported by Emperor Ludovico IV of Bavaria.

Bernardo Gui

Bernardo Gui or Bernardo Guidoni (1261/1262-1331) was a French Dominican religious, inquisitor of Toulouse between 1307 and 1323. In the novel he is presented as an inquisitor in command of the French soldiers in charge of the indemnity of the papal legation. He is portrayed as William of Baskerville's nemesis, which has been interpreted as an analogy to the relationship between Sherlock Holmes and Professor Moriarty.

Bertrando del Poggetto

Bertrand du Pouget (in Italian Bertrando del Poggetto) (c. 1280-1352) was a French diplomat and cardinal. He appears in the novel as the leader of the legation of the Avignon papacy.

Girolamo, Bishop of Caffa

Girolamo, bishop of Caffa is the name used in the novel to refer to Jerome of Catalonia, also known as Hieronymus Catalani, a Franciscan religious and the first bishop of Cafa (Crimea).

Other characters

- Adelmo da Otranto: New, illustrator and miniaturist.

- Venancio de Salvemec: Monje, translator of manuscripts, specialist in Greek and Arabic.

- Berengario da Arundel: English Monk, assistant librarian.

- Severino da Sant'Emmerano: German monk, herbal.

- Hildesheim Malachi: German Monk, librarian.

- Abbone da Fossanova: Abbot of the monastery.

- Blessing of Upsala: Scandinavian Monk, rhetoric student.

- Alinardo da Grottaferrata: Oldest Monk of Abbey.

- Remigio da Varagine: Monje cillerero, former member of the dulcinistas.

- Salvatore de Monferrato: Monje deforme, assistant of Remigio, former member of the dulcinists.

- Nicola da Morimondo: Glass Monk.

- Aymaro d'Alessandria: Monje chismoso and burlón, copista.

- Rábano de Toledo: Lighting Monk.

- Clonmacnois Patricio: Lighting Monk.

- Magnus de Iona: Lighting Monk.

- Pacific da Tívoli: Monje.

- Pietro de Sant'Albano: Monje.

- Gunzo da Nola: Monje.

- Hugo de Newcastle: English Franciscan theologian, member of the imperial legation.

- Bishop of Alborea: Religious Dominican, a member of the papal legation.

- Peasant of the village by the Abbey; Adso falls in love with her and never knows her name.

Analysis

Title

According to the author in Apostilles, the provisional title of the novel was The Crime Abbey, a title that he discarded because it focused attention on the police intrigue. His dream, he says, was to title it Melk's Adso , a neutral title, since Adso's character was no more than the narrator of events. According to an interview given in 2006, The Name of the Rose was last on the list of titles, but “everyone who read the list said that The Name of the Rose he was the best."

The title had occurred to him almost by chance, and the symbolic figure of the rose was so dense and full of meanings that, as he says in Apostilles: «he has almost lost them all: rose mystical, and as a rose it has lived what roses live, the war of the two roses, a rose is a rose, the Rosicrucians, thank you for the splendid roses, fresh rose all fragrance». For Eco, this lack of final meaning due to the excess of accumulated meanings responded to his idea that the title "should confuse ideas, not regiment them."

It's cold in the scriptoriumMy thumb hurts. I leave this text, I don't know who, this text, that I don't know what you're talking about anymore: stat rose pristina nomine, nomina nuda tenemus.Adso de Melk

The enigma of the title was added to the enigma of the Latin verse that closed the novel. In this regard, the author explains in Apostilles that, even if the reader had grasped the "possible nominalist readings" of the verse, that indication would come at the last moment, when the reader would have already been able to choose multiple and varied odds. He answers about the meaning of the verse, saying that it is a verse taken from a work by Bernardo Morliacense, a 12th-century Benedictine who composed variations on the theme of the ubi sunt, adding to them the idea that of all the glories that disappear all that remains are mere names.

