The Adventures of Tintin

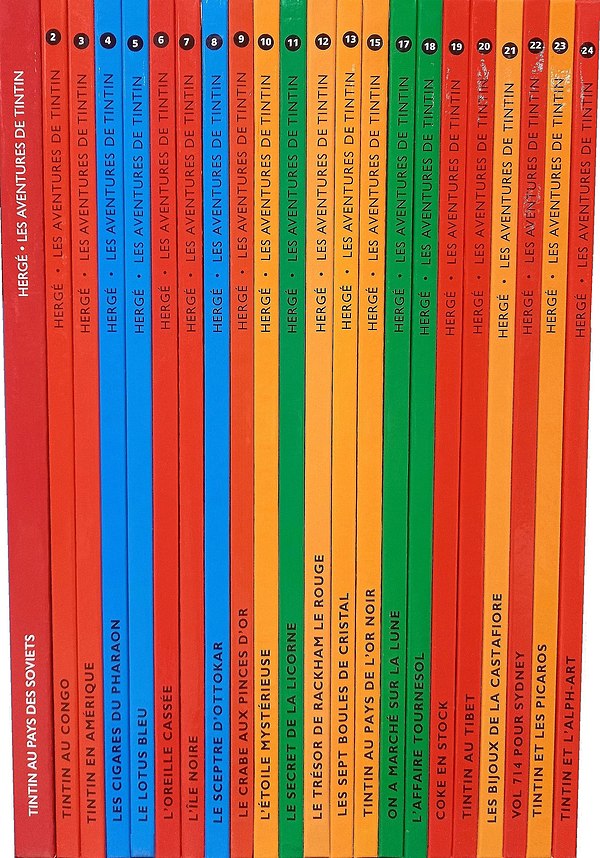

The Adventures of Tintin (whose original name in French is Les Aventures de Tintin et Milou) is one of the most influential European series of 20th century comics. Created by the Belgian author Georges Remi (Hergé), and characteristic of the graphic and narrative style known as "bright line", it is made up of a total of 24 albums, the first of which was published in 1930 and the penultimate in 1976, the last titled Tintín y el Arte-Alfa, was not completed, although the sketches made by the author were later published).

The first seven episodes of the adventures of Tintin were published serially in Le Petit Vingtième, a supplement to the Catholic-oriented Belgian newspaper Le Vingtième Siècle, between 1929 and 1939. (the publication of the eighth, Tintin in the Land of Black Gold, was interrupted in 1940 when the German invasion of Belgium occurred, although the author would resume it years later). Subsequently, Tintin's adventures appeared in other publications: the newspaper Le Soir, during the German occupation of Belgium, between 1940 and 1944; and the weekly Tintín, from 1946 to 1976. All of the character's adventures were later collected in independent albums and translated into numerous languages. Starting with The Mysterious Star (1942), the albums were always published in color, and the task of coloring and re-editing the previous albums in the series was also undertaken (with the exception of Tintin in the country of the soviets). Reissues sometimes affected the content of the albums.

In the series, along with Tintin – an intrepid reporter with a youthful appearance and an age that has never been clarified who travels around the world with his dog Snowy – there are a series of secondary characters who have achieved great celebrity: among them, the Captain Haddock, Professor Tornasol, detectives Hernández and Fernández and the singer Bianca Castafiore. The adventures of these characters are carefully set in real settings on the five continents, and in imaginary places created by Hergé, such as Syldavia or San Theodoros. Especially from the fifth album of the series (El Loto Azul ), the author of it thoroughly documented the places visited by his characters.

The series has enjoyed unprecedented success since its inception. It is estimated that more than 200 million albums have been sold since its inception in more than 60 languages, not counting pirated editions. The adventures of the character of Hergé are also an object of worship and collection throughout the world. Charles de Gaulle famously said that his only rival on the international level was Tintin. Tintin's fame has not been free of controversy, however, as some of the first albums in the series have received criticism for showing an anti-communist, colonialist and racist ideology.

History

Background

In 1928, Abbe Norbert Wallez, director of the Belgian newspaper Le Vingtième Siècle, made the decision to create a weekly supplement aimed at children and young people. He entrusted the direction of this supplement to one of the newspaper's employees, Georges Remi, who in 1924 had begun to use the pseudonym by which he would become known worldwide, Hergé.

The first issue of this supplement, which would bear the name Le Petit Vingtième, appeared on November 1, 1928. In its pages Hergé drew a comic series, The Extraordinary Adventure of Flup, Nénesse, Poussette and Cochonnet, with scripts by one of the sports editors of Le Vingtième Siècle. The unoriginal comic strip narrated the adventures of two twelve-year-old boys, the sister of one of them, six, and their pet, Cochonnet, a rubber pig. Convinced that the supplement needed a more innovative series that would connect with the youth audience, Hergé had the idea of creating a reporter, Tintin, whose first adventure would be a trip to the Soviet Union. On January 4, 1929, the newspaper published the announcement of the imminent publication of the adventures of Tintin, presented as a fictitious reporter for Le Petit Vingtième. Six days later, on January 10, the character began his journey in the pages of the supplement.[citation required]

Several models have been sought for Tintin, most of them made of paper and ink, although there are also some made of flesh and blood. The main one is, without a doubt, the boy scout Totor, a previous character of Hergé who appeared in the magazine Le Boy-Scout Belge since July 1926. Totor is the protagonist of which can be considered Hergé's first comic series, which bore the title Totor, chief of the bumblebee patrol (Totor, CP des Hannetons). The figure Totor's schematic is a prefiguration of Tintin, although the characteristic cowlick is missing. His attitude towards life, characteristic of the scout movement, is also very close to that of Hergé's main character. [ citation needed ]

The coincidence of name and the resemblance of Tintin to a character created in 1898 by Benjamin Rabier and Fred Isly, Tintin-Lutin, an eight-year-old boy who has a very long lock of hair, has also been pointed out. similar to that of Hergé's creature. According to his own testimony, however, Hergé did not know of the existence of this character until 1970 (Assouline, 1997, p. 40)

Hergé declared, for his part, that he had based himself on the physique of his brother, the soldier Paul Remi (Sadoul, 1986, p. 71). The character's profession as a reporter can also be attributed to his admiration for well-known journalists of the time, such as the Frenchman Albert London.

The fascist leader Léon Degrelle, alone and against all evidence, boasted on several occasions, especially in his book Tintin mon copain (1992), of having been the living model on which Hergé inspired to create his famous reporter. According to him, Tintin's trip to the country of the Soviets would be based on his trip to Mexico to cover the Cristero war as a reporter. This is impossible, since Degrelle traveled to Mexico months after the adventures of Tintin began to be published in Le Petit Vingtiéme. Pierre Assouline, Hergé's main biographer, flatly rules out this possibility. It is true, however, that, thanks to Degrelle, Hergé was able to discover several American comic series that had great influence on the subsequent development of his work, such as Bringing Up Father, by George McManus, or The Katzenjammer Kids, by Rudolph Dirks.[citation required]

First adventures (1929-1934)

Most likely, the fate of Tintin's first adventure was decided by Abbe Wallez, a fervent anti-communist: it was not just about entertaining youth, but about showing the dangers that communism entailed. Based on a book quite popular at the time that denounced these dangers, Moscou sans voiles ("Moscow without veils", 1928), by Joseph Douillet (Assouline, 1997, p. 42), Tintin in the Land of the Soviets narrates the foray of the reporter, already accompanied by his faithful pet, the fox terrier Snowy, into Soviet Russia, continually insisting on the perversities of the communist regime. Hergé's drawing is still quite rudimentary (Farr, 2002, p. 15), and clearly shows the influence of American cartoonists such as George McManus.

The comic was a great success among the Belgian public: when it finished publishing, in May 1930, Tintin's return to Belgium was staged at the North Station in Brussels. The character, represented by a fifteen-year-old boy scout, was received by a real crowd (Assouline, 1997, p. 45). Thanks to this great popularity, from that year on his adventures also began to be published in France, in a Catholic weekly, Coeurs Vaillants. That same year, other Hergé characters, Quique and Flupi, made their debut. appearance in the pages of Le Petit Vingtième.

Tintin's second adventure took place in the Belgian Congo, and is an open apology for the advantages of colonialism, with certain racist overtones. A paternalistic discourse about colonial domination predominates, current in Belgian society at the time. Some of the more controversial aspects of the album were removed in later editions. Despite this, the comic continues to be the subject of controversy, as demonstrated by the controversy caused by its recent reissue in the United Kingdom, in 2007.

