Tempo

The terms tempo, movement or air in musical terminology refer to the speed with which a piece of music should be played. It is an Italian word meaning "time." In the scores of a work, the tempo is usually represented at the beginning of the piece above the staff.

Throughout the history of Western music, two ways of indicating tempo arose. Until the invention of the metronome, certain words such as andante, allegro, etc. were used. that provided a subjective idea of the speed of the piece and at the same time provided information about the character or expression that had to be given to the music. The invention of the metronome brought greater precision and gave rise to metronomic indications.

In current Western music it is usually indicated in beats per minute (bpm), also abbreviated as bpm, from the expression beats per minute in English. This means that a certain figure (for example, a quarter note or eighth note) is set as a beat and the indication means that a certain number of beats per minute must be played. The higher the tempo, the higher the number of beats per minute. that must be played and therefore the piece must be interpreted more quickly. Depending on the tempo, the same musical work has a more or less long duration. In a similar way, each musical figure (one black or one white) does not have a specific and fixed duration in seconds, but depends on the tempo.

History

In Europe around the first third of the XVI century, Luis de Milán indicated the tempo in his collection of music for vihuela The Master, with indications such as "something apriessa" or "measure to space". In the 17th century, the practice spread and composers wanted to leave indications on the score related to the speed at which they wanted their music performed. These indications have been of various types depending on the moments and musical traditions, but there is a moment of important change when the metronome is invented in 1812, patented by Johann Maelzel in 1816.

Regarding the graphic representation of these indications, both textual and metronomic, they are often located immediately above the staff when it is a score with a single staff, or the upper staff when it is a piece with multiple staves.

Before the invention of the metronome

In classical music, until the invention of the metronome, it was customary to describe the tempo of a piece by one or more words, usually adjectives that described the speed of the piece of music and its performance such as andante, allegro etc Most of these words are Italian during the 17th century and especially the 18th, regardless of the author's nationality and the place where this music was produced. This was so because many of the most important composers of the 17th century were Italian, and this period was when indications of tempo were widely used and codified for the first time. Its use became progressively widespread throughout Europe throughout the XVIII century, especially that of the most common words (adagio, andante, allegro and presto).

Sometimes these expressions also provided information about the character or expression that had to be given to the music. This blurs the traditional distinction between tempo and character indicators. For example, andante (walker in Italian) gives a certain sensation of movement, however allegro is indicative of speed but above all of character. Another example is the case of presto and allegro, both of which indicate fast execution, where presto is faster. For its part, allegro also connotes joy due to its original meaning in Italian; while presto indicates speed as such. In the expression Allegro agitato that appears in the last movement of George Gershwin's Piano Concerto in F, it is an indication of tempo that is undoubtedly faster than a usual allegro; but also an indication of character by the adjective agitato ("agitated").

Especially in the second half of the XVIII century, music preserved in music boxes and musical clocks, and in general in all kinds of gadgets capable of reproducing music mechanically, they are a tool of the first importance to know the real speeds at which the music was played. After the invention of the metronome, they continued to be used and towards the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the XX, with the emergence of nationalisms, tended to use their corresponding translations into the languages of the authors who used them.

After the invention of the metronome

The invention of the metronome, with which one could both set the speed to a certain number of beats per minute, and hear these beats while playing music, allowed much greater accuracy than had been possible before. From that moment on, the author could express which figure (usually black, but also the white one or the eighth note, or the dotted quarter note depending on the type of compass) was the one that was taken as the unit of measure, which one was the equivalent at a press. At the same time, an adaptation of the previous system -which did not disappear- to the new one was carried out, establishing for example that an andante corresponded to between 60 and 80 beats per minute. Thus, each of the textual indications in Italian corresponds to a range of numerical metronome indications.

Mathematical tempo markings of this kind became increasingly popular during the first half of the 19th century, once the metronome was invented by Johann Nepomuk Mälzel although early metronomes were somewhat inconsistent. The first composer to use the metronome was Beethoven and in 1817 he published metronomic indications for his (then) eight symphonies. Some of these marks are today the subject of controversy, such as those of his Piano Sonata "Hammerklavier" and his 9th symphony, as to many he appears to be almost impossibly fast. The same is true of many of Robert Schumann's works. As an alternative to metronome markings, some composers of the 20th century like Béla Bartók and John Cage, they would provide the total playing time of a work, from which the relevant tempo could be roughly deduced.

