Tamerlane

Tamerlane (from Persian: Timür-i lang, 'Timur the Lame', Tamorlane, Timur Lang, from the Turkish Timur Lenk, Timur or Temür, presumed to have been born in Kesh, Transoxiana, 9 April 1336 [25 Ša'bān, 736] - Otrar, on his way to China, February 17, 1405 [17 Ša'bān, 807]) was a Turco-Mongol conqueror, military leader and politician, the last of the great nomadic conquerors of Central Asia. Tamerlane founded the Timurid Empire in and around present-day Afghanistan, Iran, and Central Asia, becoming the first ruler of the Timurid dynasty. An undefeated commander, he is considered one of the greatest military and tactical leaders in history, as well as one of the most brutal. Tamerlane is also considered a great patron of art and architecture, having associated with intellectuals such as Ibn Khaldun, Hafez or Hafiz-i Abru, and his reign ushered in the Timurid Renaissance.

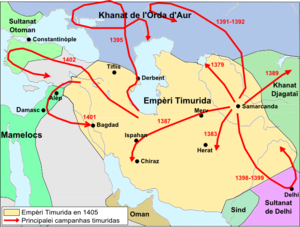

In little more than two decades, this Muslim nobleman of Turkic and Mongolian origin conquered eight million square kilometers of Eurasia. Between 1382 and 1405, his great armies crossed the Eurasian continent from Delhi to Moscow, from the Tian Shan range from Central Asia to the Taurus Mountains of Anatolia, conquering, reconquering, razing some cities and sparing others. His fame spread throughout Europe, where for centuries he was a terrifying fictional figure. For some peoples, more directly affected by his conquests, his memory, seven centuries later, is still fresh, either as the destroyer of cities in the Middle East, or as the last great leader of nomadic power.

Born into the nomadic confederation of Barlas in Transoxiana (present-day Uzbekistan) on April 9, 1336, Tamerlane had seized control of the western Chagatai Khanate by 1370. From that base, he led military campaigns across western Asia, southern and central Caucasus, and southern Russia, defeating in the process the khans of the Golden Horde, the Mamluks of Egypt and Syria, the emerging Ottoman Empire, and the late Delhi Sultanate of India, and becoming the most powerful ruler in the Islamic world. From these conquests, he founded the Timurid Empire, but this empire fragmented shortly after his death.

Tamerlane was the last of the great nomadic conquerors of the Eurasian steppe, and his empire laid the foundation for the rise of the more structured and enduring Islamic gunpowder empires (i.e., the Ottoman, Safavid, and Mughal empires)., in the 16th and centuries XVII.Tamerlane was of both Turkic and Mongol descent and, while probably not a direct descendant of either, shared a common ancestor with Genghis Khan on his father's side,although some authors they have suggested that his mother might have been a descendant of the Khan. It was clear that he intended to invoke the legacy of Chinggis Khan's conquests during his lifetime.Tamerlane envisioned the restoration of the Mongol Empire and, according to Gérard Chaliand, considered himself Chinggis Khan's heir.

According to Beatrice Forbes Manz, "in his formal correspondence, Tamerlane continued throughout his life to present himself as the restorer of Chingisid rights." He justified his Iranian, Mamluk, and Ottoman campaigns as reimposing legitimate Mongol control over lands seized by usurpers'. To legitimize his conquests, Tamerlane relied on Islamic symbols and language, referring to himself as the «Sword of Islam». He was a patron of educational and religious institutions. He converted almost all of the Borjigin leaders to Islam during his lifetime. Tamerlane decisively defeated the Christian Knights Hospitaller at the siege of Smyrna, calling himself a ghazi. By the end of his reign, Tamerlane had gained complete control over all remnants of the Chagatai Khanate, the Ilkhanate and the Golden Horde, and even tried to restore the Yuan dynasty in China.

Tamerlane's armies were multi-ethnic and feared in Asia, Africa, and Europe, sizeable parts of which his campaigns devastated. Scholars estimate that his military campaigns caused the deaths of 17 million people, representing approximately 5% of the world's population at the time. Of all the areas he conquered, Khwarazm suffered the most from his expeditions., since he rose several times against him.

