Swastika

The swastika or swastika (卐) and the swastika (卍 >) are a cross whose arms are bent at right angles:

- The swastika, in the dextrogy sense when it rotates in the sense of the needles of a watch (i.e., whose upper arm points to the right): s

- The sauvstic, in a levoirous sense when it turns in the opposite direction to the needles of a watch (i.e., whose upper arm points to the left):..

Geometrically, its 20 sides make it an irregular icosagon.

Also called the swastika, in various Eastern religions, including Hinduism, Buddhism and Jainism, the swastika is a very ancient spiritual symbol, associated with good luck. As a result of World War II and the Holocaust, in the West it is a symbol strongly associated with Nazism and anti-Semitism. However, in countries such as India, Nepal, Mongolia, China and Japan, the swastika lacks this connotation. It is common to see swastikas at the entrance to temples, shops and homes, as well as on vehicles and clothing, retaining its meaning as a spiritual symbol associated with good luck.

Etymology

The Spanish term «esvástica» comes from the Sanskrit language swastíka (in Devanagari: स्वस्तिक), which literally means 'very auspicious', but can also mean:

- Good.

- happily

- successful

- Good luck.

- "Let him go well!"

- Salud!

- Bye!

- So be it!

- form of greeting (especially at the beginning of a letter).

- form of approval or sanction.

- Suastí: ‘welcome, fortune, luck, success, prosperity’.

- his: ‘muy’ and

- Astí: ‘that exists’.

Origin and description

From about seven thousand years ago, the pre-Iranian herdsmen of Djowi and locations near Susa represented the swastika rotating to the left, presumably as a number, with the cross (+) being 10, X being 11, X beginning to turning 12 and finally the swastika turning 13 (5000 BC). The oldest archaeological object with a swastika dates from the 5th millennium BC. C. It was found in Samarra and it is a clay plate (mud) with female figures that form a swastika and scorpions (Parrot, 1963).

According to Sir Alexander Cunningham (quoted by Sir Monier William), it is a monogram generated by the conjunction of the letters su astí in ashoka characters (before the Devanagari script, which are the ones that They have been used for several centuries in the writing of Sanskrit). According to some authors this shows that the symbol was not created in this era, but approximately in the 5th century BC. C., and may even have been earlier. Although the Vishnuists say that the swastika is eternally drawn on one of the four hands of the god Vishnu.

This symbol, which has appeared repeatedly in the iconography, art and design produced throughout the history of humanity, has represented very diverse concepts. Among these are luck, Brahman, the Hindu concept of samsara (reincarnation) or Suria (god of the Sun), to name only the most representative. At first the swastika was used as a symbol among the Hindus. It is first mentioned in the Vedas (the sacred scriptures of the most primitive Hinduism), but its use is transferred to other religions of India, such as Buddhism and Jainism.

Other names

Other names in Spanish

- Cross ranged (in herald), since each arm resembles a Greek capital gamma letter (Interpreter). We also have that in French croix gamméein English fylfotin German Winkelmaßkreuzin Dutch hakenkruis and in Italian croce uncinata. Also, the term is used gammadion (de) gamma, third letter of the Greek alphabet.

- Crampon cross (in herald), since each arm resembles one of the pins of a crampon (in French: croix cramponnéein English: cramponned crossin German: Hakenkreuzin Italian: croce uncinatain Dutch: weerhakenkruisIn Hungarian: horogkereszt).

- Tetraskel is related to the Greek name tetraskelion (lit. “four legs”). Pre-Roma tetraskeles have been found (teasing dextrogiros y levógiros) en Vizcaya, en las estelas encontradodas en Arrieta, Forua y Busturia. In Busturia you have found a swastika levogira. It also has Galicia in castros, petroglyphs and other places. Here you can see two types together, respecting the shape of the Galician galaxy triskeles and the other, in circular form, much older, as the triple spirals that can also be seen in the British islands.

