Sumerian

Sumerian (from Akkadian Šumeru; Sumerian cuneiform 𒆠𒂗𒂠 ki-en-gi, roughly KI & #39;land, country', EN 'lord', GI reedbed') is a historic region of the Middle East, part south of ancient Mesopotamia, between the alluvial plains of the Euphrates and Tigris rivers. The Sumerian civilization is considered the first civilization in the world. Although the origin of its inhabitants, the Sumerians, is uncertain, there are numerous hypotheses about its origins, the most currently accepted being the one that argues that no cultural rupture occurred with the Uruk period, which would rule out external factors, such as invasions or migrations from other distant territories.

The term "Sumerian" it also applies to all speakers of the Sumerian language. In that language, this region was called Kengi (ki), equivalent to the Akkadian mat Sumeri, that is, "land of Sumer".

Origin of name

The term "Sumerian" is the common name given to the ancient inhabitants of lower Mesopotamia by their successors, the Akkadian Semites. The Sumerians called themselves sag-giga, which literally means "the people of the black heads". The Akkadian word shumer may represent this name in the dialect, but it is unknown why the Akkadians called the southern lands Shumeru. Some words such as the Biblical Shinar, the Egyptian Sngr, or Indo-European Hittite Šanhar(a) may have been variants of Šumer. According to the Babylonian historian Berossus, the Sumerians were "foreigners of black heads".

History

First settlers

In Lower Mesopotamia: assuming that human settlements existed since the Neolithic as demonstrated by the Jarmo culture (6700 BC-6500 BC), and in the Chalcolithic the Hassuna-Samarra culture (5500 BC-5000 BC), El Obeid (5000 BC-4000 BC), Uruk (4000 BC-3200 BC) and Yemdet Nasr (3200 BC-3000 BC).

There are no written records from that stage to know the origin of this town, nor do the skulls found in the burials clarify the problem of their origin, because both dolichocephaly and brachycephaly are represented, with some testimonies of the type armenoid. The Sumerian sculptures that show a high rate of brachycephalic skulls in their representations are investigated, which perhaps could elucidate the origin of this people, together with the colors and dimensions of the sculptures, which are a mix between Caucasians and members of the black race. With all this, it is not enough evidence to solve the problem since the plastic could have idealized them, as it happened in the Egyptian sculptures.

The possibility of identification based on the evolution of cranial types in the Middle East as a whole has been ruled out, as these appear quite mixed. However, four large groups can be distinguished with features belonging to different periods: before 4000 B.C. C. only dolichocephalic populations of the "Mediterranean" type; the "eurafricans", which are only a variety of this group, and which did not play an appreciable role until 3000 BC. c.; the "alpine" type, brachycephalic that manifests itself moderately after 2500 BC. C., and the "Armenoids", perhaps derived from these Alpines that appear in abundance after 500 B.C. C. Cimmerian-descended peoples tend to have on average the most "rounded" (brachycephalic) than the other peoples of that area and the word "Sumerian" may be a transliteration of the word "Cimmerians" according to some philologists. This is why several researchers believe that both peoples are the same people at different times, but there is not enough evidence to support this hypothesis.

It seems possible that the Sumerians were a tribe from outside, possibly from the steppes, but their exact origin is unknown. This is what has been called since the 20th century as the "Sumerian problem."

In any case, it is during the Obeid period when advances take place that crystallize in the Uruk period, and which serve to consider this moment as the beginning of the Sumerian civilization.

Some scholars also postulate that the Sumerians established in Mesopotamia, would not have an autochthonous origin, but would come from the culture that founded the city of Mohenjo-Daro (which existed between 2600 BC and 1800 BC.) in India. Haplogroup M (mtDNA) Mitochondrial DNA was analyzed from the teeth of 4 individuals buried in ancient Terqa and Kar-Assurnasirpal, in the Euphrates Valley, from the period between 2,500 B.C. c. 500 d. C, and the individuals studied carried haplogroups M4b1, M49, and M61, which are thought to have arisen in the area of the Indian subcontinent during the Upper Paleolithic and are absent in people living in the region today. The fact that the individuals studied comprised both men and women, each living in a different period, suggests that the nature of their presence in Mesopotamia was long-lasting rather than incidental.

