Tacit

Gaius or Publius Cornelius Tacitus (c. 55-c. 120) was a Roman politician and historian of the Flavian and Antonine era. He wrote several historical, biographical and ethnographic works, among which the Annals and the Histories stand out.

Biography

Little is known about the biography of Cornelius Tacitus; not even the dates and places of his birth and death or his first name or his praenomen are known, although those of Gaius and Publius have been attributed to him without sufficient evidence. Most of the references to his life that are possessed of him have been drawn from his correspondence with Pliny the Younger or from his own works.

Timeline and origin

His date of birth is conjectured from the information given by Pliny in Letters, 7.20 when he highlights the exceptional friendship that unites them and the parallelism of their activities, informing in turn how he he was a young man when Tacitus was already famous. Hence it has been deduced that they are contemporary, although Tacitus must have been somewhat older. And since the date of Pliny's birth in the year 61 or 62 is known, the date of Tacitus's birth can be estimated around the year 55. As for the date of his death, it is assumed that, if as was his purpose he arrived in his old age to record the empire of Trajan, he had to die already in Hadrian's time, so it would be around the year 120.

Sometimes it has been claimed that he was born in Interamnum, in Umbria (now Terni). The basis of this hypothesis is that Marco Claudio Tacitus, the ephemeral emperor who ruled for a few months between 275 and 276, was born there and claimed to be a descendant of the historian. Other hypotheses, based on the origin of some of his close friends, make him originally from northern Italy or even from the province of Gallia Narbonense; nothing conclusive, in short. However, an anecdote that Pliny narrates suggests that his origins were not Italic, but provincial.

It is believed that his family was of equestrian origin, since he is related to a Cornelius Tacitus of that social class who is mentioned by Pliny the Elder (7.76) as a procurator in Belgian Gaul. Due to his age, this could not be the historian, but his father or his uncle could be.

Political career

Around 77 he began his political career, which would have been very regular. He himself tells that he started it with Vespasian and was successively favored by Titus and Domitian.

In the year 78 he married the daughter of Gnaeus Julius Agrícola, the governor of Britannia, to whom he would dedicate a monograph after his death. Being emperor Domitian, in the year 88, he was praetor and fifteenth century responsible for the cult and in that same year he participated in the celebration of the Ludi Saeculares. In the year 93 Agrícola died when Tácito and his wife were absent from the city and as Tácito affirms that the absence lasted four years, some think that he held some administrative position in the provinces, around which several unsound conjectures have been made..

He was consul suffectus in the year 97 under Nerva to replace the consul Lucio Verginio Rufo, who died during his tenure, whose funeral commendation he was in charge of pronouncing; Later, in 112-113, already under the rule of Trajan, he was proconsul, that is, governor of the province of Asia, according to an inscription found in Mylasa (Turkey).

Speaker and historian

His dedication to oratory soon earned him a high reputation thanks to his eloquence; he had been trained in contact with the best lawyers of his time, as he himself stated in his Dialogue on Speakers, 2, that in his youth he had listened with a passion typical of age, and both in public and private, to Marco Apro and Julio Segundo, luminaries of the forum at that time. There has been no shortage of those who think about the possibility that, in the same way as Pliny the Younger, he could have been a student of Quintilian, but there is no data that allows us to assure it, although there is no doubt that the features of the Dialogue..., very different from those that he himself cultivated in his historical works, correspond to the thought and style of the great rhetor, whose influence, together with that of Cicero, is unquestionable. But Tacitus's authorship of this work has been disputed.

He did not devote himself to history until after the year 97, when the death of Domitian allowed him to express himself without fear. And this application to the genre in his maturity, after completing an important civil career, as well as the fact that his political ideology is the foundation of his work, bring him closer to the profile of some republican historians such as César or Sallust. For a nobleman there were several ways to serve the State: political activity and the militia fundamentally and, once these activities were carried out, it was beneficial to provide other types of services, such as explaining the events and situations that Rome had gone through. It was what Salustio affirmed (Guerra de Catilina, 3): «It is beautiful to do well with the State, however it is not without sense to speak well of it as well. It is lawful to come to prominence in war and in peace." The virtus, the set of characteristics that make a man good, during war is based on value. In peace, writing history can also be a manifestation of that same virtus. Tacitus, by his thought and biography, largely agrees with these traits.

