Stellar evolution

In astronomy, stellar evolution is the name given to the sequence of changes that a star undergoes throughout its existence.

For a long time, stars were thought to be huge balls of perpetual fire. In the 19th century the first scientific theories about the origin of their energy appeared: Lord Kelvin and Helmholtz proposed that the stars extracted their Gravity energy gradually contracting. But such a mechanism would have allowed the Sun's luminosity to be maintained for only a few tens of millions of years, which did not agree with the age of the Earth measured by geologists, which was already estimated at several billion years. This disagreement led to the search for a source of energy other than gravity; in the 1920s Sir Arthur Eddington proposed nuclear power as an alternative. Today we know that the life of stars is governed by these nuclear processes and that the phases they go through from their formation to their death depend on the rates of the different types of nuclear reactions and on how the star reacts to the changes that occur in it. they are produced by varying their internal temperature and composition. Thus, stellar evolution can be described as a battle between two forces: the gravitational one, which since the formation of a star from a gas cloud tends to compress it and lead it to gravitational collapse, and the nuclear one, which tends to oppose that contraction through thermal pressure resulting from nuclear reactions. Although in the end the winner of this battle is gravity (since at some point the star will have no more nuclear fuel to use), the evolution of the star will depend, fundamentally, on its initial mass and, secondly, on its metallicity and its rotation rate as well as the presence of nearby companion stars.

A star with solar metallicity, low rotation speed and no close companions, goes through the following phases, according to its initial mass:

| Mass Range | Evolutionary phases | Final destination | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower mass: | M | 0.5 MSol | PSP | SP | SubG | GR | EB | ||||||||||||

| Intermediate mass: | 0.5 MSun | M | 9 MSun | PSP | SP | SubG | GR | AR/RH | RAG | NP+EB | |||||||||

| High mass: | 9 MSun | M | 30 MSun | PSP | SP | USGz | USG | SGR | SN+EN | ||||||||||

| Very high mass: | 30 MSun | M | PSP | SP | USG/WR | VLA | WR | SN/BRG+AN | |||||||||||

The names of the phases are:

- PSP: Main presence

- SP: Main sequence

- SubG: Subgigante

- GR: Red Giant

- AR: Red Icetonation

- RH: Horizontal branch

- RAG: Giant asymptotic branch

- SGAz: Blue Supergigante

- SGAm: Yellow Supergigante

- SGR: Red Supergigante

- WR: Wolf-Rayet Star

- VLA: Blue luminous variable

A star can die in the form of:

- EM: Brown dwarf

- NP: Planetary Nebula

- SN: Supernova

- HN: Hipernova

- BRG: Gamma Ray Broth

and leave a stellar remnant:

- EB: White dwarf

- EN: Neutron star

- AN: Black hole

The phases and the limit values of the masses between the different types of possible evolutions depend on the metallicity, the speed of rotation and the presence of companions. Thus, for example, some low or intermediate mass stars with a close companion, or some very massive stars with low metallicity, can end their lives by being completely destroyed without leaving any stellar remnants.

The study of stellar evolution is conditioned by its time scales, almost always much longer than that of a human life. For this reason, it is not possible to analyze the complete life cycle of each star individually, but it is necessary to make observations of many of them, each one at a different point in its evolution, as snapshots of this process. In this regard, the study of stellar clusters is essential, which are essentially collections of stars of similar age and metallicity but with a wide range of masses. Those studies are then compared to theoretical models and numerical simulations of stellar structure.

The main presequence (PSP): From the molecular cloud to the start of hydrogen burning

Stars form from the gravitational collapse and condensation of immense molecular clouds of great density, size, and total mass. The metallicity of the stars that form from the gas cloud will be that of the cloud itself. Normally, the same cloud produces several stars forming open clusters with tens and even hundreds of them. These bits of gas will become accretion or accretion disks from which planets will emerge if the metallicity is high enough.

