Tang dynasty

La dynasty Tang (in Chinese simplified and traditional, ; pinyin, TangoWade-Giles, T'ang Ch'ao; ![]() thh derived (?·i)) was an imperial dynasty of China that ruled from 618 to 907, with an interregno between 690 and 705. It was preceded by the Sui dynasty and followed by the period of the Five Dynasties and the Ten Kingdoms in Chinese history. Historians generally consider Tang as a climax of Chinese civilization and a golden era of cosmopolitan culture. Tang territory, acquired through the military campaigns of its first rulers, rivaled the Han dynasty. The capital Tang in Chang'an (current Xi'an) was the most populous city in the world in its day.

thh derived (?·i)) was an imperial dynasty of China that ruled from 618 to 907, with an interregno between 690 and 705. It was preceded by the Sui dynasty and followed by the period of the Five Dynasties and the Ten Kingdoms in Chinese history. Historians generally consider Tang as a climax of Chinese civilization and a golden era of cosmopolitan culture. Tang territory, acquired through the military campaigns of its first rulers, rivaled the Han dynasty. The capital Tang in Chang'an (current Xi'an) was the most populous city in the world in its day.

The Lǐ (李) family founded the dynasty, seizing power during the decline and collapse of the Sui Empire. The dynasty was interrupted for 15 years when Empress Wu Zetian seized the throne, proclaimed the Wu Zhou dynasty, and became the sole reign of the legitimate Chinese empress. In two censuses from the 7th and 8th centuries, Tang records estimated the population per number of registered households at approximately 50 million. However, even as the central government was collapsing and unable to compile an accurate census of the population in the 9th century, the population is estimated to have grown by then to about 80 million. With its large Based on population, the dynasty was able to muster professional and conscripted armies of hundreds of thousands of troops to compete with nomadic powers for dominance in Inner Asia and the lucrative trade routes along the Silk Road. Various kingdoms and states paid homage to the Tang court, while the Tang also conquered or subjugated various regions that it controlled indirectly through a protectorate system. In addition to political hegemony, the Tang also exerted a powerful cultural influence over neighboring East Asian states such as Japan and Korea.

The Tang dynasty was largely a period of progress and stability in the first half of the dynasty's rule, until the devastating An Lushan Rebellion (755–763) and the decline of central authority in the second half of the dinasty. Like the Sui dynasty before it, the Tang dynasty maintained a civil service system by recruiting academic officials through standardized examinations and recommendations for office. The rise of regional military governors known as jiedushi during the IX century undermined this civil order.

Chinese culture flourished and matured further during the Tang era. It is traditionally considered the greatest era of Chinese poetry. Two of China's most famous poets, Li Bai and Du Fu, belonged to this age, as did many famous painters such as Han Gan, Zhang Xuan, and Zhou Fang. Scholars of this period compiled a rich variety of historical literature, as well as encyclopedias and geographical works. Emperor Tang Taizong's adoption of the title Khan of Heaven, in addition to his emperor title, was the first "simultaneous reign" for the Emperor. from East Asia.

Many notable innovations occurred under the Tang, including the development of woodblock printing. Buddhism became a major influence on Chinese culture, with native Chinese sects gaining prominence. However, in the 840s, Emperor Wuzong of Tang enacted policies to persecute Buddhism, which subsequently waned its influence. The dynasty and the central government had fallen into decline in the second half of the ninth century; land rebellions led to atrocities such as the Guangzhou massacre of 878-879. The dynasty was overthrown in 907 after decades of crisis.

History

Establishment

The Li family belonged to the northwestern military aristocracy that prevailed during the Sui Dynasty and claimed paternal descent from the Taoist founder, Laozi (whose personal name was Li Dan or Li Er), the Han Dynasty general Li Guang and the Western Liang ruler Li Gao. This family was known as the Longxi Li lineage (Li lineage; 隴西李氏), which includes the Tang poet Li Bai. The Tang emperors also had maternal Xianbei ancestry, from Emperor Gaozu of Tang's mother, Duchess Dugu.

Li Yuan was the Duke of Tang and governor of Taiyuan, present-day Shanxi, during the collapse of the Sui dynasty, which was caused in part by the Sui's failure to conquer the northern part of the Korean peninsula during the Goguryeo War -Sui. He had military prestige and experience, and was a first cousin of Emperor Yang of Sui (his mothers were sisters). Li Yuan rose in rebellion in 617, along with his son and equally militant daughter, Princess Pingyang. (died 623), who raised and led her own troops. In winter 617, Li Yuan occupied Chang'an, relegated Emperor Yang to the position of Taishang Huang, or retired emperor, and acted as regent for the puppet child emperor Yang You. Following the assassination of Emperor Yang by the general Yuwen Huaji on June 18, 618, Li Yuan declared himself emperor of a new dynasty, the Tang.

Li Yuan, known as Emperor Gaozu of Tang, ruled until 626, when he was deposed by his son Li Shimin, the Prince of Qin. Li Shimin had commanded troops since the age of 18, was proficient with bow and arrow, sword, and spear, and was known for his effective cavalry charges. Fighting against a numerically superior army, he defeated Dou Jiande (573- 621) in Luoyang at the Battle of Hulao on May 28, 621. In a violent removal of the royal family due to fear of assassination, Li Shimin ambushed and killed two of his brothers, Li Yuanji (b. 603) and Crown Prince Li Jiancheng (b. 589), in the Xuanwu Gate incident on July 2, 626. Shortly thereafter, his father abdicated in his favor, and Li Shimin ascended the throne. He is conventionally known by his temple name Taizong.

Although killing two brothers and laying down his father contradicted the Confucian value of filial piety, Taizong proved to be an able leader who listened to the advice of the wisest members of his council. In 628, Emperor Taizong celebrated a Buddhist memorial service for the victims of the war, and in 629 he had Buddhist monasteries erected at the sites of major battles so that monks could pray for the fallen on both sides of the fighting. This was during the Tang campaign against the Eastern Turks, in which the Eastern Turkic Khanate was destroyed after the capture of its ruler, Illig Qaghan, by the famous Tang military officer Jing Li (571-649); who later became a chancellor of the Tang dynasty. With this victory, the Turks accepted Taizong as their Great Khan, a title bestowed as Tian Kehan, in addition to his rule as Emperor of China under the traditional title of 'Son of Heaven'. Taizong was succeeded by his son Li Zhi (as Emperor Gaozong) in 649.

The usurpation of Wu Zetian

Though she entered Emperor Gaozong's court as the lowly consort Wu Wei Liang, Wu Zetian rose to the highest seat of power in 690, establishing the short-lived Wu Zhou. Empress Wu's rise to power was achieved through cruel and calculating tactics: a popular conspiracy theory stated that she killed her own child and blamed Gaozong's empress so that the empress was demoted. Emperor Gaozong suffered a stroke in 655 and Wu began making many judicial decisions for him, discussing matters of state with his advisers, who took orders from her while she sat behind a screen. When Empress Wu's eldest son, Prince heir, began to assert his authority and advocate policies opposed by Empress Wu, died suddenly in 675. Many suspected that he was poisoned by Empress Wu. Although the next heir apparently kept a lower profile, in 680 he was accused by Wu of planning a rebellion and was banished (later forced to commit suicide).

In 683, Emperor Gaozong died. He was succeeded by Emperor Zhongzong, his eldest surviving son by Wu. Zhongzong attempted to appoint his wife's father as chancellor: after only six weeks on the throne, Empress Wu deposed him in favor of her younger brother Emperor Ruizong. This caused a group of Tang princes to revolt in 684. The Wu armies suppressed them within two months. She proclaimed the Tianshou era of Wu Zhou on October 16, 690, and three days later demoted Emperor Ruizong to crown prince. He was also forced to renounce his family name. father Li in favor of Empress Wu. She then ruled as China's sole empress reign.

A coup on February 20, 705 forced Empress Wu to relinquish her post on February 22. The next day, her son Zhongzong was restored to power; the Tang were formally restored on March 3. She died soon after. To legitimize his rule, he circulated a document known as the "Great Cloud Sutra", which predicted that a reincarnation of Maitreya Buddha would be a monarch who would dispel disease, worry, and disaster from the world. He even introduced numerous revised script characters into the written language, which reverted to the originals after his death. Arguably the most important part of his legacy was to lessen the hegemony of the northwestern aristocracy, allowing people from other clans to and regions of China to be more represented in Chinese politics and government.

