Stephen jay gould

Stephen Jay Gould (September 10, 1941 – May 20, 2002) was an American paleontologist, geologist, evolutionary biologist, historian of science, and one of the world's most influential and widely read popularizers of science. of his generation.

Gould spent most of his career teaching at Harvard University and working at the American Museum of Natural History in New York. In the last years of his life, he taught biology and evolution at New York University, near his SoHo residence.

Gould's major contribution to science was the theory of punctuated equilibrium which he developed with Niles Eldredge in 1972. The theory proposes that most evolutionary processes are comprised of long periods of stability, interrupted by short episodes and little frequent evolutionary bifurcation. The theory contrasts with phylogenetic gradualism, the widely held idea that evolutionary change is characterized by a continuous, homogeneous pattern.

Most of Gould's empirical research was based on the land snail genera Poecilozonites and Cerion and also contributed to evolutionary developmental biology. In his evolutionary theory he opposed strict selectionism, sociobiology applied to human beings, and evolutionary psychology. He campaigned against creationism and proposed that science and religion be considered two distinct realms, or "magisteria," whose authorities do not overlap ( Non overlapping magisteria in the original).

Many of Gould's essays for Natural History were reprinted in books including Since Darwin and Panda's Thumb. His most popular treatises include books such as The False Measure of Man , The Wonderful Life , and The Greatness of Life . Shortly before his death, Gould published a lengthy treatise recapping his version of modern evolutionary theory called The Structure of Evolutionary Theory (2002).

Biography

Gould was born and raised in the Bayside community, a quiet neighborhood located in Queens, New York. His father Leonard worked as a court reporter, and his mother Eleanor was an artist. When Gould was five years old, his father took him to the dinosaur hall of the American Museum of Natural History, where he first encountered a Tyrannosaurus rex . “I had no idea there were such things; he was amazed," Gould recalled. At that point he decided to become a paleontologist.

Raised in a secular Jewish home, Gould practiced no religion and preferred to be considered an agnostic. Although he "had been raised by a Marxist father", he stated that his father's political views were "very different" from his own. Regarding his political views, he said that they "tend to be center-left". According to Gould, the most influential political books he read were The Power Elite by C. Wright. Mills and the political writings of Noam Chomsky.

While attending Antioch College in the 1960s, Gould was involved in the civil rights movement and frequently campaigned for social justice. At Leeds University, as a visiting student, he organized weekly demonstrations against a Bradford dance hall that refused to admit blacks. Gould continued these protests until that policy was repealed.Throughout his career and in his writings he denounced cultural oppression in all its forms, especially what he saw as pseudoscience used in the service of racism and sexism..

Gould was married twice. His first marriage was to the artist Deborah Lee, in 1965, whom he met when they were both studying at Antioch College, and with whom he had two children, Jesse and Ethan. His second marriage was in 1995 to artist and sculptor Rhonda Roland Shearer, who is the mother of Gould's stepchildren Jade and London Allen.

In July 1982, Gould was diagnosed with peritoneal mesothelioma, a deadly form of cancer that affects the abdominal lining and is often found in people who have been exposed to asbestos. After two years of difficult recovery, Gould published a column for Discover magazine, titled "The median isn't the message", which talks about his reaction to discovering that mesothelioma patients had a median life expectancy of just eight months after diagnosis. He then describes the true meaning behind this number and his relief in realizing that statistical averages are useful abstractions and They do not cover the full range of variation.

The median is the midpoint in statistics which means that 50% of patients die before 8 months, but the other half will possibly live much longer. He needed to determine where his personal characteristics fell within this set of possibilities. Given that his cancer was detected early, and the fact that he was young, optimistic, and had the best treatments available, Gould figured he must be in the favorable half of the upper statistical range. After experimental treatment of radiation, chemotherapy, and surgery, Gould made a full recovery and his spine became an inspiration to many cancer patients.