In any case, the gas continues its fall towards the center of the cloud. This center or core of the protostar is compressed faster than the rest, releasing more gravitational potential energy. Approximately half of that energy is radiated and the other half is invested in heating the protostar. In this way, the nucleus increases its temperature more and more until the hydrogen is ignited, at which time the pressure generated by the nuclear reactions rises rapidly until gravity is balanced.

The mass of the cloud also determines the mass of the star. Not all of the mass of the cloud becomes part of the star. Much of that gas is expelled when the "new sun" begins to shine. The more massive this new star is, the more intense its stellar wind will be, reaching the point of stopping the collapse of the rest of the gas. For this reason, there is a maximum limit on the mass of the stars that can be formed at around 120 or 200 solar masses. Metallicity reduces this limit, something uncertain, because the elements are more opaque to the passage of radiation the heavier. Therefore, a greater opacity causes the gas to stop its collapse more quickly due to the action of radiation.

The continuous struggle between gravity, which tends to contract the young star, and the pressure produced by the heat generated in the thermonuclear reactions inside, is the main factor that determines the evolution of the star from then on.

The main sequence (SP): The longest phase in the life of stars

The main sequence is the phase in which the star burns hydrogen in its core through nuclear fusion. Here the structure of the star essentially consists of a nucleus where the fusion of hydrogen to helium takes place, and an envelope that transmits the energy generated towards the surface. Most stars spend about 90% of their lives on the main sequence of the Hertzsprung-Russell diagram. In this phase, the stars consume their nuclear fuel gradually, being able to remain stable for periods of 2-3 million years, in the case of the most massive and hot stars, to billions of years in the case of medium-sized stars. like the Sun, or up to tens or even hundreds of billions of years for low-mass stars like red dwarfs. Slowly, the amount of hydrogen available in the nucleus decreases, so it has to contract to increase its temperature and be able to stop its gravitational collapse. The higher temperatures of the stellar core allow progressively to fuse new layers of raw hydrogen. For this reason the stars increase their luminosity during the main sequence stage gradually and regularly.

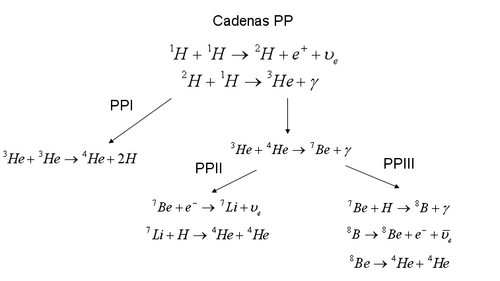

In a main sequence star we can distinguish two ways of burning the hydrogen in the nucleus, the PP chains or proton-proton chains and the CNO cycle or Bethe cycle.

The proton-proton chains are called this way because they are the set of reactions that start from the fusion of a hydrogen ion with another equal, or what is the same, of a proton with another proton. The initials of the CNO cycle refer to the elements that intervene in its reactions, carbon, nitrogen and oxygen. This set of reactions uses carbon-12 as a nuclear catalyst. The CNO cycle is much more sensitive (dependent) to temperature than the PP chains, so at high temperatures (from 2 × 107K) it becomes the dominant reaction and the one that provides the bulk of the star's energy; this occurs in stars more massive than about 1.5 solar masses. Due to this great dependence on temperature, the nuclei of stars in which the proton-proton chain predominates are small and radiative, while those in which the CNO cycle dominates are larger and convective. The shorter limiting time of CNO stars also means that they consume their hydrogen in much less time.

Post Main Sequence Evolution: The Old Age of the Stars

When the hydrogen disappears in the center of the star, the star begins its old age. From this moment on, its evolution will be very different depending on its mass.

Low and intermediate mass stars (M < 9 MSol)

Subgiant (SubG) Phase

When a star less than 9 solar masses exhausts the hydrogen in its core, it begins to burn it in a shell around it. As a result, the star grows larger and its surface cools, so it moves to the right on the Hertzsprung-Russell diagram without changing its luminosity much. This phase is the subgiant phase and is an intermediate stage between the main sequence and the red giant phase.