There's only the naked name leftor

(Although) the name of the first rose persists, (only) the naked name we have.Bernardo Morliacense

Related to the title of the novel is also the poem by the New Spanish writer Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz that appears in the initial epigraph of the Apostilles to The Name of the Rose:

Rosa que al prado, incarnate,You're bragging.

You'll be unhappy too.

and carmine bathed:

Lozana countryside and tasteful,

but no, that being beautiful

Structure and narrator

According to the introduction, “Naturally, a manuscript”, The name of the rose is based on a manuscript that fell into the hands of the author in 1968, Le manuscript de Dom Adson de Melk, a book written by a certain "Abbé Vallet" found in the abbey of Melk, on the banks of the Danube, in Austria. The purported book, which contained rather poor historical indications, claimed to be a true copy of a 14th-century manuscript found in Melk Abbey.

From this base, the novel reconstructs in detail the daily life in the abbey and the rigid time division of monastic life, which articulate the chapters of the novel dividing it into seven days, and these into their corresponding canonical hours: Matins, Lauds, Prime, Terce, Sixth, None, Vespers and Compline. The effort put into achieving a suitable environment allows the author to repeatedly use Latin quotations, especially in scholarly conversations among the monks.

The story is narrated in the first person by the elderly Adso, who wishes to leave a record of the events he witnessed as a young man in the abbey. In Apostilles, Eco comments on a curious duality of the character: he is the eighty-year-old man who narrates the events that occurred in which Adso, the eighteen-year-old youth, intervened. «The game consisted of continually bringing the old Adso into the scene, reasoning about what he remembers having seen and heard when he was the other Adso, the young man. (···) This double enunciative game fascinated me and made me very excited». The narrative voice is, then, a voice passed through multiple filters; After the unavoidable filter of age and the years passed by the character, the introduction of the novel explains that the original text of Adso de Melk is registered by J. Mabillon, in turn cited by the Abbe Vallet, from whom the author would borrow the story. As Eco explained in Apostilles, this triple filter was motivated by the search for a medieval voice for the narrator, realizing that ultimately "books always speak of other books and each story tells a story that is already has counted".

Intertextuality

The name Adso has been considered a tribute to Simplicio, a character in Galileo Galilei's Dialogue Concerning the Principal Systems of the World (Ad simplicio, «for Simplicio») and the similarity with the character of Dr. Watson, companion of Sherlock Holmes, whom the protagonist, Guillermo de Baskerville, alludes to by name.

In the novel, an exposition of the scientific method and deductive reasoning is made, skilfully used by William to solve the mystery, sometimes recalling his performance both to Sherlock Holmes and to William of Ockham (c. 1280/1288 – 1349), Franciscan and English scholastic philosopher, pioneer of nominalism, considered by some to be the father of modern epistemology and philosophy in general.

There is also reference to book II of Aristotle's Poetics, which was apparently lost during the Middle Ages and of which nothing is known, although it is supposed (and the novel states so) that it dealt with comedy and iambic poetry. It is the book that in the novel causes the death of several monks.

Teodosio Muñoz Molina points out in Pending accounts between Eco and Borges several coincidences with The Eye of Allah, a story by Rudyard Kipling that Borges claimed to have read a hundred times times; also with another religious English detective, brother Cadfael, protagonist of the series of novels by Ellis Peters set in the 12th century. He later says that the novel:

... constitutes a so gigantic as justified centon that imbricates fragments of all the books of the Bible, from Genesis to Revelation; and, in a polychromatic and disproportionate textual mosaic, concurren promiscuously Plato, Aristotle, Ausonio, Boecio, Clement of Alexandria, St. Physyca kai mystica Gnostic Bolos Democrito and the Tabula Smaradigna of the nebula Hermes Trismegistos, to the Speculum Alchemiae Roger Bacon and the Tetragrammaton of the Catalan Arnaldo of Vilanova, not without having also sought the connivance of Averroes, of Avicena, of Abu-Bakr-Muhammad Ibn Zaka-riyya ar Razi and of the no less profuse anthroponymous of Geber Abu Musa Djabir Ibn Hajjam Al-Azid Al-Kufi Al-Tusi Al-Sufi.Theodosio Muñoz Molina. The pending accounts between Eco and Borges.