Gould was also an advocate of medical marijuana. During his fight against cancer, he smoked this drug to relieve nausea associated with his medical treatments. According to Gould, marijuana use had a "very important effect" on his eventual recovery.In 1998 he was a witness in the case of Jim Wakeford, a Canadian medical marijuana user and activist.

His scientific essays for Natural History frequently allude to his non-scientific hobbies and interests. As a child he collected baseball cards and remained an ardent supporter of the sport throughout his life. As an adult he liked science fiction movies, but often lamented their mediocrity (not just in their presentation of science, but in their plots). Other hobbies included singing in the Boston Cecilia Choir, and he was a huge fan. Gilbert and Sullivan operettas. He collected rare and old books. He often traveled to Europe and spoke French, German, Russian and Italian and admired Renaissance architecture. When he spoke of the Judeo-Christian tradition, he referred to it simply as "Moses" and often ruefully alluded to her tendency to gain weight from it.

Gould died on May 20, 2002 of metastatic lung adenocarcinoma, a form of cancer that had spread to his brain. However, it was unrelated to his abdominal cancer, from which he had fully recovered twenty years before. He died at his home, "in a bed set up in the library of his SoHo loft, surrounded by his wife Rhonda, his mother Eleanor, and the many books he loved.".

Scientific career

Gould began his higher education at Antioch College, graduating with a double major in 1963 in geology and philosophy. During this time, he also studied abroad, at the University of Leeds in the UK. Completing his graduate studies at Columbia University in 1967 under Norman Newell, he was immediately hired by Harvard University, where he worked until the end of his life (1967-2002). In 1973, Harvard he was promoted to Professor of Geology and Curator of Invertebrate Paleontology at Harvard's Museum of Comparative Zoology, positions he held until his death in 2002.

In 1982, Harvard University awarded him the honorary title of Alexander Agassiz Professor of Zoology. The following year, in 1983, he was awarded a Graduate Fellowship from the American Association for the Advancement of Science, (« AAAS" where he later served as president (1999-2001). The AAAS press release noted his "numerous contributions to both scientific advancement and public understanding of science". He also served as president of the Society for Paleontology (1985-1986) and vice president at the Society for the Study of Evolution (1990-1991).

In 1989, Gould was inducted into the National Academy of Sciences. From 1996 to 2002 he was the Vincent Astor Visiting Research Professor of Biology at New York University and in 2001, the American Humanist Association named him Humanist of the Year for his work. In 2008, he was posthumously awarded the Darwin-Wallace Medal, along with twelve other scientists. Until 2008, this medal was awarded every fifty years by the Linnean Society of London.

Punctuated Equilibrium Theory

Early in their careers, Gould and Niles Eldredge developed the theory of punctuated equilibrium, which proposes that evolutionary changes occur relatively rapidly, alternating with longer periods of relative stability, as appears to be implied by the paucity of intermediate forms. found in the fossil record. According to Gould, punctuated equilibrium modifies a fundamental pillar "in the central logic of Darwinian theory". Some evolutionary biologists have argued that while punctuated equilibrium was "of great interest to biology", it merely modified the neo-Darwinism in a way that was fully compatible with what was previously known. Others, however, highlighted its theoretical novelty and argued that the evolutionary stalemate had been "unexpected by most evolutionary biologists" and "had a great impact on paleontology and evolutionary biology".

There were also critics who jokingly called the theory "evolution by bumps", leading Gould to describe gradualism as "evolution by drag".

Evolutionary Developmental Biology

Gould made important contributions to evolutionary developmental biology, especially in his work Ontogeny and Phylogeny. In this book he emphasized the process of heterochrony, which comprises two distinctive processes: paedomorphosis and terminal additions. Paedomorphosis is the process where ontogeny slows down and the organism does not reach the end of its development, while terminal addition is the process by which an organism develops by speeding up and shortening early stages of the development process. Gould's influence in this field lives on in areas of research such as feather evolution.

