Tenerife air disaster

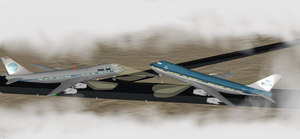

The Tenerife air disaster (also known as the Los Rodeos accident) refers to a collision between two Boeing 747 aircraft that occurred on March 27, 1977 at the Los Rodeos airport (now Tenerife-North), in the municipality of San Cristóbal de La Laguna, in the north of the Spanish island of Tenerife, in which five hundred and eighty-three people died.

It was the most serious air accident of 1977, the most catastrophic in an air collision on the ground, and the deadliest in Spain. For Pan Am it was the worst plane crash involving a US aircraft, far more than American Airlines Flight 191 two years later. For KLM it was the deadliest accident involving a Dutch aircraft after the accident involving Martinair Flight 138 three years earlier. It is also the worst air accident worldwide in the history of aviation.

The crashed planes were flight 4805, a charter flight of the Dutch airline KLM, which was flying from Schiphol airport in Amsterdam (Netherlands), heading to Gran Canaria airport (Spain), and flight 1736, a regular Pan Am flight, which flew from John F. Kennedy International Airport in New York, coming from Los Angeles International Airport (United States), to the airport from Gran Canaria.

A bomb alert at the Gran Canaria airport carried out by Canarian independentists MPAIAC, an armed group of the Movement for Self-Determination and Independence of the Canary Islands, caused many flights to be diverted to Los Rodeos, including the two planes involved in the bombing. the accident. The airport quickly became congested with parked planes blocking the only taxiway and forcing departing planes to taxi down the runway. Patches of thick fog drifted across the airfield, so there was no visibility between the aircraft and the control tower.

The collision occurred as the KLM plane began its takeoff roll while the Pan Am plane, shrouded in fog, was still on the runway and about to exit onto the taxiway. Noticing their presence on the takeoff runway, the KLM plane tried to rise to fly over the Pan Am plane and almost succeeded, but ended up hitting it. The resulting crash killed all the passengers on board the KLM 4805 and the vast majority of the Pan Am 1736, of which only sixty-one people who were sitting in the front of the aircraft would survive.

The subsequent investigation by the Spanish authorities concluded that the main cause of the accident was the KLM captain's decision to take off, mistakenly believing that an air traffic control (ATC) take-off clearance had been issued. Dutch investigators placed greater emphasis on the mutual misunderstanding in radio communications between the KLM team and ATC, but ultimately KLM admitted that its team was responsible for the accident and the airline eventually agreed to financially compensate the families of all the victims. victims.

The incident had a lasting impact on the aviation industry, which highlighted the vital importance of using standardized phraseology in radio communications. Cockpit procedures were also revised, contributing to the establishment of crew resource management as a fundamental part of airline pilot training.

Background

While the planes were heading to Gran Canaria, a bomb in the passenger terminal of the Gran Canaria airport exploded at 1:15 p.m. local time (2:15 p.m. in Madrid) on the day of the accident. Later there was a second bomb threat, so the local authorities cautiously closed the airport for a few hours. The explosive had supposedly been planted by militants of the Movement for Self-Determination and Independence of the Canary Islands (MPAIAC), although the person in charge of said clandestine organization denies it, instead accusing the Civil Guard of having fabricated the attack to discredit them.

Flights KLM 4805 and PAA 1736, like many others, were diverted to Los Rodeos airport on the neighboring island of Tenerife. Back then, Los Rodeos was still too small to comfortably absorb such congestion. Its facilities were very limited, a single takeoff runway and its controllers were not used to so many planes, much less Jumbos, and it was Sunday, so there were only two on duty. They did not have ground radar and the runway lights were out of order. In addition, the Tenerife South airport, which had been planned to relieve congestion in the old Tenerife airport, was still under construction and would not open until November 1978.

When the Gran Canaria airport was reopened, the flight crew of Pan Am 1736 proceeded to request permission to take off and fly there, but were forced to wait because KLM 4805 had requested permission to refuel and blocked the exit to the runway. Right at the end of the upload, notification was received that the police had closed the Gran Canaria airport again. The two 747 planes were forced to wait another two hours. The Dutch plane had filled its tanks with 55,000 liters of fuel, an excessive amount for the situation, but which would allow it to avoid having to refuel in Gran Canaria, since its final destination was Amsterdam.

At 16:56, the Dutch pilot of the KLM flight, Jacob Veldhuyzen van Zanten, was given permission to start his engines and move down the main runway, exit through the third exit (C1 and C2 had planes on them) and reach the end. Later, the controller, to make the maneuver more agile and after repeating the order to the KLM, decided to correct and order it to continue along the main track without deviating, and at the end of it to make a 180º turn (backtrack ) and wait for confirmation of the takeoff of the route. Three minutes later, PAA 1736 received instructions to proceed along the takeoff runway, leave it when it reached the third exit on its left, and confirm its departure once the maneuver was completed. But PAA 1736 missed the third exit (it is assumed that it did not see it due to the dense fog or that the necessary maneuver was in itself very complex for a jumbo jet, added to the absence of lights on said runway) and continued towards the fourth. Furthermore, his speed was abnormally reduced because of the prevailing fog.