At the end of Tintin's adventure in the Congo it is discovered that a group of Chicago gangsters, led by Al Capone, plans to take over the diamond business in the Congo, already anticipating the which would be the third of the reporter's adventures, Tintin in America. Indeed, in the following story, which began to be published in September 1931 in the pages of Le Petit Vingtième, the young reporter and his inseparable fox-terrier visit the United States, where the protagonist not only achieves thwart Capone's criminal plans, but also has time to pay a visit to the redskins, long idealized by Hergé since his time as a boy scout. For the first time, the character of Tintin decisively takes a stand for the rights of an oppressed minority, forcefully denouncing the abuse to which Indians are subjected in the United States.[citation required]< /sup>

In the next episode of his adventures, The Pharaoh's Cigars, initially titled "The Adventures of Tintin in the East", Tintin begins a journey that will take him to new exotic settings: Egypt; India and, later, on the next album, China. On this occasion the reporter is not traveling as an envoy for his newspaper, Le Petit Vigtième , but for reasons of pleasure. In The Pharaoh's Cigars the police officers Hernández and Fernández (Dupond et Dupont, in the original version) make their first appearance. The figure of the evil millionaire Rastapopoulos, who had already had a brief appearance in Tintin in America, takes center stage. Compared to previous adventures, the plot has been considerably enriched.[citation required]

The publication as an independent album of Los cigarros del pharaoh, in 1934, was carried out by the Casterman publishing house, which from then on would be in charge of publishing the adventures of the character (the first three volumes had been edited by Éditions du Petit Vingtième).[citation required]

On the eve of the Second World War (1934-1940)

The Blue Lotus, published in installments between December 1932 and February 1934, marks a turning point in the history of the series. Critics agree that it is Hergé's first masterpiece, and some authors consider it the best of all the Tintin albums (Farr, 2002, p. 51). Thanks to the collaboration of a Chinese student, Zhang Chongren, the album is meticulously documented, and is made with the explicit purpose of banishing absurd Western stereotypes about China. Furthermore, The Blue Lotus stands out for its denunciation of racism and colonialism, and for its open criticism of Japanese intervention in China, a burning issue at the time of its publication.

The creative maturity reached by the series after The Blue Lotus is shown in all its splendor in the following years, which coincided with pre-war tensions in Europe. During this stage, Hergé made three other albums, now considered classics: The Broken Ear, The Black Island and Ottokar's Scepter. A fourth, Tintin in the Land of Black Gold, would be interrupted when the German invasion of Belgium occurred in 1940, and would only be resumed several years later.[citation required]

The Broken Ear was published in Le Petit Vingtième between December 1935 and February 1937. The album marks the beginning of Hergé's fascination with Latin America, which he later It would be used as a setting in later adventures. The trigger of the plot is the theft from the Ethnographic Museum of an Arumbaya fetish (an Amerindian ethnic group invented by Hergé), in pursuit of which Tintin travels to the imaginary country of Saint Theodoros. The setting is inspired by a current conflict at the time: the Chaco War, which between 1932 and 1935 pitted Bolivia and Paraguay against one another for control of the Northern Chaco. Hergé disguised the names, turning Bolivia into San Theodoros and the seat of Government, La Paz, into Las Dopicos; Paraguay appears as Nuevo Rico, and Asunción, its capital, as Sanfación (Farr, 2002, p. 62). The album is the first in which Hergé uses imaginary countries as the setting for the action, and prominent characters from the series appear for the first time, such as General Alcázar.

In The Black Island, which began publishing in April 1937, the action moves to Scotland. At a time when pre-war tensions due to Hitler's expansionism were more than evident, Hergé signed an espionage story in which the main villain was a German, Dr. Müller. Although the first editions of the album contained numerous setting errors, they would be solved years later when the edition was made for the British market, in 1965, largely thanks to the collaboration of Bob De Moor. It is the only one of the Tintin albums of which there are three editions: the first, in black and white, appeared in 1938; a second in color, in 1943, during the German occupation; and the third and final one in 1965.[citation required]

The next album was Ottokar's Scepter. The plot of the book, in which an expansionist dictatorship (Borduria) appears that wants to annex a small neighboring monarchy (Syldavia) through intrigue, has obvious analogies with the German Anschluss of Austria (1937), and with the subsequent incorporation of Czechoslovakia into the Reich (1938). These analogies, furthermore, become even more evident when reading the name of the Bordurian dictator: Müsstler, an obvious amalgamation of the names of Benito Mussolini and Adolf Hitler. Especially since its reworking for the color edition in 1947, Ottokar's Scepter stands out for its careful setting, to which Edgar Pierre Jacobs was no stranger (in gratitude, Hergé portrayed him as a Sildavian officer on page 59 of the color edition of the album) (Farr, 2002, p. 87) Hergé endowed Syldavia, an imaginary country that would again be the scene of other Tintin adventures in the future, with all the attributes of a true state: he invented his history - which is summarized in a tourist brochure that Tintin reads on pages 19 to 21 of the album -, his folklore, the complicated ceremonial apparatus of his court, and even his language, Syldavian, which, although it sounds exotic, is nothing more than a mixture of Dutch and the Brussels dialect (Farr, 2002, p. 86). Ottokar's Scepter also stands out for the appearance of the most prominent female character (in fact, the only one of true relevance) from The Adventures of Tintin: the opera singer Bianca Castafiore.

The golden age (1940-1944)

Curiously, the peak of the series coincides with the German occupation of Belgium during World War II. It is at this time that several of the most important characters in the saga appear, including Captain Haddock (in The Crab with the Golden Claws) and Professor Tornasol (in Rackham's Treasure the Red). It is also the time when Tintin albums began to be published in color (since 1942). However, authors such as Fernando Castillo affirm that the age of maximum plenitude is the last with albums such as Las Joyas de la Castafiore, described by the writer as the best of all.

With Le Vingtième Siècle closed by order of the occupiers, Hergé agreed to collaborate in the newspaper Le Soir, controlled by the Germans. This was one of the most controversial decisions in Hergé's life, which would cause him many problems in the future.[citation required]

The circulation of Le Soir, of around 250,000 copies (Assouline 1997, p. 130), allowed an even wider dissemination of Tintin's adventures. At first, the new adventure, The Crab with the Golden Claws, appeared in the newspaper's supplement, Le Soir Jeunesse, every Thursday starting on December 17. October 1940. In September of the following year, however, due to paper restrictions, the supplement ceased publication, and the comic began to appear in the daily editions of the newspaper, in a press strip format of only three or four vignettes. This meant a significant increase in Hergé's work pace, who was forced to make about 24 vignettes a week instead of the 12 to which he was accustomed.

In an apocalyptic atmosphere, The Mysterious Star, Tintin's next adventure, stages the rivalry between Europeans and Americans to find a mysterious meteorite. The album was later highly criticized for the character of the New York Jew Blumenstein, the album's main villain, and for a vignette in which two stereotypical Jews appeared, one of whom is happy about the news of the end of the world because "< i>this way I wouldn't have to pay my suppliers". This last vignette was deleted in the album edition; As for Blumenstein, in later editions of the work Hergé changed his name to Bohlwinkel, and located him, instead of New York, in an imaginary country, São Rico. However, he later discovered, to his surprise, that Bohlwinkel was also a Jewish surname (Sadoul, 1986, p. 50).