Selectionism and Sociobiology

Gould defended biological constraints, such as developmental pathway limitations on evolutionary outcomes, as well as other nonselective forces of evolution. For example, he viewed many of the higher functions of the human brain as unintended side effects or byproducts of natural selection, rather than direct adaptations. To describe such characteristics he coined, together with Elisabeth Vrba, the term "exaptation". Gould thought that this interpretation undermines an essential premise of human sociobiology (biological determinism) and evolutionary psychology.

Against «sociobiology»

In 1975, E. O. Wilson presented his analysis of human behavior from the point of view of sociobiology. In response, Gould, Richard Lewontin, and other Boston scientists wrote a letter that later had a great impact, to New York Review of Books titled Against "Sociobiology". This open letter criticized Wilson's "deterministic view of human society and action".

Gould, however, did not rule out sociobiological explanations for many aspects of animal behavior; thus he wrote: "Sociobiologists have broadened their range of explanations for selection by invoking the concepts of inclusive fitness and kin selection to solve (successfully, I believe) the vexing problem of altruism—previously the biggest obstacle to a Darwinian theory." of social behavior. [...] Here sociobiology has been and will continue to be successful. And here I wish him well, as he represents an extension of basic Darwinism in a realm where it should be applied."

Enjutas and the Panglossian paradigm

With Richard Lewontin, Gould wrote an influential paper in 1979 entitled St. Mark's spandrels and the Panglossian paradigm, which introduced the architectural term "spandrel" into evolutionary biology. In architecture, a spandrel is a curved area of masonry that exists between the supporting arches of a dome. Spandrels, also called pendentives in this context, are found primarily in Gothic churches.

When visiting Venice in 1978, Gould realized that the spandrels of St. Mark's Basilica, while very beautiful, were not spaces designed by the architect. Rather, the spaces arose as "inevitable architectural by-products of mounting a dome on semicircular arches." That is why Gould and Lewontin defined "spandrels" in the field of evolutionary biology as any biological characteristic of an organism that arises as a secondary and inevitable consequence of other characteristics; that is, it is not directly a product of natural selection. Some examples would include the "masculinized genitalia of female hyenas, the explative use of a navel as an incubation chamber by snails, the hump of the Irish giant deer, and several key features." of the human mentality".

In Voltaire's Candide, Dr. Pangloss is portrayed as a clueless sage who despite the evidence says that "all is better in this, which is the best of all possible worlds." Gould and Lewontin argued that it is Panglossian for evolutionary biologists to view all traits as atomized things that have been naturally selected for, and criticized the biologists for not giving theoretical space to other causes, such as developmental and phylogenetic constraints. The relative ratio of spandrels so defined, versus naturally adapted features, remains a contentious issue in evolutionary biology. An illustrative example of Gould's approach can be found in a study by Elisabeth Lloyd that considers the female orgasm as a byproduct. of sharing pathways of development. Gould also wrote about this topic in his essay Male Nipples and Clitoral Waves, spurred on by Lloyd's earlier work.

Evolutionary progress

The variation proposes, the selection has. - Stephen Jay Gould, Darwinian fundamentalism1997 |

Gould argued that evolution does not have an inherent tendency toward long-term progress. There are often comments that present evolution as a ladder of progress leading to bigger, faster, and smarter organisms, on the assumption that evolution somehow drives organisms to be more complex and ultimately more alike. to the human species. Gould argues that the path of evolution was not towards complexity, but towards diversification. Since life was bound to start from a simple starting point, any diversity resulting from this random walk would be perceived in the direction of greater complexity. But life, Gould argues, can easily accommodate simplification, as is often the case with parasites.

In a review of The Greatness of Life, Richard Dawkins approved of Gould's general argument, but proposed that he had seen evidence of "a tendency for lineages to cumulatively improve their adaptive efficiency." to their particular way of life, increasing the number of characteristics that combine in complex adaptations. [...] According to this definition, evolution by adaptation is not progressive by chance, but is profound, recalcitrant and inevitably progressive».