Once he had completed the turn of his aircraft, van Zanten raised the engines (an increase in gases was recorded in the black box) and his co-pilot warned him that they still did not have clearance to take off. Van Zanten, recently an instructor and accustomed to teaching new pilots to give their own authorizations since there is no control tower, asks him to speak with the Los Rodeos tower and the communication indicates that they are at the head of the runway 30 waiting to take off. Los Rodeos gives them the route to follow, an Air Traffic Control Clearance (ATCC), and the co-pilot repeats it, ending with an unorthodox "we are in (position) for takeoff". Literally: «Roger sir, we are cleared to the Papa beacon flight level nine zero, right turn out zero four zero until intercepting the three two five» (Okay, sir, we are cleared at flight level of the Papa nine zero beacon, deviation to the right zero four zero until intercepting the three two five), (Gran Canaria VOR). "We are now at take-off." (Now we are at takeoff), especially this last sentence does not make any sense without the authorization of the tower. When the research teams from Spain, the United States and the Netherlands listened jointly and for the first time to the recording from the control tower, nobody or almost nobody understood that with this transmission they meant that it was taking off.

At that moment, and while his co-pilot completed the readback, that is, the repetition of the instructions received by the control tower with its controller, Van Zanten, without a takeoff permit or take off clearance, began filming by releasing the brakes, as recorded by the black box. When his co-pilot finished the snack, and with the plane already running, he qualified: " We're going ". The controller answered the receipt of the repetition of his ATC authorization message in the following manner: «Okay». And 1.89 seconds later he added: " Wait for takeoff , I'll call you ".

The control tower then asked PAA 1736 to notify it as soon as the runway had been cleared: «Papa Alfa one seven three six report runway free». This was heard in the cabin of the KLM. A second later, PAA replied: "Okay, we'll notify you when we release it", a response that was heard in the KLM cabin. The control tower replied: "Thank you". Right after this, the Dutch flight engineer and co-pilot were assailed by doubts that the runway was really clear, to which Captain Jacob Veldhuyzen van Zanten responded with an emphatic: "Oh, ya », and perhaps believing it difficult for an expert pilot like him to make a mistake of this magnitude, neither the co-pilot nor the flight engineer raised more objections. Thirteen seconds later, the fatal collision occurred.

The control tower answered the calls from the IB-185 and BX-387 and waited for the communication from PANAM 1736 informing of "runway free", it received information from two aircraft located in the parking lot that there was a fire in an unspecified place in the camp, sounded the alarm, informed the fire and health services, and spread the news of the emergency situation; He then called the two planes he had on the runway, from which he received no reply.

The accident

The impact occurred about thirteen seconds later, at exactly 17:06:50 UTC, after which air traffic controllers were unable to communicate with either aircraft again. Due to the heavy fog, the pilots of the KLM plane could not see the Pan Am plane taxiing towards them. Flight KLM 4805 was visible from PAA 1736 approximately 8 and a half s before the collision, and its pilot tried to accelerate to leave the runway, but at that altitude the crash was already unavoidable.

The KLM was already fully airborne when the impact occurred, at about 200 mph, but it obviously didn't reach enough altitude to avoid disaster - experts estimate 25 more feet (7.62 meters). they would have been enough. Its front end struck the top of the other Boeing, ripping off the cabin roof and upper passenger deck, whereupon the two engines struck the Pan Am plane, instantly killing most of the passengers seated on the top. rear.

The Dutch plane continued to fly after the collision, crashing to the ground some 150 m from the crash site, and skidding down the runway an additional 300 m. A violent fire broke out immediately (remember that the KLM had refueled minutes before) and despite the fact that the impacts against the Pan Am and the ground were not extremely violent, the 248 people on board the KLM died in the fire, as well as 335 of the 396 people aboard the Pan Am, including nine who later died of their injuries. There was a passenger on the Dutch KLM plane who was saved thanks to the fact that when all the passengers got off the plane to take the air before continuing to Gran Canaria, she refused to get back on because she lived in Tenerife.

The weather conditions made it impossible for the accident to be seen from the control tower, from where only one explosion was heard followed by another, without making its location or causes clear.

| Translation of the transcription of communications and the comments of crew members in the cabins of both aircraft | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| The time is based on the voice recording (CVR) of the KLM cabin. The "(-)" parentheses indicate words that are not clearly heard and the "(---)" double parentheses are clarifications of the final report and the terminology used in aviation. | |||

| Time | Speaking | Translation | Transcription in original language |

| 16:58:14 | RADIO KLM | About KLM four eight zero five on land in Tenerife. | Approach KLM four eight zero five on the ground in Tenerife. |

| 16:58:21 | Control tower | KLM four eight zero five, roger (received). | KLM -ah-four eight zero five, roger. |

| 16:58:25 | RADIO KLM | We need backtrack on 12 to take off at Track 30. | We require backtrack on 12 for takeoff Runway 30. |

| With backtrack it refers to using the same track to reel and—after a 180° turn—for takeoff. Pista 12 and Pista 30 are actually the same main track, only in opposite senses: the 12 in the southeast and the 30 in the northwest sense. | |||

| 16:58:30 | Control tower | Okay, four eight zero five... Roll back to the Pista 30 waiting point. Reel on the track and exit (third) track to your left. | Okay, four eight zero five... taxi... to the holding position Runway 30. Taxi into the runway and -ah- leave runway (third) to your left. |