Reign of Emperor Xuanzong

There were many prominent women at court during and after Wu's reign, including Shangguan Wan'er (664–710), a poet, writer, and trusted official in charge of Wu's private office. In 706, Emperor Zhongzong of Tang's wife, Empress Wei (d. 710), persuaded her husband to work in government offices with her sister and daughters, and in 709 requested that he grant women the right to bequeath hereditary privileges to his sons (previously only a male right). Empress Wei eventually poisoned Zhongzong, placing her fifteen-year-old son on the throne in 710. Two weeks later, Li Longji (the last emperor Xuanzong) entered the palace with a few followers and killed Empress Wei and her faction. He then installed his father Emperor Ruizong (r. 710–712) on the throne. Just as Emperor Zhongzong was dominated by Empress Wei, Ruizong was also dominated by Princess Taiping. This finally ended when the coup de Princess Taiping ruled in 712 (later hanged herself in 713), and Emperor Ruizong abdicated in Emperor Xuanzong.

During Emperor Xuanzong's 44-year reign, the Tang dynasty reached its heyday, a golden age of low economic inflation and a toned-down lifestyle for the imperial court. Seen as a progressive and benevolent ruler, Xuanzong he even abolished the death penalty in the year 747; all executions had to be approved in advance by the emperor himself (there were relatively few, considering there were only 24 executions in 730). Xuanzong bowed to the consensus of his ministers on political decisions and made efforts to hire government ministries fairly with different political factions. His staunch Confucian chancellor Zhang Jiuling (673–740) worked to reduce deflation and increase the money supply by maintaining the use of private currencies, while his aristocratic and technocratic successor, Li Linfu (d. 753), favored a government monopoly on coinage. After 737, most of Xuanzong's confidence rested in his former chancellor Li Linfu, who advocated a more aggressive foreign policy than employs non-Chinese generals. This policy eventually created the conditions for a mass rebellion against Xuanzong.

An Lushan rebellion and catastrophe

The Tang Empire was at its height until the middle of the 8th century, when the An Lushan Rebellion (December 16 755 - February 17, 763) destroyed the prosperity of the empire. An Lushan was a half-Sogdian, half-Turkish commander from 744, he had experience fighting the Khitans of Manchuria with a victory in 744, but most of his campaigns against the Khitans were unsuccessful. He was given great responsibility in Hebei, allowing him to revolt with an army of over 100,000 troops. After capturing Luoyang, he appointed himself emperor of a new but short-lived state of Yan. Despite early victories by the Tang general Guo Ziyi (697–781), the army's newly recruited troops in the capital were no match for An Lushan's frontier veterans, so the court fled Chang'an. While the heir apparent raised troops in Shanxi and Xuanzong fled to Sichuan province, they asked for the help of the Uyghur Khanate in 756. The Uyghur Khan Moyanchur was very enthusiastic about this prospect and married his daughter to the Chinese diplomatic envoy once he arrived, receiving in turn a Chinese princess as a bride. The Uyghurs helped recapture the Tang capital from the rebels, but refused to leave until the Tang paid them a huge sum of tribute in silk. Even the Abbasid Arabs helped the Tang to put down the An Lushan rebellion. The Tibetans seized the opportunity and attacked many areas under Chinese control, and even after the Tibetan Empire collapsed in 842 (and the Uyghurs shortly thereafter), the Tang were in no position to fight back. reconquer Central Asia after 763. So significant was this loss that half a century later candidates for the jinshi exam were required to write an essay on the causes of Tang's decline. Although An Lushan was assassinated by one of his eunuchs in 757, this time of trouble and widespread insurrection continued until the rebel Shi Siming was assassinated by his own son in 763.

One of the legacies of Tang rule since 710 was the gradual rise of regional military governors, the jiedushi, who slowly came to challenge the power of the central government. the An Lushan Rebellion, the autonomous power and authority accumulated by the jiedushi in Hebei went beyond the control of the central government. After a series of rebellions between 781 and 784 in present-day Hebei, Shandong, Hubei, and Henan provinces, the government had to officially recognize the hereditary ruling of the jiedushi without accreditation. The Tang government relied on these governors and their armies for their protection and to suppress locals who would take up arms against the government. In return, the central government would recognize the rights of these governors to maintain their army, collect taxes, and even pass their title on to heirs. As time went on, these military governors gradually eliminated the importance of civil officials drafted by examinations and became more autonomous from central authority. The rule of these powerful military governors lasted until 960, when a new civil order was established under the Song dynasty. Furthermore, the abandonment of the equal field system meant that people could freely buy and sell land. Many poor people fell into debt because of this, forced to sell their land to the rich, leading to the exponential growth of large estates. With the collapse of the land allotment system after 755, the Chinese central state hardly interfered in the management agricultural and simply acted as a tax collector for about a millennium, barring a few instances such as the failed nationalization of the Song during the war of the 13th century with the Mongols.

With the collapse of central government authority over the various regions of the empire, it is recorded in 845 that bandits and river pirates in parties of 100 or more began pillaging settlements along the Yangtze River with little resistance. In 858, enormous floods along the Grand Canal inundated vast tracts of land and terrain on the North China Plain, drowning tens of thousands of people in the process. The Chinese belief in the Mandate of Heaven bestowed on The ailing Tang was also questioned when natural calamities occurred, forcing many to believe that the Heavens were displeased and that the Tang had forfeited their right to rule. Then, in 873, a disastrous harvest shook the foundations of the empire; in some areas, only half of all agricultural products were gathered, and tens of thousands faced famine and shortage. In the earlier Tang period, the central government was able to face crop crises, as recorded from 714– 719 that the Tang government responded effectively to natural disasters by extending the granary system of price regulation throughout the country. The central government was then able to build up a large stock of food surpluses to stave off the growing danger of famine and increase the agricultural productivity through land reclamation. However, in the IX century, the Tang government was almost defenseless in the face of any calamity.

Reconstruction and recovery

Although these natural calamities and rebellions tarnished the reputation and hampered the effectiveness of central government, by the early IX century, considered a period of recovery for the Tang dynasty. The government's withdrawal from its role in running the economy had the unintended effect of stimulating trade, as more markets opened up with fewer bureaucratic restrictions. By 780, the old grain and labor service tax of the VII century was replaced by a semi-annual tax paid in cash, which it meant the shift to a money economy driven by the merchant class. Cities in the Jiangnan region to the south, such as Yangzhou, Suzhou, and Hangzhou, prospered economically during the late Tang period. The government's monopoly on salt production weakened after the An Lushan Rebellion, it was placed under the Salt Commission, which became one of the most powerful state agencies, headed by capable ministers chosen as specialists. The commission began the practice of selling merchants the rights to buy monopoly salt, which they would then transport and sell in local markets. In 799, salt accounted for more than half of government revenue. S.A.M. Adshead writes that this tax on salt represents "the first time that an indirect tax, rather than tribute, levy on land or persons, or profits from state enterprises such as mines, had been the main resource of a important status". Even after the power of the central government was in decline after the middle of the VIII century, it could still function and give imperial orders on a large scale. The Tangshu (Old Book of Tang) compiled in 945 recorded that in 828 the Tang government issued a decree that standardized irrigation square-vane chain pumps in the country:

In the second year of the reign of Taihe [828], in the second month... the palace issued a standard model of the chain pump and the emperor ordered the people of Jingzhao Fu (the capital) to make a considerable number of machines for distribution to people along the Zheng Bai channel, for irrigation purposes.

The last great ambitious ruler of the Tang dynasty was Emperor Xianzong (r. 805–820), whose reign was aided by tax reforms in the 780s, including a government monopoly on the salt industry. He also had an effective and well-trained imperial army stationed in the capital led by his court eunuchs; this was the Army of Divine Strategy, with a strength of 240,000 men as recorded in 798. Between the years 806 and 819, Emperor Xianzong conducted seven major military campaigns to put down rebellious provinces that had claimed autonomy. from central authority, managing to subdue all but two of them. Under his reign there was a brief end to hereditary jiedushi, as Xianzong appointed his own military officers and rehired regional bureaucracies with civil servants. However, Xianzong's successors proved less able and more interested in the leisure of hunting, feasting, and playing sports in the open air, allowing the eunuchs to amass more power as the Recruited academic officials caused conflicts in the bureaucracy with factional parties. The power of the eunuchs was left unchallenged after Emperor Wenzong (r. 826–840) failed the plot to overthrow them; instead, Emperor Wenzong's allies were publicly executed in Chang'an's western market, by order of the eunuchs.