The Mysterious Star was the first of the Tintin albums released in color, in 1942. The following year some previous albums were reissued in color: The Broken Ear, The black island and The crab with the golden claws. Another prominent comic book author, Edgar P. Jacobs, played an important role in these new versions of the albums.[citation required]

The following two books constitute one of Hergé's most ambitious works: the diptych composed of The Secret of the Unicorn and The Treasure of Rackham the Red, in which The influence of Stevenson's classic adventure novel Treasure Island is evident. It is in the second of the albums that Professor Silvestre Tornasol makes his appearance, the paradigm of the clueless and somewhat crazy scientist, whose physical features Hergé based on those of the famous Auguste Piccard. In this adventure, Tintin and Haddock set off to distant lands in search of a treasure that, paradoxically, they find in the castle that had belonged to the captain's ancestors, Moulinsart, converted from this moment on into the home of Haddock and Tornasol, and often also from Tintin himself.[citation required]

In December 1943, Le Soir began publishing another long-term adventure, The Seven Crystal Balls, in which a mysterious curse haunts the archaeologists who have discovered the tomb of the Inca Rascar Cápac. The publication of this adventure, however, was interrupted by the liberation of Belgium by the Allied troops in September of the following year.[citation required]

After liberation (1944-1950)

Brussels was liberated by the Allies on September 3, 1944, which meant the immediate interruption of the publication of Le Soir and, consequently, of The Adventures of Tintin i>. The action of The Seven Crystal Balls was interrupted at the moment when Tintin leaves the hospital where the archaeologists affected by the curse of the Inca Rascar Capac are hospitalized (page 50 of the current edition of the album). The last strips described his meeting with General Alcázar, about to travel to South America. [ citation needed ]

For Hergé, accused of collaborationism, a personal ordeal began, since he was prevented from continuing to work, and had to answer for his attitude during the occupation. This situation was put to an end by the intervention of Raymond Leblanc, a former member of the Belgian resistance, who gave Hergé the opportunity to continue his reporter's adventures in a new magazine, which would bear the name of the famous character, Tintin<. /i>, and whose first issue appeared on September 26, 1946. The new project was a success from its beginning, despite strong competition from other weeklies aimed at youth audiences: its initial circulation was about 60,000 copies, a fairly high number for the time, and after a few numbers it reached 80,000.

Hergé recovered his character from the first issue of the magazine. With some small changes (a meeting between Tintin and Haddock was interspersed), the action of The Seven Crystal Balls resumed where it had been interrupted. Instead of the single black and white strip that had been used in recent times of Le Soir, the new magazine published three color strips on the central double page (Farr, 2002, p. 121), which allowed Hergé to take more care of the setting, and introduce in some of the plates an explanatory text about the Inca civilization. The Temple of the Sun, the second part of The Seven Crystal Balls, continued to be published in the magazine Tintín until April 22, 1948. Two parts of the adventure would appear in an album, in color, in 1948 and 1949, respectively, with significant modifications (Farr, 2002, p. 123).

After the publication of this narrative diptych was completed, Hergé decided to resume, eight years later, the adventure that had been interrupted in 1940 due to the German invasion, In the land of black gold. In his resumption, the author incorporated characters and situations after the moment in which the work had begun: Haddock appears (although very briefly), whose first appearance in the Tintin series had taken place in The Crab with the Pincers of gold, started after In the Land of Black Gold, and even already resides in Moulinsart, the mansion that he had only acquired at the end of The Treasure of Rackham the Red. The action initially took place in the British Mandate of Palestine, with references to Irgun terrorism; In a later edition, made in 1971 at the request of his London publisher, Hergé moved the setting of the album to an imaginary Arab country (the Khemed), without concrete historical references (Farr, 2002, p. 129). They appear on this album. for the first time two important figures: the Emir Mohammed Ben Kalish Ezab and his son, Prince Abdallah.

The fifties

In 1950 the Hergé Studios were created. The author, who had until now faced the responsibility of making the character's albums alone (with the exception of his period of collaboration with Edgar Pierre Jacobs), now had a whole team of assistants at the service of he. Among them, the work of Bob de Moor deserves to be highlighted. The first work of the Hergé Studies was a new narrative diptych in which for the first time his character made an incursion into the field of science fiction, the one constituted by the albums Objetivo: la Luna and Landing on the Moon, which were published in the magazine Tintin between March 30, 1950 and December 30, 1953. The publication was interrupted for 18 months, between 1950 and 1951, due to Hergé's exhaustion (Farr, 2002, p. 141).

Hergé worked intensely on the documentation of the new project, to the point that, in 1969, more than fifteen years after the conclusion of the publication of Tintin's lunar adventure, Apollo XI actually landed on the surface of the Moon, the comic was quite close to reality (Farr, 2002, p. 135). In fiction, the promoters of the trip are the rulers of the small fictional country of Syldavia, which had already appeared in The Scepter of Ottokar; In an isolated place, they gather numerous scientists, under the direction of Professor Tornasol, and build a rocket powered by atomic energy, whose design is inspired by that of Wernher von Braun's V-2. Tintin will board, along with Snowy, Haddock, Tornasol and—involuntary stowaways—Hernández and Fernández. The success of Tintin's lunar trip was such that, after Neil Armstrong stepped on the surface of the Moon, the magazine Paris Match commissioned Hergé to make a short comic-report narrating the next space mission., that of Apollo XII.

In December 1954, the publication of Tintin's next adventure began, The Tornasol Affair, a spy story, set against the backdrop of the Cold War, whose action takes place in Borduria., a country whose dictatorial regime has great similarities with those of the communist countries of Eastern Europe (its ideology, mustache, is powerfully reminiscent of Stalin's personality cult in the Soviet Union). In the album they appeared for the first time two of the most remembered secondary characters of the series: Serafín Latón, "characteristic type of the self-satisfied Brusselsian" (Sadoul, 1986, p. 109) and the evil Colonel Sponsz. In order to obtain documentation for the making of the album, Hergé undertook a trip to Switzerland, since part of the plot also takes place in Geneva.

The next adventure was Coke Stock, an album in which Hergé returns to the Arab world, which he had already visited in previous installments of the series (Pharaoh's Cigars and In the country of black gold). The album is a denunciation of slavery: Tintin must on this occasion fight against a network of arms and slave traffickers, which affects African Muslims on a pilgrimage to Mecca. Coke Stock received criticism for the stereotypical language of Africans, and Hergé was branded racist, so in 1967 he published a new, corrected edition of the album, in which he modified the way of expressing himself. the victims of the slave trade (Farr, 2002, p. 152-153).

When Coke Stock ended, Hergé was immersed in a deep personal crisis. His marriage to Germaine Kickens had broken down because of his relationship with his future wife, Fanny Vlaminck, a young woman who worked at the Hergé Studios and who was twice his age. Hergé's response to this crisis was the writing of one of his best-known albums, Tintin in Tibet, which the author himself considered 'a hymn to friendship';. In this album Tchang, Tintin's companion in The Blue Lotus , reappears, and the protagonist risks his life to save him. The comic also reflects the situation in Tibet, which had been invaded by China in 1949; Furthermore, just nine months before the comic's publication concluded, the Dalai Lama had gone into exile in India fleeing Chinese repression. Hergé clearly takes sides with the Tibetans. The mythical Yeti also appears on the album, about which the author of Tintin had read extensively.[citation required]

The 1950s marked the beginning of the series' international success. In 1956, Tintin albums sold one million copies a year for the first time (Sadoul, 1986, p. 17), and translations into several foreign languages began (see the section Translation into other languages).

The latest Tintin albums

The last adventures of Tintin were published very spaced apart: between The Castafiore Jewels (1961-1962) and Flight 714 to Sydney (1966-1967) four years passed; Between the latter and Tintin and the 'Pícaros'' (1975-1976), the last one published by Hergé, eight passed.

The Jewels of Castafiore has attracted attention because it deviates from the usual structure in the character's albums: for the first time there is no trip (the action takes place exclusively in the castle of Moulinsart, Haddock's residence), nor a true mystery. In the author's words:

[...] I had the malicious pleasure of confusing the reader, of keeping him in the unknown, depriving me of the traditional panoply of the «comics»: there is no «bad», there is no real suspense and there is no adventure in the very sense of the term (Sadoul, 1986, p. 115).

The album is a kind of comedy with a police plot, which has evoked for some the tone of certain novels by Agatha Christie (Farr, 2002, p. 171), or some Hitchcock films. It is worth highlighting the sympathy with which Hergé portrays the gypsies in the album (Farr, 2002, p. 175).

After the publication of The Castafiore Jewels, Hergé tried to dedicate himself mainly to painting, abandoning the series (Farr, 2002, p. 179). He became a prominent art collector (the art world will be very present in his latest albums, especially in the last one, Tintin and the Alpha-Art). Precisely in those years (the first half of the 1960s), Tintin's most serious competitor in the field of Franco-Belgian comics, Asterix, began his journey. [citation needed]

According to Assouline (1997, p. 316) it was partly due to the dazzling success of Asterix that Hergé decided to recover Tintin, starting in 1966 the publication of a new adventure of the character, Flight 714 to Sydney. The new album, for which the series creator delegated much of the work to his team, was considered inferior to his previous works (Farr, 2002, p. 183). The plot, which includes science fiction elements such as the presence of extraterrestrial beings, is however enriched by the presence of new characters, such as Laszlo Carreidas or Mik Ezdanitoff, in addition to making the quintessential villain of the series, Rastapopoulos, reappear.