Work

No speeches by Tacitus have been preserved, so it is impossible to know his qualities in the field of rhetoric. There are some indirect references. Regarding the funeral speech in honor of Verginio Rufus that has been quoted above, Pliny the Younger ( Letters , 2.1.6) affirmed that the fact that Tacitus had praised him very eloquently filled the fortune of the deceased. On the other hand, in the time of Trajan he was entrusted with Pliny the Younger the accusation for concussion against Mario Prisco, who had been proconsul of Africa. In a session of the Senate presided over by Trajan, in the performance of his third consulship, he delivered a speech that was not only eloquent but also solemn (Pliny, Letters , 2.11.17).

Major works

The Stories

The Historiæ (Histories) narrate the period from the beginning of Galba's second consulate (69) to the death of Domitian (96). The term historiæ designates the historiographical work that recounts events of a more or less long period that ends in the times in which the author himself lives. Since the just and flourishing reigns of Nerva and Trajan, times "when it is allowed to think what you want and say what you think" (Historiæ, 1.1), Tacitus is encouraged to review an ominous age full of infamy We know that Tacitus worked on them during the first decade of the second century.

They probably consisted of fourteen books. The first four and about half of the fifth have been preserved. They have their origin in the second consulate of Galba (January 1, 69), during which year the empire passes through the hands of three emperors, Galba, Otto and Vitellius, until the military victory of Vespasian stabilizes the situation with the inauguration of the Flavian dynasty. What is preserved ends with Titus's campaigns against Jerusalem.

These early books seem to contain the thought base of the entire work. He fixes his attention on the attempt to renew freedom after the death of Nero, but does not allow himself to be swept away by optimism when judging the attitude of the legions. It is not possible to think that they took sides to turn their generals into emperors out of pure and disinterested love of freedom, but rather out of more material and bastard desires. It presents the political influence of Nero's court in the events that followed his death and the determination of certain characters not to lose privileged situations. He highlights the blindness and cruelty of the civil struggle this year, to the point that the sanctity of the Capitol was violated, which ended up being destroyed at the hands of citizens.

Vespasian brought order to that fateful year of the four emperors. Tacitus reveals how, behind the Flavian propaganda, which justified his assault on power under the title of love for the country, an enormous desire for power is actually hidden. The author is well aware that the center of gravity of Roman power has already shifted outside the city and that "a prince could be made anywhere other than Rome" (Histories, 1.4.2). All this thanks to the fact that the legions were more inclined to serve their bosses, if they gave them the opportunity to obtain benefits, than to selflessly assume the tasks of defending the state. On the other hand, in the provinces a feeling for power and a certain desire for freedom aroused. Tácito tries to unmask the leading personalities of politics and their motives to find the real causes of events.

The Annals

The Annals have as their full title Ab Excessu divi Augusti Historiarum Libri (Books of stories since the death of the divine Augustus). Saint Jerome writes of Tacitus that he "recounted the lives of the Caesars in thirty books from Augustus to Domitian." From this it follows that the two fundamental works, Annales and Historiæ, formed a seamless sequence. If the Historiæ covered from Galba to Domitian, the 16 books of the Annales collect the history immediately before, from the death of Augustus to that of Nero. But it should not be forgotten that these are two different works in their planning and development. In Annales 16 books cover 54 years, while the 14 of Historiæ had served to record only 27. It is evident, then, that the narration is much more detailed in the Annales i>Historiæ, perhaps due to the closer proximity of the facts that are dealt with in them. It is significant that in them the first four books are dedicated to a single year, 1968, although it is quite true that the density of events experienced in it required the use of a much larger scale than would be required at other times.

As always, the very little data we have is very imprecise. There is a passage in the work itself that gives a clue. In 2.61 mention is made of "...the Roman empire, which now extends to the Red Sea", where by this name it is to be understood that it refers to the Persian Gulf. From this data it could be inferred that the Annals began to be written immediately after the conquest of Mesopotamia in the year 114. The work would already be finished in Hadrian's time, close to the writer's death.

Of the Annals the first four books are preserved, the beginning of the fifth, the sixth, with the exception of its beginning, and then books XI to XVI with gaps at the beginning and end. The first six are dedicated to the reign of Tiberius. The second preserved part includes the reigns of Claudius from the year 47 and of Nero until 66.

