Tecumseh

Tecumseh (March 1768 – October 5, 1813), also known as Tecumtha or Tekamthi, was a native leader, both of the Shawnee Indian people of North America as a great confederation that opposed the United States of North America during the so-called Tecumseh War (or Tecumseh's Rebellion) and the Anglo-American War of 1812. He grew up in the territories that, the On March 1, 1803, they became the state of Ohio, the 17th state to enter the Union.

During his childhood and youth, the United States War of Independence (or American Revolution) and the Northwest Indian War took place, conflicts during which Tecumseh and his people were constantly exposed to numerous warfare and acts of arms.

Tecumseh was one of the greatest indigenous figures in North American history. With a noble attitude and behavior according to indigenous criteria, alien to Western education. To many he was a statesman, a warrior and a patriot (or the equivalent of him from the point of view of the Western tradition). Tradition presents him as a learned and wise man, respected and admired, even among his white enemies, for his integrity and humanity (so much so that his memory is honored today in both the United States and Canada, from indigenous and white alike).

In the Spanish-speaking world, due to his location in space and time, there is little literature on him and he is less well known than other indigenous leaders associated with Old West myths and realities, such as the Oglala Sioux, Makhpyia-luta (Red Cloud or Red Cloud) and Tasunka witko (Crazy Horse or Crazy Horse), the Sioux hunkpapa, Tatanka Iyotake (Sitting Bull, or Sitting Bull) and the Apaches of the Chiricahua tribe, Mangas Coloradas, Cochise and Gerónimo, whose images have been widely used in the westerns and western novels (to the point of making many believe that they are cartoon characters). However, in the English-speaking world there are numerous references to the renowned indigenous caudillo whose life and work are also the subject of historians, novelists, and screenwriters for film and theater.

A Shawnee by birth, he considered himself Indian first and fought to the end of his existence to give the indigenous peoples of the Great Lakes region the Midwest (or Midwest) and, in general, the east of the Mississippi River, a national consciousness beyond the tribal. His hope was always to unite them in defense of a motherland (homeland, own land with which to identify) in the that they might abide under their own laws and leadership. The fact that he ultimately failed meant much more than seeing Indiana become a white state instead of an Indian one. It meant that all the tribes were reduced to meager resources and ranged separately, as they had been before the original white man's invasion. More importantly, it implied, forever, the end of any possibility that a free Indian state could be created in that part of the territory that, finally, was dominated by purchase or arms by the United States.

The early years

"No portrait of him was made during his life. no account of his words remained as testimony. Looking back at the movement that led seemed to be doomed to failure from the beginning. And yet, in the course of his impressively brief and metheorical career, he rose to become one of the greatest Native American leaders of all time. And in one of the most talented, anticipator of the future, venerated and inspiring, capable of forging the coals of the roaring vision of his younger brother, an extraordinary coalition, and of orchestrating the most ambitious pan-indigenous movement of resistance ever organized on the American continent."

Mythical-historical background

The early life of Tecumseh ("Shooting Star", "Panther Crossing the Sky" or "Flying Arrow") is wrapped up in what John Sugden, one of his biographers, calls "the twilight world between myth and history"; his uncertain date of birth is tentatively placed as 9 March 1768, perhaps outside Chillicothe, in what for the first decade of the century XXI is Old Town, in Greene County, Ohio, somewhat north of the contemporary city of Xenia, Ohio. His father was Pucksinwah, a minor war chief, a member of the Kishpoko (“Dancing Tail” or “Panther”) branch of the Shawnee tribe. His mother's name was Methoataske, or Methotasa: a woman belonging to the Pekowi branch of the tribe and the second wife of Pucksinwah (as Shawnee bloodlines were recorded patrilineally, Tecumseh was Kispoko).

About the birth of Tecumseh, the American historian, historical novelist and naturalist Allan W. Eckert points out in his book Gateway to empire, that the little son of Methoataske with the Shawnee war chief, Pucksinwah, he was christened 'Tecumseh' or 'Passing Panther,' "because on the night of his birth a great comet, which in Shawnee mythology is seen as a panther, had scorched its way through the heavens." Now, by the time his parents were united, the tribe into which Tecumseh would be born was living near what later became the city of Tuscaloosa, Alabama.). At that time, the Shawnees (or 'shaawanwaki', 'shaawanooki' or 'shaawanowi lenaweeki'), considered by other indigenous tribes in the Algonquin group of peoples to be their southernmost tribe of (the early etymology of their name leads to Algonquian, 'shawano' equivalent to 'south'), had been displaced from their ancestral lands in the Ohio River valley by the powerful Iroquois Confederacy, during some episodes that occurred between 1670 and 1700, within the framework of the so-called Beaver Wars.