Until the publication of the next adventure, the last one published, eight years passed, during which the author was busy with tasks such as the reform of The Black Island for its edition in the United Kingdom, or the production of animated films based on his character (Farr, 2002, p. 190). Tintin and the 'Pícaros'' began to be published in 1975. Inspired by the affair of Régis Debray and the Tupamaros (although there are also echoes of the Revolution in the story Cubana), Hergé returned Tintin to the South American republic of San Theodoros, where he reunites with old acquaintances, such as General Alcázar, Colonel Sponsz, General Tapioca, and the explorer Ridgewell, from The Broken Ear. i>. New characters also make their appearance, such as Peggy, General Alcázar's wife, who is the daughter of another character in the series, Basil Bazaroff (The Broken Ear) (Farr, 2002, p. 190). This album offers a modernized image of Tintin, who has discarded his usual baggy pants for bell-bottom jeans, wears a pacifist symbol on his helmet, and practices yoga.

Tintin and the Rogues was the last of the Tintin adventures published by Hergé, who died in Brussels on March 3, 1983.[citation required ]

Tintin and Alpha Art

When he died, Hergé left unfinished a new album that he was working on, which, among other topics, talked about modern art and religious sects. The existing material consisted of only three pencil-drawn plates, forty-two sketches, and some additional writings with part of the script for the new adventure, which however remained unfinished. The possibility of having a collaborator of the creator of Tintin finish the album was considered, and special thought was given to Bob de Moor, who had played a fundamental role in the preparation of other books in the series. It was also suggested that it be turned into a posthumous tribute to the creator of Tintin, with the participation of numerous cartoonists. However, in 1986 Hergé's heir, his widow Fanny, finally decided that the album be published in the state in which the author had left it, with the title Tintin and the Alpha-Art. [citation required]

The rights to the character and his adventures belong to the Hergé Foundation, a company managed by the cartoonist's widow, Fanny Vlamnick (repository of the copyright and universal heir of Hergé) and her second husband, the British Nick Rodwell. Although his management has not been without criticism, due to his tight control over all types of tributes and derived fanart, the decision not to continue the character's adventures has been maintained to date.

Analysis

Creating an album

Making a Tintin album involved a fairly complex process. Hergé (Sadoul, 1986, p. 39 and 45) describes it in the following way: after writing a synopsis of two or three pages, he proceeded to plan the plates, sketching sketches and always trying to maintain an element of suspense at the end of each one. they. Later, on large-format plates, he made drafts of the pages, which he finally traced to obtain the final version. The dialogues and settings were then inserted onto the page; Finally, it was converted to ink and sent to the printer. After the printing test, the plate was colored. After the creation of the Hergé Studios, in 1950, the final phase of the creation of the plates (especially the decorations) was frequently carried out by their team. of collaborators and not by Hergé in person. Likewise, the author sometimes delegated documentation work to his subordinates: Bob de Moor, for example, traveled to Scotland in 1958 to give greater credibility to a new edition of The Black Island intended for the British market.

In the first stories, Hergé did not have any type of limitation regarding the length of the albums, and he adapted it to the needs of the story he was telling. Thus, Tintin in the Land of the Soviets has 130 pages; the first version of The Crab with the Golden Claws, on the other hand, has 104. During the German occupation of Belgium, coinciding with the introduction of color in the series and due to the increase in the price of paper During the war, the author was forced to limit the number of pages in each album to 62. The first book to be published with this number of pages was The Mysterious Star, in 1942. From that moment on, all Tintin albums (and the color versions of the previous adventures) respected that format, although some adventures are told in two albums instead of one.[citation needed]

Hergé's style: the clear line

The Tintin albums, like the rest of Hergé's work, have a characteristic graphic style, known since 1973 as "clear line", a hallmark of the so-called "Brussels School", in contrast to the "Brussels School". de Marcinelle", to which other great authors of Belgian comics belonged, such as Jijé or Franquin. Hergé's style, which has its remote origin in the work of American authors of the early 20th century, such as George McManus, It reaches its full potential especially from the 1940s onwards, with the introduction of color.

The "light line" is characterized by discarding the effects of light and shadow, textures and color gradations in favor of flat colors, without nuances. The line, which is not intended to be expressive, is of identical thickness in all the elements of the drawing (characters, decorations, etc.). The vignettes, almost always rectangular, have a regular distribution on the page. The movements of the characters are always from left to right, in the sense of the reading:

When drawing a character running, he usually goes from left to right, by virtue of this simple rule; and furthermore, this corresponds to a custom of the eye, which follows the movement and accentuates it; from left to right the speed seems greater than not from right to left (Sadoul, 1986, p. 56).

The characters are halfway between realistic and cartoonish. A characteristic feature is the meticulousness with which the scenarios are drawn, full of details. This entails important documentation work, which in The Adventures of Tintin became essential, especially after The Blue Lotus. Comparing Hergé's vignettes with the photographs he used for documentation, the meticulous fidelity of his drawings is verified. A certain "obsession with the object" has been described in The Adventures of Tintin, which leads Hergé to draw with meticulous precision all kinds of things, which shape what he himself author called the "imaginary Tintin museum". Some of these objects have become true icons of the 20th century, such as the white and red checkered moon rocket from Landing on the Moon.

For Hergé, the clear line was not simply a matter of aesthetics. His refined graphics are always at the service of the narrative: in fact, the main objective of visual clarity is to facilitate the reader's understanding of the story.

The adventure

The first stories lacked a solidly constructed script. They limited themselves to narrating a succession of gags and adventures. As they were published in installments, it was important to always maintain the suspense at the end of each issue:

Exactly, up there [The Blue Lotus], the adventures of Tintin (like those of Totor) formed a series of gags and suspenseBut there was nothing built, there was nothing premeditated. I myself went out to adventure, without any script, without any plan: it was, really, a weekly job. I didn't just consider it a real job, but a game, a joke... Hey, Le Petit Vingtième I went out on Wednesday afternoon and many times it had occurred to me that on Wednesday morning I still did not know how to get out of the coil in which I had put Tintin in the previous week (Sadoul, 1986, p. 36).

After El Loto Azul, however, the albums have a much more defined narrative structure (although without giving up the gags, and maintaining the element of suspense at the same time). end of each delivery). This narrative structure, coinciding with that of classic adventure novels, is mainly provided by the outline of the trip. There are trips in all the albums, except two (The Jewels of Castafiore and the unfinished Tintin and the Alpha-Art). In books from what can be considered the classic period of the series (those written immediately before and during World War II), the trigger for the adventure is often the chance discovery of an object, symbol of a mystery that the protagonist must solve. A paradigmatic example are the three scrolls of The Secret of the Unicorn, which reach the protagonist thanks to a series of coincidences. Other times it is the loss of an object that needs to be recovered (the stolen Arumbaya fetish in The Broken Ear, for example). In almost all the adventures of the series an object appears that has an essential role in the plot (and that sometimes gives name to the albums, as happens in Ottokar's Scepter). In one of his most atypical works, the author makes fun, in a way, of this very common device of his: in The Castafiore Jewels, the disappearance of the jewels is not a true mystery.< sup>[citation required]

In his first adventures, Tintin travels alone, accompanied only by Snowy, although he has eventual travel companions. The first truly collective adventure is The Mysterious Star, in which the reporter is part of a scientific expedition that sets out in search of a meteorite. Since The Secret of the Unicorn, it has become common for what could be considered the "family" closest to Tintin: Haddock, Hernández y Fernández and Professor Tornasol. The interactions between these characters, often of a comic nature, considerably enrich the narrative.[citation required]

The importance of the trip links the series with classic works of youth literature, such as those of Jules Verne (whom, despite the obvious coincidences, especially in Tintin's lunar adventure, Hergé claimed he had not read) and Robert Louis Stevenson (the influence of Treasure Island on the pirate story of The Secret of the Unicorn and Red Rackham's Treasure is obvious >).

The plots of some albums have elements typical of detective novels (in relation to the plot of The Castafiore Jewels Agatha Christie and Alfred Hitchcock have been cited). The visual gags are reminiscent of the slapstick humor of silent comic films; in fact, in the appearance of some characters (especially Hernández and Fernández), there are certain echoes of great actors from this time, like Charles Chaplin.[citation needed]

The world of Tintin

During his adventures, Tintin travels around the globe (and even goes outside of it, to visit the Moon). Travel through North America (Tintin in America) and South America (The Broken Ear, The Temple of the Sun, Tintin and the Rogues), Europe (Tintin in the Land of the Soviets, The Black Island, Ottokar's Scepter, The Calm Affair), Africa (Tintin in the Congo, The Crab with the Golden Claws), Asia (The Blue Lotus, Coke Stock, Tintin in Tibet) and Oceania (Flight 714 to Sydney). He visits the most varied landscapes, from the Arctic (The Mysterious Star) to the Sahara Desert (The Crab with the Golden Claws). To the point that authors like Castillo affirm that within his work there is a poetics of travel.