However, the Tang managed to restore at least indirect control over former Tang territories as far west as the Hexi Corridor and Dunhuang in Gansu. In 848, the Han Chinese general Zhang Yichao (799–872) managed to wrest control of the region from the Tibetan Empire during their civil war. Soon after, Emperor Xuānzong of Tang (r. 846–859) recognized Zhang as the protector (防禦使, Fangyushi) of Sha Prefecture and military governor jiedushi of the new Guiyi Circuit.

End of Dynasty

In addition to natural calamities and jiedushi accumulating autonomous control, the Huang Chao Rebellion (874–884) resulted in the sacking of Chang'an and Luoyang and took an entire decade to complete. suppressed. Although the rebellion was defeated by the Tang, it never recovered from that crucial blow, weakening it for future military powers to take over. There were also large groups of bandits, the size of small armies, that ravaged the countryside in the later years of the Tang, smuggling illicit salt, ambushing merchants and convoys, and even besieging several walled cities.

Zhu Wen, originally a salt smuggler who had served under the rebel Huang Chao, surrendered to the Tang forces. Helping to defeat Huang, he was renamed Zhu Quanzhong and was awarded a series of rapid military promotions to the military governor of Xuanwu Circuit.Zhu later conquered many circuits and became the most powerful warlord. In 903 he controlled the imperial court and forced Emperor Zhaozong of Tang to move the capital to Luoyang, preparing to seize the throne himself. In 904, Zhu assassinated Emperor Zhaozong to replace him with the emperor's young son, Emperor Ai of Tang. In 905, Zhu executed 9 of Emperor Ai's brothers, as well as many officials and Empress Dowager He. In 907, the Tang dynasty ended when Zhu deposed Ai and took the throne for himself (posthumously known as the 'Taizu Emperor of Later Liang'). He established the later Liang, which ushered in the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period. A year later, Zhu had the deposed Emperor Ai poisoned.

Administration and politics

Taizong set out to solve internal problems within the government that had constantly plagued past dynasties. Based on the Sui legal code, he issued a new legal code upon which subsequent Chinese dynasties would model theirs, as well as neighboring policies in Vietnam, Korea, and Japan. The earliest surviving legal code was established in the year 653, which was divided into 500 articles specifying different offenses and penalties ranging from ten strokes with a light stick, one hundred strokes with a heavy rod, exile, penal servitude, or execution.

The legal code distinguished different levels of severity in the punishments imposed when different members of the social and political hierarchy committed the same crime. For example, the severity of the punishment was different when a servant or nephew killed a teacher or a uncle than when a master or uncle killed a servant or nephew.

The Tang Code was largely retained by later codes, such as the Ming dynasty (1368–1644) code of 1397, but there were several revisions in later times, such as the improvement of women's property rights during the Song dynasty (960–1279).

The Tang had three departments (Traditional Chinese 省), which were tasked with drafting, reviewing, and implementing policies, respectively. There were also six ministries (Traditional Chinese 部) under the administrations that implemented the policy, each of which was assigned different tasks. These three departments and six ministries included personnel administration, finance, rites, military, justice, and public works, an administrative model that would last until the fall of the Qing dynasty (1644-1912).

Though the Tang founders were associated with the glory of the earlier Han dynasty (III century BCE- III century AD), the basis for much of their administrative organization was very similar to that of the earlier southern and southern dynasties. The Tang continued the Northern Zhou (VI century) fubing system of divisional militias, along with farmers soldiers who served in rotation from the capital or the frontier to receive appropriate farmland. The equitable land system of the Northern Wei (4th and 6th centuries) was also retained, although there were some modifications.

Although the central and local governments kept enormous amounts of records on land ownership to assess taxes, it became common practice in Tang for literate and well-to-do people to create their own private documents and sign contracts. These had your own signature and that of a witness and scribe to prove in court (if necessary) that your property claim was legitimate. The prototype for this actually existed as far back as the ancient Han dynasty, while contractual language became even more common and embedded in Chinese literary culture in later dynasties.

The center of Tang political power was the capital city of Chang'an (present-day Xi'an), where the emperor maintained his great palace quarters and entertained political emissaries with music, sports, acrobatics, poetry, paintings, dramatic works and theatrical performances. The capital was also filled with incredible amounts of wealth and resources to spare. When Chinese prefectural government officials traveled to the capital in 643 to give the annual report on affairs in their districts, Emperor Taizong discovered that many did not have proper lodgings to rest in and were renting rooms with merchants. Therefore, Emperor Taizong ordered the government agencies in charge of municipal construction to build each visiting official his own private mansion in the capital.

Imperial Exams

Students of Confucian studies were potential candidates for imperial examinations, graduates of which could be appointed state bureaucrats in local, provincial, and central government. Two types of exams were given: mingjing (明經 “illuminating the classics”) and jinshi (進士; "presented scholar"). The mingjing was based on the Confucian classics and tried the student's knowledge of a wide variety of texts. The jinshi tested a student's literary skills by writing essay-style responses to questions on government and political issues, as well as their abilities to compose poetry Candidates were also judged on their deportation skills, appearance, speech, and calligraphy skill level, all of which were subjective criteria that allowed already wealthy members of society to be chosen over those of more modest means who could not. to be educated in rhetoric or imaginative writing skills. There were a disproportionate number of civil servants coming from aristocratic rather than non-aristocratic families. The exams were open to all male subjects whose fathers did not belong to the artisan or merchant classes, although having wealth or noble status was not a prerequisite for receiving a recommendation. To promote widespread Confucian education, the Tang government established state schools and issued standard versions of the Five Classics with selected commentaries.

This competitive procedure was designed to attract the best talent to government. But perhaps an even greater consideration for the Tang rulers, aware that imperial reliance on powerful aristocratic families and warlords would have destabilizing consequences, was to create a corps of career civil servants who do not have an autonomous territorial or functional power base.. The Tang law code guaranteed the equal division of inherited property among legitimate heirs, allowing some social mobility and preventing the families of powerful court officials from becoming nobility through primogeniture. Thus, these academic officials gained status in their local communities and family ties, while also sharing values that connected them to the imperial court. From Tang times to the end of the Qing dynasty in 1912, academic officials often functioned as intermediaries between the grassroots level and the government. However, the potential of a widespread examination system was not fully realized until the Song dynasty, when the merit-driven academic official largely abandoned his aristocratic habits and defined his social status through the examination system. As historian Patricia Ebrey states of the Song academic period:

The examination system, used only on a small scale in Sui and Tang times, played a central role in creating this new elite. The first Song emperors, particularly concerned about avoiding the dominance of the government by the military, greatly expanded the civil service review system and the government's school system.

Religion and politics

From the beginning, religion played a central role in Tang politics. In his bid for power, Li Yuan had attracted followers by claiming descent from the Taoist sage Laozi (6th century BCE BCE)..). Individuals running for office will have monks from Buddhist temples pray for them in public in exchange for cash donations or gifts if the person is selected. Before the persecution of Buddhism in the 9th century century, Buddhism and Taoism were accepted side by side, and the Emperor Xuanzong (r. 712-756) invited monks and clerics of both faiths to his court. At the same time, Xuanzong exalted ancient Laozi by bestowing great titles on him, wrote commentaries on Daoist Laozi, established a school to prepare candidates for Daoist scripture examinations, and called on the Indian monk Vajrabodhi (671–741) to perform tantric rites. to prevent a drought in 726. In 742, Emperor Xuanzong personally held the incense burner during a ceremony led by Amoghavajra (705-774, patriarch of the Shingon school) reciting 'mystic incantations' to ensure the victory of the Tang forces.

While religion played a role in politics, politics also played a key role in religion. In 714, Emperor Xuanzong prohibited shops and vendors in the city of Chang'an from selling copied Buddhist sutras, instead giving Buddhist clergy in monasteries the exclusive right to distribute sutras to laymen. The previous year of 713, Emperor Xuanzong had liquidated the highly lucrative inexhaustible treasury, which was run by a prominent Buddhist monastery in Chang'an. This monastery collected large amounts of money, silk, and treasures through repentance crowds from anonymous people, leaving the donations on the monastery premise. Although the monastery was generous in donations, Emperor Xuanzong issued a decree abolishing its treasury on the grounds that its banking practices were fraudulent, pooling its wealth and distributing the wealth to various other Buddhist monasteries and Taoist abbeys and to repair statues, halls and bridges in the city.

