Syphilis

Syphilis, formerly called Gallic morbidity, French disease or bubas, is an infectious disease of Chronic, transmitted mainly by sexual contact, produced by the spirochete Treponema pallidum, subspecies pallidum (pronounced pál lidum). Its clinical manifestations are of fluctuating characteristics and intensity, appearing and disappearing at different stages of the disease: ulcers on the sexual organs and red spots on the body. It produces lesions in the nervous system and in the circulatory system. It exists throughout the world and has been described for centuries.

Etymology

The name "syphilis" was coined by the Veronese poet and surgeon Girolamo Fracastoro in his Latin poem Syphilis sive morbus gallicus ('Syphilis or the French disease') in 1531. The protagonist of the work is about a shepherd named Syphilus (perhaps a variant of Sipylus, a character from Ovid's Metamorphoses), who tended the flocks of King Alcihtous. Annoyed with the Greek god Apollo, since he burned the trees and consumed the sprouts that fed the sheep, he decided not to worship him but the king. In retaliation, Apollo punished him along with the entire kingdom, afflicting them with a horrible disease, which he named "syphilis" after the shepherd. Adding the suffix -is to the root Syphilus, Fracastoro created the new name for the disease, and included it in his medical book De contagonibus ('On contagious diseases', Venice, 1584).

In this text, Fracastoro records that at the time, in Italy and Germany, syphilis was known as the «French morbidity», and in France, as «the Italian morbidity».

Denominations in disuse

Syphilis has also been known as avariosis, búa, buba (or bubas), gallic, lues venerea, or mal de bubas.

Deprecated names

The different names used between the 15th and 17th centuries give an idea of the vast extent of the disease, and of the custom of blaming neighboring countries for it.

- In Italy, Germany and the United Kingdom it has been called "French sickness".

- In France, since the epidemic in the French army in the Italian wars, he was called "Napolitan evil or Neapolitan disease".

- In Russia, "polaca disease".

- In Poland, "German disease".

- In Japan of the Sengoku Period, “Chinese Memorb”

- In the Netherlands, Portugal and North Africa, "Spanish sickness" or "Phinestone sickness".

- In Turkey, "Christian sickness".

- In Spain, “Portuguese evil”, or “Gallic morb” (“French evil”).

History

The origin and antiquity of syphilis represent one of the most important unresolved controversies in the history of medicine. The fundamental questions of this controversy are: Did syphilis reach the Old World from the New World through the crew of Christopher Columbus —as the first epidemic of this disease in Europe seems to indicate in 1493? Or, did syphilis originate in the Old World and remain an unidentified disease until the late 15th century Was it noted for increased virulence or transmissibility? In relation to this controversy, two hypotheses of the origin of syphilis have been elaborated, which generate debate in the field of anthropology and historiography.

Pre-Columbian hypothesis

The pre-Columbian hypothesis maintains that the treponematoses, including syphilis, are a group of variants of a disease that spread both in the Old and in the New World. In Europe its manifestations would have been confused with leprosy. According to this hypothesis, the pinta appeared in Africa and Asia around 15,000 BC. C., with a natural animal reservoir. Yaws would have developed as a consequence of pinta mutations around the 10th millennium BC. C. spreading throughout the world except in America that was isolated. Endemic syphilis emerged from yaws around the 7th millennium BC. C. as a consequence of climatic changes (appearance of arid climate). Around the XXX century BCE. C. sexually transmitted syphilis appeared in Southwest Asia due to the low temperatures of the postglacial era, and from there it spread to Europe and the rest of the world. Since then it has undergone various mutations and clinical manifestations, the clinical form being "venereal", predominant in the 15th century, probably accentuated by the reincorporation of strains from America.

The epidemiology of the first presentation of syphilis in the late 15th century does not define whether the disease was new or arose from an earlier disease.

Lesions on Neolithic-age skeletons are due to syphilis. Even in skeletons from 2000 B.C. C. in Russia, with pathognomonic bone lesions. Although such lesions can be confused with lepromatous lesions. Perhaps Hippocrates has described the symptoms of syphilis in the tertiary stage of it.

Also in the ruins of Pompeii (which was buried in the year 79 by the Vesuvius volcano) skeletons have been found with signs that could be of congenital syphilis.