Sometimes Tintin's adventures take place in real countries (including China, the Belgian Congo, the United States, Egypt, India, Peru, the United Kingdom, Switzerland, Tibet, and the Soviet Union); other times they take place in fictional countries created by Hergé for the series, such as the South American republic of San Theodoros or its neighbor New Rico, the small Balkan monarchy of Syldavia, its enemy Borduria, or the emirate of Khemed, on the shores of the Red Sea. Setting Tintin's adventures in these imaginary countries allowed Hergé to deal with current political issues without fear of problems like those he had when he dealt with the Japanese invasion of China in The Blue Lotus. In fact, the stories often address current issues, to the point that the story of Tintin can be said to be the story of the century XX: the Chaco War (in The Broken Ear), Nazi expansionism (in Ottokar's Scepter), the Cold War (in The Tornasol Affair), the South American guerrillas (Tintin and the Pícaros).[citation required]

Tintin, an unrepentant traveler, however, does not have a true home. Since his first adventures, he lives in one or several extremely impersonal apartments.[citation required] The address of at least one is known: Calle del Labrador 26. There is only one reference to the city in which it is located: in Tintin in Tibet, Tchang's letter has the address written in Chinese characters: « Hong-Kong, Tchang-Tchong Jen - for Mr. Tintin - Belgium Brussels »[citation required]

The closest thing to a real home in the series is Moulinsart Castle, the plot of Haddock's ancestors acquired by him, with the help of Tornasol, at the end of the album Red Rackham's Treasure. Although the only permanent resident of the castle is Haddock (always accompanied by his faithful butler Nestor), Tintin, Tornasol and even Bianca Castafiore spend long periods of time there. [citation needed]

Absences

A striking characteristic of the series is the almost complete absence of female characters. The only important one, the singer Bianca Castafiore, is above all a comic character. None of the other women who appear in the series have any real relevance.[citation needed]

Other authors, on the contrary, find other absences of both conflicts and international events more striking. Hergé dwells a lot on some that were or were at that time very little relevant, while he leaves out several of global importance. Thus he uses as a backdrop the aforementioned Chaco War, a conflict between two not very significant South American countries. He also shows the beginnings of the Arab-Israeli Conflict in Tintin in the Land of Black Gold, a very big problem decades later, but one that raised few concerns at the time. He even alludes to the Micronesia Conflict, changing the name to "Sondonesia" on the album Flight 714 to Sydney (Farr, 2011), a very minor war then and now. However, other international issues that aroused a flood of solidarity or interest in their time and later do not appear, such as the Russo-Finnish War, the Italian Invasion of Abyssinia, the Turkey of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk and especially the Second World War that did not even appear. is mentioned.

Taking into account that Tintin is a journalist drawn and scripted by another journalist, absences commented on by authentic reporters are surprising. Thus, in Tintin in the Congo we see how different representatives try to negotiate a contract with him, but the concern of every special envoy to compile the expense invoices is never shown. He handles money, even in amounts that allow him to purchase boats and rent aircraft with pilots, but he never appears changing currency, as if the Belgian franc were quickly convertible. Nor is there a single vignette where he is shown writing a news story or chronicle, nor worrying about reaching the telephone, telegraph or any other means that allows him to transmit it to his editorial office on time.

Finally, in the emotional/personal sphere, it is worth noting the total absence of mentions of his childhood, or his classmates at school, university, work... There is no reference to parents, siblings or any member of his family close or extensive. The only people with whom he has emotional relationships are the ones he meets during the course of his adventures. Many of these relationships are established for a short time, despite this, they are very long-lasting and deep, such as the one with Tchang, for whom he even risks his life in Tintin in Tibet, or the Portuguese merchant Oliveira da Figueira, who hides them inside his house in Coke Stock and sacrifices all the jugs so that Tintin and Haddock can master carrying them in the Arab style (Farr, 2011).

Ideology

Much has been written about the ideology of the series The Adventures of Tintin. The work has been the subject of controversy, largely due to the continuous reissue of works that were conceived many years ago and in an entirely different context. Hergé has been accused of espousing colonialist, racist and even fascist views in his albums; He has been criticized for his alleged misogyny, given that women hardly appear in the series; and he has been accused of showing unnecessary cruelty to animals in an album (Tintin in the Congo). These accusations refer to specific aspects of some specific albums, but it cannot be said to be the predominant point of view in the series. In this sense, there is a certain "black legend" of Tintin, which was undoubtedly contributed by the fact that Hergé collaborated during the German occupation of Belgium in a newspaper controlled by the Nazis.

Tintin in the Congo is the album in which colonialist and racist ideology is most present. In it, the indigenous Africans are shown as indolent and stupid, and Tintin adopts a paternalistic attitude towards them. Hergé did not deny that colonialism was present in the album; It was, as he stated, the norm at the time:

I made this story, I have already told you, according to the optics of the time, that is, with a typically paternalistic spirit... that was, and I affirm it, the spirit of all Belgium (Sadoul, 1986, p. 97).

Another album that was criticized as racist is much later: it is Coke Stock. Although the adventure is a denunciation of slavery in which Tintin and Haddock clearly take sides with the weakest, an article published in 1962 in the magazine Jeune Afrique harshly criticized its representation of Africans (Sadoul, 1986, p. 97), especially in terms of his way of speaking. Hergé accused the criticism, and for a new edition of the album, published in 1967, some dialogues were rewritten.

The idea of fascism in Tintin may be related to the author's attitude during the war, as well as his initial connection with the Abbe Norbert Wallez, a man of the extreme right and declared anti-communist. The albums that Hergé published during the war, however, are adventure stories in which there are no allusions to politics, in one sense or another. Critics of the series, carefully scrutinizing the albums, have found a tenuous propaganda intention in The Mysterious Star, in whose first version a European expedition competes with another American one, financed by a New Yorker with a Jewish surname who is the main villain of the album.[citation needed]

Other albums, however, deny Hergé's supposed sympathy for fascism. Before the war, in Ottokar's Scepter, there are obvious criticisms of Hitler's expansionist policy (according to the author, it is the story "of a failed Anschluss). #34;) (Sadoul, 1986, p. 71). Hergé spoke out against all totalitarianisms, whatever their form:

Look, I think all totalitarianisms are bad, whether they are "right" or "left" and I put them all in the same sack (Sadoul, 1986, p. 71).

He never denied, however, his conservative ideas. Perhaps for this reason, Tintin is generally in favor of the established order, which does not prevent him from paying attention to the most disadvantaged, and, on many occasions, taking energetic sides with them: the Indians in Tintin in America, the Chinese who suffer Japanese oppression in The Blue Lotus, or even the African slaves in Coke Stock. Throughout his travels, Tintin generally shows a genuine interest and respect for non-European cultures, which is also manifested in Hergé's willingness to thoroughly document himself for the making of the albums.

Esotericism

One of the most curious features of Tintin's albums is the relatively frequent presence in them of elements from the Beyond and the so-called Occult Sciences. We list them here:

- Angels and demons. In The broken earThe two main antagonists of the album die drowned, and it shows some demons taking them to hell. On the other hand, in several albums we see that both Milú and Captain Haddock sometimes hold mental conversations with an angel and a demon bearing their heads; they are often seen in situations where the possibility of surrendering to a particular pleasure comes into conflict with a mission or a duty, and the results are very diverse. In these vineyards, the presence of the spiritual world acquires a distinctly comical pattern.

- In the double album The cigarettes of the Pharaoh and The blue lotus, appear an evil faquir and another good, and both show various extraordinary powers.

- Professor Tornasol, from the moment you know him in the double album. The Secret of the Unicorn and The Treasure of Rackham the Red, it is very competent in the pseudoscience of radioesthesia, and maintains this hobby throughout the rest of the collection, although in several albums never use it. Detectives Hernandez and Fernandez also use this method in The Temple of the SunTo try to find Tintin and his friends. In all cases it is shown that the indications given by the pendulum are accurate, but without identifying specific places.