Red Giant (RG) Phase

As a subgiant evolves to the right (lower temperatures) in the Hertzsprung-Russell diagram, at a given moment the star's atmosphere reaches a critical temperature value that causes the luminosity to increase dramatically while the star it swells to a radius of close to 100 million km: the star has thus become a red giant. It is estimated that within 3-4 billion years the Sun will reach this condition and devour Mercury, Venus and perhaps the Earth.

Like a subgiant, a red giant derives its energy from burning hydrogen into helium in a shell around its inert helium core. The red giant phase ends when said helium also begins to fuse through the triple-alpha process. In stars with masses less than 0.5 solar masses, the core temperature never gets high enough for the triple-alpha process to be activated, so for them this is the last phase in which the star is supported. itself with nuclear reactions.

During the red giant phase, the first dredge-up occurs, in which the nuclear processed material inside the star is transported by convection (typical of the red giant envelope) to the surface, thus becoming detectable.

Phase of the red clump (AR) or of the horizontal branch (RH)

When helium is ignited in stars larger than 0.5 MSun in initial mass, the luminosity of the star decreases slightly and its size decreases. For stars of solar metallicity, the surface temperature does not vary much from the red giant phase and this phase is called red clump because stars of similar masses appear clustered around a point on the Hertzsprung-Russell diagram. For stars of lower metallicity, the surface temperature increases and this phase is called the horizontal branch (in English, horizontal branch), since stars of similar masses appear distributed along a temperature line variable and constant luminosity in said diagram.

The helium burning or fusion process is carried out by a set of reactions that are called triple-alpha because it consists of the transformation of three helium-4 nuclei into one carbon-12 nuclei. By now the core has increased its density and temperature to reach 100 million K (108 K). In the hydrogen fusion stage, beryllium-8 was an unstable element that decomposed into two alpha particles as seen in the PP III chain, and at the temperatures of the second fusion stage it remains so. It happens that, despite its instability, a good percentage of the beryllium produced by the fusion of two helium-4 nuclei ends up joining another alpha particle before it has time to disintegrate. Thus, in the core of the star there is always a certain amount of beryllium in a balance that results from the balance between that which is manufactured and that which disintegrates. The following carbon-to-oxygen conversion reaction then occurs relatively frequently. The problem is that the effective section of said reaction is unknown, so it is not known in what proportions both elements are formed. Regarding the transformation of oxygen-16 into neon-20, this has a small but not negligible contribution. Finally, only a few traces of magnesium will be produced in this second stage.

From the helium it goes to carbon and oxygen so the intermediate elements (Be, B and Li) are not formed in stars. These are manufactured in the interstellar medium by the disintegrations of carbon, nitrogen and oxygen produced by cosmic rays (protons and electrons). Another interesting aspect in helium fusion is the bottleneck that occurs when elements with atomic masses of 5 and 8 cannot be manufactured, since isotopes with said mass number are always highly unstable. Thus, the interactions between helium-4 and other protons or other helium-4 nuclei do not influence the composition of the star but, in the long run, they will increasingly hinder it until it enormously reduces the yield of fusion reactions. of hydrogen.

Phase of the Asymptotic Branch of Giants (RAG)

In time, the helium in the star's core is depleted in the same way that hydrogen was previously depleted at the end of the main sequence. The star then goes on to burn the helium shell and the star re-scales the Hertzsprung-Russell diagram as its surface temperature drops and the star swells again. Because the trajectory followed resembles the one it did earlier in the red giant phase, this phase is known as the asymptotic giant branch. The star will eventually swell to about twice the size it was in the red giant phase.

In this phase the star reaches the greatest luminosity it will ever achieve, since when it ends it will run out of nuclear fuel. The second and third dredging takes place there, in which nuclear reprocessed material surfaces on the surface. Likewise, at the end of this phase the star can manage to reactivate the burning of hydrogen in a relatively external layer of the star. The possibility of burning two different species (hydrogen and helium) in two regions of the star will induce an instability that will give rise to thermal pulses, which will cause a sharp increase in mass loss from the star. Thus, the star will end up expelling its outer layers in the form of a planetary nebula ionized by the core of the star, which will end up becoming a white dwarf.

