Struthiomimus altus

Struthiomimus altus is the only known species of the extinct genus Struthiomimus (lat., " ostrich mimic") of ornithomimid theropod dinosaur that lived at the end of the Cretaceous period, 76 and 70 million years ago, during the Campanian, in what is now North America. Its remains have been found in Alberta, Canada and Wyoming, United States. Its generic name is derived from the Latin, passing through the Greek στρουθιον, strouthion, which means “ostrich”, and μιμος, mimos , which means "mime" or "imitator", in the sense of "similar to an ostrich", in Spanish estrutiomimo. The specific term altus, from Struthiomimus altus, comes from the Latin meaning “high” or “noble”.

Description

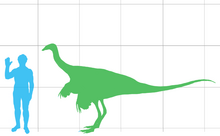

Struthiomimus was over 3 meters tall, yet it did not weigh much due to its hollow bones and overall lightness of its skeleton. Its legs indicate that it could have been an excellent runner, with great affinity with the current ostrich. Struthiomimus is one of the most common dinosaurs in Dinosaur Provincial Park. Its abundance suggests that it was herbivorous or omnivorous rather than carnivorous.

An adult Struthiomimus reached about 4.3 meters long and 1.4 meters high at the hip, weighing about 150 kilograms, a size and mass typical of ornithomimids that differed from closely related genera such as Ornithomimus and Gallimimus in proportions and anatomical detail.

Overall the body exhibited a fragile and slender build, featuring a proportionately small head on long necks, which made up about 40% of the body length in front of the hips. The skull was made up of orbits, sockets eyes relatively large. It had a toothless snout with a straight beak at the tip of the premaxilla. The lower jaw had 2 minute pairs of mandibular fenestrae in its lower part. With its neck raised upwards, it would have reached 2 meters in height. Both the front and hind limbs were long, as was its already mentioned neck, and its tail, which ended in a rigid point. The legs were designed primarily for speed, and would have served it well against predators.

Their vertebral column consisted of 10 neck vertebrae, 13 back vertebrae, 6 hip vertebrae, and about 35 tail vertebrae. Their tails were relatively stiff and were probably used for balance. They had arms and legs. hands long and slender, with immobile forearm bones and limited opposability between the first and second fingers. As in other ornithomimids, but unusually among theropods, all three fingers were roughly equal in length, and the claws were slightly curved. Henry Fairfield Osborn describing a skeleton of S. altus in 1917, compared the arm to that of a sloth. These may have been adaptations to support the wing feathers. It is likely that it had feathers all over its body. Struthiomimus differed from its close relatives only in subtle aspects of anatomy. The edge of the upper bill was concave in Struthiomimus, unlike Ornithomimus, which had straight bill edges. Struthiomimus had longer hands on relation to the humerus than other ornithomimids, with particularly long claws. Its forelimbs were more robust than those of Ornithomimus.

Their eating habits are still unknown and various hypotheses are circulating about them. Most likely, according to several studies, it was omnivorous or herbivorous. In addition, gastroliths (stones that helped digest food in the stomach when it was not crushed) have been found in a specimen, something common in herbivorous dinosaurs, although this would not determine their diet with certainty as such stones have also been found in carnivorous dinosaurs. It had prehensile hands with 3 curved claws, which it is theorized may have helped to grasp fruits or branches with leaves; however, they could also be used to tear their prey apart.

It may have been covered in feathers, as can be speculated from its phylogenetic position, but this is not proven with certainty, as no fossilized impressions of any integument of the strutiomime have been discovered to support this. Remains of several individuals have also been found together, leading to the belief that these dinosaurs lived in herds.

History

In 1901, Lawrence Lambe found some incomplete remains, the holotype CMN 930, which he named the following year as Ornithomimus altus, placing them within the same genus as the described remains by Othniel Marsh in 1890. However, in 1914, a nearly complete skeleton, cataloged AMNH 5339, was discovered by Barnum Brown in the Red Deer River beds, and was officially described as a separate genus by Henry Fairfield Osborn in 1916, although he also considered it a subgenus of Ornithomimus in his study. Dale Russell made Struthiomimus a full genus in 1972, at the same time as reported several other specimens, including AMNH 5375, AMNH 5385, AMNH 5421, CMN 8897, CMN 8902 and ROM 1790, all partial skeletons. The type species, S. altus, is known from various skeletons and skulls, In 1916 Osborn also changed the name from Ornithomimus tenuis Marsh 1890 to Struthiomimus tenuis. today it is considered a nomen dubium. In 2016, ROM 1790 became the holotype of a new genus and species, Rativates evadens.