Around 1759, the Shawnee Pekowi decided to return north to their old homelands in the Ohio region, which had been depopulated at the end of the Beaver Wars. Not wanting to force his wife to choose between him and his family, Chief Pucksinwah decided to travel with the party. The Pekowi founded a settlement at Chillicothe, where Tecumseh was possibly born. Shortly after his birth, the family moved again to the village of Scioto, also on the banks of the Ohio. Tecumseh's father, like many other indigenous chiefs in the region, was involved in the French-Indian War (between 1754 and 1763) and, later, in the so-called Lord Dumnore's War or Dunmore War. Precisely in the middle of this contest, the seasoned Pucksinwah found his death in combat, in the Battle of Point Pleasant or Battle of Kanawha, which took place on Monday, October 10, 1774.

In view of the subsequent fear of the defeat of the natives by British colonial forces in Virginia, and in view of the attacks by the white or 'Shemanese' settlers that were accentuated by the outbreak of the United States War of Independence in 1775, good Some Shawnee people—including Tecumseh's mother, Methoataske—fled the region in 1779, moving west, first to settle in the Indiana Territory, then the Illinois lands, and finally to the Missouri counties.. Tecumseh, then eleven years old, would remain in the Ohio territories with the Shawnee who decided to resist; there he would be raised by his older brother, Chiksika, and his sister, Tecumapese.

Son of nomadism and conflict

At least five times between 1774 and 1782, the villages in which Tecumseh temporarily resided were attacked, first by troops from the British colonies and then by American armies, when the Shawnee allied with the British during the American Revolution. After the death of Tecumseh's father (Pucksinwah), the family moved to Chillicothe, the nearby village of Chief Blackfish (in Shawnee Cottawamago or Mkahdaywaymayqua), where she was adopted by him. Said town was also destroyed in 1779 by the “Shemanese” militia from Virginia (the Shawnee called the Virginians Shemanese, or “long knives” —in reference to their swords— and this denomination ended up extending it to all Americans), in retaliation for an attack by Chief Blackfish's warriors on the town of Boonesborough, founded by pioneer Daniel Boone and inhabited at the time by him and his people. Tecumseh's family (including himself) escaped and moved to another nearby village of the Kispoko clan of the Shawnee, but their new home was likewise destroyed the following year by US forces, this time under the command of General George Rogers Clark. The family then moved a third time to the Sanding Stone village. That village was again attacked by Clark and his troops in November 1852, forcing the entire group to migrate to a new settlement near the modern town of Bellefontaine, Ohio.

Violence continued unabated on the internal border of the United States after the American Revolution, in the conflict known as the Northwest Indian War. In the course of it, a large tribal confederation, called the Wabash Confederacy, which included virtually all the great tribes of the Ohio and Illinois counties, united to repel American settlers from the region. between the Indian confederation and the Americans continued, Tecumseh became a young combatant who took part in the conflict fighting under the orders and side of his older brother Chiksika (Cheeseekua). In this historic process, Tecumseh gained experience in combat, including the battle of the Fallen Trees or Fallen Timbers, on Wednesday, August 20, 1794, in which he witnessed the deblace of his people, and which culminated in the war in favor of the victorious Americans.

Tecumseh's war against the United States

"Tecumseh was the most extraordinary Indian who has ever appeared in history. It was by birth a shawnee but it could have been a great man at any time or nation. Regardless of the most consummated courage and skill as a warrior, and of all the characteristic sagacity of his race, he was invested by nature with all the mental attributes necessary for the great political combinations. His sharp understanding, very early in life, informed him that his countrymen had lost their importance; that they were gradually yielding to the whites, who were acquiring an impositive influence on them. Instigated by these considerations and, perhaps, by its natural ferocity and bonds with war, it became a determined enemy of the whites, imbued with an invincible determination (which only yielded with his life) to recover for his country the proud independence it meant was lost."