Cladistics

Gould never embraced cladistics as a method of investigating evolutionary lines and processes, possibly because he was concerned that such investigations would lead him to neglect details of historical biology, which he considered to be of paramount importance. In the early 1990s this led to a discussion with Derek Briggs, who had begun to apply quantitative cladistic techniques to fossils from the Burgess Shale deposit, about the methods to be used in interpreting those fossils.. Around this time cladistics quickly became the predominant method of classification in evolutionary biology. Inexpensive but increasingly powerful personal computers made it possible to process vast amounts of data about organisms and their characteristics. Around the same time the development of effective polymerase chain reaction techniques also made it possible to apply cladistic analysis methods to biochemical traits.

Research with land snails

Most of Gould's empirical research relates to land snails. He focused his early work on the genus Poecilozonites from Bermuda and later on the genus Cerion from the Caribbean. According to Gould “the Cerion is the land snail with the greatest diversity of form in the world. There are 600 described species of this genus. In fact they are not really species, since they all interbreed, but the names exist to express this incredible morphological diversity. Some are shaped like golf balls, others like pencils. [...] Now, my main interest is the evolution of form and the problem of how that diversity can be achieved with so few genetic differences is very interesting. And if we could solve this we would learn something general about the evolution of form."

Given the extensive geographic diversity of Cerion, Gould later lamented that if Christopher Columbus had cataloged a single Cerion it would have ended the scholarly debate over which island was the that Columbus set foot in America for the first time.

The Cambrian Explosion and the Development of the Saltationist Theory

Gould's interpretation of the Cambrian period fossils found in the Burgess shales in his book The Wonderful Life emphasizes the striking morphological disparity (or "rarity") of these faunas; and the role of chance, which determines how many members of it will survive and how many will disappear. The scientist used the life forms of this period as an example of the role that circumstances play in the broad pattern of evolution. After a series of studies based on the comparison between modern trilobites and molluscs, Gould and Eldredge developed the alternative to gradualism, "saltationism", which indicates that species transform rapidly and then remain unchanged for a long time. These studies they allowed Gould to understand that "evolution [...] is adaptation to changing environments, not progress".

This view was criticized by Simon Conway Morris in his 1998 book The Crucible of Creation, whose original English title is The Crucible of Creation. He also promoted the theory of convergent evolution as a mechanism that produces similar forms under similar environmental circumstances, and in a later book argued that the appearance of man-like animals is probable. Paleontologists Derek Briggs and Richard Fortey have also discussed that a significant portion of the Cambrian fauna can be considered as parent groups of extant taxa, although this is still a matter of research and debate, and the relationship between various Cambrian taxa and the The modern phyla has not yet been established in the eyes of many other paleontologists.

Fortey has noted that prior to the publication of The Wonderful Life, Conway Morris shared many of Gould's views, however, after its release, the latter revised his stance and took a more stance. progressive in the context of life history.

The Hierarchical Theory of Evolution

Unlike punctuated equilibrium theory, hierarchical theory is causal in scope, not just phenomenological. The hierarchical theory of evolution generalizes the theory of natural selection to different evolutionary units of the organism: the selection of cell lineages, the classical organismic selection, the selection of groups or demes, of species and even of clades. In this sense, Gould argues that the hierarchical theory does not try to replace, but rather to extend, Darwin's theory. According to the hierarchical theory, evolution is the result of the simultaneous interaction of different levels that can coincide, but also conflict.

For a biological object to be a selection unit, it must have five fundamental properties: birth and death points, sufficient stability throughout its existence, reproduction, and inheritance of parental traits by descent. The first three properties are necessary to distinguish units within a continuum, while the last two are necessary to be considered agents of natural selection, defined as differential reproductive success.