According to scientific work from the University of Bradford (United Kingdom) made public in June 1999, in a cemetery of an Augustinian abbey in the port of Kingston upon Hull (north-east England) used between 1119 and 1539, 245 skeletons were found, of which three had clear signs of syphilis. C14 dating indicated that the male with the most obvious signs of syphilis had died between 1300 and 1450.

Some scientists think that syphilis may have been introduced to America after contacts between Vikings. In October 2010, an excavation of skeletons carried out in Great Britain provided new support for this hypothesis, as examinations experts indicated that the disease was known in this country two centuries before the voyage of Christopher Columbus.

Unitary hypothesis

This hypothesis, which some consider a variant of the pre-Columbian hypothesis, maintains that all treponematoses correspond to a single original disease, developed very anciently, perhaps in the Upper Paleolithic in sub-Saharan Africa, and that it spread from there and ever since globally, its variations being the consequence of geographical and climatic differences. In other words, pinta, yaws, syphilis, and other treponematoses are adaptive responses of T. pallidum to environmental differences. There is evidence of the existence of treponematoses on practically all continents in pre-Columbian times. In America, the manifestations of treponematosis in pre-Columbian times were venereal syphilis, in a temperate climate (South America), and yaws, in a tropical climate (Caribbean). This hypothesis indicates that yaws may have spread from West Africa to the Iberian Peninsula in connection with the black African slave trade, 50 years before Christopher Columbus' voyage. Yaws, endemic in Africa at the time, manifested itself in Europe in various forms, one of them being venereal syphilis, that is, sexually transmitted.

Columbian or Columbian exchange hypothesis

This hypothesis maintains that syphilis was a sexually transmitted disease (STD) from the New World that the crew of Christopher Columbus would have brought to Europe. It was elaborated by Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo and Ruy Díaz de Isla, two Spanish doctors present at the time of the return of Christopher Columbus from America, in 1493.

Fernández de Oviedo (1478-1557), in his short Summary of the Natural History of the Indies (1526) says:

(...) The first time that this disease was seen in Spain was after Admiral Christopher Columbus discovered the Indies and returned to these parts, and some Christians who came with him to find themselves in that discovery and those who made the second journey, who were more, brought this plague, and from them he beat other people (...) because in no way he beats himself as from the council of man to woman (...) and the Christians who give themselves to the conversation and council of the Indians, few must escape this danger.

Another chronicler of the Indies who considered the same thesis was Francisco López de Gómara (1511-1566):

That the Buddhas came from the Indies. The ones of this Spanish island are all bubous, and as the Spaniards slept with the Indians, they hinchiéronse after bubas, a very sticky disease that torments with repeated pains. Feeling tormented and not improving, many of them returned to Spain for healing, and others for business, which stuck their covert ailment to many courteous women, and they to many men who went to Italy to the war of Naples in favor of King Ferdinand the Second against French, and they hit that evil there. Finally, they were beaten to the French; and as it was at the same time, they thought that they were beaten with Italians, and they called him a Neapolitan evil. The others called him a bad French man, thinking he'd hit him French. But there was also one who called him Spanish sarna.

Current proponents say pre-Columbian Native American skeletons are known to have syphilitic lesions and link the crew of Columbus's first voyage (1492) and the syphilis epidemic at the German siege of Naples (1494).

The Ecuadorian physician and historian Plutarco Naranjo criticizes the Columbian hypothesis developed by Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo and Ruy Díaz de Isla, stating that their observations are historical errors or fantasies, and that, on the contrary, syphilis arrived in America from Europe. According to this author, there were no personnel on the expeditions with sufficient medical knowledge to identify or recognize the different venereal diseases; likewise, Fernández de Oviedo lacked such knowledge and had not recognized patients in Europe or in the New World. Another observation made by Plutarco Naranjo is that the doctor Diego Álvarez de Chanca, who accompanied Christopher Columbus and described in great detail various diseases of both the sailors who accompanied them and the aborigines, did not mention any type of disease with manifestations cutaneous lesions suggesting a diagnosis of syphilis. Finally, this author notes the fact that syphilis continued to spread in the Old World while no epidemics occurred in the New.