With the advent of modern electronic music, beats per minute became a highly accurate measure. Also, music sequencers use this system of ppm to indicate the tempo. Tempo is as essential in contemporary music as it is in classical. In electronic dance music, knowing the exact ppm of a song is essential for DJs for the purposes of beatmatching (rhythm synchronization). In general, throughout the last centuries the tempo has been indicated with an increasing degree of precision by the creators of music. This does not prevent various elements, among which we can count the technical abilities of the interpreter, the size of the group, the acoustics of the room, etc. may lead to apply tempo criteria that do not entirely coincide with those proposed by the author.

The tempo beyond speed

There is some relationship between the tempo markings and the time signatures that are used, a holdover from medieval notation. Thus, a time signature of 3/2 usually designates a slower tempo than a 3/4; while 3/8 takes us to a faster tempo. A similar relationship is also established between the measures 4/4 and 2/2 (alla breve). In such a way that the measure also becomes a way of providing information about the tempo.

Epstein has pointed out that tempo, however, is not only the result of establishing how many tenths of a second a quarter note lasts, but that it is the result of complex interactions between many elements that come together in a musical work such as thematic work, the rhythms, articulation, breathing, harmonic progressions, tonal movement, contrapuntal activity, etc. Tempo is a reduction of all this globality to a concept of speed, when in reality it is much more a concept of movement in the broadest sense of the word. Hence, finding the correct tempo, the most suitable one, is one of the subtlest and most difficult tasks that a performer faces.

The tempo understood

In some cases (quite often until the end of the Baroque), the conventions governing musical composition were so rigid that it was not necessary to specify any tempo. For example, the first movement of Bach's Brandenburg Concerto No. 3 contains no tempo or character indications. When providing the names of the movements, the publishers of the recordings resort to ad hoc measures such as marking the Brandenburg movement as Allegro, (Allegro), (No indication) and so on.

In Renaissance music almost all music was understood to flow in a rhythm defined by the tactus, roughly like the rhythm of the human heartbeat. The figure corresponds to the tactus indicated by the mensural compass.

Often a certain musical form or genre implies its own tempo, so no more detailed explanations are needed in the score. Consequently, musicians expect a minuet to be played at a rather stately pace, slower than a Viennese waltz; a perpetuum mobile which is quite fast, and so on. Musical genres can be used to imply certain tempos, which is why Ludwig van Beethoven wrote "In Tempo d'un Menuetto" on the first movement of his Piano Sonata op. 54, even though that movement is not a minuet. Popular music charts use terms like "bossa nova", "ballad" and "Latin rock" pretty much the same way.

It is important to keep in mind when interpreting these words that the tempos have varied throughout the different stages of history and even in different places, but sometimes even the order of the words has changed. terms. Thus, a current largo is slower than an adagio, however in the Baroque period it was faster.

Indication by expressions

By historical convention, dating back centuries, most of the expressions used to indicate tempo in sheet music are in Italian.

Indicators of a certain tempo

The following lists various expressions that refer to a certain tempo, ordered from slower to faster speed.

- Larghissimo: extremely slow (less than 20 ppm); rarely used.

- Length: very slow (20 ppm).

- Slow moderation: (20 - 40ppm).

- Slow: slow (40 - 60 ppm).

- Grave: slow and solemn (≈40 ppm).

- Larghetto: slower or less (60 - 66 ppm)

- Adagio: slow and majestic (66 - 76 ppm); for Clementi, the longest movement was not the longest but the adagio.

- Adagietto: a little slower than the adagio (70 - 80 ppm); unused.

- Tramp.: quiet.

- Tranquilla.

- Afettuoso: (72 ppm).

- Walking: at the pace, quiet, a little vivacious (76 - 108 ppm).