Tamerlane was the grandfather of the Timurid sultan, astronomer and mathematician Ulugh Beg, who ruled Central Asia from 1411 to 1449, and the great-great-grandfather of Babur (1483-1530), founder of the Mughal Empire, which then ruled almost the entire Indian subcontinent.

Biography

Rise to power

A process of accumulating power very similar to that carried out a century and a half ago by Genghis Khan first (1361) allowed him to gain control over his tribe, the Barlas; and then (1370), alternately in alliance and in conflict with Amīr Husayn, gaining power over the ullus Chagatai (the confederation of tribes corresponding to the khanate of the descendants of Chagatai, second son of Genghis Khan).

The base of his power established, he invests Soyurghatmish as khan. It should be noted that Tamerlane did not belong to the family of the descendants of the Great Khan and the tradition of the Mongol Empire, accepted by all the nomadic tribes of Central Asia, required that only the descendants of Genghis could bear the title of khan and exercise sovereignty. Therefore, Tamerlane never assumed a royal title and, despite his enormous power and the autocratic nature of his control, he scrupulously respected this restriction, using simply the title amīr (commander), sometimes decorated with the adjectives buzurg or kalān (big). To bolster his position, he always posed as a loyal holder of the Genghisid line, appointing puppet khans and ruling in his name. He subsequently acquired the title of güregen (royal son-in-law) by marrying a princess of the dynastic line. In any case, he became the alleged genetic heir of Genghis Khan.

Consolidated at the helm of the ulus, he began his long series of conquests. Between 1370 (772) and 1372 (773) he made two campaigns to Moghulistan (territory north of the Tian Shan mountains, between the Balkhash and Issyk-Kul lakes), securing control of the rich Fergana valley. In the following two years, he undertakes a campaign against the Sufi dynasty of Corasmia. Until 1380 he was mainly concerned with consolidating his power in Corasmia (in 1380 he destroyed the city of Urgench for the first time) and Moghulistan. These campaigns were interspersed with almost permanent conflicts with the White and Blue Horde whose territory extended to the north of the Sir Darya River, provoked in part because Tamerlane had given refuge to Toqtamish, pretender to the throne of that horde. In April 1381 he takes Herat (present-day Afghan territory) and ends up imposing his direct power over the region at the end of 1383. He continues south, conquering Sistan and taking Kandahar; he turns to the west and in 1384-85 undertakes it against Amīr Walī in Mazandarán (south of the Caspian Sea, present-day Iran): he takes Astarabad and places supportive rulers in Tabriz and Sultaniyya, to return to Samarkand in 1385.

Large campaigns

In the winter of 1385-86 (787), his former ally and protégé Toqtamish raids and sacks Tabriz. This triggers a three-year campaign in Iran beginning in the spring of 1386 (788), in which he recovers Tabriz. In November 1387 (Dhū & # 39; l Qa & # 39; da 789), his troops put down a revolt in Isfahan, massacring the population. Meanwhile, Toqtamish had again attacked the Caucasus early in 1387; Tamerlane sends troops that defeat him, after which they then carry out a campaign against the Kara Koyunlu, and invade Kurdistan. In 1387-8 (late 789) Toqtamish attacks and sacks Transoxiana, so Tamerlane returns to the region and drives it back beyond the northern border between the winter and spring of 1388-9 (790-1).

While conducting a couple of new campaigns against Mogulistan (1389, 1390) (791, 792), controlled by Khidr Khwīaja, he prepares his armies for a final offensive against Toqtamish, who now leads the Golden Horde. He winters in Tashkent in 1390-91 (792), and on June 18, 1391 (15 Rajab, 793) defeats Toqtamish at the Kondurchá (Qundurcha or Jundurcha) river, north of Samara. Secured control of the area, and having placed under his direct rule most of the areas under his influence (in 1391-92 (794) appointing his grandson Pīr Muhammad b. Jahāngīr governor of Kabul), prepares a great campaign towards the Southwest.