| 16:58:47 | RADIO KLM | All right, sir, (entering) on the track at this time and in the first (track) we left the track again towards the beginning of Track 30. | Roger, sir, (entering) the runway at this time and the first (taxiway) we, we go off the runway again for the beginning of Runway 30. |

| 16:58:55 | Control tower | Okay, KLM eight zero... correction, four eight zero five, reel straight down the track and do backtrack. | Okay, KLM eight zero -ah- correction, four eight zero five, taxi straight ahead -ah- for the runway and -ah- make -ah- backtrack. |

| 16:59:04 | RADIO KLM | Okay, make a backtrack. | Roger, make a backtrack. |

| 16:59:10 | RADIO KLM | KLM four eight zero five is now on the track. | KLM four eight zero five is now on the runway. |

| 16:59:15 | Control tower | Four eight zero five, roger. | Four eight zero five, roger. |

| 16:59:28 | RADIO KLM | Approximation, you want us to turn left on Charlie 1, exit Charlie 1? | Approach, you want us to turn left at Charlie 1, taxiway Charlie 1? |

| With Charlie 1 it refers to the first side exit, of the four crossing the main track. | |||

| 16:59:32 | Control tower | Negative, negative, right reel until the end of the track and make a backtrack. | Negative, negative, taxi straight ahead—ah—up to the end of the runway and make backtrack. |

| 16:59:39 | RADIO KLM | Okay, sir. | Okay, sir. |

| 17:01:57 | RADIO PAN AM | Tenerife, the Clipper one seven three six. | Tenerife, the Clipper one seven three six. |

| 17:02:01 | Control tower | Clipper one seven three six, Tenerife. | Clipper one seven three six, Tenerife. |

| 17:02:03 | RADIO PAN AM | We were instructed to contact you and also roll the track, is that correct? | Ah—we were instructed to contact you and also to taxi down the runway, is that correct? |

| 17:02:08 | Control tower | Affirmative, turn down the track and exit the third track, third to your left (conversation of background in the tower)). | Affirmative, taxi into the runway and—ah—leave the runway third, third to your left, (background conversation in the tower)). |

| 17:02:16 | RADIO PAN AM | Third left, right. | Third to the left, okay. |

| 17:02:18 | George Warns (Pan Am flight mechanic) | Third, he said. | Third, he said. |

| 17:02:18 | NN (unidentified person in the Pan Am cabin) | Three. | Three. |

| 17:02:20 | Control tower | (Te) turn left. | (Th)ird one to your left. |

| 17:02:21 | Victor Grubbs (Pan Am Capitán) | I think he said first. | I think he said first. |

| 17:02:26 | Robert Bragg | I'll ask you again. | I'll ask him again. |

| 17:02:26 | NN (Pan Am) | ... (no understanding) | (*) |

| 17:02:32 | Bragg (Pan Am) | Turn left. | Left turn. |

| At that time, the KLM was on the main track until the end of the tour and the Pan Am had received reel instructions behind, in the same sense, to go out on the third track. Behind were other planes waiting to enter the Track 12, with another plane waiting at Exit 1 and another on Exit 2, while Exit 3 and 4 were clear. | |||

| 17:02:33 | Grubbs (Pan Am) | I don't think they have the minimum (visibility) for taking off at any time. | I don't think they have takeoff minimums anywhere right now. |

| 17:02:39 | Grubbs (Pan Am) | What really happened there today? | What really happened over there today? |

| 17:02:41 | NN (Pan Am), possibly a company employee. | They put a bomb (in) the terminal, sir, right where the billing counters are. | They put a bomb (in) the terminal, sir, right where the check-in counters are. |

| 17:02:46 | Grubbs (Pan Am) | Well, we asked them then if we could wait and... I guess you got the word, we landed here. | Well, we asked them if we could hold and—uh—I guess you got the word, we landed here... |

| 17:02:46 | NN (Pan Am) | ... (no understanding) | (*) |

| 17:02:49 | Control tower | KLM four eight zero five, how many exits did it happen? | KLM four eight zero five, how many taxiway -ah- did you pass? |

| 17:02:55 | RADIO KLM | I think we just passed Charlie 4 now. | I think we just passed Charlie 4 now. |

| 17:02:59 | Control tower | Well... at the end of the track make an eighty (180 degrees) and stand ready for ATC authorization ((Air driver's authority) (there is a background conversation in the tower). | O.K.... at the end of the runway make one eighty and report -ah- ready -ah- for ATC clearance ((background conversation in the tower)). |

| 17:03:09 | Bragg (Pan Am) | The first is a 90-degree turn. | The first one is a 90-degree turn. |

| 17:03:11 | Grubbs (Pan Am) | Yeah, okay. | Yeah, okay. |

| 17:03:12 | Bragg (Pan Am) | Must be the third... I'll ask you again. | Must be the third... I'll ask him again. |

| 17:03:14 | Grubbs (Pan Am) | Good. | Okay. |

| 17:03:16 | Grubbs (Pan Am) | We could probably get in, it's... | We could probably go in, it's ah... |

| 17:03:19 | Bragg (Pan Am) | You must make a ninety-degree turn. | You gotta make a 90-degree turn. |

| 17:03:21 | Grubbs (Pan Am) | Yeah, uh. | Yeah, uh. |

| 17:03:21 | Bragg (Pan Am) | I turn 90 degrees to turn this around... This one here is a 45. | Ninety-degree turn to get around this... this one down here, it's a 45. |

