Tartessian language

The term Tartesian language has three meanings:

- The language of the city of Tartessos;

- The language corresponding to the inhabitants of the orientalizing culture of Lower Guadalquivir between the eighth and sixth centuries BC (which is archeologically called tartesia);

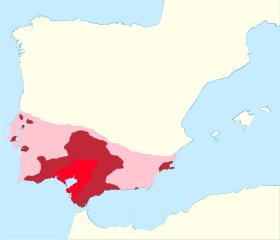

- The language corresponding to a setentna of brief inscriptions that have been found mainly in southern Portugal (Algarve and Baixo Alentejo), while some have also been found in the middle Guadiana (in Extremadura) and a few in the Lower Guadalquivir. Since in the area itself tartesia its documentation is exiguous, it has been discussed whether this writing corresponds effectively to the late language or whether it is a peripheral language to the late.

That is why when the language of these steles is called " Tartesio " O " Tartessic " Keep in mind that this name is still a hypothesis: that it would be the language of the ancient kingdom of Tartessos. Many historians have opted for a different denomination for the language of these steles: Sudusitana (Schmoll, Rodríguez Ramos, and until recent It would be between Huelva and the Guadalquivir Valley). On the other hand, the denomination Sudlusitana has the inconvenience of lending itself to confusion implying the idea of a relationship with the Lusitanian language. Other names would be bastulo-turdetana (Gómez-Moreno), of the southwest (motorcycle maluquer), of the carve (of hoz) and more carefully Cynetic or language of the cynetes or conios (koch).

Turdetans of Roman era are considered the heirs of the Tartessic culture, and possibly the term Turd-Ethane is a late variant of Tart -ssio. Estrabón mentions them as " the most cults of the Iberians and who have writing and writings of about 6000 years ".

""They are reputed as the most wise (σοφεατοι) among all Iberians; they possess grammar, and books with ancient memoirs (παλαι.ς μνς μις), poems and metric laws of six thousand years old, as they say. The other Iberians also have grammar, though not in the same way, nor speak the same language..." (Str. III, I, 6)

Non-epigraphic evidence of the language of the Tartessos region

In addition to the testimony of the so-called Tartessian inscriptions, there is additional information derived from the proper names mentioned in mainly Greco-Latin texts. Thus we have anthroponyms explicitly related to the kingdom of Tartessos and indigenous anthroponyms known in the region in Roman times.

Very little is known about the anthroponyms clearly linked to the kingdom of Tartessos, although some interpretation is interesting. It has been suggested that the name of King Arganthonios, whose kingdom is said to be opulent in silver, coincides with the Celtic term for silver *argantom, so that it would be, literally, he of silver; it has also been suggested that the mythical king Gargoris, could be understood in Gallic Celtic as a *gargo-rix "fierce king" / "terrible king". These interpretations would coincide with the line of those who consider that the language of the Tartessian stelae would be Celtic. On the other hand, the presence of the typical suffix in pre-Greek Aegean terms -essos has been pointed out from the name Tartessos itself. However, as Jürgen Untermann has pointed out, it cannot be ruled out that different indigenous names have been distorted by the Greeks, according to sequences that were familiar to them.

From the testimony of the Andalusian area from Roman times, Untermann has shown that the Iberian Peninsula is divided into three regions according to the terms used for the names of cities: some are the Iberians in iltiŕ- (basically in the Mediterranean area), others are the Celts in -briga, while in the Bajo Guadalquivir sector some place names predominate that can be found from Lisbon to Malaga and that present the formant -ipa/-ipo/-ippo, as we see in Oliss-ippo (Lisbon) and in others such as Baes-ippo, Il-ipa, Ipo-lca and others with the suffix -oba/-uba, as in On-oba (Huelva), Cord-uba (Córdoba), Ipo-noba, Maen-oba, Ob-ulco or Osson-oba. These place names are an index of an undetermined linguistic stratum, and there are no indications that it is the same language used in the southwest stelae or cynetas or that it is the same natural language used in the cities of the territory of Tartessos, although its Geographical dispersion allows us to consider this possibility, either as a Tartessian language or as a Turdetan language.

History

It is not yet known when the Tartessian language arose or when it reached the Southwest of the peninsula. In the event that the language of the epigraphic stelae from the Southwest (cynetic or conian stelae) is shown to be the same as that used by the Tartessians, it should be noted that this only appears on a series of stelae whose dating is unclear, but which would correspond, at least, to the 7th/6th to the 5th centuries B.C. c.; while there is discrepancy as to whether the script/language of the Salacia mint (Alcácer do Sal, Portugal) from around 200 B.C. C. actually corresponds to the language of the stelae, although the transcription of the mint allows us to recognize a significant ending in "-ipon".