On August 5, 1392 (15 Ramadān 794), he crossed the Amu Darya River (formerly known as Oxus) to begin his five-year campaign, where he defeated the Muzzafarids in April 1393 (795), conquering Fars and securing control of western Iran. All the survivors of the Muzzafarid dynasty will be executed shortly. [citation needed ] Four months later he takes Baghdad, defeating Sultan Ahmad of the Yalayerid Dynasty. He sends emissaries to the two Turkmen dynasties of western Iran and Anatolia, the Ak Koyunlu and the Kara Koyunlu, suggesting that they show submission, then attacking them and seizing most of their territories in the northern Tigris and Euphrates region..

While the troops continue the campaign in the Mesopotamian region, in the winter of 1395 (797) Toqtamish has again attacked in the Caucasus. Tamerlane organizes a campaign against him and defeats him at the Terek River on April 15, 1395 (23 Jumādā II, 797). With Toqtamish's forces overwhelmed, Tamerlane advanced to Moscow, looting along the way and returning via Darband in the spring of 1396 (798). The Golden Horde will never fully recover from this blow, and Toqtamish, stripped of his throne, will cease to be a threat. Tamerlane slowly returns to Samarkand, taking advantage of his passage to punish insubordinate rulers.

He stayed for a time in Samarkand receiving foreign ambassadors while promoting the construction of palaces and gardens. But in the spring of 1398 (800), he set out again, this time towards India. In December 1398 (Rabī & # 39; II, 801), he arrives in Delhi, which is looted and burned. After this, and after a brief campaign along the Ganges, he returned to Samarkand in the spring of 1399 (801).

After a brief stay in Samarkand, news reaches him that Amīrānshāh, the governor of western Iran, has gone rogue. Thus, Tamerlane will set out again at the beginning of the autumn of 1399 (802), for his longest expedition: the so-called "seven-year campaign". In the course of this campaign, he re-assured control over Georgia, which had been invaded several times by his empire, and recaptured Baghdad (which had been retaken by Ahmad), destroying it and massacring its inhabitants. He continued his offensive to the west, campaigning in Syria. against the Mamluks and in Anatolia against the Ottomans who had given refuge to the Qara Yusuf, the Kara Koyunlu and Ahmad. This offensive does not appear to be aimed at annexing territory, but rather as a show of force. For this reason, the Syrian campaign was brief; Timurid troops capture several large cities, including Aleppo, Damascus, and Himş (present-day Homs). Aleppo submits without a fight and is spared, but Damascus resists and is sacked and its inhabitants massacred.[citation needed]

In the spring of 1402, he attacked the Ottomans and defeated them near Ankara, taking Sultan Bāyāzīd I prisoner, who, although he was well treated by his captors, died a few months later. After raiding Anatolian cities, collecting ransoms, Timür was satisfied with the blow dealt to Ottoman hegemony and returned to Samarkand in the spring of 1404 (806) leaving no permanent administration in Anatolia. As he passed through Mazandaran, he put down a serious rebellion led by his former subject Iskandar Shayki.

The final stage

In Samarkand, Tamerlane carries out a great kurultái, justified by the election of a new puppet khan to succeed Muhmād Qan b. Soyurghatmish, died 1402 (805). He is attended by numerous embassies, including that of China and that of Ruy González de Clavijo, sent by Enrique III of Castile. After a few months in the capital, he begins preparations for his greatest feat: a campaign against China. He assembles a huge army and large amounts of supplies, and in the late autumn of 1404 (807) he sets out for Otrar, where he planned to winter. There he would die on February 17, 1405 (807) due to illness.

His body was returned to Samarkand and buried in the Gur-e Amir mausoleum. His remains are in the crypt, along with those of his grandson, Ulugh Beg, and other members of his family. The exact spot is marked by a large Mongolian nephrite tombstone with the following inscription: "If I rose from my grave, the whole world would tremble." A Soviet archaeological team headed by Mikhail Gerasimov (М. М. Герасимов) exhumed his body on June 22, 1941. Reconstructing his skeleton, it was found that, indeed, he was lame, unusually tall and stocky for his time (1.72 m tall) and it was also discovered that he had red hair. The studies Conducted by the Soviets determined that he possessed mixed Mongoloid and Caucasian features.