Taxes and Census

The Tang Dynasty government attempted to create an accurate census of the population size of its empire, mainly for effective taxation and military conscription matters for each region. The early Tang government set both the grain tax and the cloth tax at a relatively low rate for every household under the empire. This was for the purpose of encouraging households to enroll in taxes and not bypassing the authorities, thus providing the government with the most accurate estimate possible. In the 609 census, the population was counted by government efforts at a size of 9 million households, or about 50 million people. The Tang census of 742 again approximated the population size of China to about 50 million people. Patricia Ebrey writes that even if a fairly significant number of people would have avoided the fiscal census registration process, the population size during the Tang dynasty had not increased significantly since the previous Han dynasty (the Year 2 census recorded a population of approximately 58 million people in China). S.A.M. Adshead disagrees, estimating that there were around 75 million people around 750.

At the 754 Tang census, there were 1,859 cities, 321 prefectures, and 1,538 counties in the entire empire. Although there were many large and prominent cities during the Tang dynasty, rural and agrarian areas comprised the majority of the population China by 80 to 90%. There was also a dramatic population migration shift from north to south China, as the North had 75% of the overall population at the start of the dynasty, but declined by the end. at 50%.

The size of the Chinese population would not increase dramatically until the Song Dynasty period, when the population doubled to 100 million people due to extensive rice cultivation in central and southern China, along with rural farmers who they had more abundant food yields that they could easily provide for the growing market.

Military and foreign policy

Protectorates and tributaries

The 7th century and first half of the 8th century are generally considered the era in which the Tang reached the zenith of its can. In this period, Tang control extended further west than any previous dynasty, stretching from northern Vietnam in the south, to a point north of Kashmir bordering Persia in the west, to northern Korea in the northeast..

Some of the kingdoms that paid tribute to the Tang dynasty were Kashmir, Nepal, Khotan, Kucha, Kashgar, Silla, Champa, and kingdoms located in the valley of Amu Darya and Syr Darya. Turkic nomads turned to the Emperor of Tang China as Tian Kehan. Gaozong established several protectorates governed by a Protectorate General or Grand Protectorate General, which extended the Chinese sphere of influence as far as Herat in western Afghanistan. Protectorate generals were given great autonomy to handle local crises without waiting for central admission. After Xuanzong's reign, military governors (jiedushi) were granted enormous power, including the ability to maintain their own armies, collect taxes, and pass on their titles hereditarily. This is commonly recognized as the beginning of the fall of the central Tang government.

Soldiers and Recruitment

By 737, Emperor Xuanzong scrapped the policy of conscripting soldiers who were replaced every three years, replacing them with tougher, more battle-efficient long-service soldiers. It was also more economically feasible, as training new recruits and sending them to the frontier every three years drained the treasury. By the end of the VII century , fubing troops began to abandon military service and the homes provided for them on the equal-field system. The supposed standard 100 mu of land allotted to each family was dwindling in size where the population expanded and the wealthy bought up most of the land. Then, hard-pressed peasants and vagabonds were inducted into military service with exemption benefits from both tax and corvée labor service, as well as provisions for farmland and housing for dependents accompanying soldiers on the frontier. By 742, the total number of troops enlisted in Tang armies it had grown to about 500,000 men.

Eastern Regions

In East Asia, Tang Chinese military campaigns were less successful elsewhere than in earlier Chinese imperial dynasties. Like the Sui dynasty emperors before him, Taizong established a military campaign in 644 against the Korean kingdom of Goguryeo in the Goguryeo-Tang War; however, this led to their withdrawal in the first campaign because they failed to overcome the successful defense led by General Yeon Gaesomun. Allied with the Korean Kingdom of Silla, the Chinese fought Baekje and their Japanese Yamato allies at the Battle of Baekgang in August 663, a decisive Tang-Silla victory. The Tang dynasty navy had several different types of ships at its disposal to engage in naval warfare, these ships described by Li Quan in his Taipai Yinjing ("White and Shadowy War Planet Canon") of 759. The Battle of Baekgang was actually a restoration movement by the remnant forces of Baekje, as their kingdom was overthrown in 660 by a joint Tang-Silla invasion, led by the Chinese general Su Dingfang and the Korean general Kim Yushin (595-673). In another joint invasion with Silla, the Tang army severely weakened the Goguryeo Kingdom in the north by driving out its outer strongholds in 645. With joint attacks by the Silla and Tang armies under commander Li Shiji (594–669), the Goguryeo Kingdom was destroyed by 668.

Although formerly enemies, the Tang accepted Goguryeo officials and generals into their administration and military, such as the brothers Yeon Namsaeng (634-679) and Yeon Namsan (639-701). From 668 to 676, the Tang Empire would control northern Korea. However, in 671 Silla broke the alliance and the Silla-Tang War began to drive out the Tang forces. At the same time, the Tang faced threats on its western border when a large Chinese army was defeated by the Tibetans at the Dafei River in 670. In 676, the Tang army was driven out of Korea by the unified Silla. Eastern Turks in 679, the Tang abandoned their Korean campaigns.

Although the Tang had fought against the Japanese, they still had cordial relations with Japan. There were numerous imperial embassies to China from Japan, diplomatic missions that were not stopped until 894 by Emperor Uda (r. 887-897), after persuasion by Sugawara no Michizane (845-903). The Japanese Emperor Tenmu (r. 672-686) even established his recruited army on the Chinese model, his state ceremonies on the Chinese model, and built his palace at Fujiwara on the Chinese architectural model.

Many Chinese Buddhist monks came to Japan to help promote the spread of Buddhism as well. Two monks of the 7th century in particular, Zhi Yu and Zhi You, visited the court of Emperor Tenji (r. 661-672), whereupon they presented a gift of a south-pointing chariot they had crafted. This century mechanically driven directional compass vehicle III (using a differential gear) was reproduced again in various models for Tenji in 666, as recorded in the Nihon Shoki of 720. Japanese monks also visited China; such was the case with Ennin (794–864), who wrote of his travel experiences, including voyages along China's Grand Canal. The Japanese monk Enchin (814–891) stayed in China from 839 to 847 and again from 853 to 858, landing near Fuzhou, Fujian and setting sail for Japan from Taizhou, Zhejiang during his second voyage to China.

Western and Northern Regions

The Sui and Tang conducted highly successful military campaigns against the steppe nomads. Chinese foreign policy to the north and west now had to deal with the nomadic Turks, who were becoming the most dominant ethnic group in Central Asia. To manage and avoid any threat posed by the Turks, the Sui government repaired fortifications and received their trade and tribute missions. They sent four royal princesses to form marriage alliances with Turkic clan leaders, in 597, 599, 614, and 617. The Sui stirred up trouble and conflict between the ethnic groups against the Turks As early as the Sui dynasty, the Turks had become a major militarized force in the employ of the Chinese. When the Khitans began attacking northeast China in 605, a Chinese general led 20,000 Turks against them, distributing Khitan women and cattle to the Turks as rewards. On two occasions, between 635 and 636, the royal princesses of Tang they married Turkish mercenaries or generals in Chinese service. Throughout the Tang dynasty until the end of 755, there were approximately ten Turkish generals serving under the Tang. Although most of the Tang army consisted of by Chinese conscripts, most of the troops led by Turkish generals were of non-Chinese origin, campaigning largely on the western border, where combat troop presence was low. Some "Turkish" they were Han Chinese nomads, a deinized people.

Civil war in China subsided almost entirely in 626, along with the defeat in 628 of the Chinese warlord of Ordos, Liang Shidu; after these internal conflicts, the Tang began an offensive against the Turks. In AD 630, Tang armies captured areas of the Ordos desert, present-day Inner Mongolia province, and southern Mongolia from the Turks. In this military victory, Emperor Taizong gained the title of Great Khan among the various Turks in the region who pledged their allegiance to him and the Chinese empire (with several thousand Turks traveling to China to live in Chang'an). On June 11, 631, Emperor Taizong also sent envoys to Xueyantuo with gold and silk to persuade the release of enslaved Chinese prisoners who were captured during the Sui to Tang transition from the northern border; this embassy managed to free 80,000 Chinese men and women who were later returned to China.