Uruk Period

Uruk, the "Erec" Biblical and Arabic "Warka", is the scene of fundamental discoveries for the history of humanity: the wheel appears around 3500 B.C. C., and writing in 3300 B.C. C., which is the oldest dating of clay tablets with cuneiform writing found to date. These written records confirm that the Sumerians were not an Indo-European people, nor a Camita, nor a Semite, nor an Elamo-Dravid (group, the latter, to which the Elamite people belong, for example). This is demonstrated by its agglutinative type tongue. However, it is speculated, as has been said, that the Sumerians were not the first people to settle in lower Mesopotamia, in the lower reaches of the Fertile Crescent, but that they arrived at a certain time in the Copper Age or Chalcolithic, there around the year 3500 before our era, during the period now called Uruk.

Archaic Dynastic Period

The spread of the advances of the Uruk culture throughout the rest of Mesopotamia gave rise to the Sumerian culture. These techniques allowed the proliferation of cities for new territories. These cities were soon characterized by the appearance of walls, which seems to indicate that wars between them were frequent. It also highlights the expansion of writing that jumped from its administrative and technical role to the first dedicatory inscriptions on enshrined statues in temples.

Despite the existence of the Sumerian royal lists, the history of this period is relatively unknown, since a large part of the reigns exposed in them have impossible dates. Actually, these lists were drawn up from the 17th century B.C. C., and its creation was probably due to the desire of the monarchs to trace their lineage back to epic times. Some of the kings are probably real but there is no historical record of many others and others whose existence is known do not appear in them.

The name of the oldest sovereign known to us is Enmebaragesi, king of the city of Kish, and it is given to us by an inscription on a fragment of a stone vessel, possibly a ritual offering. His name is also included in the Sumerian Royal List.

Akkadian rule

Circa 2350 B.C. C., Sargon, a usurper of Akkadian origin, seized power in the city of Kiš. He founded a new capital, Agade, and conquered the rest of the Sumerian cities, defeating Lugalzagesi, the hitherto dominant king of Umma. This was the first great Empire in history and would be continued by Sargon's successors, who would have to face constant revolts. Among them stood out the grandson of the conqueror, Naram-Sin. This stage marked the beginning of the decline of the Sumerian culture and language in favor of the Akkadians.

The empire fell apart around 2220 B.C. C., due to the constant revolts and invasions of the Amorite nomads and, mainly, Gutis. After its fall, the entire region fell under the rule of these tribes, who imposed themselves on the city-states of the region, especially around the destroyed Agade. The Sumerian chronicles consistently describe them in a negative light, as "horde of barbarians" or "mountain dragons", but it is possible that the reality was not so negative; in some centers there was a true flowering of the arts. This is the case of the city of Lagaš, especially during the government of patesi Gudea. In addition to artistic quality, materials from distant regions were used in Lagaš's works: cedar wood from Lebanon or diorite, gold and carnelian from the Indus Valley; which seems to indicate that trade should not have been particularly weighed down. The southern cities, further away from the center of Guti power, bought their freedom in exchange for large tributes; Uruk and Ur prospered during their 4th and 2nd Dynasties.

