Symphony No. 5 (Beethoven)

The Symphony No. 5 in C minor, op. 67, by Ludwig van Beethoven, was composed between 1804 and 1808. This symphony is one of the most popular and performed compositions in classical music. It consists of four movements: it begins with a sonata allegro, continues with an andante and ends with an uninterrupted scherzo, which comprises the last two parts. Since its premiere at the Theater an der Wien in Vienna on December 22, 1808, conducted by the composer, the work has acquired notorious prestige, which still continues today. E. T. A. Hoffmann described the symphony as "one of the greatest works of all time".

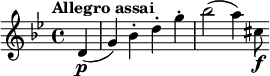

It begins with the distinctive four-note 'short-short-short-long' (ta-ta-ta-taa), repeated twice:

The symphony, and this motif in particular, are world-famous, appearing frequently in popular culture, with new interpretations in other genres, such as disco and rock and roll, as well as appearances in movies and on television.

History

Development

The Fifth Symphony had a long maturation process. The first sketches date from 1804 after having finished the Third Symphony. However, Beethoven had to interrupt his work on the Fifth to prepare other compositions, including the first version of Fidelio, the Piano Sonata Appassionata, the String Quartets Rasumovsky Op. 59, the Violin Concerto, the Piano Concerto No. 4, the Fourth Symphony and the Mass in C major. The final preparation of the Fifth Symphony, which took place between 1807 and 1808, was carried out in parallel with the Sixth Symphony, which were premiered at the same concert.

When Beethoven composed it, he was already reaching 40 years of age, his personal life was marked by the anguish caused by his increasing deafness; despite this, he had already entered into an unstoppable process of "creative fury". Europe was decisively marked by the Napoleonic Wars, the political turmoil in Austria, and the occupation of Vienna by Napoleon's troops in 1805.

Premiere

The work was premiered on December 22, 1808 at the Theater an der Wien in a monumental four-hour concert consisting exclusively of Beethoven premieres, and conducted by Beethoven himself. The two symphonies appeared in the programs named in reverse of the order by which we know them today: the Sixth was the first and the Fifth appeared in the second half. The program was:

- La Sixth Symphony, Op. 68

- The aria Oh, perfid! Op. 65

- The Glory of the Mass in do mayor Op. 86

- The Concert for piano n.o 4 Op. 58 (touched by Beethoven himself)

- (pause)

- La Fifth Symphony, Op. 67

- The Sanctus and Benedictus of the same Mass

- A piano improvisation only played by Beethoven

- La Coral fantasy, Op. 80

Premieres abroad

In Spain it premiered on the night of December 19, 1838, at the Teatro de Madrid, and a month later at the Liceo de Barcelona.

Edition and dedication

The work was published by Breitkopf & Härtel: the parts of the work in April 1809 and the score in 1820. The autograph score was donated in 1908 by the family of Felix Mendelssohn to the Prussian State Library (Preußische Staatsbibliothek) in Berlin where it is kept today (now Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin).

The work was commissioned by Count Franz von Oppersdorff in June 1807, pleased by the Symphony No. 4 which he had also commissioned. He paid her a total of 500 guilders, first an advance of 200 and the rest in November 1808, when Beethoven gave him the complete score, granting her exclusive use for six months. However, he dedicated the symphony to two of his patrons and friends, Prince Joseph Franz von Lobkowitz and then Count Andrey Razumovsky. Oppersdorff did not commission more works from Beethoven.

Reception and influence

There was little critical response to the premiere, which took place under adverse conditions. The orchestra did not play well, having only held a rehearsal before the concert, and in the Choral Fantasy, due to a mistake by one of the musicians, Beethoven had to stop the performance and start again. The auditorium was very cold and the length of the program ended up exhausting the public. However, a year and a half later, another run drew rave reviews from E.T.A. Hoffmann in the Allgemeine Musikalische Zeitung. He described the music with dramatic imagery:

Radiant lights are thrown into the deep night of this area, and then we warn in the gigantic shadows that, swinging forward and backward, approach us and destroy all that is within us except the anguish of the eternal longing—a longing that in every pleasure that arises in jubilious sounds ends up sinking and succumbing. Only through this pain, which, while consuming but not destroying love, hope and joy, tries to blow up our breasts with a total lament full of voices of all passions, and lives in us and we are captivated by the guardians of the spirits.