Initial tensions

Towards the end of the 1780s Tecumseh, together with his brother Elskwatawa or Tenskwatawa, who was called "the prophet", created an alliance of Native peoples against the expansion of American settlers into the Great Lakes Territories, the Northern Midwest, and the Ohio River Valley. The alliance underwent some changes over time, but it was made up of several important Indian towns.

In September 1809, William Henry Harrison, governor of the newly formed Indiana Territory, negotiated the Treaty of Fort Wayne in which a delegation of Indians ceded 3 million acres (12,000 km²) of Native American land to United States government. The treaty negotiations were questionable since they did not have the support of then-US President James Madison, and involved what some historians have compared to bribery, consisting of offering large subsidies to the tribes and chiefs involved, and the prior distribution, among the indigenous participants, of copious amounts of liquor before the negotiations to "dispose the temperaments" to them.

Tecumseh's opposition to the noted Treaty of Fort Wayne marked the emergence of the Shawnee warrior as an outstanding leader and earned him the respect of several tribes. Although Tecumseh and his people, the Shawnees, had no claim to the land sold, the Indian chieftain was alarmed by the massive sale, since many of the followers who accompanied him in his capital, Prophetstown ("Prophet's Town"), belonged to to the Piankeshaw, Kikapú and Wea tribes, which were habitual inhabitants of the fraudulently negotiated land. As an argument, Tecumseh revived an idea espoused in earlier years by Shawnee leader Blue Jacket and Mohawk leader Joseph Brant that Indian land was the common property of all tribes and no fraction of it could be sold. without the consent of all, or only by decision of a few.

Not ready to directly confront the United States, Tecumseh's adversaries were initially the indigenous leaders who had signed the treaty. An impressive orator, Tecumseh began to travel widely urging warriors to abandon white-friendly chiefs to join him in resisting the treaty. Tecumseh insisted that the Fort Wayne treaty had been illegal; he petitioned Harrison to annul it, and warned the Americans that they should not attempt to settle on the land thus negotiated. Tradition evokes Tecumseh by saying: “No tribe has the right to sell [land], not even to another, much less to foreigners... Selling a country? Why not also sell the air, the clouds and the great sea with the land? Did not the Great Spirit make them for the use of all his children” and “…the only way to stop this iniquity [loss of land] is, for the red men, unite and claim a common and equal right to the land, as it was in the beginning, and should be now, so that it may never be divided.”

Confrontations: The Indian Grand Chief versus the Governor

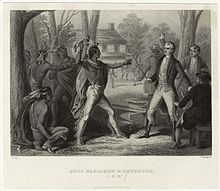

In August 1810 Tecumseh brought a party of four hundred armed and war-painted warriors from Prophetstown to confront Harrison at his Grouseland mansion in Vincennes, Indiana. The appearance of the Indian braves alarmed the locals, and the situation turned dangerous when Harrison rejected Tecumseh's demands, arguing that the tribes could have individual relations with the United States, and that Tecumseh's interference was considered meddling by the tribes. of the area. In response, Tecumseh launched a fiery rebuttal against Harrison:

(Governor William Harrison), You have the freedom to return to your own country... you want to prevent the Indians from doing what we want, joining and considering their lands a common property for all... You will never see an Indian effort to make white people do that...

Thereupon Tecumseh began to incite his warriors to kill Harrison, who defended himself by drawing his sword. Immediately, the small garrison defending the town of Vincennes reacted to protect Harrison. At this point, the Potawatomi chief, Winnemac —who professed friendship towards the Americans— intervened to counter Tecumseh's arguments against the group he led, and asked the warriors to leave in peace, which they reluctantly did. As they left, Tecumseh warned Harrison that unless the Treaty was revoked, he and his people would ally themselves with the British (whose domains of Canada were nearby and who were then preparing for war against the United States).

Some time later, while the hostilities continued, in March 1811 a great comet appeared in the sky, which was taken advantage of by the Shawnee leader Tecumseh, whose name, remember, means “shooting star”, to tell the Creeks, whose southern lands he had traveled to seek support in his planned campaign against the Americans, that the comet signaled that the time to fight had come, all the warriors that made up Tecumseh's Confederacy and their sympathizers took the matter as an omen of good luck. luck. By the way, some people who were concerned a few years after the events such as Thomas Loraine McKenney, an American official who served as Superintendent of Indian Commerce between 1816 and 1822, report that Tecumseh had indicated that he would prove to the clans of the Creek tribe that the Great Spirit had sent it, giving them a 'sign'.