| The first officer Bragg has a track map and refers to output number 3, which is 45 degrees from the main track, after the first two exits to 90 degrees. However, output 3 is not at 45 degrees with respect to the Pan Am plane, but at 135 degrees, while the following output (number 4) is at 45 degrees in relation to the direction of the aircraft. | |||

| 17:03:29 | RADIO PAN AM | Could you confirm that you want the Clipper one seven three six to turn left on the "third" intersection? (the word "third" is pronounced with emphasis) | Would you confirm that you want the clipper one seven three six to turn left at the third intersection? (("third" drawn out and emphasized) |

| 17:03:35 | Grubbs (Pan Am) | One, two. | One, two. |

| 17:03:36 | Control tower | Third, sir; one, two, three, third, third. | The third one, sir; one, two, three, third, third one. |

| 17:03:38 | NN (Pan Am) | One, two (four). | One two (four). |

| 17:03:39 | Grubbs (Pan Am) | Good. | Good. |

| 17:03:39 | RADIO PAN AM | All right, thanks. | Very good, thank you. |

| 17:03:40 | Grubbs (Pan Am) | That's what we need, the third. | That's what we need right, the third one. |

| 17:03:42 | Warns (Pan Am) | (in Spanish) One, two, three. | One, two, three. |

| 17:03:44 | Grubbs (Pan Am) | (in Spanish) One, two, three. | One, two, three. |

| 17:03:44 | Warns (Pan Am) | (in Spanish) Three, yeah. | Three-uh-yeah. |

| 17:03:46 | Grubbs (Pan Am) | Right. | Right. |

| 17:03:47 | Warns (Pan Am) | We'll still do it. | We'll make it yet. |

| 17:03:47 | Control tower | ...er ((sic) Seven one three six report on leaving the lead. | ...er seven one three six report leaving the runway. |

| 17:03:49 | Bragg (Pan Am) | Flap wings? | Wing flaps? |

| 17:03:50 | Grubbs (Pan Am) | Ten, indicates ten, the main lights on the edge are green. | Ten, indicate ten, leading edge lights are green. |

| 17:03:54 | NN (Pan Am) | Understood. | Get that. |

| 17:03:55 | RADIO PAN AM | Clipper one seven three six. | Clipper one seven three six. |

| 17:03:56 | Bragg (Pan Am) | Scratch absorber and instrument? | Yaw damp and instrument? |

| 17:03:58 | Grubbs (Pan Am) | Bob, we'll have a left... | Ah- Bob, we'll get a left one... |

| 17:03:59 | Bragg (Pan Am) | I have a left. | I got a left. |

| 17:04:00 | Grubbs (Pan Am) | Did you? | Did you? |

| 17:04:00 | Bragg (Pan Am) | And I need a right. | And -ah- need a right. |

| 17:04:02 | Grubbs (Pan Am) | I'll give you a little... | I'll give you a little... |

| 17:04:03 | Bragg (Pan Am) | Put some lean on this. | Put a little aileron in this thing. |

| 17:04:05 | Grubbs (Pan Am) | Okay, here's a left and I'll give you a right right here. | Okay, here's a left and I'll give you a right one right here. |

| 17:04:09 | Grubbs (Pan Am) | Okay, turn right and left. | Okay, right turn right and left yaw. |

| 17:04:11 | Bragg (Pan Am) | Check left-handed. | Left yaw checks. |

| 17:04:12 | Grubbs (Pan Am) | Well, here are the helms. | Okay, here's the rudders. |

| 17:04:13 | Grubbs (Pan Am) | Here are two lefts, center, two right center. | Here's two left, center, two right center. |

| 17:04:17 | Bragg (Pan Am) | Check. | Checks. |

| 17:04:19 | Bragg (Pan Am) | Controls. | Controls. |

| 17:04:19 | Grubbs (Pan Am) | I haven't seen any yet! | Haven't seen any yet! |

| 17:04:20 | Bragg (Pan Am) | Me neither. | I haven't either. |

| 17:04:21 | Grubbs (Pan Am) | They're free, the indicators are checked. | They're free, the indicators are checked. |

| 17:04:24 | Bragg (Pan Am) | There's one. | There's one. |

| 17:04:25 | Grubbs (Pan Am) | There's one. | There's one. |

| 17:04.26 | Grubbs (Pan Am) | That's 90 degrees. | That's the 90-degree. |

| 17:04:28 | NN (Pan Am) | Good. | Okay. |

| At that time Captain Grubbs reached to see between the fog the first exit, Charlie 1, and goes on to the exit track number 3. | |||

| 17:04:34 | Bragg (Pan Am) | Final weight and balance? | Weight and final balance? |

| 17:04:34 | NN (Pan Am) | ... (no understanding) | (* *) |

| 17:04:37 | Reading of black boxes | ((A sound similar to the compensation stabilizer is heard) | ((Sounds similar to stabilizer trim) |

| 17:04:37 | Grubbs (Pan Am) | We were gonna put that in four and a half. | We were gonna put that on four and a half. |

| 17:04:39 | Warns (Pan Am) | We have four and a half and weigh five thirty-four. ((Sound of the compensation stabilizer) | We got four and a half and we weigh five thirty four. (sound of stabilizer trim) |

| 17:04:44 | Bragg (Pan Am) | Four and a half on the right. | Four and a half on the right. |