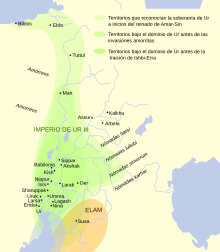

The Sumerian Renaissance

According to a commemorative tablet it was Utu-hengal, king of Uruk, who around 2100 B.C. C. defeated and expelled the Guti rulers from the Sumerian lands. His success would not be of much benefit to him since shortly after the king of Ur, Ur-Nammu, achieved hegemony in the entire region with the so-called III dynasty of Ur or Sumerian Renaissance. The empire that emerged as a result of this hegemony would be as extensive or more than that of Sargon, from which he would take the idea of a unifying empire. This influence can even be seen in the naming of the monarchs, who, in imitation of the Akkadians, will call themselves "kings of Sumer and Acad"

Ur-Nammu will be succeeded by his son, Shulgi, who fought against Elam and the nomadic tribes of the Zagros. This was succeeded by his son Amar-Suen (Amar-Sin) and this first by his brother, Shu-Sin and later by another Ibbi-Sin. In the latter's reign the attacks of the Amorites, coming from Arabia, became especially strong and in 2003 B.C. C. the last predominantly Sumerian empire would fall. From then on it will be the Akkadian culture that predominates and, later, Babylon will inherit the role of the great Sumerian empires.

Ur III Period

The demise of the Akkadian Empire allowed the rebirth of Sumer and the return to the regime of the city states. The reforms of Gudea of the Lagaš Dynasty in this Neo-Sumerian era (2175 BC) are of great relevance. Later in the III Dynasty of Ur, Ur-Nammu carried out a well-structured code with numerous changes. At this time they begin to be named as Kings of Sumer and Akkad (2111 BC). Shulgi in 2093 BC. C. will promote an evolution referring to the existing weights and measures, at the same time that it will reinforce the borders due to the harassment of the Semites-Amorites.

Despite this, it eventually succumbed to attacks by the Amorites who led Elamite-Semitic auxiliaries from the Iranian plateau, who prevailed and sacked Ur (2003 BC). It returns to a state of political fragmentation and local dynasties proliferate. Rimsin will create a small empire in 1792 BC. C. where private property will be introduced, giving a pre-capitalist society. Instead, an Amorite dynasty (1792 BC) will be enthroned in Babylon.

The society of the Third Dynasty of Ur is organized as follows:

- mashda: "seconds."

- eren: "murder of palace." Possibly it will be about servitude or court of the palace.

- go/game: servants (books). Parents sold their children to the temple even though the little ones did not lose their status of freedom for it.

- namra: slaves. They were distinguished by wearing a necklace with the name or a peel of hair on the head.

Social organization

With respect to social organization, Sumerian society was hierarchical and stratified, like all other civilizations. At the top of the social pyramid was the king, who was followed in importance by an elite of priests, military chiefs, and high-level officials. Next are the merchants, minor officials, specialized artisans, and then the peasants and artisans. The lowest level of society corresponded to the slaves.

Administration and politics

At the end of the 4th millennium B.C. C. Sumer was divided into a dozen independent city states whose limits were defined by means of canals and cairns. These cities were great mercantile centers. Each was centered on a temple dedicated to the city's particular patron god and ruled by a "patesi" (Ennsi), or sometimes by a king (lugal). The patesi were supreme priests and absolute military chiefs, aided by an aristocracy made up of bureaucrats and priests. The patesi controlled the construction of dikes, irrigation canals, temples and silos, imposing and managing the taxes to which the entire population was subject. Sumerian city-states were traditionally city-temples, as the Sumerians believed that the gods founded cities to be centers of worship. Later, according to religion, the gods limited themselves to communicating to the sovereigns the plans of the sanctuaries. The link of the pathesis with the religious rites of the city was extremely intimate.

The temples (among which the pyramidal ziqqurat stood out) were linked to state power, and their wealth was usufructed by the sovereigns, considered intermediaries between gods and men. Along with the temples of the cities, honoring their patron god, it was not uncommon for ziggurats to be erected; solid brick pyramids baked in the sun that served as sanctuaries and access to the gods when they descended to their town during the festivities.

With the development of cities, the attempts of supremacy of some over others became inevitable. For a millennium there were struggles for control over the rights to use water, trade routes and the collection of tributes from nomadic tribes.