In early 1811, Tecumseh met Harrison again at the Grouseland mansion in Vincennes, having been summoned there as a result of the murder of settlers on the frontier. Tecumseh told Harrison that the Shawnees and their Native American brethren wished to remain at peace with the United States but that these differences had to be resolved. The encounter was probably a maneuver by the Indian chief to gain time while he strengthened his confederation. So much so that this meeting convinced Harrison that hostilities were imminent. It would be after that episode that Tecumseh would travel south, with the mission of recruiting allies among the powerful Five Civilized Tribes of southeastern North America. Most of the chiefs of those Amerindian nations, by that time divided, like most of the Indian world, between pro and anti-Americans rejected his appeals, but a faction among the Creeks that would later come to be known as the Red Sticks (or ' red sticks'), would answer his call to arms, which would later lead to the Creek War of 1813.

Of the harangues that Tecumseh then addressed to the numerous assemblies of Indians with whom he met, there is one of which different versions circulate (attributing it in some cases to his brother, the prophet Lalawethika, later called Tenskwatawa):

"Listen, my people. The past speaks for itself. Where are the pequots today? Where are the narragansett, the powhatan, littlenokets, and other powerful tribes of our people? They have vanished at the greed and oppression of white man, like snow in the summer sun.... Look wide, about your once beautiful country and what do you see now? Nothing but the ravages of the face-to-page destroyers. That's how it's gonna be with you guys, chickasaw, choctaw. The annihilation of our race is imminent unless we join in a cause against the common enemy".

The Battle of Tippecanoe, Before, During and After

Tecumseh had his capital, called Prophetstown, a short distance from the current city of Lafayette, in the state of Indiana. In 1811 he left his brother in command of the alliance and traveled south to meet with other Indian nations that he wanted to join the alliance. Among these were peoples as powerful as the Creeks and the Cherokee. During his absence, his command post was attacked by American troops. A hard battle took place, which ended with the defeat of the Indians, and with it, the dream of a broad and strong alliance of the native peoples.

While Tecumseh was in the south seeking to assemble Indian forces to confront the whites, Governor Harrison moved up the Wabash River from Vincennes with more than a thousand men, in a preemptive expedition to intimidate the prophet Tenskwatawa and his followers with the intent of force them to make peace. On Wednesday, November 6, 1811, Harrison's army arrived on the outskirts of Prophetstown. The Prophet sent a messenger to parley with Harrison, the mission of this emissary was to request the commander-in-chief of the long knives (Harrison), to arrange a meeting the next day. Harrison camped with his army on a nearby hill; There during the early morning hours of Thursday, November 7, 1811, the warriors of the Indian Confederacy launched a sneak attack on the Americans' camp. Despite everything, the Americans maintained their positions, and the Indians withdrew from the village after the battle. The victorious Americans then took the town of Prophetstown, destroyed the surrounding crops and burned it down.

The Battle of Tippecanoe thus constituted a severe blow for Tenskwatawa, who lost in one fell swoop both the prestige he had gained among the indigenous tribes and the trust of his brother. Despite this, and although it was a significant setback, Tecumseh secretly began to rebuild his alliance once he returned to the scene. Shortly thereafter the Americans went to the War of 1812 against the British, and Tecumseh's War would become part of that larger conflict.

One month after Tippecanoe, on Wednesday, December 11, 1811, the violent New Madrid earthquake struck, shaking the South and Midwest. Although the interpretation of the natural phenomenon varied from tribe to tribe, all the Reds came to a universally accepted consensus that the most powerful earthquake experienced in the continental United States (i.e., excluding Alaska and Hawaii) in historical times had to have meant something. For many tribes it meant that Tecumseh and the Prophet had to be supported.

Meanwhile, tensions grew between the Americans and Great Britain, leading to war between the two in 1812. Tecumseh raised a troop of natives, enlisting them in the British army as an ally. In the early morning hours of August 16, Tecumseh's warriors crossed the Detroit River in what would be the first action of the battle that ended the siege of Detroit and the subsequent American surrender. He was killed during a battle in Ontario.

Contenido relacionado

5

1890s

2nd century BC c.