- Magic is one of the main argumental elements of the double album The seven crystal balls and The Temple of the Sun. There you can see how a Peruvian Indian throws a crystal ball at each of the seven archaeologists who participated in an expedition that found and brought to Europe the mummy of the Inca King Rascar Capac; these balls raise them in a deep narcotic dream, and an Inca priest tortures them, from the enormous distance, and always at the same hour of the day. Before this, at the beginning of the story, during a show of the Music-Hall attended by Tintin and the captain, a seer named Yamilah shows the public some extraordinary gifts of divination; but he is frightened, until he shouts and faints, when a woman of the public foresees the coming of a terrible inca curse upon her husband, which turns out to be one of the expeditionaries.

- The whole plot of Tintin in Tibet part of a premonitory dream that Tintin has, where he sees his friend Tchang alive after an aviation accident where apparently there have been no survivors. Tintin is so absolutely convinced of the reality of his dream, that he risks everything to go to the Himalayas and rescue Tchang, facing the opposition of almost everyone. In this album we can also see a Tibetan monk (Blessed Ray) levitate and have prophetic visions, which are always fulfilled. And besides, one of his most significant characters is the legendary Yeti.

- In The jewels of the CastafioreAn old gypsy reads his hand to the captain, and advances all the events that will happen in history.

- The whole plot of Flight 714 to Sydney It happens on a volcanic island of the Pacific, and it is solved with the appearance of an ovni and alien beings, whose appearance we never see. In addition, it is shown how an unknown ancient local culture had built an underground temple, where it represented beings of space; it is thus understood that on that island the visits of alien beings were frequent. At the end of the story, Tornasol shows on television an artificial object that he had found using radioesthesia; and he has no empacho to declare that, because of his anomalous chemical composition, it could only be an object of alien origin.

Tintin's rivals

During its first ten years of history, no other character in the Belgian comics overshadowed Tintin. In 1938, however, the magazine Spirou was created, in which the adventures of a new paper hero, Spirou, who would become Tintin's main competitor for decades, would develop. The characters were the banners of two antinomian tendencies in the world of Belgian comics: the so-called "Brussels School" (Hergé) and the "Marcinelle School" (whose main representative was André Franquin). Hergé deeply admired the virtuosity of Franquin's drawing, even though his aesthetic was the opposite of that of The Adventures of Tintin.

Tintin had, however, other competitors who did not come from the outskirts of Brussels, but from the United States: in 1949 the magazine Mickey's Journal began to be published in Belgium, with comics of the Walt Disney's most iconic characters, a serious rival for Tintin magazine in the post-World War II period.

The most successful of Tintin's rivals would, however, arrive at the end of the 1950s: on October 29, 1959, the first installment of the warrior's adventures was published in the French magazine Pilote Gaul, Asterix. The popularity of the new character meant that in the mid-60s, sales of his albums reached those of the Tintin books. Currently, sales of Asterix albums are higher. Despite everything, according to a survey, in 2005 Tintin was the comic character most valued by the French, slightly ahead of Asterix.

The other authors of Tintin

Hergé developed his first albums completely alone. However, starting in the 1940s, his workload required him to hire collaborators. They were never credited on the albums, but they played an important role in the series' history.

Edgar Pierre Jacobs

Hergé's first important collaborator on The Adventures of Tintin was Edgar P. Jacobs (1904-1987). Jacobs collaborated closely with Hergé between 1944 and 1947. His main work consisted of correcting, reformatting and coloring several black and white albums (Tintin in the Congo, Tintin in America, The Blue Lotus and Ottokar's Scepter), which were reissued in color in the 1940s. In addition, he participated in the decorations of the albums The Treasure of Red Rackham, The Seven Crystal Balls and The Temple of the Sun). Jacobs stopped collaborating with Hergé in 1947 to develop his own series, Blake and Mortimer.

Although he is not credited on the albums in which he collaborated, he is portrayed in some of the albums in which he participated. He appears alongside Hergé himself (and alongside Quique and Flupi) in the opening vignette of Tintin in the Congo. He also appears on the cover and in an interior panel of the color edition of The Pharaoh's Cigars , in a somewhat macabre joke: a sarcophagus with the sign E.P. Jacobini. In Ottokar's Scepter , he attends, together with Hergé himself, a Castafiore concert and a royal reception (pages 38 and 59 of the album).

Bob de Moor

Bob de Moor (1925-1992) worked at Hergé Studios from its creation in 1950 until his death. He played a decisive role in several albums, such as a new edition of The Black Island (1965), Objetivo: la Luna (1953), Aterrizaje en la Luna (1954), Flight 714 to Sydney and Tintin and the Rogues (1976). The review of The Black Island was done primarily thinking about its release for the British market, since numerous inaccuracies had been detected in the Scottish setting of the album, and De Moor traveled to the United Kingdom to carry out meticulous documentation work. In the diptych about the trip to the Moon, the design of the famous rocket and the lunar landscapes are due to his hand (Farr, 2002, p. 141).

He also participated in the production of the cartoon versions of The Temple of the Sun and Tintin and the Lake of Sharks. His mark is evident in works such as Tintin and the Rogues , in which he took charge of most of the graphic work. For a time, the possibility of finishing the album that Hergé left incomplete upon his death, Tintin and the Alpha Art, was considered. However, he is never credited on any of the Tintin albums.

Jacques Martin

Jacques Martin, who was a contributor to the magazine Tintín, entered the Hergé Studios in 1953. He worked on the scripts for albums such as The Tornasol Affair , Coke Stock , The Castafiore Jewels and Tintin in Tibet . He also drew the characters' dresses in these same albums. In an interview, Martin is credited with the main idea of some albums. His collaboration with Hergé lasted until 1972, the year in which he dedicated himself exclusively to his own series: Lefranc and, above all, Alix.

Characters

Tintin

Tintin is a young Belgian reporter who often gets into trouble for defending just causes. His physical appearance and his wardrobe hardly change over the years. Of short stature, he is blonde and sports a characteristic pompadour, his main hallmark, along with the baggy pants that he will wear in all his albums (with the exception of the last one, Tintin and the Rogues, where he wears pants Cowboys). From his first adventure, he presents himself as a journalist: he travels to the Soviet Union and then to the Congo as a reporter for Le Petit Vingtième, although only in Tintin in the Land of the Soviets is introduced writing a report. Starting with the third album of the series, there are no longer references to the diary in which Tintin collaborates, although the character does not stop presenting himself as a reporter, and sometimes uses his profession as a means of making inquiries about his adventures.

In the albums no indications are ever given about Tintin's age, nor about his family, emotional or sexual circumstances, standing out for his unwavering honesty, to which Hergé's admiration for the scout movement is not unrelated. In the same way,

He also lacked a sense of humor, although he moved into stories where humor played an important role. If at first it ran from the villains, as pathetic as bad, characters such as Hernández and Fernández, Captain Haddock or prof soon appeared. Tornasol, rounding up a cast that has made immortal and unforgettable the adventures of the character.

Snowy

Since his first adventure, Tintin is accompanied by his pet, Snowy, a white fox terrier, therefore being the only character, apart from the protagonist, who appears in all the adventures of the series.

Snowy is not able to speak, but her thoughts are often verbalized in speech bubbles. He is usually able to make himself understood. His love for bones and his more human than canine interest in whiskey (especially the Loch Lomond brand, Captain Haddock's favorite) often trigger comic situations.

Captain Haddock

Captain Archibaldo Haddock is a merchant navy captain whose nationality is not clarified in the albums (English, French or Belgian?), although it is known that he has a French ancestor (the Chevalier de Hadoque, a sailor in the service of Louis XIV). The surname Haddock comes from a conversation that Hergé had with his wife, in which she commented that the haddock (a type of smoked haddock) was a 'sad English fish';. The captain's first name, Archibald, is not revealed until Tintin's final adventure, Tintin and the Rogues (1976).

Archetype of the sea lion, its appearance fits perfectly with this model: cap, blue sweater with the drawing of an anchor, bushy black beard. Rude and kind-hearted, although irascible, he is Tintin's inseparable companion since he made an appearance in The Crab with the Golden Claws, where he is presented as a weak and dominated by his alcoholism. Later he becomes a more sympathetic character, even without abandoning his weakness for whiskey, in which he has a special predilection for the Loch Lomond brand (his drinking binges of it are often used as comic gags). His short temper, his thoughtless impulsiveness, and his wide repertoire of outlandish insults are commonplace in the series, and help provide a counterpoint to the generally calm and level-headed Tintin.