| 17:04:46 | Bragg (Pan Am) | Check the engineer's tour. | Engineer's taxi check. |

| 17:04:48 | Warns (Pan Am) | The check of the tour is complete. | Taxi check is complete. |

| 17:04:50 | Bragg (Pan Am) | Take-off and exit instructions? | Takeoff and departure briefing? |

| 17:04:52 | Grubbs (Pan Am) | Well, it's gonna be standard. We're going straight there until we get to 3500 feet, then we're gonna make that investment and go back to... 14. | Okay, it'll be standard. We gonna go straight out there till we get 3,500 feet, then we're gonna make that reversal and go back out to... 14. |

| 17:04:58 | Control tower | ...eight seven zero five and Clipper one seven... three six, for your information, the centreline lighting (floor axis light system) It's off duty. (the transmission of the tower is readable though slightly broken). | —m eight seven zero five and Clipper one seven... three six, for your information, the centre line lighting is out of service. (APP transmission is readable but slightly broken.) |

| 17:05:05 | RADIO KLM | Copy that. | I copied that. |

| 17:05:07 | RADIO PAN AM | Clipper one seven three six. | Clipper one seven three six. |

| 17:05:09 | Grubbs (Pan Am) | We have central line marks (only) ((though he could say "we don't have") They count the same as... We need 800 meters if they don't have that central line... I read that at the back (of this) a moment ago. | We got centerline markings (only) ((could be "don't we")) they count the same thing as... we need eight hundred metres if you don't have that centerline... I read that on the back (of this) just a while ago. |

| 17:05:22 | Grubbs (Pan Am) | That's 2 ((refers to exit track Charlie 2)). | That's two. |

| 17:05:23 | Warns (Pan Am) | Yeah, that one over there is 45 (b). | Yeah, that's 45 there. |

| 17:05:25 | Grubbs (Pan Am) | Yeah. | Yeah. |

| 17:05:26 | Bragg (Pan Am) | That's this one here. | That's this one right here. |

| 17:05:27 | Grubbs (Pan Am) | (Yes) I know. | (Yeh)I know. |

| 17:05:28 | Warns (Pan Am) | Good. | Okay. |

| 17:05:29 | Warns (Pan Am) | The next one's almost 45, uh, yeah. | Next one is almost 45, huh, yeah. |

| 17:05:30 | Grubbs (Pan Am) | But it comes out... | But it goes... |

| 17:05:32 | Grubbs (Pan Am) | Yeah, he's coming... ahead, I think he's gonna leave us on (the) track. | Yeah, but it goes... ahead, I think (it's) gonna put us on (the) taxiway. |

| 17:05:35 | Warns (Pan Am) | Yeah, just a little bit, yeah. | Yeah, just a little bit, yeah. |

| 17:05:39 | NN (Pan Am) | Okay, sure. | Okay, for sure. |

| 17:05:40 | Bragg (Pan Am) | Maybe he, maybe he counts these three. ((or you can say "maybe he tells that they are three"). | Maybe he, maybe he counts these (are) three. |

| 17:05:40 | NN (Pan Am) | Uh. | Huh. |

| 17:05:44 | NN (Pan Am) | I like this one. | I like this. |

| At that time, the KLM is located at the southeast end of the main track pointing directly towards the Pan Am (probably just over a thousand meters away one from another), which seeks to enter one of the cross-sectional outputs in the low visibility. In the Pan Am they seem unclear what way to take (if 3 or 4) and finally the captain decides for Charlie 4, which leads the plane to continue a few more meters on the main track. As recorded below, three seconds before the KLM co-pilot warned the captain that they still had no control of the tower for takeoff, just after the black box recorded an increase of gases that usually precede the takeoff. | |||

| 17:05:41 | Klaas Meurs (KLM couple) | Wait a minute, we don't have an ATC authorization. | Wait a minute, we don't have an ATC clearance. |

| 17:05:42 | Jacob Veldhuyzen van Zanten (KLM Captain) | No, I know that. Go ahead, ask. | No, I know that. Go ahead, ask. |

| 17:05:44 | RADIO KLM | The KLM... four eight zero five is ready to take off... and we're waiting for our ATC authorization. | Uh, the KLM... four zero five is now ready for take-off... uh and we're waiting for our ATC clearance. |

| 17:05:53 | Control tower | KLM 8 7 ((sic) zero five... are authorized to rise Papa Beacon and maintain flight level nine zero, turn right after takeoff proceed to zero four zero until intercept the radial three two five of Las Palmas VOR. | KLM eight seven * zero five uh you are cleared to the Papa Beacon climb to and maintain flight level nine zero right turn after take-off proceed with heading zero four zero until intercepting the three five radial from Las Palmas VOR. |

| 17:06:09 | RADIO KLM | Ah, okay, sir, we're enabled to flight level Papa Beacon nine zero, turn right to zero four zero until we intercept three two five and now we're (in takeoff). | Ah roger, sir, we're cleared to the Papa Beacon flight level nine zero, right turn out zero four zero until intercepting the three two five and we're now (at take-off). |

| In fact, the tower authorizes to take a certain route after takeoff, but not to take off (take-off clearance). And the KLM response ("we're now at take-off") is not within the standard aviation language. | |||

| 17:06:11 | Reading of black boxes | (KLM brakes are released) | (Brakes of KLM 4805 are released.) |