High Mass Stars (9 MSol < M < 30 MSol)

Stars with a mass greater than 9 MSol have a radically different evolution from those with a lower mass for three reasons:

- Temperatures inside are high enough to burn the elements resulting from the triple-alpha process in successive phases until reaching iron.

- Lightness is so high that the evolution after the main sequence lasts only from one to a few million years.

- Mass stars experience much higher mass loss rates than lower mass. This effect will condition its displacement in the Hertzsprung-Russell diagram.

Thus, stars larger than 9 MSun will go through successive phases of burning hydrogen, helium, carbon, neon, oxygen and silicon. At the end of this process, the star will end up with an internal structure similar to that of an onion, with several layers, each with a different composition.

Blue supergiant (SGAz) and yellow supergiant (SGAm) phases

Having finished burning hydrogen on the main sequence, high-mass stars move rapidly in the Hertzsprung-Russell diagram from left to right, that is, maintaining a constant luminosity but with rapidly decreasing surface temperatures. Thus, the star passes rapidly (in tens of thousands of years or even less) through the blue supergiant (surface temperature around 20,000 K) and yellow supergiant phases. > (surface temperature around 6,000 K) and, in most cases, almost all the helium burning occurs already in the next phase (the red supergiant phase). However, for some masses and metallicities, theoretical models predict that helium burnup will occur when the star's surface is relatively hot. In those cases, the blue and/or yellow supergiant phases may be relatively long-lived (hundreds of thousands to a million years).

Red Supergiant (SGR) Phase

Stars with masses between 9 MSun and 30 MSun and solar metallicity end their lives as Red supergiants. These objects are the largest stars (in size) of the universe, with radios of several astronomical units. Red supergigators have high rates of mass loss, which makes their surroundings large quantities of material expelled by the star.

As already mentioned, a star of this range of masses is capable of burning different elements until it reaches iron. From there, it is no longer possible to extract energy from nuclear reactions and a gravitational collapse supernova is triggered. The stellar remnant will in most cases be a neutron star.

Very high mass stars (M > 30 MSol)

Like stars between 9 MSol and 30 MSol, the stars in this group (the most massive of all), are capable of continuing to burn Nuclearly different elements until reaching iron and producing a supernova. However, there are two fundamental differences with the previous mass range:

- Mass loss rates are so high that the star cannot move to the right end of the Hertzsprung-Russell diagram to form a red supergigante.

- The final remnant will be in most cases a black hole instead of a neutron star.

Very high mass stars are the most difficult to model numerically and the most sensitive to the influence of other parameters such as metallicity or rotation speed. For that reason, the limit of 30 MSol that separates them from those of the previous group is (a) relatively uncertain and (b) highly dependent on these secondary parameters.

Blue Luminous Variable Phase (VLA)

While running out of hydrogen, very high-mass stars shift to the right to become blue supergiants, as do stars with masses between 9 MSol and 30 M< sub>Sun. In doing so, the opacity of their atmospheres increases and they come dangerously close to the Eddington limit. This causes them to enter a highly unstable phase called the luminous blue variable (VLA, in English, luminous blue variable or LBV) during which they shed their outer layers. The most famous VLA is Eta Carinae, which ejected about 10 solar masses of material in a matter ejection that took place in the mid-19th century.

Wolf-Rayet (WR) star phase

As a consequence of the strong mass loss of the most massive stars, especially during the VLA phase, these objects end up shedding their outermost layers to present atmospheres with very low or no hydrogen content. These stars are called Wolf-Rayet stars and are characterized by intense emission lines of elements such as helium, carbon, nitrogen and oxygen. Another peculiar characteristic of these stars is the great difference in mass between their current state and their initial state, as well as the fact that they are less luminous than their progenitor stars. Thus, a Wolf-Rayet star of 8 solar masses could well start its life on the main sequence with 100 MSol. The most massive stars of all get to have such strong stellar winds that they shed their hydrogen outer layers even before they reach the VLA phase.