Other opponents of this hypothesis have attempted to demonstrate the presence of syphilis in Europe prior to Columbus's voyage by dating European skeletons with evidence of syphilitic lesions before 1492, but the results have been inconclusive, and many of them their evidence has resulted in repeated and confirmed dating with an antiquity after 1492. There are still 16 European bones from before 1492 with lesions that could be of a syphilitic type, evidence that is not accepted by the adherents of this hypothesis, arguing that said dating is have altered and appear older, due to the consumption of food from the ocean that bring older organic material.

15th to 19th century

From Naples, the disease swept across Europe starting in 1495, with extremely high morbidity and mortality rates. As Jared Diamond describes it: "At that time, syphilis pustules frequently covered the body from head to knee, causing flesh to fall off people's faces, and killing within a few months." In addition, the disease was more frequently fatal than today. Diamond concludes that "by 1546 the disease would have evolved into syphilis with the symptoms known today."[citation needed]

The main cause of this pandemic (in Europe, much of Asia and North Africa) after the 16th century is thought to have been probably due to rapid urbanization.

At the time, mercury was believed to be the cure for syphilis. It was common to use it to treat skin problems. The treatment consisted of breathing the gas of the hot mercury.

Patients salivated uncontrollably, lost their teeth and lost their reason until a new remedy appeared in 1517: guaiac, a shrub found in Haiti. Supposedly, it was what the natives of the island used.

In the 18th century, thousands of Europeans contracted syphilis. In the 19th century, Flaubert, studying brothels from Egypt, found that the harlots without exception were all infected with syphilis.

The chronicles of the time blamed syphilis on the huge migrations of armies (in the time of Charles VIII, at the end of the century XV).

Some writers maintain that there was simultaneously an epidemic of gonorrhea, which was supposed to be the same disease as syphilis. Others say it was perhaps an epidemic of a concomitant but unknown disease.

Historically, it was a disease greatly feared by the wet nurses or foster care of the inclusives, since a newborn with congenital syphilis could go unnoticed and take several months to develop the disease. In this case, through small inadvertent oral or perioral lesions of the child, the disease could be transmitted to the nurse through erosions on the breast at the time of lactation.

20th century

In 1901 the German bacteriologist Paul Ehrlich synthesized Salvarsan, an organic compound of arsenic, specifically designed for the treatment of syphilis and which became one of the first effective synthetic drugs for the cure of infectious diseases. Salvarsan (and its derivative, Neosalvarsan) were abandoned after 1944, in favor of the much more effective antibiotic treatment with penicillin. To test penicillin, during the years 1946 to 1948 the United States carried out experiments on syphilis on citizens of Guatemala without the consent or knowledge of the men and women who were used as guinea pigs.

In 1905 Schaudinn and Hoffmann discovered the etiologic agent of the disease.

In 1906, August von Wassermann discovered a reaction named after him that diagnosed the disease from a blood test.

In 1913, Hideyo Noguchi ―a Japanese bacteriologist working at the Rockefeller Institute― demonstrated that the presence of the spirochete Treponema pallidum (in the brain of a patient with progressive paralysis) was the cause of syphilis.

In Spain, cases of syphilis have doubled in six years, from four cases per 100,000 inhabitants in 2006 to 7.8 in 2012.

Epidemiology

Syphilis is spread primarily through sexual contact, followed by transplacental transmission. Kissing, receiving blood transfusions or accidental inoculation are less important routes of transmission today. Couple studies have established transmission rates of 18 to 80%, while prospective studies give rates of 9 to 63%. Finally, the overall expected probability of transmission between partners is 60%.

Forms of contagion: Through skin contact with the secretion generated by the chancres, or by contact with the sick person's syphilitic nails; by performing oral sex without a condom (whether the chancres are in the mouth, on the penis, or on the vulva), or through kissing if there are syphilitic lesions in the mouth. It can be spread by sharing syringes. If the mother is infected she can transmit it to her children through the placenta (congenital syphilis) or through the birth canal (connatal syphilis). In both cases, the baby may die early or develop deafness, blindness, mental disturbances, paralysis, or deformities.

It is practically impossible for it to be transmitted by a blood transfusion, because the blood is analyzed before it is transfused, and because Treponema pallidum does not survive more than 48 hours in blood stored in the blood cell.