| 17:06:13 | Veldhuyzen van Zanten (KLM) | (in Dutch) We're leaving. | We win. |

| 17:06:14 | Reading of black boxes | ((Sound of engines starting to accelerate) | ((Sound of engines starting to accelerate) |

| 17:06:18 | Control tower | Good. | Okay. |

| The answer of the tower ("OK") is not of the standard language either. According to the notes of the official investigation, the controller would have assumed that since the KLM they announced that they were in a position of take-off ("we're now at take-off position") when he only said "now we are in take-off" ("we're now at take-off"). An instant later (at 17:06:19) a crucial problem is unleashed: the control tower and the Pan Am speak on radio simultaneously, which makes the KLM cabin hear a loud sound for almost four seconds. For that reason, the following communications were probably not heard in the KLM. | |||

| 17:06:20 | Control tower | Wait for the takeoff... I'll call him. | Stand by for takeoff... I will call you. |

| 17:06:20 | RADIO PAN AM | And we're still rolling down the track, the Clipper one seven three six. | And we're still taxiing down the runway, the clipper one seven three six. |

| 17:06:21 | Grubbs (Pan Am) | No, uh... | No, uh. |

| The following messages were perfectly audible to the KLM - which was already in the process of taking off - warning that the Pan Am was still on track. | |||

| 17:06:25 | Control tower | Papa Alpha one seven three six report clear track. | Ah- Papa Alpha one seven three six report runway clear. |

| 17:06:26 | RADIO PAN AM | Well, we'll report when we're clear. | Okay, we'll report when we're clear. |

| 17:06:31 | Control tower | Thank you. | Thank you. |

| 17:06:32 | Willem Schreuder (KLM flight mechanic) | (in Dutch) It's not clear, then? | Is hij er niet af dan? |

| 17:06:34 | Veldhuyzen van Zanten (KLM) | (in Dutch) What did you say? | Wat zeg je? |

| 17:06:34 | NN (KLM) | Yeah. | Yup. |

| 17:06:34 | Schreuder (KLM) | (in Dutch) Isn't that Pan American clear? | Is hij er niet af, die Pan American? |

| 17:06:35 | Veldhuyzen van Zanten (KLM) | (in Dutch) Oh, yeah. | Jawel. (emphatic) |

| 17:06:38 | Grubbs (Pan Am) | There he is... look at him. God, that son of a bitch is coming! | There he is... look at him. God disaster that son of a bitch is coming! |

| 17:06:40 | Bragg (Pan Am) | Get out! Get out! | Get off! Get off! |

| 17:06:43 | Reading of black boxes | (KLM airplane lifts the nose) | (Plane nose pointing up) |

| 17:06:44 | NN (pan Am) | (Exclamations) | (Exclamations) |

| 17:06:46 | Reading of black boxes | ((The KLM plane tries to turn right, 0.46 seconds later left and 1.54 seconds before impact on the right) | ((Increased direction toward the right is observed)) ((0.46 seconds later, a curving of the plane to the left is seen) ((1.54 seconds before impact, a roll to the right is observed) |

| 17:06:47 | Grubbs (Pan Am) | (Exclamation) | (Exclamation) |

| 17:06:49 | Reading of black boxes | (Impacto) | (Impact) |

| End of recording. | |||

Moments after the collision, an aircraft on the parking apron alerted the control tower that it had seen fire. The tower sounded the fire alarm immediately and, still not knowing the situation of the fire, they informed the fire brigade. They headed for the area at the fastest possible speed, which due to the heavy fog was still too slow, even without being able to see the fire, until they could see the light of the flames and feel the strong radiation of heat. As the fog cleared a bit, they could see for the first time that there was a plane completely engulfed in flames. After beginning to extinguish the fire, the fog continued to clear and they could see another light, which they thought was part of the same burning plane that had broken off. They divided the trucks and as they approached what they thought was a second source of the same fire, they discovered a second plane on fire. They immediately concentrated their efforts on this second plane, since on the first it was completely impossible to do anything.

As a result, and despite the great extent of the flames on the second plane, they were able to save the left side, from which fifteen to twenty thousand kilos of fuel were later extracted. Meanwhile, the control tower, still covered by a dense fog, was still unable to find out the exact location of the fire and whether it was one or two planes involved in the accident.

According to survivors of the Pan Am flight, including its captain Victor Grubbs, the impact was not terribly violent, leading some passengers to believe it was an explosion. A few located in the front part jumped onto the track through openings in the left side while various explosions were taking place. The evacuation, however, took place quickly and the wounded were transferred. Many had to jump directly blind and many of the survivors suffered fractures and sprains from the height of the Jumbo.

Fire trucks from the neighboring cities of La Laguna and Santa Cruz had to be used and the fire was not completely extinguished until 03:30 on March 28. In the accident, the former administrator of the Californian city of San Jose, A. P. Hamann, died along with his wife Frances Hamann and the ex-wife of Russ Meyer, Eve Meyer.

Robert Bragg, co-pilot of the Pan Am 1736, says that "taxis and private vehicles evacuated the majority of those injured by burns, transferring them to nearby hospitals". Radio and television stations, as well as radio amateur stations, also alerted health personnel to come and help at the scene of the accident. The Cabildo de Tenerife and the La Laguna City Council provided in those sad moments all the means available to deal with the personal situations of the relatives of the deceased, as well as care for the survivors. Thirty years later, these two corporations have collaborated closely with the Dutch Foundation for Relatives of Victims to materialize a sculpture project in memory of those who lost their lives on that fateful day.