While the Turks settled in the Ordos region (former Xiongnu territory), the Tang government adopted the military policy of dominating the central steppe. Like the Han dynasty before it, the Tang dynasty (along with Turkic allies) conquered and subdued Central Asia during the 640s and 650s. During the reign of Emperor Taizong alone, major campaigns were launched not only against the köktürk, but also separate campaigns against the Tuyuhun, the oasis city-states, and the Xueyantuo. Under Emperor Gaozong, a campaign led by General Su Dingfang was launched against the Western Turks ruled by Ashina Helu.

The Tang Empire competed with the Tibetan Empire for control of areas in Inner and Central Asia, which was sometimes resolved by marriage alliances such as the marriage of Princess Wencheng (died 680) to Songtsän Gampo (died 649) A Tibetan tradition mentions that Chinese troops captured Lhasa after the death of Songtsän Gampo, but no such invasion is mentioned in either Chinese annals or Tibetan Dunhuang manuscripts.

There was a long series of conflicts with Tibet over territories in the Tarim Basin between 670-692, and in 763 the Tibetans even captured the Chinese capital Chang'an for a fortnight during the An Shi Rebellion. In fact, it was during this rebellion that the Tang withdrew his western garrisons stationed in what is now Gansu and Qinghai, which the Tibetans occupied along with territory in what is now Xinjiang. Hostilities between the Tang and Tibet continued until they signed a formal peace treaty in 821. The terms of this treaty, including fixed borders between the two countries, are recorded in a bilingual inscription on a stone pillar outside the Jokhang Temple in Lhasa.

During the Islamic conquest of Persia (633–656), the son of the last ruler of the Sasanian empire, Prince Pirooz, fled to Tang China. According to the Old Book of Tang, Pirooz was appointed head of a Persian governorate in what is now Zaranj, Afghanistan. During this conquest of Persia, the Islamic caliph Rashidun Uthman ibn Affan (r. 644–656) sent an embassy to the Tang court at Chang'an. Arab sources claim that the Umayyad commander Qutayba ibn Muslim briefly seized Kashgar from China and withdrew after an agreement, but modern historians discount this claim entirely. The Umayyad Arab Caliphate in 715 removed Ikhshid, the king of the Fergana Valley, and installed a new king Alutar on the throne. The deposed king fled to Kucha (seat of the Anxi Protectorate) and sought Chinese intervention. The Chinese sent 10,000 troops under Zhang Xiaosong to Ferghana. He defeated Alutar and the Arab occupation force at Namangan and reinstated Ikhshid on the throne. The Chinese of the Tang dynasty defeated the invading Umayyad Arabs at the Battle of Aksu (717). The Umayyad Arab commander Al-Yashkuri and his army fled to Tashkent after being defeated.The Turgesh then crushed the Arab Umayyads and drove them out. By the 740s, Arabs under the Abbasid Caliphate in Khorasan had re-established their presence in the Ferghana Basin and in Sogdiana. At the Battle of Talas in 751, Qarluq mercenaries under the Chinese defected, helping the Arab armies of the Islamic Caliphate defeat the Tang force under commander Gao Xianzhi. Although the battle itself was not of the greatest military importance, this was a pivotal moment in history; marks the spread of Chinese papermaking in the western regions of China when captured Chinese soldiers revealed secrets of Chinese papermaking to the Arabs. These techniques eventually reached Europe in the 12th century via Moorish-controlled Spain. Although they had fought in Talas, on June 11, 758, an Abbasid embassy arrived in Chang'an simultaneously with the Uyghur Turks carrying gifts for the Tang Emperor. In 788-89, the Chinese concluded a military alliance with the Uyghur Turks which they defeated twice to the Tibetans, in 789 near the city of Gaochang in Dzungaria, and in 791 near Ningxia on the Yellow River.

Joseph Needham writes that a tributary embassy arrived at Emperor Taizong's court in 643 from the Patriarch of Antioch. However, Friedrich Hirth and other Sinologists such as H.A.M. Adshead has identified Fu lin (拂菻) in the Old Book and New Book of Tang as the Byzantine Empire, which those stories directly associated with Daqin (i.e., the Roman Empire). The embassy sent in 643 by Boduoli (波多力) was identified as the Byzantine ruler Constant II Pogonatos (Kōnstantinos Pogonatos or "Constantine the Bearded") and more embassies sent to the VIII century. S.A.M. Adshead offers a different transliteration derived from "patriarch" or "patrician", possibly a reference to one of the acting regents for the young Byzantine monarch. The Old and New Book of Tang also provides a description of the Byzantine capital of Constantinople, including how it was besieged by the Da shi (大食, i.e. Umayyad Caliphate) forces of Muawiyah I, who forced them to surrender homage to the Arabs. The Byzantine historian of the VII century Theophylact Simocates wrote about the reunification of northern and southern China by the Sui dynasty (dating from the time of Emperor Mauritius); the capital city of Khubdan (from Old Turkic Khumdan, meaning Chang'an); the basic geography of China, including its former political division around the Yangtze River; the name of the Chinese ruler Taisson meaning "Son of God", but possibly derived from the name of the contemporary ruler Emperor Taizong.

Economy

By using land trade along the Silk Road and maritime trade by sailing the sea, the Tang were able to acquire and obtain many new technologies, cultural practices, rare luxuries, and contemporary items. From Europe, the Middle East, Central and South Asia, the Tang dynasty was able to acquire new fashion ideas, new types of pottery, and improved silver-forging techniques. The Tang Chinese also gradually adopted the foreign concept of stools and chairs as seats., while the Chinese beforehand always sat on mats placed on the floor. In the Middle East, the Islamic world coveted and bought in bulk Chinese goods such as silks, lacquerware, and chinaware. Songs, dances, and musical instruments from regions Foreign instruments became popular in China during the Tang dynasty. These musical instruments included oboes, flutes, and small lacquered drums from Kucha in the Tarim Basin, and percussion instruments from India, such as cymbals. At court there were nine musical ensembles (expanded from seven in the Sui dynasty) representing music from all over Asia.

There was great contact with and interest in India as a center for Buddhist knowledge, with famous travelers such as Xuanzang (died 664) visiting the South Asian state. After a 17-year journey, Xuanzang managed to recover valuable Sanskrit texts for translation into Chinese. There was also a Turkic-Chinese dictionary available for scholars and serious students, while Turkic folk songs inspired some Chinese poetry. Within China, trade was facilitated by the Grand Canal and the Tang government's rationalization of the system. of increased canals which reduced the costs of transporting grain and other basic products. The state also managed approximately 32,100 km of postal service routes by horse or boat.

Silk Road

Although the Silk Road from China to Europe and the Western world was initially formulated during the reign of Emperor Wu (141–87 BCE) during the Han dynasty, it was reopened by the Tang in 639 when Hou Junji (died 643) conquered the West and remained open for nearly four decades. It was closed after the Tibetans captured it in 678, but in 699, during the period of Empress Wu, the Silk Road reopened when the Tang recaptured the Four Garrisons of Anxi originally installed in 640, once again connecting China. directly to the West by land trade.

The Tang captured the vital route through the Gilgit Valley from Tibet in 722, lost it to the Tibetans in 737, and recaptured it under the Goguryeo-Korean general Gao Xianzhi. When the An Lushan rebellion ended by 763, the Tang Empire had once again lost control over its western lands, as the Tibetan Empire largely cut off China's direct access to the Silk Road. An internal rebellion in 848 overthrew the Tibetan rulers and Tang China regained its northwestern prefectures from Tibet in 851. These lands contained crucial grazing areas and pastures for raising horses that the Tang dynasty desperately needed.

Despite the many expatriate European travelers who came to China to live and trade, many travelers, mainly religious monks and missionaries, witnessed the strict border laws enforced by the Chinese. As the monk Xuanzang and many other monk travelers assured, there were many Chinese government checkpoints along the Silk Road that examined travel permits to the Tang Empire. In addition, banditry was a problem at checkpoints and oasis cities, as Xuanzang also reported that his traveling party was robbed by bandits on multiple occasions.

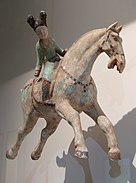

The Silk Road also affected the art of the Tang dynasty. Horses became a significant symbol of prosperity and power, as well as an instrument of military and diplomatic policy. Horses were also revered as a relative of the dragon.