In an essay entitled Beethoven's Instrumental Music, written in 1813, E.T.A. Hoffmann further stressed the importance of the symphony:

Can there be any Beethoven work that confirms all this to a greater degree than its indescribably deep and magnificent symphony in lesser do? How this wonderful composition, in an endless climax, brings the listener compellingly to enter the world of infinite spirits!... There is no doubt that everything is precipitated as an ingenious rapsody according to many, but the soul of each reflective listener was surely moved, and very intimately, by a feeling that is no other than the indecent portentous longing, and even the final chord—in fact, even at the moment that follows him—that he will be unable to leave that wonderful spiritual world, where pain and joy embrace him in the form of sound. The internal structure of the movements, its execution, its instrumentation, the way in which one and the other are happening—everything between the themes generates unity—which only has the power to keep the listener firmly in an inner mood. This relationship is sometimes clear to the listener when he hears in the connection of two movements or discovers the fundamental bass in common, a deeper relationship than if not revealed in this way he speaks on other occasions only from mind to mind, and it is precisely this relationship that compellingly proclaims the free possession of a master genius.

The symphony soon became a centerpiece in the repertoire. As an emblem of classical music, the Fifth was played at the inaugural concerts of the New York Philharmonic Orchestra on December 7, 1842, and at the United States National Symphony Orchestra on November 2. of 1931. In Latin America, the inaugural concert of the National Symphony Orchestra of Peru in 1938 at the Municipal Theater of Lima, under the direction of Theo Buchwald included this work. Marking a turning point in both its technical and emotional impact, the Fifth has had a great influence on composers and music critics, and has inspired the work of such composers as Johannes Brahms, Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (particularly his Symphony No. 4), Anton Bruckner, Gustav Mahler and Hector Berlioz. The Fifth stands alongside the Third and Ninth symphonies as Beethoven's most revolutionary work.

Description

The symphony is scored for piccolo (4th movement solo), two flutes, two oboes, two clarinets in B ♭ and do, two bassoons, contrabassoon (solo in fourth movement), two horns in e ♭ and do, two trumpets, three trombones (alto, tenor and bass, solo in the fourth movement), timpani (in G and C) and strings.

The symphony lasts approximately 30 minutes and consists of four movements:

- Allegro with brio

- Walking with motorbike

- Scherzo. Allegro

- Allegro

Allegro con brio

The first movement begins with the four-note motif, one of the best known in classical music, which is played by all strings and clarinets in unison over a three-octave span, in five bars in all. There is considerable debate about how to interpret these measures, especially due to the presence of pilot whales on the fourth and eighth notes, and the silence at the beginning of each motif. Some conductors do it in the tempo of an allegro, others take the liberty of giving it more weight, in a much slower and heavier tempo, taking the tempo of the allegro afterwards.; others play them with a molto ritardando (gradually slowing down each of the four notes).

The first movement is written in sonata form, common in the first movements of classical symphonies. This musical form consists of four large parts: the exposition in which the main ideas grouped into the first and second themes appear, the development in which these ideas are contrasted and worked on with numerous resources, the restatement in which the themes reappear in a different way. different to reach the coda that ends the movement.

In the analytical aspect, this motif is the basis of the first theme of the exhibition, characterized by its relentless and vehement rhythmic force. Its tonal ambiguity is singular in it, since among the notes that sound, the one of the tonality of the movement does not appear, do, and although apparently we seem to be in the relative tonality of E flat major, the absence of harmonization generates an expectation and a tension that is resolved next, because in the next passage, the motive appears, clearly harmonized in C minor.

This energetic motif, presented twice initially, later takes shape on the strings, with free contrapuntal imitations. These imitations alternate with each other with such rhythmic regularity that they appear as a simple flowing melody, which becomes the main theme of the movement. The motif is treated dramatically, with sudden changes in intensity and sweeping crescendos. Its rhythmic contour is always present, which is why some speak of monothematism (development of a single theme) in this movement (and probably in the entire symphony).

After a rapid modulation to the relative major key, E flat major, a new theme appears, like a call, introduced by the horns, a melodic extension of the first theme. In this new key, the secondary theme appears, with a calmer rhythm (although the bass subtly reminds us of the first theme) and pastoral. Then the cadences announce the end of the exhibition, always with the rhythmic motif of the symphony. The development leads us through various tonalities and takes the drama to extremes. A passage stands out where chords of the strings and woodwind alternate, in a distant tonal region in a minor mode.

After a brief contrapuntal elaboration, the theme ends in a "Beethovenian moment of exhaustion", at which point the first theme reappears. Before the bridge that leads to the secondary theme, a very expressive and melancholic oboe solo is heard, in an almost improvisational style. A long coda ends the movement.