Crew of the 2 planes

KLM Flight 4805

| Name | Age | Nationality |

|---|---|---|

| Captain Jacob Veldhuyzen van Zanten | 50 years | Dutch |

| First Officer Klaas Meurs | 42 years | |

| Willem Schreuder Flight Engineer | 49 years | |

| C. W. Sonneveld | ||

| A. Th. A. van Straaten | ||

| Helena Wilhelmina Toby-Fleur | ||

| B. M. Wildshut-Joosse | ||

| W. M. Keulen | ||

| M. May-Lefeber | ||

| J. H. M. Schuuemans-Timmermans | ||

| J. M. L. van Staveren | ||

| M. M. Tom-Karseboom | ||

| M. E. Viergever-Drent |

Pan Am Flight 1736

Survivors

- Captain Victor Franklin Grubbs (1920-1995) (56 years, American)

- First Officer Robert L. Bragg (1937-2017) (39 years, American)

- George W. Warns Flight Engineer (1930-1991) (46 years, American)

- Joan Jackson (American)

- Suzanne Donovan (American)

- Dorothy Kelly (American)

- Carla Johnson (American)

Deceased

- Marilyn Luker (American)

- Carol Eileen Thomas (American)

- Luisa Elena Garcia-Flood (American)

- Mari X. Asai (Japanese)

- Sachiko Hirano (Japanese)

- Miguel Pere Ángel 'Perez' Torrech (puertorriqueño)

- Françoise Colbert de Beaulieu-Greenbaum (French)

- Aysel Nafia Sarp-Buck (Turk)

- Christine Brirgitta Ekelund

Nationalities

KLM Flight 4805

The nationalities of the 234 passengers and 14 crew members included 4 different countries:

| Nationality | Passengers | Triple | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Netherlands | 220 | 14 | 234 |

| Germany | 5 | 0 | 5 |

| 5 | 0 | 5 | |

| Austria | 4 | 0 | 4 |

| Total | 234 | 14 | 248 |

Pan Am Flight 1736

The nationalities of the 380 passengers and 16 crew members included 8 different countries:

Explanations

A number of factors contributed to the accident. The main one was the bomb threat that caused the airport to be overloaded. Fatigue after long hours of waiting and the increasing tension of the situation added risk factors - the KLM captain, due to the rigidity of the Dutch rules on service time limitations, only had three hours to take off from the airport from Gran Canaria back to Amsterdam airport or the flight would have to be suspended, with the consequent chain of delays that this would entail. In addition, the weather conditions at the airport were deteriorating rapidly, which could cause the flight to be further delayed. The so-called "rush syndrome" could have affected the Dutch pilot, who began his journey down the runway without clearance to take off : he only had confirmation of the route to follow once he took off. This is the direct cause of the accident and, despite Dutch reluctance, it is the version accepted and corroborated by the black boxes of both devices.

Another contributing factor were the transmissions from the tower telling KLM to hold and from Pan Am informing that it was still taxiing on the takeoff runway, which were not clearly received in the KLM cockpit; both communications were made at the same time, by chance, so there was interference. The technical language used in the communication between the three parties was not adequate either. For example, the Dutch co-pilot did not use the proper language to indicate that they were about to take off and the air traffic controller added an OK just before asking the KLM flight to await take-off clearance.

The Pan Am also did not leave the runway at the third intersection, as instructed. In fact, seeing what the entrance to the third intersection was like, it was easy to leave the runway for a Fokker F-27, with which Iberia and Aviaco usually operated inter-island traffic at that time, but not for a Jumbo. The Pan Am pilots thought that the large dimensions made it impossible to maneuver into the third intersection. The aircraft should in fact have consulted with the tower, but this could not have been a direct cause of the accident, as it never reported that the runway was clear and reported twice that it was taxiing down she. Excessive air traffic congestion also played a role, forcing the tower to take measures that, although statutory, can on other occasions be considered potentially dangerous, such as having planes taxiing down the takeoff runway one after the other without sufficient safety distance..

It must also be taken into account that the flight from Tenerife to Gran Canaria lasts only 25 minutes, so refueling 55,500 liters of fuel made the fire produced later even greater, and suggests that the captain of flight KLM 4805 intended to avoid further delays in Gran Canaria due to air traffic problems. Being a charter flight, it should take off from the Gran Canaria airport to Amsterdam and with this amount of fuel it would have enough. The KLM plane was refueling for approximately 35 minutes, during which time the Pan Am flight could have turned around and taken off, but the Dutch plane was blocking access to the runway. If the KLM plane had loaded only the necessary fuel to go to Las Palmas (not excessively), at the moment it had to take flight to avoid the Pan Am plane, perhaps it would have managed to avoid the accident by weighing less on takeoff. The Pan Am plane, thanks to the fact that the co-pilot saw that the KLM was heading directly towards them, collaborated by trying to take the plane off the runway seconds before the crash, although due to the thick fog, the Pan Am co-pilot noticed the situation approximately between 8 and 9 seconds before the impact, just at the moment when the KLM also sighted the Pan Am plane. The KLM captain also did what had to be done: engines at full power in order to get a fast takeoff, until the point at which the tail of the plane comes to scrape over the runway. The effort to take off was in vain. The KLM engines hit the roof of the Pan Am, causing it to fall several meters away.