Echo and Borges

The figure of Jorge Luis Borges circulates through The name of the rose embodied in the character of Jorge de Burgos, both are blind, "venerable in age and wisdom", both of whom speak Spanish as their native language. In this regard, Eco wrote this in 1992 in a special in the newspaper Clarín dedicated to Borges:

Obviously, there is a kind of homage in The name of the roseBut not because I called my character Burgos. Once again we are faced with the reader’s temptation to always seek relations between novels: Burgos and Borges, the blind, etc. [...] Like the Renaissance painters, who placed their portrait or that of their friends, I named Borges, like that of so many other friends. It was a way of paying tribute to Borges.

Eco had been fascinated by Borges since he was twenty-two or twenty-three, when a friend lent him Ficciones (1944) back in 1955 or 1956, when Borges was still practically unknown in Italy. Precisely in < i>Fictions includes The Library of Babel, a short story by the Argentine writer that previously appeared in The Garden of Forking Paths (1941); Several coincidences have been pointed out between the library of the abbey, which constitutes the main space of the novel, and the library that Borges describes in his story: not only its labyrinthine structure and the presence of mirrors (recurring motifs in Borges's work)., but also that the narrator of The Library of Babel is an old bookseller who has dedicated his life to the search for a book that holds the secret of the world.

There are also Borgesian reminiscences in the title; In El golem (1964) Borges wrote, in the same sense as the final verse of the novel, that "the name is the archetype of the thing", and "in the pink letters is the rose".

The City of God

According to Gonzalo Soto Posada, Eco applies in The name of the rose one of the figures of classical rhetoric, the adynaton, and interprets the novel as a inversion of The City of God by Saint Augustine, written between 412 and 426, in which the concept of "heavenly city" is confronted with the "pagan city". In The City of God the knights of good build the "city of God" and values such as life, peace, love, justice... The knights of evil destroy that project, and flood the land of death, war, hate, injustice. In Eco's novel, the good knights, represented by Jorge de Burgos, are the murderers and destroyers, while Guillermo de Baskerville, the supposed heretic, is a builder, persecuted by Burgos and his henchmen .

This ideological confrontation revolves around a book, the second of Aristotle's Poetics, a manuscript that is supposed to have disappeared in the Middle Ages, and in which the philosopher supposedly made a defense of comedy and humor as a possibility to question the established absolutes. The character of Burgos represents here an authoritarian orthodoxy, clinging to the past, a paradigm of the Christian "I am the way, the truth and the life", confronted with Baskerville, who personalizes the culture of laughter, who questions orthodoxy, who proclaims "I seek the truth", considering that nothing is final and that everything must be reinterpreted and viewed with a healthy skepticism.

Laughter

Laughter as a subversive element is a triggering agent for the deaths that occur in the novel. In this regard, the Slovenian philosopher, psychoanalyst and cultural critic Slavoj Žižek wrote the following in his book The Sublime Object of Ideology:

What disturbs in The name of the roseHowever, it is the underlying belief in the liberating and antitotalitarian force of laughter, of the ironic distance. Our thesis here is almost exactly the opposite of this underlying premise in Eco's novel: in contemporary, democratic or totalitarian societies, that cynical distance, laughter, irony, are, so to speak, part of the game. The prevailing ideology does not intend to be taken seriously or literally. Perhaps the greatest danger to totalitarianism is the person who takes his ideology literally—even in the novel of Eco, poor George, the incarnation of dogmatic belief that does not laugh, is first of all a tragic figure: outdated, a kind of dead in life, a remnant of the past, and surely not a person representing the existing political and social powers.Slavoj Žižek (1992). The sublime object of ideology. Twenty-first century. ISBN 9789682317934.