Andante with a motorcycle

This is a lyrical work in the form of double variations, which means that two themes are presented alternately and varied. After the variations there is a great coda. The selection of the key of A flat major after a movement in C minor was a common technique in Beethoven. He used it both in his Sonata & # 34;Patética & # 34; as in his Violin Sonata No. 6 Op. 30 No. 1.

The movement begins with the exposition of the first theme, a unison melody for violas and cellos, accompanied by double basses. Then follows a second theme, with the harmony given by the clarinets, bassoons, violins with an arpeggio in triplets in the violas and basses. A variation of the first theme appears. It is followed by a third theme, with violas, cellos, flute, oboe and bassoon followed by an interlude in which the entire orchestra participates in a fortissimo and a series of crescendos to close the movement.

Scherzo. Allegro

The third movement is in ternary form, consisting of a scherzo and a trio. It follows the traditional model of the symphonic 3rd movement of classicism, containing in sequence the main scherzo, a contrasting trio, the return of the scherzo, and a coda. (For further discussion of this form, see "Text Questions", below.)

The movement returns to the initial tonality do minor and begins with the following theme, played by cellos and counterbases:(![]() listen (?·i))

listen (?·i))

The musicologist of the centuryXIX Gustav Nottebohm was the first to notice that this theme has the same series of sounds (in different tones and range) as the main theme of the final movement of the famous Symphony n.o 40 K. 550 of Mozart. This is the theme of Mozart:

(![]() listen (?·i))

listen (?·i))

(The derivation highlights more clearly if one first hears the Mozart theme, then the Mozart theme transported to the tonality of Beethoven, and then the Beethoven theme:

(![]() listen (?·i)

listen (?·i)

While such resemblances sometimes occur accidentally, this does not exactly seem to be the case. Nottebohm discovered the resemblance when he was examining a notebook used by Beethoven while composing the Fifth Symphony : there, 29 bars of Mozart's finale appear, copied by Beethoven.

The initial theme is answered by another contrasting theme in the winds, and the sequence is repeated. Then the horns loudly announce the main theme of the movement, and the music develops from it.

The trio section is in C major and written in a contrapuntal texture. When the scherzo returns at the end, it is played by the pizzicato of the strings and very softly.

In the final coda, the music drops to a whisper before slowly building to a grand crescendo that transitions seamlessly into the fourth movement. This final passage takes us from C minor to C major of the finale. (Beethoven attempted a similar key change at the beginning of his Symphony No. 4.)

"The scherzo offers contrasts that are somewhat similar to those of the slow movement in that they derive from the extreme difference in character between scherzo and trio... The scherzo then contrasts this figure with the famous ' motto' (3 + 1) of the first movement, which gradually dominates the entire movement".

Allegro

Much has been written about this fourth movement, in which some musicologists see an interrelation with a popular children's tune of the time, A, B, C, die Katze lief im Schnee ('A, B, C, the cat ran through the snow'); it's a sound theory, given Beethoven's penchant for arranging popular songs. What everyone agrees on is that it is a perfect finishing touch to the symphony, a joyous finale that weaves together and culminates the work and whose alternating and growing measures still amaze with their brilliance, forcefulness and display of virtuosity that they demand.

The triumphant and exhilarating finale, with the air of a mighty march, begins without interruption after the scherzo. It is written in an unusual variant of sonata form: at the end of the development section, the music reaches a semi-cadence, in fortissimo, and the music continues after a pause with a new recapitulation of the scherzo horn theme. The recapitulation is then introduced by a crescendo in the last bars of the interpolated section of the scherzo, just as it was at the beginning of the final movement. The interruption of the finale with material from the scherzo was already used by Haydn, who did it in his Symphony No. 46 in B flat, of 1772. It is not known if Beethoven knew this composition.

The Fifth Symphony includes a very long coda, in which the main themes are sounded in an abbreviated form. Towards the end time speeds up towards a presto. The symphony ends with 29 bars of C major chords, played in fortissimo. Charles Rosen, in The Classical Style suggests that this ending reflects Beethoven's sense of classical proportions: the "incredibly long" cadenza with pure C major is necessary "to round off the extreme tension of this immense work".

Associated topics

Much has been written about the Fifth Symphony in books, popular articles, and program notes for concerts and recordings. This section summarizes some of the themes that frequently appear in these.

The “Fate” motif

The initial motif has sometimes been credited with the symbolic meaning of depicting "Fate knocking at the door." This idea comes from secretary and factotum Anton Felix Schindler who, many years after Beethoven's death, wrote:

- «The composer himself provided the key to these profound themes when one day, in the presence of the one he writes, he pointed out the beginning of the first movement and expressed with these words the fundamental idea of his work: “So fate touches the door!”».