Endemic syphilis can be transmitted by nonsexual contact. But it is not transmitted by toilet seats, daily activities, bathtubs, or sharing utensils or clothing.

It is important to note that the subject in the early phase of the disease is highly contagious (the venereal ulcer is full of treponemes), but it is argued that after four years the infected individual cannot further spread the microorganism through sexual intercourse.

In relationships between a man and a woman, it is easier for the man to catch the virus. The period in which most people are infected is between 20 and 25 years of age. Recontagion is very common in homosexual men.

In the 1980s and 1990s, in Europe there was a relative decrease in syphilis cases, related to fear of HIV infection, which led to the widespread use of condoms, which represent an efficient barrier against infection, both from HIV such as Treponema pallidum.

According to WHO data, there are 12 million new cases of syphilis worldwide:

- Sub-Saharan Africa: 4,000 000

- South Asia and Pacific: 4 000

- Latin America and the Caribbean: 3 000 000

- North Africa and Middle East: 370 000

- Western Europe: 140 000

- Eastern Europe and Central Asia: 100,000

- North America: 100 000

- Australia and New Zealand: 10 000

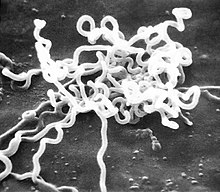

Etiology

The organism that causes syphilis is Treponema pallidum subsp pallidum. This microorganism is a mobile spiroform (spiral thread-shaped) bacterium belonging to the order Spirochaetales, family Spirochaetaceae, genus Treponema. Its diameter is from 0.10 to 0.18 micrometers and its length between 6 and 20 micrometers. The average number of spiral twists of a T. pallidum is from 6 to 14. Its mobility, like a corkscrew, is given by endoflagella, which allow it to rotate rapidly, twist and bend at angles.

This bacterium propagates by simple multiplication with transverse division. Unlike other bacteria in its family, it can only be cultivated in vitro for a short period, with a maximum survival of 7 days at 35 °C, in a particularly enriched medium and in the presence of CO2 due to its particular nutritional and metabolic requirements. Its vitality is maintained in liquid nitrogen, and it proliferates excellently in rabbit testicles.

In blood stored in the blood cell for transfusions, the bacteria survive between 24 and 48 hours.

Pathogenesis

Treponema pallidum can survive in a human host for several decades, since it presents a mechanism of resistance to the effector systems of the immune response by covering itself with host proteins to camouflage itself until it reaches the Central Nervous System.

Clinical picture

After an incubation period of between two and six weeks, syphilis goes through four clinical stages with diffuse borders: primary, secondary, latent and tertiary.

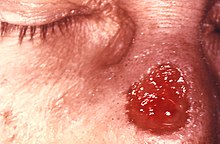

Primary syphilis

This stage is characterized by the presence at the site of inoculation—the mouth, penis, vagina, or anus—of a painless, indurating ulcer resembling an open wound, called a chancre. It is accompanied by inflammation of the regional nodes. In a few weeks the chancre heals spontaneously.

In men, chancres are usually located on the penis or inside the testicles, but also in the rectum, inside the mouth or on the external genitalia, while in women, the most frequent areas are: cervix and the greater or lesser genital lips.

During this stage it is easy to become infected with the secretion generated by the sores. A person infected during this stage can infect their partner by having unprotected sex.

Secondary syphilis

Secondary syphilis begins between the time the chancre disappears or up to six months later. It is characterized by general malaise, headache, low-grade fever, generalized adenopathies, painless pinkish papules called “syphilitic cloves” on the palms of the hands and soles of the feet, sometimes with scaling, lesions on the mucosa of the mouth or genitals, wart-like confluent lesions near the site of chancre formation (condyloma lata) and patchy hair loss. Syphilitic nails and mucosal lesions are highly contagious. Secondary syphilis can last for weeks or months.

Latent Syphilis

Latent syphilis is characterized by positive serology with no symptoms or signs. It is divided into two parts: early latent syphilis and late latent syphilis, depending on whether the time the disease has been present is less than or more than two years, respectively. If the time of illness is unknown, it is treated as late latent syphilis.

Tertiary Syphilis

In the third phase (also called the final phase), between one and twenty years after the onset of infection, syphilis reawakens to directly attack the nervous system or an organ.