In subsequent years, William Arthur Parks named four more species of Struthiomimus. In 1926 he named the first of them Struthiomimus brevitertius, which became Dromiceiomimus brevitertius. Later, in 1928, he named Struthiomimus samueli, which was renamed Dromiceiomimus samueli. In 1933, he named Struthiomimus curellii, which was recombined as Ornithomimus curellii by Russell and Chamney in 1967, then misspelled as Ornithomimus currelli by Eberth in 1997 and subjectively synonymized with Ornithomimus edmontonicus by Steel in 1970. In that same work, he named to Struthiomimus ingens, was recombined as Ornithomimus ingens by Russell and Chamney in 1967, then subjectively synonymized with Dromiceiomimus brevetertius by Osmólska et al. in 1972 and was finally subjectively synonymized with Ornithomimus edmontonicus by Makovicky et al. in 2004. In 1997 Donald Glut mentioned the name Struthiomimus lonzeensis. This was probably a slip of calami, an inadvertent typing mistake, an error by Ornithomimus lonzeensis.

Struthiomimus altus comes from the Oldman Formation of the Upper Campanian, Judithian era. Remains of Struthiomimus also come from the Dinosaur Park Formation, dating to the late Campanian. There are remains of Struthiomimus from the Horseshoe Canyon Formation, which dates to the late Campanian and early Maastrichtian, forming the Edmontonian era. Because dinosaur faunas show rapid productivity, it is likely that these Struthiomimus specimens from younger times belong to a new species, but there is very little known material to say whether or not these specimens belong to a new species. S. altus, although they have not been given a new name. Of the specimens found in Alberta, some were found in and under ash piles, suggesting that a forest fire may have killed them.

Additional specimens of Struthiomimus from the lower Lance Formation and equivalents are larger, similar to Gallimimus in size, and tend to have straighter, more elongated claws, similar to those seen in Ornithomimus. A relatively complete specimen from the Lance Formation, BHI 1266, was originally referred to as Ornithomimus sedens, named by Marsh in 1892 and later classified as Struthiomimus sedens. A 2015 paper by van der Reest et al. listed BHI 1266 as Ornithomimus sp., while another paper in the same year considered the specimen Struthiomimus sp. pending a reassessment of both genera.

Classification

Struthiomimus is a member of the family Ornithomimidae, a group that also includes Anserimimus, Archaeornithomimus, Dromiceiomimus, Gallimimus, Ornithomimus and Sinornithomimus.

Just as the fossil remains of Struthiomimus were erroneously assigned to Ornithomimus, the family to which the genus belongs, Ornithomimidae, also underwent changes over the years. For example, O.C. Marsh initially included Struthiomimus in the Ornithopoda, a large clade of dinosaurs not closely related to theropods. Five years later, Marsh classified Struthiomimus in the Ceratosauria, In 1891, Baur placed the genus within Iguanodontia, Closer to the present, D A. Russell and Z. Dong in 1993, referred Struthiomimus to Oviraptorosauria. But later there were numerous studies that accepted them to Struthiomimus within the Coelurosauria, thus modifying the taxa of the group. Recognizing the difference of ornithomimids compared to other theropods, Rinchen Barsbold placed the ornithomimids within their own infraorder, Ornithomimosauria, in 1976.

The breadth of Ornithomimidae and Ornithomimosauria varied with different authors. Paul Sereno, for example, used Ornithomimidae to include all Ornithomimosauria in 1998, and subsequently switched to a more exclusive definition that nested Ornithomimidae, the advanced ornithomimosaurs, within the larger, more general group of Ornithomimosauria, a classification scheme that was adopted by many other authors in the early 2000s. Struthiomimus forms the family together with Anserimimus, Archaeornithomimus, Dromiceiomimus, Gallimimus, Ornithomimus and Sinornithomimus, bearing a little more similarity to Dromiceiomimus and Ornithomimus, with which it has been confused several times already. Anatomically, the Ornithomimosauria represent the group of non-avian dinosaurs most closely related to ostriches.

Phylogeny

The following cladogram is based on Turner, Clarke, Ericson, & Norell, 2007. Clade naming follows the definition in Sereno, 2005.

| Ornithomimosauria |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

However, Xu et al., 2011 proposes:

| Ornithomimidae |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Paleobiology

In a 2001 study by Bruce Rothschild and other paleontologists, fifty foot bones referred to Struthiomimus were examined for signs of stress fracture, but found none.

Posture

Struthiomimus was one of the first theropods imagined from the beginning with a horizontal posture. Osborn in 1916 left the animal intentionally depicted with a raised tail. This newer view created an image that is much more reminiscent of modern flightless birds, such as the ostrich to which this dinosaur's name refers, but only very much. it would later be accepted for all theropods.

Struthiomimus normally walked and ran with the tail horizontal, without dragging it. But there are some groups of advanced theropods that are capable of maintaining a posture with the body at 45 degrees or less from the vertical direction and the tail trailing along the ground, a pose known as 'tripod-standing'. Therefore, Struthiomimus, being an ornithomimid, is a dinosaur that could maintain its posture that way thanks to its hip joints, but perhaps only for a short time.

The old posture with which Struthiomimus was represented was incorrect since it was always tripod in locomotion, since it was most likely only maintained for surveillance tasks, performing sexual displays or simply observing its companions. surroundings. The maximum that Struthiomimus could rise is shown in the right image, because if his posture turned more degrees he would have dislocated or weakened several joints.