After the apparently fruitless search for Red Rackham's treasure, Professor Tornasol helps him acquire his family's castle, in Moulinsart, and subsequently become a peaceful rentier. This does not mean, however, that he stops accompanying Tintin on his adventures, and appears in all the albums from his appearance until the end of the series.

Hernández and Fernández

Hernández and Fernández (Dupond et Dupont in the original version) are a couple of almost identical police officers (moustache, bowler hat and cane are their three main identifying marks). They are only distinguished by their mustache, where Hernández's (Dupont) has the appearance of a turned D while Fernández's (Dupond) wears it with two small guides or "rabitos", which give it a T shape. inverted. Despite appearances, there is no family relationship between them. It has been said that Hergé could have been inspired by a photograph that appeared in the Parisian magazine Le Miroir, in which two detectives with a mustache and bowler hats appear escorting a detainee (Farr, 2002, p. 41), but the author never confirmed this information.

Dupond and Dupont, or Hernández and Fernández, made their first leading appearance in the series in Los cigarros del pharaón, in 1934, with the names of X 33 and X 33 bis. Later Hergé had them appear in the color edition of a chronologically earlier album, Tintin in the Congo, in whose crowded first vignette they can be seen, somewhat separated from the main group that says goodbye to the reporter. They appear on all subsequent albums in the series, with only two exceptions (Tintin in Tibet and Flight 714 to Sydney) (Farr, 2002, p. 41).

Although in the first album in which they appear (Los cigarros del pharaoh) they demonstrate great competence and skill as police officers, from the following album (El loto azul) they begin now to show the traits that will identify them throughout the rest of the series: their naivety and their constant blunders. Thus, for example, they stand out for their love of dressing up, but the costumes they choose always achieve the opposite effect to what they intend: instead of camouflaging themselves, they attract a lot of attention and cause hilarity among people.

Professor Tornasol

Professor Silvestre Tornasol or Arsenio Tornasol (Tryphon Tournesol in the original version) embodies the archetype of the clueless scientist. His deafness causes him to isolate himself in his own world, without knowing what is happening around him, which leads to endless comic situations.

Litmus made his first appearance in the series on page 5 of the album The Treasure of Red Rackham, in 1943, and became one of the most emblematic characters of the series, appearing in almost all subsequent albums. For its creation, it is possible that Hergé was inspired by the traits of the Swiss Auguste Piccard, inventor of the bathyscaphe (Farr, 2002, p. 106-107). Precedents can be found in other characters in the series, such as the eccentric Egyptologist Filemón Ciclón from The Pharaoh's Cigars or Néstor Halambique from Ottokar's Scepter.

His inventions oscillate between the absurd (the machine for brushing clothes or the bed-wardrobe) and the brilliant (the submarine in Red Rackham's Treasure; the ultrasound generator in The Tornasol affair; and, above all, the lunar rocket from Objective: the Moon).

Its scope of scientific interest is so broad that it is hardly credible. In Target: the Moon he is presented as an eminent nuclear physicist. In Moon Landing he is able to hear perfectly thanks to a hearing aid, and demonstrates enormous humanity and common sense. In The Tornasol Affair his invention, capable of reducing objects to dust and rubble, is coveted by great powers to turn it into a weapon of war. In The Castafiore Jewels he invents a color television that doesn't work well; and although his deafness isolates him from the entire plot of the album, a surreal conversation of his with a journalist provokes spectacular false news that will fall heavily on the captain.

One of his passions is growing roses: he even creates a new variety that he gallantly dedicates to his platonic love, Bianca Castafiore.

Bianca Castafiore

The Italian opera singer Bianca Castafiore is the only female character of any importance in the almost exclusively male world of The Adventures of Tintin. Known as "the Milanese Nightingale", Castafiore is a diva known throughout the world, and yet her voice is the object of the most intense animosity on the part of almost all the characters in the series. (with the exception of the "hard of hearing" Tornasol, who is also revealed in The Jewels of Castafiore as her shy lover). She is especially detested by Captain Haddock, with whom she forms a unique comedy duo that has her most notable performance on the aforementioned album.

La Castafiore made her first appearance in the series in Ottokar's Scepter in 1938. In total, she appears in eight of the albums in the series, including the last one, Tintin and the Art-Alpha. Despite her not being present, the characters hear her singing on the radio in at least two others (Target: the Moon and Tintin in the Tibet).

In the development of some aspects of the character, Edgar Pierre Jacobs, Hergé's collaborator since 1940, undoubtedly played an important role. Jacobs had been a professional baritone and was a great opera fan throughout his life. Hergé, on the other hand, hated this musical genre, since, according to his own words, he saw "the fat woman behind the singer"; (Sadoul, 1986, p. 33).

Although it is to be assumed that an artist of such celebrity has a wide repertoire (there are also references to her interpretations of works by Puccini and Rossini), in the series she appears linked almost exclusively to a single piece, the "Aria of the jewels” from Gounod's Faust, whose lyrics ("I laugh at seeing myself so beautiful in this mirror") are very appropriate for his enormous vanity. As she befits a diva, she is in the center of attention of the press, which attributes to her unlikely romances (for example, with Captain Haddock, in The Castafiore Jewels). Her sumptuous wardrobe (she wears models inspired by creations by, among others, Christian Dior and Coco Chanel) reflects the changing fashion of the 20th century. Bianca Castafiore always travels with her secretary, Irma, and her pianist, Igor Wagner.

Other characters

In addition to those mentioned, one of the great strengths of the adventures of Tintin is that it has the presence of a good number of interesting secondary characters, some of whom appear in several of its albums. This is the case of the evil millionaire Rastapopoulos, the main antagonist of Tintin; of the mercenary Allan Thompson; of the morally complex General Alcázar and his eternal rival in the government of the imaginary country of San Theodoros, General Tapioca (who is mentioned in several albums, but is only present in the last one); of Moulinsart's faithful butler, Néstor; of the quirky Portuguese merchant Oliveira da Figueira, and the unbearable neighbor and insurance agent Serafín Latón. Furthermore, there is a whole string of minor characters who appear in one album and repeat their presence in another: like the aforementioned Irma and Wagner, the good emir Ben Kalish Ezab of the Khemed and his son, the capricious, spoiled and hooligan prince Abdallah, the faithful Chinese friend Tchang, Pablo, or the pilot Pst; and villains like Müller, the Bordurian Colonel Sponsz, the Sildavian Colonel Jorgen, or the corrupt Commissioner Dawson. It's also worth mentioning that there is a wealth of memorable characters that make their appearance in a single album, or in double album adventures.

Sometimes, Hergé parodied real people with his characters, whose names he only slightly disguised. This is the case of the arms dealer who appears in The Broken Ear, Basil Bazaroff, whose name barely conceals the reference to Basil Zaharoff. Ezdanitoff, who appears in Flight 714 to Sydney, is inspired by Jacques Bergier, the author of the widespread esoteric book The Return of the Sorcerers, and the smuggler of The Pharaoh's Cigars is a transcript of Henry de Monfreid Less frequent is the appearance in the Tintin albums of real characters with their real names: there is only one case, that of the gangster Al Capone, who has a relevant role in Tintin in the Congo and < i>Tintin in America (Sadoul, 1986, p. 97). Others are inspired by real people with their names completely changed, such as the aeronautical industry millionaire Laszlo Carreidas, inspired by the French millionaire Marcel Dassault, the Bordurian dictator from Ottokar's Scepter Müsstler, his name says which is inspired by the two greatest dictators of the XX century, Mussolini and Hitler (Muss- for Mussolini and -tler for Hitler), the bandit Rastapopoulos is inspired by the also Greek Aristotle Onassis, and this last royal millionaire confronts Carreidas on Flight 714 to Sydney for some paintings. Captain Haddock, in one of his insults to General Tapioca in Tintin and the Rogues, scolds him Carnival Mussolini , inspired by Mussolini again, the famous Italian dictator. (Farr, 2011).

Cameos

In some albums, the author portrays himself: specifically, in Tintin in the Congo (first vignette); in The Scepter of Ottokar (pages 38 and 59); and in The Tornasol Affair (page 13). His collaborator Edgar Pierre Jacobs appears in the same vignettes of the same albums, and also in Los cigarros del pharaoh (pages 8 and 9); and in The seven crystal balls (page 16). Another of Hergé's collaborators, Jacques Van Melkebeke, also appears on some of the albums.

The cameos of other Hergé characters deserve special mention, such as Quique and Flupi (Quick and Flupke), who occasionally appear in some albums: in Tintin in the Congo (initial vignette); in The Mysterious Star (page 20) and in The Seven Crystal Balls (page 61).