The first five cities from which predynastic power was exercised are —the current name of the place appears in parentheses—:

- Eridu (Tell Abu Shahrain)

- Bad-tibira (probably Tell al-Madain)

- Larsa (Larsa)Tell as-Senkereh)

- Sippar (Tell Abu Habbah)

- Shuruppak (Shuruppak)Tell Fara)

Other major cities:

- Kiš (Tell Uheimir and Ingharra)

- Uruk (Warka)

- Ur (Tell al-Muqayyar)

- Nippur (Afak)

- Lagaš (Tell al-Hiba)

- Ngirsu (Tello or, Telloh)

- Umma (Tell-Yoja)

- Hamazi

- Adab (Tell-Bismaya)

- Mari (Tell Hariri)

- Akshak

- Akkad

- Isin (Ishan al-Bahriyat)

Other minor cities, from south to north:

- Kuara (Tell al-Lahm)

- Zabala (Tell Ibzeikh)

- Kisurra (Tell Abu Hatab)

- Marad (Tell Wannat es-Sadum)

- Dilbat (Tell ed-Duleim)

- Borsippa (Birs Nimrud)

- Kutha (Tell Ibrahim)

- Der (al-Badra)

- Ešnunna (Tell Asmar)

- Nagar (Tell Brak)

Language and writing

Sumerian is considered a language isolate as it is not related to any known language family, although many unsuccessful attempts have been made to relate Sumerian to other language groups. Sumerian is clearly different from Akkadian, a language of clear Semitic origin, with which it coexisted in the region, alternating as dominant languages. Both languages used the cuneiform script, originally developed by the Sumerians and whose use surpassed that of the Sumerian language itself by more than a millennium.

Sumerian was an agglutinative language, meaning monemes (units of meaning) were glued together to create whole words, in contrast to inflectional languages such as Akkadian or Indo-European languages. Therefore, typologically, Sumerian differs notably from other languages in the region, since Sumerian prefers to use affixes to express the same thing. On the other hand, other close languages such as Elamite, the Hurrito-Urartian languages and some Caucasian languages show linguistic typologies more similar to Sumerian, although they do not seem directly related to it.

The Sumerians invented pictorial hieroglyphs that later gave rise to cuneiform proper, and their language along with that of Ancient Egypt compete for credit as the earliest documented language. A large corpus consisting of hundreds of thousands of Sumerian texts has survived, the vast majority of these texts on clay tablets. Known Sumerian texts include personal texts and letters of business and transactions, receipts, lexical lists, laws, hymns and prayers, magical incantations, and even scientific texts on mathematics, astronomy, and medicine. Monumental inscriptions and texts written on different objects like statues or bricks were also quite common. Many texts survived in multiple copies, as they were transcribed several times by trainee scribes. Sumerian remained the liturgical language used in religious services and the language of legal texts in Mesopotamia long after the Semites became the hegemonic group in the region.

The understanding of Sumerian texts can be complicated today, even for experts, mainly due to the use of hieroglyphic characters that are difficult to interpret. The most difficult are the oldest texts, which in many cases do not give the entire grammatical structure of the language that was always changing.

Religion and beliefs

Dealing with a subject such as Sumerian religion can be complicated, since the practices and beliefs adopted by those peoples varied greatly through time and place, each city possessing its own mythological and/or theological vision. The Sumerians were possibly the first to write about their beliefs, which later became the inspiration for much of Mesopotamian mythology, religion, and astrology, although this does not imply that their religion was the first and that they did not borrow customs and rites from other peoples..

The Sumerians saw the movements of their year as the magic of the spirits, magic that was the only explanation they had for how things worked. Those spirits were their gods.[citation needed] And with many spirits around, they believed in various gods, who had human emotions. They believed that the sun, moon, and stars were gods, as were the reeds that grew around them and the beer they brewed.

They believed that the gods controlled the past and the future, that they revealed to them the abilities they possessed, including writing, and that the gods provided them with everything they needed to know. They had no vision that their civilization had developed by their own efforts. And they also had no vision of technological or social progress.