Other languages

- Swastika comes from the Sanskrit language (spoken in India), specifically from the word suasti, which means "welcome". The term is composed of the adverb his (“good” or “very”) and asti (third singular person of the verb asti [‘ello es’]). A literal translation would be "conductive to the good-being".

- Wan, in Chinese, it is related to the number 10,000 by lexical analogy. Swastika is used as a Chinese character more than the respective adaptations of wanzi ().). From Wan with the suffix zi (meaning ‘graph’) is derived manji ()) in Japanese and Handle (USD Self) in Korean.

There are also other symbols that have a certain resemblance to the swastika, such as the triskel or trinacria (from the Greek triskelion) used as an emblem of the Isle of Man or Sicily and recurring Celtic motif. Later on, the Basque lauburu, with curved arms, a modern revival of the Cantabrian lábaro, will also be visually reminiscent of the swastika.

In art and architecture

The swastika is a fairly common motif in modern Greco-Roman culture and Indian art, as well as in the architecture of the past, having been depicted in mosaics, friezes, and other works from the ancient world.

Similar symbols in classical Western architecture include the cross, the triskel (three bent legs joined at the top), and the Cantabrian labarum from northern Spain. The swastika also receives in this context the name gammadion (which comes from gamma, the third letter of the Greek alphabet).

In the art of China, Korea, and Japan, the swastika can often be found as a continually repeating motif (something distantly reminiscent of a fretwork pattern). One of these motifs, called sayagata in Japanese textile art, includes clockwise and counterclockwise swastikas that are joined by lines. Swasticoid symbols have been found abundantly in the ruins of Troy.

Already in the West, in Roman, Romanesque and Gothic art the swastika as an isolated figure is rarely found, but it is found more frequently as a repeating pattern in the decoration of edges or surfaces. Some of the tessellations on the floor of Amiens Cathedral feature interlocking or conjoined swastika motifs. Fringed borders of conjoined swastikas were common in Roman architecture and can also be seen on Neoclassical buildings.

In religion and mythology

In European Pagan Traditions

In certain European pagan traditions, the swastika, in its two modalities, right-handed and left-handed, is the symbol used to represent, respectively, the gates of birth and death.

In these traditions, the swastika is also located on the zodiacal wheel, in the signs of Pisces and Virgo, the former representing the gate of birth and the latter the gate of death. The axis traced by both signs divides the zodiacal wheel into two semicircles. The semicircle that goes from Pisces to Virgo (following the order of the signs) represents a life or incarnation, and the one that goes from Virgo to Pisces represents the transit or time between two lives. The entire zodiac wheel represents the eternal transition from one incarnation to the next or metempsychosis.

Hence, in this cyclical transit there are two doors to pass from one state to another: the door of birth and the door of death, represented by the right-handed and left-handed swastika, respectively. They are revolving doors and the direction of rotation is vital because it determines whether it will give way to a life or traffic.

Note that the clockwise swastika becomes counterclockwise when viewed from behind. Which comes to mean that both birth and death are relative and depend on the perspective from which one looks at it. A birth in life is a death in transit, and a death in life is a birth in transit. When a being dies in life, he is born in the afterlife, and vice versa. And the swastika symbol is just perfect to represent this idea of relativity between life and death.

Arguably the earliest documented archaeological evidence for the swastika, it is found widely used in the symbolic ritualistic context on multiple clay artifacts from multiple Neolithic to Old European sites: including Vinca-Turdas-Tartary, and Cucuteni-Trypillia.

Buddhism

In Buddhism, the swastika is used horizontally (unlike the Nazi swastika, which is rotated 45 degrees on the Reich flag). At least since the Liao Dynasty, it has been part of Chinese writing (in pinyin: wan4), symbolizing the character 萬 (wan4), which means 'everything' and 'eternity', and which is rarely used. Swastikas (rotating to the right or to the left) appear on the chest of some Buddha statues. Due to the association of the right-handed swastika with Nazism, Buddhist swastikas have been nearly all left-handed since the mid-XX century. This type of swastika can often be found on Chinese food packaging to indicate that such products are vegetarian and can be eaten by strict Buddhists. This same mark is found on the collars of clothing worn by Chinese children to protect them from evil spirits. The swastika also symbolizes the 4 elements that are: fire, earth, water and air.