Regarding the supposed curse that protected the eternal rest of Tamerlane, it should be noted as an anecdotal fact that the date of his exhumation coincides with the beginning of the invasion of the USSR by Nazi Germany.

Wives and concubines

Tamerlane had forty-three wives and concubines, all of these women were also his consorts. Tamerlane made dozens of women his wives and concubines while he conquered the lands of his fathers or his former husbands.

- Turmish Agha, mother of Jahangir Mirza, Jahanshah Mirza and Aka Begi;

- Oljay Turkhan Agha (m. 1357/58), daughter of Amir Mashlah and granddaughter of Amir Qazaghan;

- Saray Mulk Khanum (m. 1367), widow of Amir Husain and daughter of Qazan Khan;

- Islam Agha (m. 1367), widow of Amir Husain and daughter of Amir Bayan Salduz;

- Ulus Agha (m. 1367), widow of Amir Husain and daughter of Amir Khizr Yasuri;

- Dilshad Agha (m. 1374), daughter of Shams ed-Din and his wife Bujan Agha;

- Touman Agha (m. 1377), daughter of Amir Musa and his wife Arzu Mulk Agha, daughter of Amir Bayezid Jalayir;

- Chulpán Mulk Agha, daughter of Haji Beg of Jetah;

- Tukal Khanum (m. 1397), daughter of Mongol Khan Khizr Khawaja Oglan;

- Tolun Agha, concubine and mother of Umar Shaikh Mirza I;

- Mengli Agha, concubine and mother of Miran Shah;

- Toghay Turkhan Agha, Mrs. Kara Khitai, widow of Amir Husain and mother of Shahruj;

- Tughdi Bey Agha, daughter of Aq Sufi Qongirat;

- Sultan Aray Agha, a Nukuz lady;

- Malikanshah Agha, a lady Filuni;

- Khand Malik Agha, mother of Ibrahim Mirza;

- Sultan Agha, mother of a child who died in childhood.

His other wives and concubines were: Dawlat Tarkan Agha, Burhan Agha, Jani Beg Agha, Tini Beg Agha, Durr Sultan Agha, Munduz Agha, Bakht Sultan Agha, Nowruz Agha, Jahan Bakht Agha, Nigar Agha, Ruhparwar Agha, Dil Beg Agha, Dilshad Agha, Murad Beg-Agha, Piruzbakht Agha, Khoshkeldi Agha, Dilkhosh Agha, Barat Bey Agha, Sevinch Malik Agha, Arzú Bey Agha, Yadgar Sultan Agha, Khudadad Agha, Bakht Nigar Agha, Qutlu Bey Agha, and other Nigar Agha.

Historical assessment

He was a politician and strategist capable of winning and maintaining the loyalty of his nomadic followers, operating within and changing a fluid political structure, and leading a massive army to unparalleled conquests. And while these abilities may stem from the subtleties of tribal political power struggles that precede most nomadic conquests, he also proved uniquely apt to rule over the Arab and Persian lands he conquered. Although he punished recalcitrant cities and imposed ruinous ransoms on cities that submitted to him without a fight, he showed a clear understanding of the value of trade and agriculture and took steps to promote them, using his troops to restore the areas and cities they had razed.. He was also skilled in manipulating established cultural symbols using them in the construction of public buildings to show his greatness, and religion to justify his conquests and his rule.

He could not read or write, and yet the histories of his time account for his knowledge of medicine, astronomy, and the history of the Arabs, Persians, and Turks. While the histories of his court chroniclers can be expected to paint a favorable picture of his intellectual abilities, these can be corroborated by at least one independent source: the autobiography of Ibn Khaldun, who encountered Tamerlane after the siege of Damascus in 1400- 1, and which highlighted his remarkable intelligence and his fondness for argumentation.