At the end of the Wolf-Rayet phase, the star exhausts its nuclear fuel and dies producing a gamma-ray burst.

The final fate of the stars: more or less violent deaths

Planetary nebula + white dwarf (M < 5 MSol)

Stars with masses less than 5 solar masses eject their outer layers during the red giant phase and, especially, the giant asymptotic branch phase (those with more than 0.5 solar masses). The resulting stellar remnant is the bare degenerate core of the star, with a composition rich in carbon and oxygen in most cases (although for lower mass stars the dominant element is helium and for higher mass stars there may also be neon). Said remnant is a white dwarf and its surface is initially at very high temperatures, of the order of 100,000 K. The radiation emitted by the star ionizes the recently ejected layers, giving rise to an emission nebula of the type planetary nebula. Thus, isolated low- and intermediate-mass stars end their lives relatively nonviolently.

The planetary nebula is optically observable for tens of thousands of years while the central white dwarf is hot enough to ionize hydrogen from its surroundings. White dwarfs are cooling rapidly, albeit at a slowing rate. A white dwarf lacks additional sources of energy (except during the crystallization period), so its luminosity comes from its own thermal energy. Thus, its temperature will drop to around 2000 K, as the temperature drops, the degeneracy pressure of the electrons is not enough to stop the gravitational collapse and the Bysen-BoH effect produces the so-called class II novae, very energetic explosions that They are believed vital for the formation of living organisms.

Supernova/gamma-ray burst + neutron star/black hole/nothing (M > 9-10 MSol)

Stars larger than 9-10 solar masses (the exact value of the limit is not precisely known and may depend on metallicity) evolve through all fusion phases until they reach "peak iron" to exhaust thus all the nuclear potential energy available to them. The last phases of burning each one passes faster than the previous one until reaching the fusion of silicon into iron, which takes place on a scale of days. The nucleus, unable to generate more energy, cannot support its own weight or that of the mass above it, so it collapses. During the final gravitational contraction, a series of reactions take place that manufacture a multitude of atoms heavier than iron through neutron and proton capture processes. Depending on the mass of that inert nucleus, the remnant that will remain will be a neutron star or a black hole. When the initial remnant is a neutron star, a shock wave will propagate through the outer layers, which will be bounced out. These layers also receive a surplus of energy from the nuclear reactions produced in the last death rattle of the star, much of it in the form of neutrinos. The conjunction of these two effects gives rise to a gravitational collapse supernova.

Depending on the mass and metallicity we have four possible fates for massive and very massive stars:

- For most stars the initial remnant will be a neutron star and a supernova will occur.

- If the initial mass of the star is greater than about 30 solar masses (the exact limit depends on metallicity), part of the outer layers will not be able to escape the gravitational attraction of the neutron star and will fall on it causing a second collapse to form a black hole as a final remnant. This second collapse produces a gamma-ray outbreak.

- In mass stars above 40 MSun and lower metallicity the initial remnant is a black hole, so the outer layers could not in principle bounce against it to produce a supernova. However, current models do not rule out that a weak supernova can be produced, especially if the speed of rotation of the star is high. This group of objects also produces a gamma-ray outbreak.

- For the rare case of very low metallic and mass stars between 140 MSun and 260 MSun There is one last possibility: an explosion of supernova produced by the creation of electron-positron pairs. In that case the star completely disintegrates without leaving a remnant.

The effect on the evolution of metallicity, rotation and the presence of companion stars

Metallicity

The first stars in the Universe were composed almost exclusively of hydrogen and helium. Stellar nucleosynthesis and subsequent expulsion into the interstellar medium has enriched successive generations of stars with metals (elements heavier than helium). Thus, when the Sun was formed, approximately 2% of its mass were metals. Metallicity has the following effects on stars:

- In the main sequence, a poor metal star is smaller in size and its atmosphere is somewhat hotter than that of a star of the same mass richer in metals. This effect is because metals increase the opacity of a star, causing more radiation to be absorbed in its atmosphere, thus increasing its size.