Each of the Sumerian gods (in their own language, dingir and in the plural, dingir-dingir or dingira-ne-ne) were associated with different cities, and the religious importance attributed to them intensified or declined depending on the political power of the associated city. According to the Sumerian tradition, the gods created the human being from mud with the purpose of being served by their new creatures. When angry or frustrated, the gods expressed their feelings through earthquakes or natural catastrophes: the primordial essence of Sumerian religion was therefore based on the belief that all humanity was at the mercy of the gods. Note the similarity of the creation of man from mud with the Genesis account.

Among the main mythological figures worshiped by the Sumerians, it is possible to cite:

- An (or Anu), god of heaven;

- Nammu, the goddess-mother;

- Inanna, the goddess of love and war (equivalent to the goddess Ištar of the Akkadians);

- Enki in the temple of Eridu, the protective god of men, controller of the fresh water of the depths below the earth;

- Utu in Sippar, the sun god;

- Nannar, the moon god in Ur;

- Enlil, the god of the wind.

The Sumerians probably dug a few meters into the earth and found water [citation needed]. The Sumerians believed that the earth was a large disk floating in the sea. They called that sea Nammu and thought that it had always been in time. They believed that the fish, birds, wild pigs, and other creatures that dwelt in the wet marshlands had sprung from Nammu.

According to them, Nammu had created heaven and earth. The sky had separated from the earth, giving birth to the male god An and the earth, a goddess named Ki. They believed that Ki and An had produced a son named Enlil, who was the personification of atmosphere, wind, and storm. They believed that he separated the day from the night and that he had opened an invisible shell, letting water fall from the sky. They believed that together with his mother and Ki, Enlil laid the foundations for the creation of plants, humans, and other creatures, that he germinated the seeds, and that he had shaped humanity out of clay, impregnating it.

The universe consisted of a flat disk enclosed by a brass dome. Life after death implied a descent into the vile underworld, where eternity was spent in a pitiful existence, in a kind of hell.

They believed that crops grew because a male god was mating with his goddess wife. They viewed the hot, humid summer months, when the fields and meadows were dyed brown, as the time of the death of the gods. When the fields bloomed again in spring, they believed their gods were resurrected. They marked this as the beginning of the year, which was celebrated in their temples with music and songs.

They did not believe in social change, although Sumerian priests altered the stories they told, creating new twists on ancient tales; not acknowledging this as a human-induced change or wondering why they had failed to get it right the first time. The new ideas were simply revelations from their gods.

There were different kinds of priests. Some of the most common were:

- āšipu, exorcist and doctor.

- bārûastrologer and adivine.

- qadištuPriestess.

Sumerian temples consisted of a central nave with corridors on both sides, flanked by chambers for the priests. At one end of the corridor was a pulpit and a platform built with mud bricks, used for animal sacrifices and plant offerings.

Granaries and storehouses were generally located in the vicinity of temples. Later, the Sumerians began to build their temples on top of the artificial, embanked, multifaceted hills - such special temples were called ziggurats.

The Sumerians were precursors of many religious concepts, cosmogonic sagas and stories that later appeared collected by other Mesopotamian peoples and neighboring regions [citation needed]. Among them we can cite: the creation of the world, the separation of the primordial waters, the formation of man with clay or the ideas of paradise and the Universal Flood (which appears in the Epic of Gilgameš). Writings by V. Scheil and S. N. Kramer, consider the creation of Eve from Adam's rib as a Sumerian myth, since in Sumerian, the words "make live" and "rib" they were spelled the same: ti. Also the idea of the resurrection of the dead, attributed to innumerable religions, appears in Sumer for the first time.

Agriculture and livestock

The Sumerians maintained a production of barley, chickpeas, lentils, millet, wheat, turnip, dates, onion, garlic, lettuce, leek, poppy and mustard. They also raised cows, sheep, goats, and pigs. In addition, they used oxen as the main option for cargo work and donkeys as transport animals. The Sumerians caught fish in the Tigris and Euphrates rivers and canals, and hunted birds on their banks and swampy mouths.