Contemporary politics

Several authors have found correspondences between the plot of the novel and the bloc confrontation of the Cold War, the 20th century struggles between different factions within the political left, or in particular, in the Italian political environment that culminated in the assassination of Aldo Moro by the Red Brigades after the so-called "historic compromise": the political union agreement between the Italian Communist Party and the Christian Democrats.

Editing, reception and awards

In an interview published in 2006 by the Argentine newspaper Clarín, Eco comments that at first he thought of a discreet publication, of about a thousand copies, with a fine binding, in a different publishing house from the one he published. His works were usually published by the Bompiani publishing house, from RCS MediaGroup. However, the spread of the rumor that he was writing a novel led to several interested publishers turning to him, so he thought it no longer made sense to change publishers.

On July 9, 1981, eight months after the book was published, The Name of the Rose won the Strega Prize, Italy's highest literary award. In November 1982, the Spanish newspaper El País echoed the French Médicis Foreign Prize for Umberto Eco for the novel, advancing its next translation. The first edition in Spain, published in December of the same year, According to La Vanguardia critics, it was an excellent translation by Ricardo Pochtar, an experienced connoisseur of Eco, for Editorial Lumen.

In 1983 the edition in the United States had an excellent reception. The New York Times highlighted both the previous success in Europe and the excellent translation by William Weaver. Choice» of 1983 from the New York Times.

In 1995, the Mystery Writers of America included it in its list of the hundred best mystery novels of all time. In turn, in 1999 it was selected among "The 100 Books of the Century" by the French newspaper < i>Le Monde.

The great repercussion of the novel caused thousands of pages of criticism, hundreds of essays, books and texts of monographs to be published around The name of the rose. In 1985 the author published < i>Apostilles to The Name of the Rose, a book, like a poetic treatise, in which he commented on how and why he wrote the novel: «I have written Apostilles to avoid having to die, to avoid having to to answer new questions". the role of the reader as interpreter of the text, and postulated that the author should disappear, split from the work after its publication; for Eco the novel should be a "machine for generating interpretations" and it is not up to the author to facilitate them. For this reason, the same author explains that in Apostilles he provided clues that could enlighten the reader about the genesis of the work, an essay on the creation process, but that it does not really reveal any of the mysteries that are pose in the novel.

Published in thirty-five countries, by 2006 fifteen million copies of The Name of the Rose had been sold worldwide, five of them in Italy; After a good initial reception from critics, the popular success caused some subsequent distancing from it.

Adaptations and Inspiration

Cinema

The popular success achieved by Umberto Eco's first novel was similar to that achieved by its film version of the same title, directed by Jean-Jacques Annaud in 1986. However, Italian critics were very harsh on the film after its release in Florence, pointing out that it betrayed the book, or that it was not up to the literary work; one of the newspapers of the time titled his review "Great book, insignificant film"; Il Messaggero criticized that "desiring to win over a refractory North American public, they have ended up making a film that is not liked in the United States or in Europe".

In the film, Sean Connery played the Franciscan friar and former inquisitor of the 14th century, Friar William of Baskerville and a teenager Christian Slater embodied the also Franciscan Adso (Benedictine in the novel). It should be noted that the character of Salvatore was brought to life by Ron Perlman, a regular actor in Annaud's filmography.

Television

In 2019, the miniseries The Name of the Rose was produced for television, consisting of eight chapters, an Italian-German production created and directed by Giacomo Battiato. The series stars John Turturro as William of Baskerville and Rupert Everett as Bernardo Gui.

Games

In other media, the novel inspired the cult Spanish video game La abadía del crimen (1987), as well as its new version, titled La abadía del crimen Extensum (2016). Other adaptations to the video game are Nomen rosae (1988) and Il noma della rosa [sic] (1993), as well as the graphic adventure The Abbey (2008), which is loosely based on the novel. It has also inspired the board games The Mystery of the Abbey (1996) and The Name of the Rose (2008), as well as the conversational games In the name of the Lord and The Abbey of Montglane.

Contenido relacionado

Akutagawa Award

Quipu

History of Catalonia