The consideration of an individual as an evolutionary individual is relative, depending on the level of analysis in which we situate ourselves in each case, according to what Gould expressed in The structure of the theory of evolution:

The hierarchical theory of selection recognizes many kinds of evolutionary individuals, ordered in a series of growing inclusion (genes in cells, cells in organisms, organisms in demes, demes in species, species in clades). The focal unit of each level is an individual, and we can direct our attention to any of these levels. Once we designate a focal level as primary for a specific study, then unity at that level (gen, organism, species, etc.) becomes our focal or relevant individual, and its constituent units become parts while the upper level becomes collectivity. Thus, if we focus on the conventional organismic level, genes and cells become collectivities. But if our study requires considering species as individuals, then organisms become parts and nails into collectivities. In other words, the triad part—individual—collectivity will move, as a whole, up and below the hierarchy depending on the subjects and objects of any particular study.

Influence

Gould is one of the most cited scientists in the field of evolutionary theory. His 1979 paper on spandrels has been cited more than 3,000 times. In Palaeobiology, his own flagship journal, only Charles Darwin and G. G. Simpson have been cited more times. Gould was also a highly respected historian of science. Historian Ronald Numbers has stated, "I can't say much about Gould's strengths as a scientist, but I have long considered him the second most influential historian of science (next to Thomas Kuhn)."

As a public figure

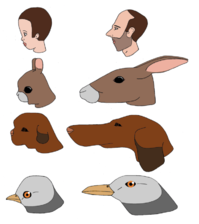

Gould became known through his popular science essays in Natural History magazine and authored several books on evolution. His most popular treatises include books such as The False Measure of Man , The Panda's Thumb , The Wonderful Life and From Darwin . His treatise "A Biological Homage to Mickey Mouse" explains how cartoonists take advantage of the physiognomy of babies, head and large eyes, which give them an appearance that incites tenderness and affection, observations already made by Konrad Lorenz.

He was a passionate advocate of evolutionary theory writing prolifically on the subject and trying to communicate his understanding of contemporary evolutionary biology to a wide audience. A recurring theme in his writings is the history and development of evolution and the thought before the formulation of evolutionary theory. He was also a keen baseball fan; he often made references to the sport in his essays.Many of his baseball essays were collected and published posthumously in Triumph and Tragedy in Mudville (2003).

Although a proud Darwinist, he was less reductionist than most neo-Darwinists. He was strongly opposed to many aspects of sociobiology and its intellectual descendant, evolutionary psychology. He spent much time fighting creationism and related concepts such as creation science and intelligent design theory. Gould later developed the term "non-overlapping magisteria" (non-overlapping magisteria, NOMA, in English) to describe how, in his opinion, science and religion cannot comment on each other's realm. Gould went on to develop this idea in detail in the book Science Versus Religion, a False Conflict (1999) and Once Upon a Time the Hedgehog and the Fox (2003). In a 1982 essay in Natural History Gould wrote:

Our inability to perceive a universal good does not record any lack of perception or ingenuity, but merely shows that nature does not contain structured moral messages in human terms. Morality is a theme for philosophers, theologians, students of humanity and, in fact, for all people who think. The answers cannot be read passively from nature; these, neither arise, nor arise from the data of science. The factual state of the world cannot teach us how, with our powers to [distinguish] good and evil, we must alter or preserve it in the most ethical way.

Gould became a familiar face of science to the general public, often appearing on TV series and shows such as NOVA, Ken's documentary Baseball Burns, Evolution (PBS TV shows), Crossfire (CNN) and others. In 1997 he voiced a version of himself in an episode of the cartoon series The Simpsons .

The "Darwin's Wars"

Gould received praise for his scholarly work and popular exposition of natural history, but was, in turn, heavily criticized by other evolutionary biologists for finding his work alienated from mainstream evolutionary theory. Gould's supporters and detractors have been so bellicose that several commentators have called them "Darwin's wars".