As a historiographical genre, the Annals were characterized by referring to events far removed from the time lived by their author. The facts were available annually, hence its name. Although the Annals of Tacitus are organized in this way, they transcend the analistic genre, since they consider much broader views, related to the causes and effects of events and the influence of character traits on them. and the passions of its protagonists. In this sense, they have a lot of biography, since the psychological portrait occupies an important space in the work. The first part contains a superb—and tendentious—portrait of Tiberius. In the final part, the characters of Nero and Agrippina compete for power and create a situation in which men like Lucio Anneo Seneca no longer fit, who with his Stoic doctrines had contributed so much to temper the behavior of the emperor.

Minor works

Dialogue about the speakers

The Dialogus de oratoribus (Dialogue on Speakers), despite pronouncements against it by some scholars, is generally accepted as the work of Tacitus. It is Ciceronian in its conception and style, which is adapted here to the genre and is very different from that used by the author in historical works. The subject dealt with in it is the decline of oratory, which Quintilian had also raised in a lost writing entitled De causis corruptæ eloquentiæ (On the causes of the corruption of oratory).

At the beginning of the play, at the house of Curiacio Materno, a poet, two other characters appear with him: the orator Marco Apro, and Vipstano Mesala, an expert in rhetoric. The action is clearly located (chapter 17) in the year 75. This date is the term post quem for the dating of the work. There are those who tend to consider from this data that the Dialogue... is a work of youth a few years later. However, due to its stylistic and content relationships with Quintilian's Institutiones oratoriæ and with Trajan's Panegyric, there is no shortage of those who opt for a later dating from the early years of the 2nd century.

Maternal argues with Apro about the primacy of poetry over oratory. Then the discussion focuses exclusively on oratory. Apro defends modernity and ensures that the orators of his time do not have to make concessions to the old style of republican oratory, because times have changed. Messala, on the other hand, believes in the enduring value of Cicero and his contemporaries. According to him, at present oratory is in decline because of the abandonment of the study of old orators in the education of young people.

The dialogue ends with an intervention by Materno, the poet, who settles the issue with a correct historical criterion: it is the difference in political regime that determines the decline of oratory. In the Republic, a more agitated time, eloquence was necessary to pursue a political career and gain support in public activities. Since Rome lives in a long peace and stability thanks to the rule of the emperors, good orators are not needed. It cannot be guaranteed that this was the point of view of Tacitus himself, but if it were, it would be expressed at the same time with a good dose of irony and prudence so as not to irritate the emperor. What is said between the lines is that without a free political regime oratory loses its function.

Life of Julio Agrícola

De vita Iulii Agricolæ (On the life of Julio Agrícola), also known by the abbreviated title Agrícola, is his first work with historical content. Tacitus associates in it the biography and the historical monograph. The biographical part in the strict sense occupies the first chapters only. Two thirds of the work are dedicated to the military campaigns and the government of Agrícola in Britain, probably the most important of the protagonist's achievements. It also devotes some attention to the ethnography and geography of the country.

The work was written after the death of Agrícola at the age of 53. For this reason, it follows to a large extent the tradition of the traditional funeral eulogy (laudatio funebris) pronounced by a relative at the burial of prominent figures according to Roman tradition. It places its emphasis on Agrícola's personal behaviors and actions that fit within the framework of the old aristocratic virtus.

Tacitus does not limit himself to dealing with the life, qualities and exploits of his father-in-law. He is always present in his own thought, so he gives us a reflection of himself. He also devotes his attention to what the terrible period of Domitian's rule meant, whose ignominies he highlights. The end of the work (chap. 43), in which Tacitus, although he does not subscribe to it, echoes the rumor according to which the cause of Agricola's death had been a poisoning that could be attributed to Domitian, serves to complete the perverse image of the emperor.

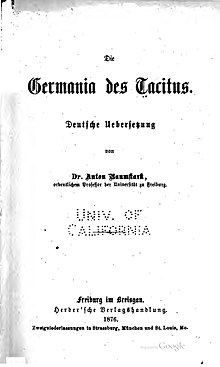

Origin and territory of the Germans

De origine et situ Germanorum (On the Origin and Territory of the Germans), also known as Germania, describes the Germans and his country. The monograph had to be written very soon after the first year of Trajan's reign (98), which was also the year of his second consulship, since Tacitus uses this date as a reference to calculate how much time had elapsed since the first attacks of the Cimbri..