Schindler's testimony regarding any passage in Beethoven's life is discredited by scholars (he is believed to have added lines in his conversation books). On the other hand, it is often commented that Schindler gave a highly romanticized opinion of the composer. Thus, although we cannot know if Schindler actually invented this quote, there is a strong probability that he did.

There is another story about the same motif; the version given here comes from Antony Hopkins's description of the symphony (see references below). Karl Czerny (Beethoven's student, who premiered the "Emperor" Concerto and famous author of piano studies) said that "the little musical pattern had come [to Beethoven] from the song of a match-scribe, who heard while walking through the Prater in Vienna. Hopkins then remarks that "given the choice between a matchstick and fate-knocking-at-the-door the public has preferred the more dramatic myth, though what Czerny tells us is far too unlikely to have been fabricated.".

Assessments surrounding these interpretations tend to be skeptical. «The popular legend that Beethoven thought up this magnificent exordium of the symphony to suggest “Fate knocking at the door” is apocryphal. Beethoven's student Ferdinand Ries was actually the author of this supposed poetic exegesis, which Beethoven received very sarcastically when Ries told him about it. Elizabeth Schwarm Glesner comments that "Beethoven was known to say almost anything 'important' to inquiring hangers-on"; this can be taken to contest both stories.

Beethoven's Key Selection

The key of the Fifth Symphony, C minor, is often considered a special key for Beethoven, specifically "a stormy and heroic key". Beethoven wrote in C minor several works whose character is quite similar to that of the Fifth Symphony. For a detailed discussion, see Beethoven and C minor.

Is the opening motif repeated throughout the symphony?

It is commonly asserted that the opening four-note rhythmic motif (short-short-short-long; see beginning) repeats through all movements of the symphony, unifying it. According to various web pages, "it is a rhythmic pattern (dit-dit-dit-dot*) that makes its appearance in each of the other three movements and thus contributes to the overall unity of the symphony"; a single motif that unifies the entire work"; "the key motif of the entire symphony"; "the rhythm of the famous opening figure... is repeated at crucial points in subsequent movements". The New Grove cautiously endorses this view, stating that "the famous opening motif will be heard in almost every measure of the first movement and, modifications being allowed, in the other movements."

There are several passages in the Symphony that have led to this view. The most frequently noticed occurs in the third movement, where the horns play the following solo in which the pattern c-c-c-l occurs several times:

In the second movement, an accompaniment line plays a similar rhythm: (listen)

In the finale, Doug Briscoe suggests that the motif can be heard in the piccolo part, probably referring to the following passage: (listen)

Later, in the coda at the end, the basses play the following several times: (listen)

On the other hand, there are critics who are not impressed by these similarities and consider them simply accidental. Antony Hopkins, discussing the theme of the scherzo, says that "no musician with the slightest discernment could confuse [the two rhythms]", explaining that the rhythm of the scherzo begins on a downbeat while the theme of the first movement begins on a downbeat. weak.

Donald Francis Tovey dismisses the idea that a rhythmic motif unifies the symphony: "This profound finding was supposed to reveal an unsuspected unity in the work, but it does not seem to have been carried far enough." Applied constantly, he continues, the same approach would lead to the conclusion that many other Beethoven works would also "be linked" to this Symphony, such as the motif that appears in the piano sonata "Appassionata", at the beginning of the Piano Concerto No. 4 (listen), and in String Quartet Op. 74. Tovey concludes: "The simple truth is that Beethoven could not do without just such purely rhythmic figures at that stage of his production."

To Tovey's objection may be added the prominence of the rhythmic figure c-c-c-l in earlier works by Beethoven's older contemporaries, including Haydn and Mozart. To give just two examples, we find it in Haydn's "Miracle" Symphony No. 96 (listen), and in Piano Concerto No. 25, K. 503 from Mozart. (hear). Such examples demonstrate that the rhythms "c-c-c-l" they were a regular part of the musical language of the composers of Beethoven's time.

It seems likely that the fact that Beethoven, either deliberately or not, or unconsciously, woven a single rhythmic motif through his fifth symphony (in Hopkins's words) "remains eternally open to debate".

Trombones and piccolos

Although it is very common to say that in the final movement of Beethoven's Fifth the trombone and piccolo were used for the first time in a symphony, that is not true. Swedish composer Joachim Nikolas Eggert required trombones for his Symphony No. 3 in E flat written in 1807, and examples of earlier symphonies with a piccolo part abound, including Symphony No..º 19 in C major by Michael Haydn composed in August 1773. On the other hand, the orchestra that was used in the opera at that time, already used these instruments, for example in the opera La Magic Flute by Mozart.