John Maynard Smith, an eminent British evolutionary biologist, was among Gould's harshest critics. Maynard Smith thought that this did not sufficiently take into account the vital role that adaptation plays in biology, and also criticized Gould's acceptance of selection at the species level as an important component of biological evolution. In a review of the book In Daniel Dennet's Darwin's Dangerous Idea, Maynard Smith wrote that Gould "is giving non-biologists a largely false picture of the state of evolutionary theory". Despite these discrepancies, he wrote in a review of Panda's Thumb that "Stephen Gould is the best popular science writer. The Briton was also among those who appreciated Gould's paleontology work. Gould was labeled an "intellectual fraud" by Robert Trivers.

One reason for this criticism was that Gould seemed to present his ideas as a revolutionary way of understanding evolution and argued for the importance of mechanisms other than natural selection, mechanisms that he thought had been ignored by many professional evolutionists.. The result was that many non-specialists sometimes inferred from his early writings that Darwin's explanations had been shown to be unscientific (something Gould never intended to imply). Along with many other researchers in the field, the works of Gould are sometimes deliberately taken out of context by creationists who want to show that scientists no longer understand how organisms evolved. Gould corrected some of these misinterpretations and misrepresentations of his writings in later works.

Gould and Dawkins also disagreed about the importance of genetic selection in evolution. Dawkins argued that evolution is best understood as competition between genes (or replicators), while Gould argued for the importance of various levels of competition, including selection between genes, cell lineages, organisms, groups (demes), species, and clades. Criticism of Gould and his theory of punctuated equilibrium can be found in chapter 9 of Dawkins's The Blind Watchmaker and chapter 10 of Darwin's Dangerous Idea Dennett's. Dawkins later made a concession via an endnote in a new edition of his book The Selfish Gene, where he says:

The progression of evolution can be not so much a steady climb upwards as a series of discrete steps of stable plateau to stable plateau».

This paragraph is a just summary of a way of expressing the well-known theory of punctured balance. I am ashamed to say that when I wrote my conjecture, I, like many biologists from England at that time, was totally ignorant of this theory, although it had been published three years earlier. Since then, as for example in The blind watcher, there was something rash — perhaps too much — about the excessive flattery toward the theory of punctured balance. If this has hurt someone's feelings, I'm sorry. You can point out that at least in 1976, my heart was in the right place.

Opposition to sociobiology and evolutionary psychology

Gould also had a long-standing public feud with E. O. Wilson and other evolutionary biologists over human sociobiology and its later descendant evolutionary psychology (opposed by Gould, Lewontin, and Maynard Smith, but which Richard Dawkins, Daniel Dennett and Steven Pinker advocated. These debates reached their climax in the 1970s, and included strong opposition from institutions such as the Sociobiology Study Group and Science for the People. Pinker accused Gould, Lewontin, and other opponents of the evolutionary psychology from being "radical scientists", whose stance on human nature is influenced by politics rather than science. Gould stated that he "saw no motive behind Wilson or anyone else", but cautioned that all human beings they are influenced, mostly unconsciously, by their personal expectations and biases.

I grew up in a family that participated in social justice campaigns and participated in the civil rights movement as a student in the early 1960s, a time of great emotion and many achievements. Scholars often take care to quote those commitments. [But] it is dangerous for a scholar to imagine that a perfect neutrality can be achieved, because then one ceases to be alert to his personal preferences and influences and then may fall victim to prejudice. Objectivity should be defined operationally as equitable treatment of data, not the absence of preference.

Gould's main criticism was that sociobiological explanations of man lacked evidence, and he argued that adaptive behaviors are often assumed to be genetic for no other reason than their claimed universality or adaptive nature. Gould emphasized that adaptive behaviors can also be transmitted through culture, and both hypotheses are equally plausible. Gould did not deny the importance of biology in human nature, but recast the debate as "biological potentiality versus biological determinism." ». He also claimed that the human brain allows for a wide range of behaviors. Its flexibility "allows us to be aggressive or calm, dominant or submissive, spiteful or generous [...] Violence, sexism, and pervasive meanness are biological, as they represent a subset of a possible range of behaviors. But peace, equality, and goodness are just as biological—and we could see their influence increased if we can create social structures that allow them to thrive."