Ports and maritime trade

Chinese envoys have been sailing across the Indian Ocean to India since perhaps the II century BCE. However, it was during the Tang dynasty that a strong Chinese maritime presence could be found in the Persian Gulf and Red Sea, in Persia, Mesopotamia (sailing the Euphrates River in present-day Iraq), Arabia, Egypt in Middle East and Aksum (Ethiopia) and Somalia in the Horn of Africa.

During the Tang Dynasty, thousands of expatriate foreign merchants came and lived in numerous Chinese cities to do business with China, including Persians, Arabs, Hindu Indians, Malays, Bengalis, Sinhalese, Khmers, Chams, Jews, and Eastern Nestorian Christians Proximity, among many others. In 748, the Buddhist monk Jian Zhen described Guangzhou as a bustling mercantile trade center where many large and impressive foreign ships came to dock. He wrote that "many big ships came from Borneo, Persia, Quunglun (Indonesia/Java)... with spices, pearls and jade piled up in mountains", as it is written in the Yue Jue Shu (lost Yue state records). During the An Lushan Rebellion, Arab and Persian pirates burned and sacked Guangzhou in 758, and foreigners were massacred in Yangzhou in 760. The Tang government reacted by closing the Guangdong port for approximately five decades, and foreign ships docked in Hanoi. However, when the port reopened, it continued to prosper. In 851, the Arab merchant Sulaiman al-Tajir observed the manufacture of Chinese porcelain in Guangzhou and admired its transparent quality. He also provided a description of the Guangzhou mosque, its granaries, local government administration, some of its written records, the treatment of travelers, along with the use of pottery, rice wine, and tea. However, in another bloody episode in Guangzhou in 879, the Chinese rebel Huang Chao sacked the city and reportedly massacred thousands of native Han Chinese, along with foreign Jews, Christians, Zoroastrians, and Muslims in the process. Huang's rebellion was finally suppressed in 884.

Vessels from neighboring East Asian states such as Korea's Silla and Balhae and Japan's Hizen Province participated in the Yellow Sea trade, which Silla dominated. After Silla and Japan reopened renewed hostilities In the late 7th century century, most Japanese shipping merchants chose to set sail from Nagasaki for the mouth of the Huai River, the Yangzi River and even as far south as Hangzhou Bay to avoid Korean ships in the Yellow Sea. To sail back to Japan in 838, the Japanese embassy in China acquired nine ships and sixty Korean sailors from the Korean quarters of the cities of Chuzhou and Lianshui along the Huai River. Chinese commercial ships traveling to Japan are also known to set sail from various ports along the coasts of Zhejiang and Fujian provinces.

The Chinese engaged in large-scale production for export abroad at least in Tang times. This was demonstrated by the discovery of the Belitung shipwreck, a silt-preserved shipwrecked Arab dhow in the Gaspar Strait near Belitung, which contained 63,000 pieces of Tang pottery, silver and gold (including a Changsha bowl with a date: & #34;16th day of the seventh month of the second year of Baoli's reign, or 826, roughly confirmed by radiocarbon dating of the star anise in the shipwreck). Starting in 785, the Chinese began regularly calling Sufala on the East African coast to cut out Arab middlemen, with several contemporary Chinese sources giving detailed descriptions of trade in Africa. The official and geographer Jia Dan (730–805) wrote of two sea trade routes common in his day: one from the coast of the Bohai Sea to Korea and another from Guangzhou via Malacca to the Nicobar Islands, Sri Lanka, and India, the eastern and northern shores of the Arabian Sea to the Euphrates River. In 863, the Chinese author Duan Chengshi (d. 863) provided a detailed description of the slave trade, ivory trade, and ambergris trade in a country called Bobali, said by historians to have been Berbera in Somalia. In Fustat (formerly Cairo), Egypt, the fame of Chinese ceramics there led to a huge demand for Chinese wares; therefore the Chinese often traveled there (this continued in later periods such as Fatimid Egypt). From this time period, the Arab merchant Shulama once wrote of his admiration for Chinese sea junks, but noted that their draft was too deep for them to enter the Euphrates River, forcing them to carry passengers and cargo in small boats. Shulama also noted that Chinese ships were often very large, with capacities of up to 600–700 passengers.

Culture and society

Art

The Sui and Tang dynasties had turned away from the more feudal culture of the previous northern dynasties, in favor of staunchly civil Confucianism. The governmental system was supported by a large class of Confucian intellectuals selected through examinations or recommendations from the civil service. In the Tang period, Taoism and Buddhism also reigned as core ideologies and played an important role in people's daily lives. The Tang Chinese enjoyed feasting, drinking, holidays, sports, and all kinds of entertainment, while Chinese literature flourished and became more accessible with new printing methods.

Chang'an, the capital

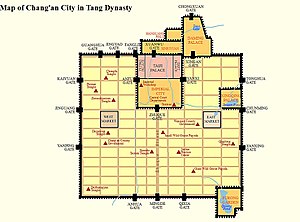

Although Chang'an was the capital of the early Han and Jin dynasties, after its subsequent destruction in war, it was the model of the Sui dynasty that comprised the capital of the Tang era. The roughly square dimensions of the city had 10 km of outer walls running east-west, and more than 8 km of outer walls running north-south. The royal palace, Taiji Palace, lay to the north of the axis. of the city. From the great Mingde gates located in the center of the southern wall, a wide city avenue stretched from there north to the central administrative city, behind which was the Chentian Gate of the royal palace, or Imperial City. Intersecting this were fourteen main streets running east-west, while eleven main streets ran north-south. These intersecting main roads formed 108 rectangular rooms with walls and four doors each, with each room being filled with multiple city blocks. The city became famous for this checkerboard pattern of main roads with walled and gated districts, its layout even mentioned in one of Du Fu's poems. During the Heian period, the city of Heian kyō (present-day Kyoto) of Japan, like many cities, was organized in the street grid pattern of the Tang capital and according to traditional geomancy following the Chang'an model. Of these 108 neighborhoods in Chang'an, two of these (each the size of two regular city quarters) were designated as government-supervised markets, and other space reserved for temples, gardens, ponds, etc. Throughout the city, there were 111 Buddhist monasteries, 41 abbeys Taoists, 38 family shrines, 2 official temples, 7 churches of foreign religions, 10 municipal districts with provincial broadcasting offices, 12 main inns, and 6 cemeteries. Some neighborhoods in the city were literally filled with open public playing fields or courtyards. backsides of luxurious mansions for playing horse polo and cuju football. In 662, Emperor Gaozong moved the imperial court to Daming Palace, which became the political center of the empire and served as the royal residence of the Tang emperors for more than 220 years.

The Tang capital was the largest city in the world at the time, with the population of the city's neighborhoods and its suburban countryside reaching two million. The Tang capital was highly cosmopolitan, with ethnicities from Persia, Asia Central, Japan, Korea, Vietnam, Tibet, India and many other places living side by side. Naturally, with this plethora of different ethnicities in Chang'an, many different religions were also practiced, including Buddhism, Nestorian Christianity, Manichaeism, Zoroastrianism, Judaism, and Islam. With widely open access to China As the Silk Road to the west facilitated, many foreign settlers were able to move east to China, while the city of Chang'an had some 25,000 foreigners living. The exotic green-eyed, blonde-haired Tocharian ladies who serving wine in agate and amber goblets, singing and dancing in taverns attracted customers. If a foreigner in China pursued a Chinese woman to marry, he was required to stay in China without being able to bring his bride back to their homeland, as outlined in a law passed in 628 to protect women from temporary marriages with foreign envoys. Several laws enforcing the segregation of foreigners from China were passed during the Tang dynasty. In 779, the Tang dynasty issued an edict that forced Uyghurs in the capital Chang'an to wear their ethnic dress, prevented them from marrying Chinese women, and prohibited them from passing as Chinese.

Chang'an was the center of central government, the home of the imperial family, and was full of splendor and wealth. However, by the way, it was not the economic center during the Tang Dynasty. The city of Yangzhou along the Grand Canal and near the Yangtze River was the largest economic center during the Tang era.

Yangzhou was the seat of the Tang government's monopoly on salt and the largest industrial center in China; it acted as a midpoint in shipping foreign goods to be organized and distributed to major cities in the north. Like Guangzhou's seaport in the south, Yangzhou was serviced by thousands of foreign merchants from all over Asia.