Text questions

The repetition in the third movement

In the autograph score (i.e., the original version in Beethoven's hand), the third movement has a repeat barline for the entire opening: when the scherzo and trio sections have played, it is indicated to the performers who must start over and play these two sections again. Then comes a third exposition of the scherzo, this time markedly different by the string pizzicatos and with a direct transition to the Finale (see above). Most modern printed editions of the score do not include this repeat bar; and most performances of the symphony play the movement as ABA' (where A = scherzo, B = trio, and A' = modified scherzo), in contrast to the ABABA' from the original (autograph) score.

It is unlikely that the repeat bar in the autograph is simply an error on the part of the composer. The ABABA' for the scherzi it appears other times in Beethoven, for example in the Bagatelle for piano, Op. 33, no. 7 (1802), and in the Fourth Symphonies, Sixth and Seventh. However, it is possible that for the Fifth Symphony, Beethoven originally preferred ABABA', but changed his mind in the course of publication in favor of ABA'.

Since Beethoven's time, published editions of the symphony have always been ABA'. However, in 1978, an edition that specified ABABA' It was prepared by Peter Gülke and published by Peters Publishing. In 1999, another edition by Jonathan Del Mar published by Bärenreiter advocated a return to ABA'. represents Beethoven's final intention; that is to say, that the conventional is the best.

In concert performances, the ABA' prevailed until very recent times. However, since the appearance of the Gülke edition, directors have felt more free to exercise their own decision. Artistic director Caroline Brown, in her notes to her recording of her performance of ABABA & # 39; with The Hannover Band directed by Roy Goodman, says about it:

The restoration of repetition certainly alters the structural emphasis normally evident in this symphony. Allows the scherzo to be a mere transitory passage of little weight, and, by making the listener more involved with his main motives, he makes the passage oblique in the bridge passage to the finale It seems more unexpected and extraordinary in its intensity.

The ABABA' they seem to be particularly favored by conductors who specialize in authentic performances (ie, with the original instruments from Beethoven's time). These include Brown, as well as Christopher Hogwood, John Eliot Gardiner, and Nikolaus Harnoncourt. The executions ABABA' on modern instruments they have also been recorded by the Zurich Tonhalle Orchestra conducted by David Zinman and by the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Claudio Abbado.

Reassign bassoon notes to horns

In the first movement, before the appearance of the second theme in the exposition, the following phrase is assigned by Beethoven in solo to a pair of horns:

In this part, the theme is in the key of E flat major. When the same theme is repeated later in the restatement section, it appears in C major. As Antony Hopkins warns:

This... represented a problem for Beethoven, because the tubes [of their time], were severely limited in the notes that they could really touch before the invention of valves, and could not touch the phrase in the 'new' tonality of greaterat least not without covering the bell with the hand and thus damping the sound. Therefore, Beethoven had to give the subject to a couple of fagotes, which, in their acute record, seemed to be a less than adequate substitute. In modern executions the 'heroic' implications of original thought were considered more dignified than the fact of preserving the second instrumentation; the phrase is touched on both occasions by the two tubes, which now by their current mechanical possibilities can be trusted with all security.

Indeed, ever since Hopkins wrote this passage (1981), conductors have really experimented with preserving Beethoven's original instrumentation for the bassoons. This can be heard on the version conducted by Caroline Brown mentioned in the preceding section, as well as on a recent recording by Simon Rattle with the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra. Although horns capable of playing the C major passage were developed only shortly after the premiere of the Fifth Symphony, we do not know whether Beethoven would have wanted to replace it with modern horns or to keep the bassoons. in this crucial passage.

There are powerful arguments in favor of keeping the original orchestration even when modern tube horns are available. The structure of the movement proposes a programmatic alteration of light and dark, represented by the major and minor modes. Thus, the heroic transition of the theme dispels the darkness of the first minor theme and brings the second theme into a major mode. However, in the development, Beethoven systematically fragments and dissects this heroic theme in measures 180 to 210. Therefore he may have rewrote his refrain in the recapitulation with a weaker key to hide the minor expository closing. Also, the horns used in the fourth movement are natural horns in C, which can easily play this passage. If the instruments were on stage, Beethoven could perhaps have written muta to C in the first movement, just as he did in his indication muta to F in bar 412 of the first movement. movement of his Third Symphony. However, the horns (in E flat) are playing just before this passage, so such a change would be very difficult, if not impossible, to make due to lack of time.