The false measure of man

Gould is the author of The False Measure of Man (1981), a landmark investigation of psychometrics and intelligence testing. Gould researched the methods of 19th century craniometry, as well as the history of psychological testing. The paleontologist claimed that these two theories were developed on the basis of an unfounded belief in biological determinism, the view that "economic and social differences between human groups (races, social classes, and sexes) [occur by] inherited and innate distinctions and society, in that sense, is an exact replica of biology."

The book was republished in 1996 and added a foreword and review of The Bell Curve. The False Measure of Man has been perhaps Gould's most controversial book. It has received praise, and an extensive series of negative reviews from a wide range of psychologists, including various claims of misinterpretation.

In 2011, a study by six anthropologists criticized Gould's claim that Samuel Morton unconsciously manipulated his skull measurements, arguing that his analysis of Morton was influenced by his opposition to racism. The group's article was briefly reviewed in the journal Nature, which noted that the paper's authors might have been influenced by their own motivations, but concluded that these motivations are not a reason to dismiss their criticism of Gould's claim. group was critically reviewed in Evolution & Developmentt by philosopher of science Michael Weisberg, who argued that although Gould made some mistakes and overstated his case in several places, most of his arguments were sound and that Morton's initial measurements were in fact, tainted by racial bias. In 2015, biologists and philosophers Jonathan Kaplan, Massimo Pigliucci, and Joshua Banta published a paper arguing that no meaningful conclusions could be drawn from Morton's data. They agreed with Gould, and disagreed with the 2011 study, to the extent that Morton's study was seriously flawed; but they agreed with the 2011 study to the extent that Gould's analysis was not in many ways better than Morton's. Anthropologist Paul Wolff Mitchell published an analysis of Morton's original and unpublished data, which neither Gould nor had later commentators directly addressed it, and concluded that while Gould's specific argument about Morton's unconscious bias in measurements does not hold up upon closer examination, it was true, as Gould had asserted, that Morton's racial biases influenced how he reported and interpreted his measurements.

Non-overlapping magisteria

In his 1999 book, Science Versus Religion, A False Conflict, Gould presents what he describes as a "blessingly simple and purely conventional resolution [to the] supposed conflict between science and religion". He defines the term "teaching" as "a domain in which a form of teaching maintains the appropriate tools to craft a meaningful discourse and [arrive at] a solution". The principle of non-overlapping magisteria (Non overlapping magisteria in the original) establishes, therefore, that the magisterium of science covers «the sphere of the empirical: what the Universe is made of (fact) and why it works in a certain way (theory). The teaching of religion extends to questions about ultimate meaning and moral issues. These two magisteria do not overlap, nor do they encompass everything that can be known". He further suggests that "[this principle] enjoys strong and explicit support, even from the most primal cultural stereotypes of the strictest traditionalism" and that "it is a solid position that deserves the general consensus, established after a long fight between people of good will from both magisteriums". However, this position was not without criticism. In his book The God Delusion (The God Delusion), Richard Dawkins believes that this division is not as simple as it seems, since many religions are based on miracles that affect in scientific teaching.

Posts

Articles

During his lifetime, Gould's publications have been numerous. A recap of his publications from 1965 to 2000 lists 479 papers, 22 books, 300 essays, and 101 book reviews written by himself.

Books

The following is a list of books written and/or edited by Gould, including those published posthumously in 2002. Although several of these works were subsequently reprinted by many publishers, this listing maintains the publisher and date of publication. initials and titles in the original language.