Christianity

Some Romanesque and Gothic Christian churches contain some swastika decoration, reminiscent of earlier Roman motifs, as Christians used it to disguise a cross to avoid persecution.

According to researchers such as John Cooper, they point out that in medieval times the figure of gammadion could be found in various temples in Europe, a cross formed by four letters gamma (Γ) imitating the shape of the swastika, representing the four editors of the canonical gospels, main books of Christianity, being the center, the symbol of Jesus of Nazareth.

Other authors, such as Guillermo Alfredo Terrera, point out that there is evidence that certain Christian groups used right-handed swastikas, which they placed on their tombs and monuments, at least during the first centuries of Christian expansion in the European continent, and could be found in places as diverse as the Basilica of Santa Eulalia (Mérida) or the Notre Dame Cathedral (in Paris).

Hinduism

The swastika is found everywhere in the temples of the Hindu religion, as well as in symbols, altars, car rears, scenes and iconography in India and Nepal, both past and present. In Hinduism, the two symbols represent the two forms of Brahman (the impersonal concept of God). Clockwise represents the evolution of the universe (pravritti), represented by the creator god Brahmá,[citation needed] while counterclockwise represents the involution of the universe (nivritti), represented by the destroyer god Shivá.[citation needed] You can also see how way points towards the four cardinal points, thus symbolizing stability. Its use as a solar symbol can be seen in the representation of Suria, god of the Sun for the Hindus. It has been used as a sign of good luck. It is also conceived as a symbol of power and versions that resemble the swastika to the figure of a man are popular. Until today it is used in iantras and in Hindu religious motifs. It can be seen on temple walls throughout the Indian subcontinent. It can also be found in the notes accompanying personal gifts and in the headers of letters. The swastika is considered a sacred and auspicious symbol among the Hindus. It is normally used in the decoration of all kinds of elements related to Hindu culture. The god Ganesha is associated with the swastika symbol. Its use is widespread in India and Nepal.

Jainism

In Jainism the swastika motif is combined with that of a hand.

Other parts of Asia

In Japan, the swastika is an ancient religious symbol called manji. As such, it appears with some frequency in Japanese products exported to the West, such as comics and products derived from them.

Because of their resemblance to the Nazi swastika, the maps had to be altered in their translations for Western countries. On street maps of Japanese cities, a right-handed swastika icon indicates a Buddhist temple. In 2021, an Osaka bar closed because it used the swastika as its logo and its staff wore Nazi military uniforms.

Ancient Indo-European Traditions

In ancient Proto-Indo-European religion, the swastika or sun wheel often represented the sun and its power. It has been related to the solar cross (a symbol similar to the Celtic cross but with arms of equal length) and there were also combinations of both. In pre-Roman Hispania he appears among the Arevaci. In Germanic mythology, the swastika also represents power and illumination, which is why it was associated with thunder gods such as Thor (the swastika was the symbol of Mjolnir, Thor's hammer), in Norse mythology, and Taranis, in Norse mythology. celtic mythology. In Ireland, such a sun wheel is known as a Brigit's cross and is used to ward off evil.

In Europe at the beginning of the 20th century

British author Rudyard Kipling, heavily influenced by Indian culture, had a swastika on the cover of all of his books until the rise of Nazism made it inconvenient.

The swastika was also the symbol initially chosen in the United Kingdom by the National Savings Movement or National Savings Movement created in 1916 to finance state spending, especially war.

The boy scouts also used it as a symbol. According to Johnny Walker, Scouts began wearing it on the first Thanks Badge dating from 1911. The Badge of Merit motif, designed by Robert Baden-Powell in 1922, as a sign of good luck when to receive it, add a swastika to the Scouts' fleur-de-lis. Like Kipling, Baden-Powell was probably familiar with this symbol in India. In 1934 many scouts requested that the badge be changed because the Nazi party already used the swastika. A new merit medal without the swastika was released in 1935.