The work is generally very objective. Of his literary sources, Tacitus only mentions Caesar, but Pliny the Elder and other historians and geographers must be added. In addition to the literary information, Tacitus, who is not known to have had direct knowledge of the peoples who inhabited Germany, must have compiled the oral narrations of soldiers, merchants, and travelers returning from the other side of the Rhine. to the global study of the Germans: physical geography, institutions, private and daily life, military aspects, etc. Then, in more detail, the peculiarities of each ethnic group are described separately. But not everything is objectivity in the work.

Tacitus does not renounce reflecting his personal vision of the Germans and their relations with Rome. His intention is to show how virtues that once prevailed in Rome continued to be cultivated among those. He believed he recognized in them the old values of austerity, dignity, and military valor that the Romans had once possessed, but had diminished in later times. Tacitus views with sympathy certain characteristics of these peoples: their primitivism, proximity to nature, purity and rusticity. The comparison with the Rome of the moment is always present, explicitly or implicitly. And old Rome does not fare well for its decadent spirit. However, it should not be thought that the author professes an uncritical admiration for the Germans: he is aware of their main defects, such as their love of drinking and gambling, their tendency to be inactive in times of peace, and their tremendous military indiscipline..

He also saw how the Germans constituted a real danger to Rome, whose moral deterioration made it incapable of an effective defense. Their warrior virtues made them superior to the Roman armies, concerned on many occasions with interests that had nothing to do with the defense of the empire. Thus, in chapter 37, where he deals with the Cimbri, he reviews all the setbacks that Rome had suffered because of her since the first attacks in 113 B.C. C. He does not hesitate to express his admiration for them when he describes them as a "small people, but enormous for their glory": the people defeated several times, but never subdued.

Method and philosophy of history

Tacitus is rigorous in the use of documentation. He collects the information provided by previous historians (Aufidio Baso, Cluvio Rufo, Pliny the Elder, Fabio Rústico and others), memories of characters (those of Agrippina, for example) and oral testimonies; he also resorted to the Acta diuturna populi Romani ( Chronicles of the Roman People ), which constituted a kind of official newspaper of Rome, and to the senate archives. Although he tries to use his sources impartially, his strong personality ends up prevailing, so subjectivity triumphs. The philosophical (especially Stoic) and ideological components always end up coloring what he narrates. But at the beginning of his Stories he declares what is his guide:

- «The truth was altered in many ways, in the first place by disregard of the State, to which they felt as if they were alien; then by the desire to flatter or, on the contrary, by hatred against the powerful. And so, between enemies and subjected, no one cares about posterity» (Hist. I, 1)

Almost all of his work is dominated by the effort to highlight the infamies committed by most of the emperors from the death of Augustus to that of Domitian. This resource serves to further highlight the merits of Nerva and Trajan. Tacitus is not a good connoisseur of the military, the administration or the economy. In his political career, in fact he was never entrusted with military activities. For this reason the study of him is uneven: he is interested above all in the psychological and dramatic aspects, and deals with the imperial court, which offers rich material for moral analysis.

His political philosophy is wavering. He is hesitant to choose between the ancient Roman notion of the oligarchic senatorial state, led by "the best," and the Hellenistic idea of a state ruled by a monarch. All in all, his stoic tendencies seem to lead him to distrust the moral solidity of a political model based on the decisions (and, therefore, the arbitrariness) of a single man. On numerous occasions he seems to long for the old republic and its concept of freedom, although his pronouncements in this sense are camouflaged as necessary so as not to be annoying to the imperial regime.

Style

It is characteristic of Tacitus the extreme care of the style. His language is steely, brief in construction, very synthetic, given to brachylogy. He flees from carefully organized periods and looks for asymmetry. All of this makes his expression very dense, of a conceptual baroque style in which the sharpness of the idea prevails over any ornamental trend. He does not hesitate to use neologisms. His main stylistic model is Sallustio, although, contrary to what that of him did, he avoids any trace of archaism: quite the contrary, his artistic intention is channeled into a conscious search for modernity. The aforementioned features of Tacitus's language sometimes lead him to a type of narration with large and loose brushstrokes, where the reader's imagination is stimulated to fill in for what is not explicit.

Tacito considers that the holders of power are the protagonists of history. Consequently he gives great importance to the portrait, in which he highlights the psychological and moral components. For example, the portrait of Tiberius contained in the first part of the Annals is extremely powerful. Tacitus has been able to impose, sometimes over and above the facts themselves, the character's vision of him.