- 1977. Ontogeny and Phylogeny. Cambridge MA: Harvard Univ. Press. (Ontogenia and phylogenia. The fundamental biogenetic lawCritics, ISBN 978-84-9892-062-8)

- 1977. Ever since Darwin. New York: W. W. Norton. (From Darwin: Reflections on Natural History, Hermann Blume, ISBN 978-84-7214-278-7)

- 1980. The Panda's Thumb. New York: W. W. Norton. (The thumb of the panda. Reflections on natural history and evolutionCritics, ISBN 978-84-7423-637-8)

- 1981. The Mismeasure of Man. New York: W. W. Norton. (The false measure of manCriticism. ISBN 84-8432-456-7)

- 1983. Hen's Teeth and Horse's Toes. New York: W. W. Norton. (Hen teeth and horse fingersCriticism. ISBN 84-8432-554-7)

- 1985. The Flamingo's Smile. New York: W. W. Norton. (The smile of flamenco. Reflections on Natural HistoryCritics, ISBN 978-84-8432-567-3)

- 1987. Time's Arrow, Time's Cycle. Cambridge MA: Harvard Univ. Press. (The arrow of timeAlliance, ISBN 978-84-206-2736-6)

- 1987. An Urchin in the Storm: Essays about Books and Ideas. N.Y.: W. W. Norton. (A hedgehog in the stormCritics, ISBN 978-84-9199-147-2)

- 1989. Wonderful Life: The Burgess Shale and the Nature of History. New York: W. W. Norton, 347 pp. (Wonderful Life, Burgess Shale and the Nature of HistoryCritics, ISBN 978-84-7423-493-0)

- 1991. Bully for Brontosaurus. New York: W. W. Norton, 540 pp. (Brontosaurus and the minister's buttockCriticism. ISBN 84-8432-619-5)

- 1992. Finders, Keepers: Eight Collectors. New York: W. W. Norton.

- 1993. Eight Little Piggies. New York: W. W. Norton. (Eight pigs. Reflections on Natural HistoryCritics, ISBN 978-84-7423-663-7)

- (ed.) 1993. The Book of Life. New York: W. W. Norton (The Book of LifeCriticism. ISBN 84-7423-626-6).

- 1995. Dinosaur in a Haystack. New York: Harmony Books. (A dinosaur in a haystackCritics, ISBN 978-84-7423-810-5)

- 1996. Full House: The Spread of Excellence From Plato to Darwin. New York: Harmony Books. (The Greatness of Life: the Expansion of Plato's Excellence to DarwinCritics, ISBN 978-84-7423-834-1)

- 1997. Questioning the Millennium: A Rationalist's Guide to a Precisely Arbitrary Countdown. New York: Harmony Books. (MillenniumCritics, ISBN 84-7423-894-3)

- 1998. Leonardo's Mountain of Clams and the Diet of Worms. N.Y.: Harmony Books. (The Almejas Mountain of LeonardoCritics, ISBN 978-84-7423-991-1)

- 1999. Rocks of Ages: Science and Religion in the Fullness of Life. New York: Ballantine Publications. (Science versus religion, a false conflictCritics, ISBN 978-84-8432-052-4)

- 2000. The Lying Stones of Marrakech. New York: Harmony Books. (The Falcon Stones of MarrakechCritics, ISBN 978-84-8432-214-6)

- 2000. Crossing Over: Where Art and Meet Science. New York: Three Rivers Press.

- 2002. The Structure of Evolutionary Theory. Cambridge MA: Harvard Univ. Press. (The Structure of Evolution Theory: The Great Debate of Life Sciences, the Final Work of a Critical Thinker, Tusquets 2004, ISBN 84-8310-950-6)

- 2002. I Have Landed: The End of a Beginning in Natural History. New York: Harmony Books. (I just arrived: the end of a principle in natural historyCriticism. ISBN 84-8432-428-1)

- 2003. Triumph and Tragedy in Mudville: A Lifelong Passion for Baseball. New York: W. W. Norton.

- 2003. The Hedgehog, the Fox, and the Magister's Pox. New York: Harmony Books. (Once upon a time the fox and hedgehog: the humanities and science in the third millenniumCritics, ISBN 978-84-9892-052-9)

Contenido relacionado

Tuberous sclerosis

James I of Aragon

Phlomis herba-venti