Between 1918 and 1945 the Finnish Air Force used the swastika (hakaristi, in Finnish) as its official national insignia. The Lotta Svärd organization also used it. A blue swastika was a good luck mark used by the Swedish Count Erich von Rosen who during the Finnish civil war donated the first airplane to the Finnish White Army. There is no connection to the Nazi use of the swastika. It still appears on many Finnish medals, visually disguised. In 2020 the Air Force stopped using the swastika.

The Swedish company ASEA, today part of Asea Brown Boveri, from the XIX century until 1933 had in its logo a swastika that was eventually removed.

In Latvia a swastika known as Thunder Cross or Fire Cross was the insignia of the Latvian Air Force. It was also used by the Latvian fascist Perkonkrusts (Thunder Cross) movement, as well as by non-political organizations.

Swastika is the name of a small community in northern Ontario, Canada. It is located about 580 km from Toronto and 5 km from Kirkland Lake. The town was founded in 1906 and, as a result of the discovery of gold deposits, the Swastika Mining Company was formed in 1908. During World War II the Ontario government wanted to change the name of the town but the population opposed it.

In Windsor, Nova Scotia, between 1905 and 1916, there was an ice hockey team called The Swastikas, and their uniforms featured that symbol. Teams with the same name also existed in Edmonton, Alberta, around 1916, and in Fernie, British Columbia, around 1922.

On the other hand, in Russia the swastika was also used. Good luck was attributed to him. In 1917, after the abdication of Tsar Nicholas II, the Russian provisional government designed ruble notes bearing the swastika. It should be noted that this symbol came to be used by tsarist soldiers in World War I and by some Soviets in the Russian Civil War.

In America

In Argentina

The Retiro railway station in the city of Buenos Aires was, at the time of its construction, one of the largest stations in the world, for this reason special care was taken in its construction in the first decade of the century XX. The columns of its façade are decorated with intertwined swastikas at the tips.

In the United States

For many of the Native American tribes, especially for the Hopi of Arizona, the swastika symbolizes migration, carried out at the time of the arrival of men to the fourth world through the sipapu or the ' vagina of the earth'. The god Massaw (the creator) told the newcomers to migrate in the four directions or corners of the earth to learn about life. It is also said that it was the four races that migrated: the whites to the north, keepers of fire; the reds to the east, custodians of the land; the blacks to the west, custodians of water and the yellows to the south, custodians of the air. Migration or diaspora is symbolized by the right-handed swastika (turns clockwise). On the contrary, the reunification of the races is symbolized by the left-hand rotation (against).

In line with this, for a brief time, and in tribute to these indigenous tribes of the American Southwest, the 45th Infantry Division adopted a swastika on its banner. With the rise of Nazism, in 1934, it was no longer used.

Similarly, shortly after the outbreak of World War II, several of these Native American nations, such as the Navajo, Apache, Tohono O'odham, and Hopi, issued a joint decree proclaiming that they would no longer use swastikas in their craft. The reason was due to the use of the swastika with an evil meaning during the contest. The decree was signed by representatives of these tribes. Here is the text of the decree:

Since the aforementioned ornament, which has been a symbol of friendship among our predecessors for centuries, has recently been desecrated by another nation.

Therefore we establish that from here on and forever our tribes renounce the use of the emblem commonly known as swastika or fylfot in our blankets, baskets, art objects, dress and sand paintings.

As in the United Kingdom, the swastika was a symbol of the American Scouts, and gave its name to the magazine of the women's section of the scouting movement. But in addition, this symbol of good luck was worn on North American airplanes from World War I, and was an advertising image for brands such as Coca Cola or Carlsberg, or the Californian orange brand Swastika.

In Panama

The swastika is part of the traditional ornamental motifs of some indigenous nationalities of present-day Panama, such as the Guna Yala. For example, in the San Blas archipelago, territory of the Guna nationality, you can see an orange flag with a swastika cross in the center of black in an anticlockwise direction, appearing on the shield of the extinct flag of the Republic of Tule.