There was also the secondary capital city of Luoyang, which was Empress Wu's favorite capital of the two. In 691, it had more than 100,000 families (more than 500,000 people) from the entire Chang'an region move to populate Luoyang. With a population of approximately one million, Luoyang became the second largest city in the empire, and with its proximity to the Luo River it benefited from the agricultural fertility of the south and the commercial traffic of the Grand Canal. However, the Tang court eventually downgraded its capital status and did not visit Luoyang after 743, when Chang'an's problem of acquiring adequate supplies and stores for the year was resolved. As early as 736, granaries were built at critical points along the route from Yangzhou to Chang'an, eliminating shipment delays, spoilage and theft. An artificial lake used as a transshipment pool was dredged east of Chang' 39;an in 743, where curious northerners finally got to see the variety of boats found in southern China, delivering tax and tribute items to the imperial court.

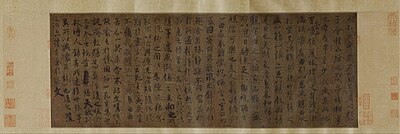

Literature

The Tang period was a golden age of Chinese literature and art. More than 48,900 poems written by some 2,200 Tang authors have survived to the present day. Chinese poetry composition skill became a compulsory study for those wishing to pass the imperial exams, while poetry was also highly prized. competitive; poetry contests between banquet guests and courtiers were very common. The most popular styles of poetry in the Tang were gushi and jintishi, with the famous poet Li Bai (701 –762) famous for the former style, and poets such as Wang Wei (701–761) and Cui Hao (704–754) famous for their use of the latter. jintishi poetry, or regulated verse, is in the form of stanzas of eight lines or seven characters per line with a fixed pattern of tones that require the second and third couplets to be antithetical (although the antithesis to it is often lost in translation into other languages.) Tang poems remained popular, and extensive emulation of Tang-era poetry began in the Song dynasty; in that period, Yan Yu (嚴羽; active 1194–1245) was the first to confer the poetry of the High Tang era (c. 713–766) with "canonical status within the classical poetic tradition". Yan Yu reserved the position of highest esteem among all Tang poets for Du Fu (712–770), who was not seen as such in his own era, and was branded by his peers as an anti-traditional rebel.

The classical prose movement was stimulated in large part by the writings of Tang authors Liu Zongyuan (773–819) and Han Yu (768–824). This new style of prose broke away from the poetic tradition of the piantiwen style (騙體文, " parallel prose") that began in the Han dynasty. Although writers of the Classical Prose Movement imitated piantiwen, they criticized it for its often vague content and lack of colloquial language, focusing more on in clarity and precision to make his writing more direct. This style of guwen (archaic prose) dates back to Han Yu, and would be largely associated with orthodox Neo-Confucianism.

Fiction and short stories were also popular during the Tang, one of the most famous being Yingying's Biography by Yuan Zhen (779–831), which was widely circulated in his own time and the Yuan dynasty (1279–1368) became the basis for plays in Chinese opera. Timothy C. Wong places this story within the larger context of Tang love stories, which often share the designs of the plot of quick passion, the inevitable peer pressure leading to abandonment of the romance, followed by a period of melancholy. Wong claims that this scheme lacks the undying vows and total commitment to love found in Western romances as Romeo and Juliet, but that the underlying traditional Chinese values of inseparable identity from one's environment (including human society) served to create the necessary fictional device of romantic tension.

There were great encyclopedias published in the Tang. The Yiwen Leiju encyclopedia was compiled in 624 by the editor Ouyang Xun (557-641), as well as Linghu Defen (582-666) and Chen Shuda (d. 635). The encyclopedia A Treatise on Astrology of the Kaiyuan Era was compiled in its entirety in 729 by Gautama Siddha (8th century< century), an Indian astronomer, astrologer and scholar born in the capital Chang'an.

Chinese geographers like Jia Dan wrote accurate descriptions of faraway places abroad. In his work written between 785 and 805, he described the sea route that entered the mouth of the Persian Gulf, and which the medieval Iranians (whom he called the Luo-He-Yi people) had erected & # 39; ornamental pillars & # 39; in the sea that acted as beacons for ships that might go astray. Confirming Jia's reports of lighthouses in the Persian Gulf, Arab writers a century after Jia wrote about the same structures, writers such as al-Mas'udi and al-Muqaddasi. The Tang dynasty Chinese diplomat Wang Xuance traveled to Magadha (northeast of present-day India) during the 7th century century. wrote the book Zhang Tianzhu Guotu (Illustrated Accounts of Central India), which included a large amount of geographical information.

Many histories from earlier dynasties were compiled between 636 and 659 by court officials during and soon after the reign of Emperor Taizong of Tang. These included the Book of Liang, the Book of Chen, the Book of Northern Qi, the Book of Zhou, the Book of Sui, the Book of Jin, the History of the Northern Dynasties, and the History of the Northern Dynasties. south. Although not included in the official Twenty-Four Histories, Tongdian and Tang Huiyao were nevertheless valuable written historical works of the Tang period. The Shitong written by Liu Zhiji in 710 was a metahistory, as it covered the history of Chinese historiography in the past centuries up to his time. The Great Tang Records in the Western Regions, compiled by Bianji, recounted the journey of Xuanzang, the most famous Buddhist monk of the Tang era.

Other important literary offerings included Miscellaneous Fragments from Youyang by Duan Chengshi (d. 863), an entertaining collection of foreign legends and rumors, reports of natural phenomena, short anecdotes, mythical and mundane tales, as well as notes on various topics. The exact literary category or classification into which Duan's grand informal narrative would fit is still debated among scholars and historians.

Religion and philosophy

Since ancient times, the Chinese believed in a traditional religion and Taoism that encompassed many deities. The Chinese believed that Tao and the afterlife were a parallel reality to the living world, complete with its own bureaucracy and afterlife currency needed by dead ancestors. Funeral practices included providing the deceased with anything they might need in the afterlife. beyond, including animals, servants, artists, hunters, households, and officials. This ideal is reflected in the art of the Tang dynasty. This is also reflected in many short stories written in Tang about people accidentally ending up in the realm of the dead, only to return and report their experiences.

Buddhism, originating in India at the time of Confucius, continued to exert its influence during the Tang period and was accepted by some members of the imperial family, becoming fully Sinicized and a permanent part of traditional Chinese culture. In a time before Neo-Confucianism and figures such as Zhu Xi (1130–1200), Buddhism had begun to flourish in China during the Northern and Southern Dynasties, and became the dominant ideology during the prosperous Tang. Buddhist monasteries played an integral role in Chinese society, providing accommodation for travelers in remote areas, schools for children across the country, and a venue for urban literature to host social events and gatherings such as farewell parties. Buddhist monasteries also they were involved in the economy, as their land holdings and serfs gave them enough income to establish mills, oil presses, and other businesses. Although the monasteries retained 'serfs,' these dependents of the monastery they could own property and employ others to help them in their work, including their own slaves.

Buddhism's prominent status in Chinese culture began to decline as dynasty and central government declined as well at the end of the century VIII to IX century. Buddhist nunneries and temples that were formerly exempt from state taxes were taxed by the state. In 845, Emperor Wuzong of Tang finally closed down 4,600 Buddhist monasteries along with 40,000 temples and shrines, forcing 260,000 Buddhist monks and nuns to return to secular life; this episode would later be called one of the Four Buddhist Persecutions. in China. Although the ban would be lifted only a few years later, Buddhism never regained its dominant status in Chinese culture. This development also came about through a new revival of interest in native Chinese philosophies such as Confucianism and the taoism. Han Yu (786–824), declared by Arthur F. Wright to be a "brilliant polemicist and ardent xenophobe", was one of the first Tang men to denounce Buddhism. Although his contemporaries found him rude and unpleasant, it would herald the later persecution of Buddhism in the Tang, as well as a revival of Confucian theory with the rise of Song dynasty Neo-Confucianism. Chán Buddhism, however, gained popularity among the educated elite. There were also many monks. Famous Chán of the Tang era, such as Mazu Daoyi, Baizhang and Huangbo Xiyun. The sect of Pure Land Buddhism started by the Chinese monk Huiyuan (334–416) was also as popular as Chán Buddhism during the Tang.