- Andante moderato: with a little more speed than the walker (92 - 112 ppm).

- Andantino: more alive than the moderate walker; however, for some it means less alive than the walker.

- Espressivo

- Moderate: moderate (80 - 108 ppm).

- Allegretto grazioso.

- Allegretto: a bit animated; however, in some pieces it is played as allegro and others as a walker.

- Allegro moderato.

- Allegro: animated and fast (110 - 168 ppm).

- Vivace: vivacious.

- Alive: quick and lively.

- Allegrissimo: faster than the allegroUnused.

- Presto: very fast (168 - 200 ppm).

- Vivacissimo: faster than the aliveUnused.

- Vivacissimo: Faster than the Vivacissimo.

- Prestissimo: very fast (more than 200 ppm).

- Allegro prestissimo with fuoco: extremely fast (more than 240 ppm).

INDICATORS OF A TEMPO CHANGE

- Gradual increase in speed

- Stretto

- Stringendo

- Accelerating

- Affrettando

- Gradually slow down

- Rallenta

- Ritardando

- Ritenuto

- At the will of the interpreter

- A piacere

- A capriccio

- Ad libitum

- Rubato

- Returning to the original tempo

- A tempo

- Season 1

Other expressions used

- Sustained: holding and neglecting a little time.

- Morendo: go off the sound and ralling.

- Non troppo: not too much. (Example: Allegro ma non troppo vivace)

- With motorcycle: with movement.

- Molto: a lot.

- Little by little.

- Tempo di...: it is accompanied by the name of some type of composition to indicate that it must be touched as it is common in that genre. For example, "Tempo di Valzer" indicates that the speed must match the one used in most of the waltzes.

- Quasi: almost.

- Assai: both, very, enough or enough.

- The temp stew: at the same speed.

- Monkey season: at a consistent speed.

Metronomic indication

Almost always, the Italian word that designates the tempo is accompanied by the metronomic indication.

This is an expression that indicates the exact speed most suitable for a piece of music indicating how many figures of a certain value should be played in a minute (or compass). Thus, the indication ![]() = 60 it translates into running a piece at such speed that sixty blacks will fit in a minute.

In practice, to achieve this accuracy a device called metronome. The metronomic indication is used to homogenize the determined speed as otherwise there could be different interpretations of how to play, for example, a allegro. However, it is often placed by the reviewer, so that occasionally it does not coincide with the interpretation of the original author. This unit is usually used to measure tempo in music as well as heart rate.

= 60 it translates into running a piece at such speed that sixty blacks will fit in a minute.

In practice, to achieve this accuracy a device called metronome. The metronomic indication is used to homogenize the determined speed as otherwise there could be different interpretations of how to play, for example, a allegro. However, it is often placed by the reviewer, so that occasionally it does not coincide with the interpretation of the original author. This unit is usually used to measure tempo in music as well as heart rate.

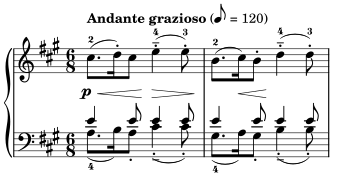

The beats per minute indication of a piece of music is conventionally represented in sheet music as a metronome indication, like the one illustrated in the image to the right. This indicates that there should be 120 quarter note pulses per minute.

- In the simple or binary subdivision societies, in which each of its pulses or times can be subdivided into halves, the tempo is usually shown according to the musical figure in the denominator of the compass. Thus, for example in a 4/4 beat would show a black one, while a 2/2 would show a white one.

- In the composite or tender subdivision societies, in which each of its pulses or times can be subdivided into thirds, so a figure with a pointer is used. The most common composite compases are 6/8, 9/8 and 12/8. For example, in the 6/8 compass there are six corshes per compass, so two blacks with a tip will be used to indicate each ppm in each compass.

Exotic times and in particular slow measures can indicate their tempo in bpm by other musical figures. The ppm indication became common terminology in disco music due to its usefulness to DJs and continues to be important in the same genre and other dance music.

Contenido relacionado

Within Temptation

Disney (disambiguation)

Bushidō