In Peru

The Mochica or Moche culture (between the 2nd century BC and the 7th century AD), which developed in much of northern Peru, is known as the «victor of the desert».[citation needed] These ancient settlers were skillful builders of pyramids and hydraulic conduits, as well as connoisseurs of metallurgy and great potters. In the Huaca Rajada de Sipán site museum, located in the district of Zaña, in the coastal department of Lambayeque, 900 kilometers north of Lima, a series of ceramics are exhibited, among which a vessel with the figure of a swastika stands out. or swastika (a cross with folded arms).

It was found by archaeologists near the base of the larger pyramid. The swastika is drawn with charcoal paint on the pottery. For the Andean culture it represented a "geometric element of the permanent movement of the cycles of life", according to Walter Alva, discoverer of the Lord of Sipán (an ancient Peruvian monarch). "The swastika that identified Adolf Hitler's Nazism in Germany was misused in Europe, but for Andean culture it is a symbol of the god of wind and water. It has no political connotation," added Alva. For Luis Chero ―director of the Huaca Rajada museum―, the swastika was related to the flight of birds. "It's a cultural parallel, but that doesn't mean there was any contact with cultures in other parts of the world."

In Mexico

The cultures that inhabited Mexican and Central American soil, such as the Mayans, Aztecs and Toltecs, also used this cross and venerated it as a sacred symbol. They used the swastika in rituals of the Sun as an eternal element, in Mexico it can be seen in its different cathedrals, such as San Luis Potosí, Tampico, in the Casa Antigua Parras Coahuila, among other cultural destinations.

In Nazi Germany

For many Westerners, the swastika is primarily associated with Nazism in particular.

The Nazis adopted the swastika in 1920 but it was already in full use as a symbol among the German nationalist völkisch movements, which possessed certain mystical-esoteric whims. For this reason, they saw it appropriate to adopt it as a symbol of the "Aryan race". The use of the swastika as a symbol of the "Aryan race" goes back again to the writings of Émile-Louis_Burnouf. Following many other writers, the German nationalist poet Guido von List considered it to be a uniquely Aryan symbol. Adolf Hitler referred to the swastika as the symbol of the "Aryan man's struggle for victory" (in the book Mein Kampf).

Some authors argue that what inspired Hitler to use the swastika as a symbol of the NSDAP was its use by the Thule Society (Gr. Thule-Gesellschaft) as there were connections between them and the Party German Worker (DAP). From 1919 until the summer of 1921 Hitler used the special library of Dr. Friedich Krohn, an active member of the Thule Society. Dr. Krohn was also the dentist of Sternberg, who was named in Mein Kampf by Hitler as the designer of a flag very similar to one Hitler designed in the 1920s.[quote required] During the summer of 1920, the first home-made party flag was displayed at Lake Tegernsee.

Wolfgang G. Jilek says:

The first time the swastika was used with an ario meaning, it was on December 25, 1907, when the self-denominated New Templar Order, a secret society founded by Adolf Joseph Lanz von Liebenfels, set a yellow flag with a swastika and four lis flowers in the castle of Werfenstein (Austria).

Nazi theorists associated the use of the swastika with their theses that affirmed the cultural ancestry of the German people from the so-called Aryan race. The Nazis believed that the early Aryans of India, from whose Vedic traditions the swastika stems, were the prototype of white invaders, thus co-opting the symbol as an emblem of white supremacy.

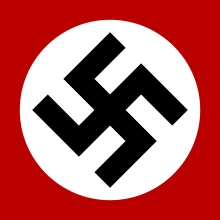

The Nazis used the black swastika (or Hakenkreuz) within a white circle on a red background, black, white and red being the colors of the former flag of the German Empire. The Nazis also used the swastika devoid of such circles and background. Adolf Hitler also wrote in his book that the final design was suggested to him by a large number of Nazi co-religionists.[citation needed ]

Two versions of the Nazi swastika are frequently found. One of them is left-handed. The other is its right-handed mirror image. Although the Nazis do not seem to have attached symbolic distinctions to both varieties, the latter is in more common use. In both, the cross appears rotated 45°.