Translation into other languages

Apart from French, the first language in which The Adventures of Tintin were published was Portuguese. Thanks to Father Abel Varzim, known to Hergé for having studied at the University of Leuven, between April 16, 1936 and May 20, 1937 it was published in the magazine O Papagaio, directed by Adolfo Simões Müller, Tim-Tim na América do Norte (Tintin in America). In O Papagaio, Tintin's adventures appeared in color before even than in his country of birth. The adaptation to Portuguese entailed some changes: the protagonist presented himself as a reporter, not for Le Vingtième Siècle, but for O Papagaio itself, and the quirky Portuguese Oliveira da Figueira who It appears in The Pharaoh's Cigars and was converted into Spanish.

In 1952, the Casterman publishing house translated the albums The Secret of the Unicorn and Red Rackham's Treasure into three European languages (English, Spanish and German). These editions, however, were barely distributed, and their copies are today highly sought after by collectors. At the end of the decade, however, the adventures of Tintin began to be published by local publishers: Methuen, in the United Kingdom (1958); and Editorial Juventud, in Spain; In Germany, comics appeared serially in magazines starting in 1953.

Currently, the series has been translated into more than 70 languages and dialects, including, in addition to those mentioned, Afrikaans, Arabic, Bulgarian, Catalan, Czech, Chinese, Korean, Danish, Slovenian, Slovak, Esperanto, Greek, Finnish, Hebrew, Hungarian, Italian, Icelandic, Indonesian, Dutch, Japanese, Latvian, Lithuanian, Malay, Mongolian, Norwegian, Persian, Polish, Romanian, Russian, Serbo-Croatian, Swedish, Tibetan, Turkish and Vietnamese. The first translations into regional languages were to Catalan and Basque in Spain and in France to Breton and Occitan, and many others followed (Corsican, Galician, Alsatian, etc.) There are even translations of the albums into the Brussels dialect.

In the translations the characters often change their names. For example, Professor Tornasol (Tryphon Tournesol in the original), one of the characters whose name undergoes the most transformations in the different versions of the series is called in English Cuthbert Calculus; in German Balduin Bienlein; in Dutch Trifonius Zonnebloem; in Finnish Teofilus Tuhatkaumo; and in Portuguese Trifólio Girassol.

Spanish editions

- See also: Tintin Albums

The first edition, very little known, of two titles in Spanish of the adventures of Tintin, The Secret of the Unicorn and The Treasure of Rackham the Red, ran to responsibility of Editorial Casterman itself, in 1952, six years before Editorial Juventud took charge of the translation and marketing in Spain. Both albums would have been released at the same time as the English and German editions, although due to the lack of success they had in the market, Casterman did not continue publishing the adventures of Tintin in Spanish. Because this rare edition presents a Spanish translation identical to the one that Editorial Juventud would present when it took charge of the edition, the hypothesis is considered that the pages of Casterman's unsold albums in Spanish were used at the time for the Youth edition.

Later, The Adventures of Tintin were serialized in the magazines 3 Amigos and Blanco y Negro between 1957 and 1961.

The publication in albums for Spanish-speaking countries was carried out, starting in 1958, by the Barcelona-based Editorial Juventud. The Spanish translator of all the albums was Concepción Zendrera, daughter of the founder and owner of the publishing house, José Zendrera Date. Zendrera was also responsible for the Spanish names of some characters, such as Hernández and Fernández (in the original, Dupond and Dupont) or Silvestre Tornasol (Tryphon Tournesol in the original).

The order of appearance in Spain of the Tintin albums was as follows:

- 1958: The sceptre of Ottokar, Objective: The Moon

- 1959: The Secret of the Unicorn, Landing on the Moon

- 1960: The mystery star, The Treasure of Rackham the Red

- 1961: Black island, The Tornasol affair

- 1962: Tintin in Tibet, Coke Stock, Tintin in the country of black gold

- 1963: The crab of the gold clamps

- 1964: The cigarettes of the Pharaoh, The jewels of the Castafiore

- 1965: The Blue Lotus, The broken ear

- 1966: The seven crystal balls, The Temple of the Sun

- 1968: Redes en América, Tintin in the Congo

- 1969: Flight 714 to Sydney

- 1977: Tintin and the Picars

In 2001, the Belgian publisher Casterman decided to directly publish the Tintin albums throughout the world. This caused a conflict with the Juventud publishing house, which has owned the rights for Spanish-speaking countries for more than forty years. For this reason, at the end of the 2000s, two different editions in Spanish coincided in bookstores: the of Juventud, with the translation by Concepción Zendrera, in album format (30 x 23 cm), and that of Casterman, in a reduced format (22 x 17 cm) and with a new translation. In addition, Casterman has also published, in the same format, the black and white versions of the first albums, from Tintin in the Land of the Soviets to The Crab with the Golden Claws.

Unofficial albums

The popularity of the character has caused the appearance over time of unofficial albums, that is, not authorized by Hergé or his heirs. There is a wide range of unofficial Tintin albums: from pirated editions of official albums to pastiches and parodies, some made by authors who later became well-known cartoonists, such as the Canadian artist Yves Rodier. Despite the aforementioned versions, the Hergé Foundation, custodian of the copyright, has not authorized the publication of any of them as official material, limiting their publication to clandestine channels.

Pirate editions

At first, the pirate editions focused mainly on the first album of the series, Tintin in the Land of the Soviets, which for a long time Hergé refused to reissue due to its content. political. In China, where the Tintin albums were not officially released until 2001, pirated editions have been widespread since the 1980s.

Parodies

As for parodies, the first of some importance was Tintin in the Land of the Nazis, published in 1944 by the Belgian newspaper L'Insoumis, in which his own characters accuse Hergé of collaboration during the German occupation of Belgium.

Some parodies, such as Tintin in Thailand or The sexual life of Tintin, develop the character's sexuality, an aspect absolutely absent from the albums, developing erotic stories or even pornographic. There are also numerous political parodies, such as Tintin in El Salvador (about the guerrilla in this Spanish-American country), Greenmore's Harps (about the Irish conflict), or Tintin in the Gulf (about the Iraq war), to name just a few.

Imitators

The Canadian Yves Rodier made in 1986 (at the age of 19) a finished version in color of Tintin and the Alfa-Art, extremely respectful of Hergé's work, with the intention of seeing it authorized its publication by the author's heirs. However, he was denied permission. Later, Rodier produced new Tintin albums, including Tintin et le Lac de la Sorcière and Tintin reporter pigiste au XX. This last story, only three pages long, takes place at the beginning of the series and tells how Tintin became famous and was sent to the country of the Soviets.

Another notable Hergé imitator is Harry Edwood, who draws covers of non-existent albums and new adventures of the character, such as The Voice of the Lagoon and The Elves of Marlinspike.

Pastiches

Some other artists have dedicated themselves to making pastiches of the Tintin albums. In that case, it involves the use of Hergé's original sketches (mainly the figures of his characters) to place them in other environments and tell new stories. This is the case, for example, of Ovni 666 pour Vanuatu which begins with the same first pages as the original Flight 714 for Sydney. The already mentioned The Harps of Greenmore also begins as a pastiche and then continues with an original drawing. A similar case is that of Tintin in Barcelona.

On the occasion of Hergé's death, in 1983, the French comic magazine À SUIVRE published a special issue, in which comics honoring Tintin appeared by authors such as Jacques Tardi, René Pétillon, Regis Franc, François Boucq, Frank Margerin, Jacques Martin, Ted Benoit and Daniel Torres. In Spain, these stories were published by the Cairo magazine shortly after.

On January 28, 1999, a pastiche titled Objectif Monde< was published in the Parisian newspaper Le Monde, on the occasion of the Angoulême International Comics Festival and the seventieth anniversary of Tintin. /i>, work of Didier Savard. This pastiche is an exception in that its publication was authorized by the Hergé Foundation: the 26-page work tells the story of a Le Monde journalist, Wzkxy, called "Tintin" because of his love for the character, and is full of allusions to the series.

Adaptations to other media

Cinema

Several film adaptations of the series have been made, both in cartoons and live-action films. The two films produced with real actors, Tintin and the Mystery of the Golden Fleece (1961) and Tintin and the Blue Oranges, were developed from original scripts and not from the albums of the series. Hergé did not personally intervene in its production. On the contrary, all the animated films, with the exception of one (Tintin and the Lake of Sharks), are adaptations of the albums of the series.