Sumerian agriculture depended heavily on irrigation, carried out through the use of canals, ponds, dikes, and water reservoirs. The frequent and violent flooding of the Tigris, and to a lesser extent, the Euphrates, meant that the channels required frequent repair and the continuous removal of silt, and the continuous replacement of inspection markers and cairns. The government ordered slaves, forced laborers, and certain citizens to work on the canals, although the rich could be excluded from this task.

After the flood season and after the season of the vernal equinox and the Akitu or New Year Festival, the canals were opened, the peasants irrigated their fields and drained the surplus water. Later they let the steers trample the earth and kill the weeds. The next step was to dredge the fields with pickaxes. After it was dry, they plowed, harrowed, and harrowed the field three times, turning the soil over with a hoe before planting. Unfortunately, the high evaporation rate led to a gradual increase in the salinity of the fields. By the Ur III period, farmers switched from wheat to barley as the main crop, since barley is more tolerant of salt.

The Sumerians harvested during the dry season of autumn in three-person teams consisting of two reapers and a baler. The peasants used a type of archaic harvester to separate the head of the cereals from their respective stems: a kind of sorting car, which separated the grains from the cereals. Then they sifted the mixture of grains and chaff.

Military Features

The almost constant wars, during 2000 years, between the Sumerian city states helped to develop the technique and military technology to a high level. The first recorded war was between Lagaš and Umma in 2525 BC. C. on a stele called the Stele of the Vultures. This record also shows the king of Lagaš leading a Sumerian army composed mostly of infantry. Foot soldiers carried spears, copper helmets, and leather or wicker shields. The spearmen are shown arranged in what appears to be a phalanx formation, which requires training and discipline. This implies that the Sumerians have made use of professional soldiers.

The key flaw for the Sumerian army was its poor strategic position. The natural obstacles to defense that existed were on the western (desert) and southern (Persian Gulf) borders. When populous and powerful enemies appeared from the north or east, the Sumerians were susceptible to attack. The Sumerians participated in siege wars between their cities, defended by mud brick walls that, obviously, could not stop the enemies who already knew that material.

The Sumerians invented the war chariot, to which they tied onagers (wild donkeys). Those older tanks did not perform as well in combat as the models built later. Some suggest that military chariots served primarily as a means of transportation, although in wartime they carried tomahawks and spears. The Sumerian chariot or rather wagon consisted of a box with four solid wheels driven by a team of two people and tied to four onagers. The chariot was made of woven baskets, and the wheels were a solid three-piece design. The Sumerians used sheaths and simple bows, later the compound bow would be invented.

Culture

Architecture

The Tigris-Euphrates plain was devoid of stone and trees. Sumerian buildings included planoconvex structures made of mud bricks, a very abundant material, devoid of mortar or cement. Because planoconvex bricks were relatively unstable in composition, Sumerian masons added an extra coat of bricks, laid perpendicularly every few courses. So there, they filled the holes with bitumen.

The buildings made with mud bricks ended up deteriorating, so they were periodically destroyed, leveled and rebuilt in the same place. This constant rebuilding gradually raised the level of the cities, so that over the centuries they rose above the plain around them. The resulting constructions were known as the tell and were found throughout the ancient Near and Middle East.

The most famous and impressive type of Sumerian buildings were the Ziggurats or stepped towers, a construction of long and wide superimposed platforms on top of which were temples. Some scholars have theorized that these structures could have been the base of the Biblical Tower of Babel [citation needed], which is described in Genesis.