Today, the symbolism of the swastika has been embraced by neo-Nazis. Consequently, the use of the swastika outside of a historical context is considered taboo in most of the world. Currently, German law prohibits and penalizes the public wearing of the swastika and other Nazi symbols.

For hundreds of millions of people, the swastika is associated with concepts and practices that have nothing to do with Nazism and is therefore in common use mainly in non-Western countries.

Two types of swastikas

A swastika is basically a cross that is in rotating motion. The importance of this cross is that it is in motion and, therefore, the direction of rotation is vital to correctly interpret the meaning of the symbol.

According to some, the fact that an arm points to the right does not mean that it turns to the right, quite the opposite.

The two most common descriptions are:

- swastika dextrogira (‘turning to the right’ in time sense).

- swastika levogira (‘which turns left’ in the anti-horn sense).

These terms can be used inconsistently (sometimes even by the same author), which can confuse an important point, as swastika rotation can have symbolic relevance, though ―due to the inconsistency between the information provided by different authors―little is known about this symbolic relevance.

In 1894, the Belgian lawyer and professor Eugène Goblet d'Alviella maintained (although without providing evidence) that the left-handed swastika is called sauvástika, which from the point of view of the Sanskrit language is an eyesore. A Western myth holds that only the swastika with arms bent to the right is a mark of good luck, while the swastika with arms bent to the left represents a dire omen. There is no evidence of this distinction in the history of Hinduism (from which the symbol comes). The Hindus of India and Nepal continue to use the symbol in its two variants, although the most common version is right-handed. Buddhists almost always use the levorotatory form. At the beginning of the XX century, Nazism adopted the swastika as its emblem and, following World War II, in the West it became It is mostly identified as a symbol exclusively of the Third Reich, its use prior to Nazism being practically unknown.

Origin of the swastika

Anthropological Hypotheses

The frequency with which the swastika is used is explained by the fact that it is a simple and attractive symbol that can appear without difficulty in any civilization that has developed basketry (although it may have other technical origins), and hence expand easily, due to contacts between some peoples and others. The swastika would be a very repeated design, created by the edges of the reeds or rushes used to make a basket with a quadrangular base. Other theories try to show that there was a transmission of the symbol from one culture to another. There are also those who have used Carl Jung's theories, more specifically the collective unconscious, to explain the presence of the swastika in such distant places.

While the existence of the swastika in America can be explained by the basketry theory, this fact greatly weakens the cultural diffusion theory. Although some have tried to explain this by assuming that it was transmitted by some early Eurasian marine civilization, the separate but parallel development of the symbol is the explanation most widely accepted by anthropologists.

The birth of the swastika has often been seen as related to that of other cross-shaped symbols, as well as the "solar cross" of early Bronze Age religions.

Astronomical hypothesis

Apart from the classical anthropological hypotheses, there is also an astronomical hypothesis of the origin of the swastika. This was formulated by the American astronomer Carl Sagan. According to Sagan, it is inexplicable that this symbol has been used throughout history by many civilizations distant from each other and that they would not have had any link, unless one considers the possibility that it is a symbol resulting from a common experience that all these peoples had. For Sagan, this experience could only come from heaven: it could be the vision of some peculiar star or the vision of some atmospheric anomaly.

Sagan was of the opinion that the probable origin of the swastika was the approach of a rotating comet in such a way that its axis was oriented towards the terrestrial observer. Several scientists[citation needed] have pointed to Comet Encke as the most likely candidate for this.

However, critics of this hypothesis point out that it is highly unlikely that such an event occurred,[citation needed] and believe that the use of the swastika from a merely terrestrial point of view.

Contenido relacionado

Mississippi Burning

Philippine-American War

Bejar