Buddhism rivaled Taoism, a system of native Chinese philosophical and religious beliefs that found its roots in the book of Daodejing (attributed to a 19th-century figure VI BC called Laozi) and the Zhuangzi. The ruling Li family of the Tang dynasty actually claimed descent from ancient Laozi. On numerous occasions where Tang princes would become crown princes or Tang princesses taking vows as Taoist priestesses, their luxurious old mansions would become abbeys. Taoists and places of worship. Many Taoists associated themselves with alchemy in their quests to find an elixir of immortality and a means of creating gold from invented mixtures of many other elements. Although they never achieved their goals in any of these pursuits useless, they contributed to the discovery of new metal alloys, porcelain products, and new dyes. Historian Joseph Needham called the work of Taoist alchemists "protoscience rather than pseudoscience." The connection between Taoism and alchemy, which some Sinologists have claimed, is refuted by Nathan Sivin, who claims that alchemy was just as (if not more) prominent in the secular sphere and more often practiced by laymen.

The Tang dynasty also officially recognized several foreign religions. The Assyrian Church of the East, also known as the Nestorian Church or the Eastern Church in China, received recognition from the Tang court. In 781, the Nestorian Stele was created to honor the achievements of their community in China. A Christian monastery was established in Shaanxi province, where the Daqin Pagoda still stands, and inside the pagoda are Christian-themed artworks. Although the religion largely died out after the Tang, it was revived in China after the Mongol invasions of the 13th century.

Although the Sogdians had been responsible for transmitting Buddhism to China from India during the 2nd to 4th centuries, they largely converted to Zoroastrianism shortly thereafter due to their ties to Sassanid Persia. Sogdian merchants and their families living in cities such as Chang'an, Luoyang and Xiangyang usually built a Zoroastrian temple once their local communities grew to over 100 households. Sogdians were also responsible for spreading Manichaeism in Tang China and the Uyghur Khanate. The Uyghurs built the first Manichaean monastery in China in 768, but in 843 the Tang government ordered the property of all Manichaean monasteries to be confiscated in response to the outbreak of war with the Uyghurs. With the blanket ban on foreign religions two years later, Manichaeism was driven underground and never flourished in China again.

Leisure

Much more than in earlier periods, the Tang era was famous for the time set aside for leisure activity, especially for those in the upper classes. During the Tang many outdoor sports and activities were enjoyed, such as shooting archery, hunting, horse polo, cuju football, cockfighting, and even tug of war. Government officials were granted vacations during their tenure. Officials had 30 days off every three years to visit their parents if they lived 1,600 km away, or 15 days off if the parents lived more than 269 km away (travel time not included). To the officials they were granted nine days of vacation for the weddings of a son or daughter, and five, three, or one days/day off for the weddings of close relatives (travel time was not included). Officials also received a total of three days off for the rite of passage of his son's coronation into manhood, and one day off for the rite of passage ceremony for the son of a close relative.

Traditional Chinese holidays such as Chinese New Year, Lantern Festival, Buffet Festival and others were universal holidays. In the capital city of Chang'an there was always a lively celebration, especially for the Lantern Festival, as the city's nighttime curfew was lifted by the government for three days in a row. Between 628 and 758, the imperial throne granted a total of sixty-nine great carnivals throughout the country, granted by the emperor in case of special circumstances such as important military victories, abundant harvests after a long drought or famine, the granting of amnesties, the delivery of a new crown prince, etc. For a special celebration in the Tang era, gigantic and lavish banquets were sometimes prepared, as the imperial court had contracted agencies to prepare the meals. This included a feast prepared for 1,100 elders of Chang'an in 664, a party for 3,500 officers of the Divine Strategy Army in 768, and a party for 1,200 palace women and members of the imperial family in 826. Drinking wine and alcoholic beverages were entrenched in Chinese culture, as people drank at almost all social events. A court official in the 8th century it supposedly had a serpentine-shaped structure called the 'Ale Grotto' built with 50,000 bricks on the ground floor, each with a container from which his friends could drink.

Dress Status

In general, clothing was made of silk, wool, or linen, depending on your social status and what you could afford. In addition, there were laws that specified what types of clothing could be worn by whom. The color of the clothing also indicated rank. "Officials over third grade wore purple clothing; those of more than fifth degree of light red color; those of more than fifth degree of dark green color; those of sixth grade and those of more than dark green; light green was only for those above seventh grade; dark cyan was exclusive to civil servants above eighth grade; Light cyan garments adorned officials above the ninth grade. Common people and all those who did not reside in the palace were allowed to wear yellow-colored clothing". During this period, China's power, culture, economy, and influence prospered. As a result, women could afford to wear loose-fitting, wide-sleeved clothing. Even lower-class women's robes would have sleeves four to five feet wide.

Woman's position

Concepts of social rights and the social status of women during the Tang era were remarkably liberal-minded for the period. However, this was largely reserved for urban women with elite status, as men and women in the rural countryside worked hard at their different tasks; wives and daughters were responsible for household chores such as weaving textiles and raising silkworms, while men tended to farm in the fields.

There were many women in the Tang era who gained access to religious authority by taking vows as Taoist priestesses. The chief mistresses of the brothels in the North Hamlet (red light district) of the capital Chang'an acquired large amounts of wealth and power. Her upper-class courtesans, who probably influenced Japanese geishas, were highly respected. These courtesans were known as great singers and poets, oversaw banquets and parties, knew the rules of all drinking games, and were trained to have the most respectable table manners.

Though renowned for their courtly demeanor, courtesans were known to dominate the conversation among elite men, and they weren't afraid to openly punish or criticize prominent male guests who talked too much or too loudly, bragged too much about their accomplishments or somehow ruined everyone's dinner with their rude behavior (on one occasion a courtesan even punched a drunken man who had insulted her). By singing to entertain the guests, the courtesans not only composed the lyrics to their own songs, but popularized a new form of lyrical verse by singing lines written by various famous and famous men in Chinese history.

It was fashionable for women to be full-figured (or plump). Men enjoyed the presence of assertive and active women. The foreign horse-riding sport of polo from Persia became a very popular trend among the Chinese elite, and women often played the sport (as portrayed by ceramic figures of the time). The preferred hairstyle for women was to comb their hair like "an elaborate building on the forehead," while wealthy women wore extravagant headdresses, combs, pearl necklaces, powders for the face and perfumes. In 671 a law was passed that tried to force women to wear hats with veils again to promote decency, but these laws were ignored as some women began to wear caps and not even hats, as well as men's riding clothes and boots and tight-sleeved bodices.

There were some prominent court women after the era of Empress Wu, such as Yang Guifei (719-756), who had Emperor Xuanzong appoint many of her relatives and cronies to important ministerial and martial posts.

Gastronomy

During the early Northern and Southern Dynasties (420–589), and perhaps even earlier, drinking tea (Camellia sinensis) became popular in southern China. Tea was then seen as a tasteful pleasure drink and also for pharmacological purposes. During the Tang dynasty, tea became synonymous with all that was sophisticated in society. The poet Lu Tong (790–835) devoted most of his poetry to his love of tea. The 8th century author, Lu Yu (known as the Sage of Tea), even wrote a treatise on the art of drinking tea, called The Tea Classic. Although wrapping paper had been used in China since the II century a. During the Tang dynasty, the Chinese used wrapping paper as folded and sewn square bags to hold and preserve the flavor of tea leaves. In fact, the paper found many other uses besides writing and wrapping during the it was Tang.

Previously, the first recorded use of toilet paper was made in 589 by the academic officer Yan Zhitui (531–591), and in 851 a Muslim Arab traveler commented on how he believed the Tang-era Chinese were careless with cleanliness because they did not wash with water (as was the custom of their people) when going to the bathroom; instead, he said, the Chinese simply used paper to clean themselves.

In ancient times, the Chinese had outlined the five most basic foods known as the five grains: sesame, legumes, wheat, panicle millet, and gluten millet. Ming dynasty encyclopedist Song Yingxing (1587–1666) He noted that rice had not been counted among the five grains since the time of the legendary, deified Chinese sage Shennong (who Yingxing wrote's existence was 'an uncertain matter') in the two millennia BCE. C., because the adequately wet and humid climate in southern China for growing rice was not yet fully settled or cultivated by the Chinese. But Song Yingxing also noted that in the Ming Dynasty, seven-tenths of the food for civilians was rice. In fact, by the Tang dynasty rice was not only the most important staple food in southern China, but had also become popular in the north, long central China.