In this phase the most serious problems occur and can even cause death. Some of the problems are:

- Ocular disorders.

- Cardiopathies.

- Brain injuries.

- Spinal cord injuries.

- Loss of coordination of the limbs.

- Syphilic or luetic aneurysm.

- Syphilytic goma or syphilome.

Although treatment with penicillin can kill the bacteria, the damage it has done to the body may be irreversible.

Congenital Syphilis

Babies of women with syphilis can become infected through the placenta or during delivery. Most newborns with congenital syphilis have no symptoms, although in some cases a rash may develop on the palms of the hands and soles of the feet. Later symptoms include deafness, tooth deformities, and saddle nose (when the nasal bridge collapses).

Diagnosis

Before the advent of serological tests, accurate diagnosis was impossible. In fact, she was called "the great imitator" since -in the primary and secondary phase- her symptoms can easily be confused with those of other diseases, causing the subject to downplay it and not go to the doctor.

Treatment

In the past it was treated with mercury, making the phrase "a night with Venus and a life with Mercury" famous, but this treatment was more toxic than beneficial.

The treatment of choice to treat syphilis is penicillin, in all its phases. In the primary and secondary phases, benzathine penicillin G is used at a dose of 2.4 million IU once intramuscularly. In the late and late latent phases, benzathine penicillin G is used in three doses of 2.4 million IU intramuscularly once a week, totaling 7.2 million IU.

For neurosyphilis, treatment is crystalline penicillin G given intravenously at 18 to 24 million IU in one dose given as a slow continuous infusion or divided into 6 daily doses (one dose every two or three days). This last form of administration is carried out in order for the antibiotic to diffuse into the CSF (cerebrospinal fluid), the place where the bacteria are mainly housed during this last phase. However, the treatment does not ensure clinical efficacy.

In patients allergic to penicillin, an antibiotic regimen that does not contain beta-lactams is chosen, the most commonly used being doxycycline and ceftriaxone.

Treated on time, the disease is easily cured without leaving sequelae.

Having syphilis increases the risk of contracting other sexually transmitted diseases (such as HIV), since chancres are an easy route into the body.

If left untreated, it can cause:

- Ulcerations in the skin.

- Circulatory problems.

- Ceguera.

- Paralysis.

- Dementia.

- Neurological disorders.

- Death.

Having suffered from syphilis and having been cured does not imply immunity, since it can quickly be contracted again. This is because the bacterium that causes syphilis (Treponema pallidum) has only nine proteins in its coat, which is not enough for the human immune system to recognize it and produce antibodies against it. fight it or become immunized. [citation required]

A common reaction (10-35%) in the first 24 hours after treatment administration is the Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction, generally mild and self-limited. It can occur with all antibiotic treatments, but its highest incidence occurs with treatment with penicillin. Symptoms usually include fever, skin efflorescence, malaise, headache, and myalgias. The causes are supposed to be due to the release of cytokines, lipoproteins and immune complexes due to the massive destruction of the treponemes by the antibiotic and the corresponding immune reaction of the host. His treatment is based on antihistamines, paracetamol, good hydration and rest.

Reduce risk

Consistent and correct use of latex condoms for vaginal and anal sex can reduce the risk of transmission, but while the condom can protect the penis or vagina, it does not protect against contact with other areas such as the scrotum or anal area..

Diagnosis and tests

- Rapid Plasmatic Reagine Review (RPR).

- TPHA Treponema Pallidum).

- FTA-ABS exam.

- VDRL exam in RCR.

- serological test for syphilis (VDRL).

Experiments on syphilis in Guatemala (1946-1948)

During the years 1946 to 1948, experiments on syphilis were carried out in Guatemala as part of a program sponsored and executed by the United States government. They were experiments with humans in which doctors, generally Americans, infected without the consent of the victims ―numerous Guatemalans, soldiers, prisoners, psychiatric patients, prostitutes, and even orphaned children―, inoculating them with syphilis and other venereal diseases such as gonorrhea, to verify the effectiveness of new drugs, both antibiotics -especially penicillin-, as well as different preventive treatments.

Contenido relacionado

Human eye

The Wolf (1941 film)

Castile and Leon