Food

There is much discussion about the feeding habits of Struthiomimus. Due to its straight-edged bill, it is thought that Struthiomimus was probably omnivorous or herbivorous. Some theories suggest that it could have been an inhabitant of shores where it ate insects, crabs, shrimp, and possibly the eggs of other dinosaurs. Some paleontologists point out that it is more likely a carnivore, since it is classified within the theropod group. This theory had not been rejected until Osborn, who described and named the dinosaur, proposed that it probably fed on buds and shoots of trees, shrubs, and other plants, using its forelimbs to grasp branches and its long neck to select particular objects. The hypothesis that Struthiomimus was herbivorous is also supported by the unusual structure of its hands. The second and third fingers were the same length, could not function independently, and were probably attached by skin. This indicates that the hand was used as a 'hook', to bring branches or fern fronds within reach. The shoulder girdle structure did not allow for high arm lift or was optimized for low reach. The hand could not fully flex for a grasping motion or extend for raking. This indicates that the hand was used as a "hook" or "clamp", to bring branches or fern fronds to shoulder height within reach. However, these adaptations could have been used for the support of wing feathers.

Speed

The hindlimbs of Struthiomimus were long, much like those of an ostrich, especially since the tibia was much larger than the femur, a remarkable feature in the skeleton of birds. The joint muscles ensured that the legs could move quickly, and its three metatarsals were combined with each other to transfer the force of the footfall from the paws to the legs and to the rest of the body. The supposed speed of the strutiomime was, in fact, its only defense against predators, such as dromaeosaurids, such as Saurornitholestes and Dromaeosaurus and tyrannosaurids, such as Daspletosaurus and Gorgosaurus, which lived at the same time. It has been estimated that they could have been able to run between 50 and 80 km/h, and that when they took 2 strides per second, their maximum length could have been 6 meters.

Struthiomimus was one of the first coelurosaurs to organize its limbs, muscles, and tails like birds, with a caudofemoralis muscle in the leg and a tail that acted more like a rudder to change direction at high speed. speed. But since Struthiomimus had a smaller and lighter tail, it would carry more weight on top if it didn't have its legs below its center of balance. Holding the femur more horizontally brought its legs forward and balanced the animal.

The estimated speed of Struthiomimus shows that it could have been a runner. However, it most likely could not achieve this ability at the rate that modern ostriches do, because its long front legs and short tail made it heavier, and therefore its speed would have been limited in running.

Paleoecology

The fossil remains of S. altus are only known definitively from the Oldman Formation, dating to 78–77 million years ago during the Campanian stage of the late Cretaceous period. A younger species, yet to be named, which apparently differed from S. altus for having longer, slender hands, is known from several specimens found in the Horseshoe Canyon Formation and lower Lance Formation, between 69 and 67.5 million years ago, early Maastrichtian. Struthiomimus lived in what is now North America, in climates and environments very different from today's. The landscape represented by the deposits of the Dinosaur Provincial Park were low-lying subtropical coasts surrounded by large rivers in which both terrestrial and marine life must have proliferated. The strutiomime could have been easily adapted to this environment thanks to the balanced climate and the abundance of food.

Struthiomimus must have been, due to its speed, difficult prey for many carnivores such as Daspletosaurus and Gorgosaurus. For other smaller carnivores, such as dromaeosaurids such as Saurornitolestes and Dromaeosaurus, hunting would have been easier thanks to their great speed, comparable to that of Struthiomimus. While herds of ceratopsians, such as Chasmosaurus and Styracosaurus, and hadrosaurids, such as Parasaurolophus and Lambeosaurus, had migrated across the open grasslands.. The environment where Struthiomimus lived also contained other archosaurs such as pterosaurs, plesiosaurs, and mosasaurs on its beaches, seas, and rivers. There were also numerous kinds of fish, amphibians, reptiles, insects, and crustaceans.

Struthiomimus in popular culture

- Represented by the technique go motion by the technician in special effects Phil Tippett, Struthiomimus It appears stealing and devouring eggs Hadrosaurus in the 1985 documentary Dinosaurs.

- Struthiomimus appears in the second part of The Land Before TimeThe cartoon movie The Land Before Time II: The Great Valley Adventure (of Roy Allen Smith, 1994, entitled in Spanish The Land Before Time 2: The Adventure of the Great Valley in Spain In search of the enchanted valley 2: Adventures in the great valley). There is a couple of them as the main villains of this film, in which they try to steal an egg of tyranosaurus found by the protagonists, whom they also attack.

- Struthiomimus also makes appearance in the film Dinosaur (produced in 2000 by Walt Disney Pictures) as a desert solo hunter.

- The music group Fourth Grade Security Risk has created a song entitled The Struthiomimus Strut.

Contenido relacionado

Endocardium

Adrenocorticotropic hormone

Allolepis texana