In the investigation carried out by inspectors from the three countries mainly involved (Spain, the Netherlands and the United States) there was unanimity in the following main conclusions:

- The captain of KLM took off without having the necessary authorization from the control tower.

- The captain of KLM did not interrupt the take-off manoeuvre, although from the Pan Am plane it was reported that they were still on the track.

- The captain of KLM replied with a resounding “yes” to his engineer when he asked (almost asserting) whether the Pan Am plane had already left the track.

- The captain of KLM seemed unclear. Once the maneuver is finished backtracking (180o turn) to take off, gassed without ATC authorization. The copilot said, "Wait, we don't have the ATC authorization yet." Then the commander stopped the plane and said to him, "Yes, I know; ask her."

- Pan Am's plane continued to roll to C4 output instead of taking C3, as indicated from the control tower.

Consequences

Due to the accident, and after the opening of the Tenerife South airport in 1978 (which was already under construction at the time of the accident), all international flights to or from the island of Tenerife were immediately prohibited from continuing to operate in The Rodeos. The dangerous airport was progressively closed for interregional domestic flights. Thus, as of November 7, 1980, only flights with origin or destination in some point of the Canary archipelago were allowed in Los Rodeos. The number of passengers in Tenerife North declined clearly in the following years until the entry into service of Binter Canarias and other regional companies (Islas Airways) that followed. After numerous costly expansions and upgrades, the airport was reopened for interregional and international domestic flights on February 14, 2003. However, Los Rodeos will never recover the pre-1978 number of flights and passengers for aviation safety reasons, and has remained relegated as the island's second airport, since currently the vast majority of air connections with the island are made through Tenerife South.

As a consequence of the accident, a series of changes took place in terms of international regulations. Since then, all control towers and pilots have been required to use common English phrases, and automatic fog navigation systems began to be installed on planes. Cockpit procedures were also changed, emphasizing joint decision-making among crew members. Specifically, it is strictly forbidden to say "take-off" ("take-off") in sentences that are not precisely those of takeoff. Instead, you should speak of "departure" ("departure").

Ground radars, non-existent on runways that were not in large cities such as London, New York or Paris, also began to be included in most airports, although they would not be in the majority until the first half of the 1980s; his absence a few years later at other airfields would be a contributing factor in other air disasters.

Several organizations were created, such as the Stichting Nabestaanden Slachtoffers Tenerife (Foundation for Relatives of the Victims of the Tenerife Accident), which was created in early 2002. This non-profit organization is dedicates itself fully to its central objective: to contribute substantially to the memory and overcoming of the plane crash of March 27, 1977 in Tenerife; expressly, it does not deal with factual and legal issues of culpability, so it does not focus its attention on imputability and responsibility.

Filmography

Special programs have been made about the accident:

- The edition of the Spanish television program Weekly report from TVE 1 when 20 years of the accident ended.

- He was dedicated to episode 12 of the first season in the American-British series Second catastrophic by National Geographic Channel, entitled "Collision on the Runway" (in Spanish "Colision on the Track" or "Tragedia at Tenerife Airport").

- Episode 3 of the season 16 of the Canadian series Mayday: aerial catastrophes National Geographic Channel, titled "Disaster in Tenerife" (Hispanoamerican) or "Accident in Los Rodeos" (Spain) portrays the accident and the entire investigation process.

- This accident is also represented in a 90-minute special that is not considered as part of the series, entitled "Crash of the Century"premiere in 2005. Scenes of the special were used in some later episodes every time the accident is mentioned. It should be mentioned that it is not available in Spanish-speaking countries.

- Brief mention of the accident in chapter 1 of the third season of the American series Breaking Bad.

- Brief mention of the accident in episode 6 of the first season of the American series Justified.

- Brief mention of the accident in episode 2269 (Temporada 10) of the Spanish series "Amar es para Siempre" in Antena 3 TV.

Literature

There are several books that mention or focus on this plane crash:

- The Rolan Galeas 1977 Rodeos.

- Professor 77. The journey interrupted.

- GCXO. 27 March 1977. The facts.

- "Terror At Tenerife" (Terror in Tenerife) published by Omega Publications in 1977 and written by two survivors, Norman Williams and George Otis.

Memorials

After the catastrophe, different commemorative monuments were erected in memory of the victims.

In 2002, the Foundation of Relatives of the Victims of the Los Rodeos Air Crash was created. On March 27, 2007, thirty years after the accident, a commemoration event was organized at the Auditorio de Tenerife in Santa Cruz de Tenerife at the foundation's initiative. On the same day, the International Commemorative Monument March 27, 1977 was inaugurated at Mesa Mota. It is an 18-meter-high structure that is shaped like a spiral staircase that ascends to heaven. It was designed by the Dutch artist Rudi van de Wint.

Other accidents in Los Rodeos

Despite the fact that the accident of March 27, 1977 is the best known, at the Los Rodeos airport there have been two other air accidents in which a considerable number of people lost their lives:

- Los Rodeos accident of 1972: 155 deceased.

- 1980 Los Rodeos accident: 146 deceased.

Contenido relacionado

Jinmu tenno

Aviation history

Louise Mountbatten-Windsor