Sumerian cylinder seals also describe houses built of reeds, similar to those built by the lowland Arabs of southern Iraq as recently as 400 BCE. C. On the other hand, the Sumerian temples and palaces made use of more advanced materials and techniques such as reinforcements (supports for the bricks), recesses (corners), pilasters and clay nails covered with baked bricks, more resistant than raw ones. dried in the sun

Math

The Sumerians developed a complex system of metrology around 4000 B.C. C. This advanced metrology resulted in the creation of arithmetic, geometry, and algebra. From 2600 B.C. C. onwards, the Sumerians wrote multiplication tables on clay tablets and dealt with geometric exercises and division problems. The first traces of Babylonian numbering also date back to this period. The period from 2700 to 2300 BC. C. saw the first appearance of the abacus, and a table of successive columns that delimited the successive order of magnitude of its sexagesimal numeral system. The Sumerians were the first to use a positional notation number system. Other Mesopotamian peoples may have used some form of slide rule in astronomical calculations.

Medicine

A tablet found in Nippur can be considered the world's first manual of medicine. On that tablet, where there were chemical and magical formulas (spells), they used such specialized terms that the help of chemists was required to translate them.

In pharmacology, plant, animal, and mineral substances were used. Laxatives and diuretics were the majority of the remedies in that town. Certain surgeries were also put into practice. The Sumerians manufactured nitrate, obtained from urine, lime, ashes or salt. They combined these materials with milk, cobra skin, tortoise shell, cassia, myrtle, thymus, willow, fig, pear, fir, and/or date. From there, they mixed these agents with wine, using the result obtained in two ways: either passing the product as if it were a cream, or later it was mixed together with the beer, consuming the remedy orally.

The Sumerians explained the disease as a consequence of the imprisonment, and the consequent attempt to escape, of a demon inside the human body. The goal of the remedy was to persuade the demon to believe that continuing to reside in that body would be an unpleasant experience. Commonly the Sumerians placed a lamb or a goat near the sick person. In the case of not having sheep available, they tried their luck with a statue, which, if they managed to transfer the demon inside it, would be covered with bitumen.

Literature

Sumerian literature comprises three major themes: myths, hymns, and lamentations. The myths are made up of brief stories that try to outline the personality of the Mesopotamian gods: Enlil, the main god and progenitor of the minor divinities; Inanna, goddess of love and war, or Enki, god of drinking water, often in conflict with Ninhursag, goddess of mountains. Hymns are texts in praise of gods, kings, cities or temples. Lamentations recount catastrophic themes such as the destruction of cities or temples and the resulting abandonment of the gods.

Some of these stories may have been supported by historical events such as wars, floods, or the building activity of an important king, magnified and distorted over time.

A creation typical of Sumerian literature was a type of dialogue poems based on the opposition of contrary concepts. Proverbs are also an important part of Sumerian texts.

Legacy

The Sumerians are perhaps best remembered for their many inventions. Some specialists credit them with the invention of the wheel and the potter's wheel. Their cuneiform writing system was the first writing system for which there is evidence, anticipating Egyptian hieroglyphics by at least 75 years.[citation needed] The Sumerians were among the earliest astronomers, possessing the first known heliocentric vision (the next would appear back in 1500 BC by part of the Vedas in India). They also claimed that the solar system was made up of five planets (since only five planets could be seen with the naked eye).

They also developed mathematical concepts using number systems based on 6 and 10. Through that system, they invented the clock with 60 seconds, 60 minutes, and 12 hours, in addition to the 12-month calendar we use today. They also built legal and administrative systems with judicial courts, prisons, and the first city states. The invention of writing made it possible for the Sumerians to store knowledge and transfer it to others and to subsequent generations. This led to the creation of schools, education and the officialization of mathematics, religion, bureaucracy, division of labor and social class systems.

The Sumerians also invented the chariot and possibly military formations. They invented beer. Most important of all, perhaps, is the fact that according to many scholars, the Sumerians were the first to treat both plants and animals. In the case of the former, through systemic planting and harvesting of a mutant grass offspring, currently known as einkorn, and millet and wheat seeds. Regarding the second, the Sumerians domesticated through the confinement and procreation of ancestral rams (similar to the ibex) and wild cattle (buffaloes). It was the first time that these species were domesticated and bred on a large scale.

Contenido relacionado

Louis XVI of France

El Cid (film)

Fanariots