Despite the extraordinary power he attained, he failed to establish a government structure that would survive him. In part, this was due to his own policy of not delegating responsibilities to his descendants (the Timurids) or his military commanders, justified by the need to avoid the rise of potential rivals. On his death, his grandson and his chosen successor, Pīr Muhammad b. Jahāngīr, was unable to hold his own against the challenges of other princes, and none of Tamerlane's descendants achieved the complete loyalty of even his own troops. The resulting war of succession was unusually long and destructive, leading to a politically and economically weak dynasty.

Personality

Tamerlane is considered a military genius and brilliant tactician with an uncanny ability to work within a highly fluid political structure to gain and maintain a loyal following of nomads during his rule in Central Asia. He was also considered extraordinarily intelligent, not only intuitively but also intellectually. In Samarkand and his many travels, Tamerlane, under the guidance of distinguished scholars, was able to learn the Persian, Mongolian, and Turkish languages (according to Ahmad ibn Arabshah, Tamerlane could not speak Arabic). According to John Joseph Saunders, Tamerlane was "the product of an Islamized and Iranized society," and not a nomad from the steppe. More importantly, Tamerlán characterized himself as an opportunist. Taking advantage of his Turco-Mongol heritage, Tamerlane frequently used the Islamic religion or Sharia law, fiqh, and the traditions of the Mongol Empire to achieve his national military or political objectives.

Tamerlane was a learned king and enjoyed the company of the learned; he was tolerant and generous with them. He was a contemporary of the Persian poet Hafiz, and one story of their meeting explains that Tamerlane summoned Hafiz, who had written a ghazal with the following verse:

For the black mole on your cheek,

I would give the cities of Samarkand and Bukhara.

Tamerlane rebuked him for this verse and said: "With the blows of my well-tempered sword I have conquered most of the world to enlarge Samarkand and Bukhara, my capitals and residences; and you, lamentable creature, would exchange these two cities for a mole." Hafiz, undaunted, replied: "It is by similar generosity that I have been reduced, you see, to my present state of poverty." The king is reported to have been pleased by the witty reply and the poet departed with magnificent gifts.

The persistent nature of Tamerlane's character is said to have emerged after a failed raid on a nearby village, believed to have taken place in the early stages of his illustrious life. Legend has it that Tamerlane, wounded by an enemy arrow, found refuge in the abandoned ruins of an ancient fortress in the desert. Lamenting his fate, Tamerlane saw a small ant crawling a grain up the side of a collapsed wall. Thinking that the end was near, Tamerlane directed all his attention to that ant and observed how disturbed by the wind or the size of its cargo, the ant fell back to the ground every time it climbed the wall. Tamerlane counted a total of 69 attempts and finally, on the 70th attempt, the little ant succeeded and made its way to the nest with a precious prize. If an ant can persevere like that, thought Tamerlane, surely a man can do the same.

There is a shared opinion that Tamerlane's real motive for his campaigns was his imperialist ambition. However, the following words of Tamerlane: "The whole extent of the inhabited part of the world is not large enough to have two kings" explains that his true desire was to "wow the world." and, through his destructive campaigns, to make an impression rather than achieve lasting results. This is supported by the fact that, apart from Iran, Tamerlane simply plundered the states he invaded for the purpose of enriching his native Samarkand and neglected the conquered areas, which may have resulted in a relatively rapid disintegration of his Empire after his death.

Tamerlane often used Persian expressions in his conversations, and his motto was the Persian phrase rāstī rustī (راستی رستی meaning "truth is security" or " veritas salus"). He is credited with inventing the Tamerlane chess variant, which is played on a 10×11 board.

Tamerlane in the arts

- Christopher Marlowe wrote in 1587 Tamerlan the great and after the success of this, in 1588, he wrote The second part of the bloody conquests of the powerful Tamerlan.

- Georg Friedrich Händel dedicated an opera, Tamerlanopremiered in 1724.

- Edgar Allan Poe wrote in 1827 the poem Tamerlan.

- Jorge Luis Borges wrote in 1972 the poem Tamerlan (1336-1405), published in his book The gold of tigers.

- Marco Denevi wrote in 1970 the story The Great Tamerlan of Persia, published in his book Fun park.

- Enrique Serrano López wrote in 2003 the historical novel Tamerlan

Contenido relacionado

Flag of the savior

Hijra

Maus