Nor is it known exactly when the Tartessian language would stop being spoken, but it can be assumed that, as in the rest of the southern peninsula, the acculturation caused by the Romans would be relatively rapid when the administrative reorganization into provinces and provinces took place. the Latin colonizations, after the military defeats of the previous hierarchies of power.

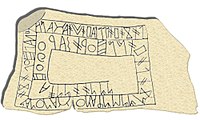

Writing

The writing of the steles is a very similar paleo -Hispanic writing, both because of the shape of the signs and for the value that the signs represent, to the southeast Iberian writing that expresses Iberian language. On the origin of the Paleohispanic writings there is no consensus: for some researchers its origin is direct and only linked to the Phoenician alphabet, while for others in its creation the Greek alphabet would also have influenced and even some signs taken from an indigenous local tradition.

With the exception of the Greco-Chérico alphabet, the rest of Paleo-Holy Scriptures share a distinctive typological characteristic: they present signs with syllabic value for the occlusive and signs with alphabetical value for the rest of consonants and vowels. From the point of view of the classification of writing systems they are not alphabets or syllabaries, but mixed writings that are normally identified as semi -barracks. The particularity of Tartesia writing is the systematic vocal redundancy of the syllabic signs, a phenomenon that in the other paleohispanic writings is residual. Some researchers consider this writing as a redundant semi -save, while others consider it a redundant alphabet. The phenomenon of the vocal redundancy of the syllabic signs was discovered by Ulrich Schmoll and allows us to classify most of the signs of this writing in syllabic, vocal and consonant. Even so, its decipherment cannot yet be closed, since there is no consensus among the different researchers who have made concrete proposals.

Example texts

- Fonte Velha (Bensafrim):

- lokoroboroniiraborotoroaaalteelokornanenaaa?iiśiinkoroloboroiiteerobaarebeeteSoon

- (Untermann 1997).

- Herdade da Abobada (Almodôvar)

- ir'ualkuusie::nakeentiimubaateerobaare they?aataaneatee

- (Untermann 1997).

The language of the wakes

The current state of semi -milla discipheration is provisional and unfinished. There are signs whose reading is not safe and texts almost never have separation between words. Therefore, an attempt for translation or even reading is very risky, although on most inscriptions (given its brief character, with a series of repeated words with respect to an apparent proper name always different) there is some unanimity about that They would be funerary inscriptions.

In the current state of knowledge, little can be said more than giving a generic vision from transcripts. 5 members are distinguished: " A ", " E ", " i ", " O " Y " U "; having noticed the presence of the diphthongs /ai /and /oi /. The use of the sign " U " in semiconsonatic function of /w /. As in Ibero, signs are distinguished for the three orders of oral velar, dental and lipstick occlusive; but it should be noted that although the transcription is done with the deaf " K ", " t " Y " P " They would not be indicative of whether they were deaf or sound; In the same way, although sometimes the lipstick is transcribed as " b ", it does not imply that it is sound and not deaf (note that " p

a

are &# 34; Y " Ba

are " are two different transcripts of the same letters tartesias. The consonants " l " Y " n &# 34;, as well as two " s " (perhaps one of them palatal) and two " r " (of unknown distinction); while the use of " m " only ante ".The most repeated terms are the ' Words ': " p

a

are " Y " naŕke

ent i </sa enii ", " naŕke

eii " o " naŕke

enai " (among others) and forms perhaps abbreviated (?) As " naŕk e e " O " Naŕke in ". It is interesting to indicate that, in an exceptional way, the first term presents variants with terminations similar to those of the second /Sup> ant i

i "; which is why it has been proposed that both were verbs. To a lesser extent, other elements such as " (pa a) t e

e ero ", " Iru " (for atermann an pronoun or an adverb), " pa

Anne " O " Uarp a an ", this term on which Correa has indicated that it could be an honorary title or magistracy that would indicate the rank of the deceased.of the alleged proper names, it has been indicated that they usually present characteristic finals (which could be typical suffixes of anthroponyms formation) as " -on ", " -ir " o " ea "; that can also go together in cases like " on-Ir " O " IR-EA ". Some possible anthroponyms would be: Aark u

uior, aip u uris, akor

olion, arpu

uiel, k kor </sa p

or ot

i

iea, śut u uiirea, t a alainon, t i Irtor

os, uarp or oiir or uursaar.It is not clear if the tongue was flexive or binder, although the apparent existence of suffixes has been pointed out, as already seen when dealing with the variants of the formula and those of anthroponyms, as well as others relatively frequent, such as & #34; -śe " O " -Ne ".