- For most intermediate mass stars metallicity is a crucial factor in deciding whether the burning of helium in nucleus occurs in the phase of the red adhesive or in the horizontal branch.

- For massive stars, metallicity determines the rate of mass loss by star winds: to greater metallicity, more mass lost. This makes the phases going through a star strongly depend on its metal content. For example, the final phase of a solar metallic star and 40 solar masses is the Wolf-Rayet, while a star of the same mass and lower metallicity (with a much lower mass loss rate) the final phase is that of red supergigante.

- As a result of the above, the mass of the remnant of a star will also depend on its metallicity. Thus, it is believed that none of the metallic stars clearly superior to the solar is able to retain enough mass to become a black hole.

The rotation

When a star rotates at high speed, its internal structure can be very different from that of a slowly rotating star. Centrifugal acceleration causes the star to expand in its equatorial region and cease to have spherical symmetry. The equatorial widening is accompanied by a difference in temperature as a function of latitude. For example, Vega (α Lyrae), one of the brightest stars in the sky and a fast rotator (at its equator the speed is 275 km/s), it has a polar temperature of 10,150 K and an equatorial temperature of 7,900 K. The rotation also causes changes in the rate of mass loss, with two distinct effects that favor its increase: at the poles the higher temperature increases the radiation pressure while at the equator the centrifugal acceleration decreases the effective gravity. A high rotation also causes the global luminosity to be greater and greater mixing to occur in the interior of the star, with the consequence that the lifetime increases as the available nuclear fuel increases. All these effects interact in turn with the metallicity of the star, being able to alter the phases that a massive star goes through when leaving the main sequence. So, for example, whether a star with an initial 30 solar masses becomes a Wolf-Rayet or a red supergiant depends on its initial rotation speed.

The presence of companion stars

When leaving the main sequence a star swells. If it has a close companion orbiting around it, the expansion can reach the point of filling the primary star's Roche lobe, so the primary star's atmosphere begins to pour into the secondary. From that point on, the evolution of both stars can be profoundly altered, both in terms of their masses and surface temperatures, as well as the phases they go through and their final destination. There are several possible final destinations of a binary system in which the two partners are within close range. Among the most relevant are type Ia supernovae, X-ray binary systems, and short-duration gamma-ray bursts.

Time scales in the lives of stars

Stars are systems that remain stable for most of their lives. But the changes from one phase to another are transitional stages that are governed on much shorter time scales. Despite this, almost all time scales far exceed the human one. We can distinguish three fundamental time scales:

Dynamic Timeline

This is the time scale that governs when there is a large imbalance between pressure and gravity. This is so in the final moments of a star's life when the nuclear reactions that sustain the star run out of fuel and become unable to stop the collapse. Said time scale is of the order of:

Thus, for the Sun the dynamic time is 1600 seconds, that is, approximately half an hour. As can be seen, if one of the two forces failed, events would happen very quickly until balance was restored.

Thermal time scale

This is the time scale that measures how long the star can survive at a given luminosity from its reserves of gravitational potential energy (Ω). This time scale is also called Kelvin time. This scale, for example, is the one that governs the life of protostars. Its value is of the order of:

For the Sun this gives about 20 million years. For a time this was the only hypothesis to explain the emission of energy from the Sun, and the discrepancy between this short time scale, against geological records dating back billions of years, was a great mystery. This situation continued until the discovery of nuclear energy.

Nuclear Time Scale

The nuclear time scale measures how long the star can survive on its reserves of hydrogen, helium, or whatever fuel it is burning at the time. Its approximate value for the case of hydrogen is:

For the Sun this yields about 9 billion years, which is a rough value for the Sun's stay on the main sequence.

It is therefore clear that: .

Contenido relacionado

Vostok

Arthur (star)

(433) Eros