He always tries to create a dramatic climate, for which he uses individual human actions and chance events. Although he tries to document himself and in general respects the facts, his interest always tends to create powerful images, in which he imposes his own convictions. He does not hesitate to achieve the desired effect by reproducing rumors that he himself assures that he has not verified. Although he establishes a doubt about certain data, the simple fact of mentioning them is influencing the reader, whose position is shaped according to the author's intentions. The image, then, is installed above rational arguments and remains. For example, the one that transmitted the burning of Rome, the conduct of Nero and the subsequent persecution of Christians (Annals, 15.44) has created the most deeply rooted iconography for these events: the one that has been installed in the literature and cinema. Tacitus does not entertain himself in proving the perversity of Nero: a few tremendous brush strokes are enough, only half a page, to cover him with opprobrium.

Studies and historical reception

Tacitus has been described as the "greatest historian the Roman world has ever produced". His work has been valued for its moral teachings, dramatic narrative, and style. In addition to the area of history, Tacitus's influence he is most prominent in the area of political theory. The political lessons of his works can be classified in two ways: the "Red Tacitists" use his work to support republican ideals and "black Tacitists"; they read it as a lesson in Machiavellian realpolitik.

Although his work is our most reliable source on the history of his era, the accuracy of the events he describes is occasionally questioned. The Annals are based partly on secondary sources, and there are some obvious errors, for example the confusion of the two daughters of Mark Antony and Octavia Minor, both called Antonia. However, the Histories are written on the basis of primary documents and intimate knowledge of the Flavian period, and are therefore believed to be more accurate.

Spanish translations

Apart from the unpublished and partial translation of the Historias by Antonio de Toledo (1590), among the ancient translators of Tacitus into Spanish, the first was the Flemish gentleman, of Portuguese origin, Emanuel Sueyro (The works of Caio Cornelio Tácito, Antwerp: by the heirs of Pedro Bellero, 1613, reprinted in Madrid: Viuda de Alonso Martín, 1614 and 1619). Then Baltasar Álamos de Barrientos ( Spanish Tacitus illustrated with aphorisms , 1614) translated all of his works, accompanying them with comments on difficult passages; his version was already finished, though not printed, in 1594; Later was the highly praised and widespread, reprinted even today, by Carlos Coloma (1629). Many others were less extensive or occasional, for example, that of The first five books of the Annales of Cornelius Tacitus: which begin from the end of the Empire of Augustus until the death of Tiberius... (Madrid, 1615) by Antonio de Herrera y Tordesillas or, by Juan Alfonso de Lancina, Political Commentaries on the Anales de Tacito (Madrid, 1687). Diego Clemencín published Ensayo de traduccións... (Madrid: Benito Cano, 1798) which includes the Germania, the Vida de Agrícola and some fragments de Tácito with a preliminary speech, in all of which José Mor de Fuentes helped him (although he claimed after Clemencín's death that most of the translations were his, without the problem being elucidated to date). Marcelino Menéndez Pelayo wrote about the quality of these versions in the prologue of his edition of the Anales (1890) for the Biblioteca Clásica (pp. 96-97):

- Without being perfect the work of Coloma, and departing, as far apart, from the austere concision and sequedad sentenciosa of the original Latin, whose defect is to have modernized to the continuous phrases and customs, deserves with all that the preference, for the conditions of style, among all the other Castilian translations of Tácito. It is a work that is read without difficulty and even with delight; not small merit in translations. Barrientos, though rich and abundant in the tongue, is much more diffuse and amplifier than Coloma. Sueyro, much harder and lacking fluidity. As for Herrera (Antonio), Lancina, Clemencín and Mor de Fuentes, they have only left translations of some books of the Anales or the Germania and AgriculturalEven in this they deserve little loa. There is therefore no more useful translation than that of Coloma, adding by counting the two writings that he stopped translating, and that we will take from Alamos, following the employment of the editors of the last century and the modern Classical Library of Barcelona

In 1957 Editorial Aguilar printed in Spanish the Complete Works of Tácito (directed by V. Blanco García). In 1979 and 1980, Editorial Gredos published the translation of the Anales (books I-XVI) by José Luis Moralejo Álvarez (reissued in 2001), also author of a translation of the Historias published by Akal in 1990.

Eponymy

- The lunar crater Tacitus bears this name in his memory.

- The asteroid (3097) Tacitus also commemorates its name.

Contenido relacionado

1931

Newfoundland and labrador

Carl Sagan