Relationship with other languages

Estrabón comments that:

(the Turks) have writing... Also the other Iberians have writing, but not the same, being also their different languages

Since 1966 there have been various attempts to identify the language of the Tartessian inscriptions, all of the attempts aimed at identifying it as an Indo-European language, but, as interesting as these attempts may be, they have not reached any definitive conclusion and, in fact, recently the opposite hypothesis has been proposed: that the available data advocates that it is a non-Indo-European language. Subtracting this pending discussion, its lack of relationship with the other neighboring languages does seem clear: neither with Iberian, nor with Basque, nor with Berber, nor with Phoenician.

Indo-European Hypotheses

Anatolian and Greek hypothesis

The pioneer of these studies was Stig Wikander and, although his proposals are hampered by the use of an obsolete transcription, his main proposal continues to be the subject of study: seeing in ke enii and keentii are two verb forms according to the Indo-European conjugation. The first form would follow the model of the conjugation -hi of the Anatolian languages in which, as in ancient Greek, an ending -i is the mark of the third singular person. While in the second, we could either have a third of the plural of the conjugation -hi (ending -nti) or a third of the singular of the conjugation -mi (ending -ti). Thus was born the Anatolian hypothesis, which suggested a relationship between the Anatolian peoples and Andalusia very much in line with the diffusionist reconstructions of Adolf Schulten (for whom Tartessos was an Etruscan colony, who in turn were of Aegean origin), of Gordon Childe and of Manuel Gómez-Moreno (for whom the Tartessian culture and more specifically its writing was related to the Minoan culture). Ideas all of them today surpassed.

Celtic Hypothesis

Later, Correa believed he found some indications that the language of the inscriptions could be Celtic. The Celtic theory is historically consistent, since the Greco-Latin sources expressly mention the presence of celtici in Baetica, even though its presence can be interpreted as a late arrival from the s. V BC (or even in the IIaC century) and do not seem to be related to Tartessian place names, but rather to place names in briga.

Correa identified some interesting interpretations of the Tartessian terms. Thus, in uarpaan we would have the Indo-European prefix uper with the drop of the /p/ typical of Celtic languages and the term would come to mean supreme, in the name aipuuris we would have an Indo-European aikwo-rex ('the just king') with a phonetic evolution identical to that of Gaul; at startup lokoopooniirapoo should read Logo-bo Niira-bo where we would have a mention of the Celtic god Lug and ner ('man', 'warrior'), declined according to a plural dative -bo (Celtiberian -bos, Latin -bus) which would indicate the deities to which the inscription would be dedicated.

However, where Correa has placed more emphasis has been on the equating of some of the anthroponyms that head the Tartessian inscriptions with well-known Celtic names, such as Acco, Alburus, Ambatus and others.

With all these precedents, Untermann has finally tried to carry out a synthesis in which his main contribution beyond Correa's proposals has been the attempt to parallelize the Indo-European morphology with the sequences found in the stelae. Thus follows the consideration of some verbs with singular in -i and plural in -nti (with verbs naŕkee- and baare)y suggests that the endings in -a and -ea were feminine nominatives, in -on a singular Accusative or a neuter Nominative, the endings in -r would be forms in -r-os as in Latin (faber < *fabrs < *fabros), and -kun a genitive plural of a family name in -k- like the Celtiberians.

All in all, the Celtic hypothesis is experiencing a certain decline or disenchantment. Correa himself has considered his results inconclusive and has appreciated the lack of the typical Indo-European inflection in the inscriptions, suggesting that although the anthroponyms appear to be Celtic, the language would not be (there would have been an entry of Celtic people into a non-Celtic environment).. For his part, Rodríguez Ramos, after having shown himself to be in favor of the Indo-European interpretation, is critical of all its points. At the morphological level, he considers that the morphological similarities are occasional, that they cannot explain all the variants, giving minority or exceptional variants as a rule. But he also considers that the vocalism of the anthroponyms is incompatible with Celtic phonetics and that, as a whole, the language of the stelae could not be related to any known Indo-European linguistic family, considering its Indo-Europeanness as not impossible, but improbable.

In recent years the thesis of the professor at the University of Wales, John T. Koch, who sees in the language of the southwest or Tartessian the oldest documented Celtic language, which would date back to the century VIII a. C. has gained a lot of strength. Despite this, there is still no complete scientific consensus on the subject.

Geographic extent

The texts have been found in the Algarve and Lower Alentejo, in southern Portugal and in the middle courses of the Guadalquivir and Guadiana.

Contenido relacionado

Morphosyntactic alignment

Creation myth

Ϻ