Statue of Liberty

Liberty Enlightening the World (in English: Liberty Enlightening the World; in French: La Liberté éclairant le monde), better known as the Statue of Liberty, is one of the most famous monuments in New York, the United States and the world. It is located on Liberty Island south of Manhattan Island, next to the mouth of the Hudson River and near Ellis Island. The Statue of Liberty was a gift from the French people to the American people in 1886 to commemorate the centennial of the United States Declaration of Independence and as a sign of friendship between the two nations. It was inaugurated on October 28, 1886 in the presence of the American president of the time, Grover Cleveland. The statue is the work of the French sculptor Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi and the internal structure was designed by the engineer Alexandre Gustave Eiffel. The French architect Eugène Viollet-le-Duc was in charge of choosing the copper used for the construction of the statue. On October 15, 1924, the statue was declared a national monument of the United States, and on October 15, 1965, Ellis Island was added. Since 1984 it has been considered a World Heritage Site by Unesco.

The Statue of Liberty, in addition to being an important monument in New York City, has become a symbol in the United States and represents, on a more general level, freedom and emancipation from oppression. Since its inauguration in 1886, the statue was the first sight European immigrants had when they arrived in the United States after their journey across the Atlantic Ocean. In architectural terms, the statue is reminiscent of the famous Colossus of Rhodes, one of the seven wonders of the ancient world. It was nominated for the new seven wonders of the modern world, where it was a finalist. The name assigned by Unesco is the Statue of Liberty National Monument. Since June 10, 1933, the United States National Park Service has been in charge of its administration.

History

Gift to America

The French jurist and politician, author of Paris en Amérique, Eduardo Laboulaye, had the idea for France to offer a gift to the United States as a gift for the commemoration of the centennial of American independence, as a reminder of the long friendship between the two countries and to guarantee the Franco-American alliance. In a conversation with Laboulaye, his friend, the young Alsatian sculptor Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi, had told him:

je lutterai pour la liberté, j'en appellerai aux peuples libre. Je tâcherai de glorifier la République là-bas, en attendant que je la retrouve un jour chez nousI will fight for freedom, I will ask the free peoples. I will try to glorify the Republic there, until one day between usFrédéric Auguste Bartholdi.

At that time, the United States had just emerged from the civil war that lasted from 1861 to 1865 and the country was in the midst of rebuilding. Bartholdi was hired to design a statue, which was due for completion in 1876, the centennial date of American independence. In 1870, Bartholdi carved the first sketch in terracotta and a model that did not work, which is now in the Museum of Fine Arts in Lyon. That same year, France went to war with Prussia and had to stop the project. On May 10, 1871, France had to cede the territory of Alsace-Lorraine to the German Empire. Public opinion and the French government were disappointed by the sympathy of the United States towards the Germans, who had a significant number of residents on American soil. The project was again partially paralyzed due to the political problems of the Third Republic, which was still considered by many to be a temporary arrangement and which hoped for a return to the monarchy. The idea of offering a representation of liberty in a sister republic to France, on the other side of the Atlantic, played an important role in the fight for the maintenance of the French republic.

In June 1871, Bartholdi traveled to the United States. During the voyage, he chose Bedloe's Island, (later renamed Liberty Island) as the location for the statue and also tried to build a following across the Atlantic. On July 18, 1871, he met with then-President Ulysses S. Grant in New York.

Models for the statue

Inspiration for the figure of the body and face

There are various hypotheses by historians about the model that might have been used to determine the statue's face, though none of them is truly conclusive as of yet. There is definitely an influence from classical Greek art, but on a colossal scale. Recent archaeological discoveries have determined almost exact comparisons between the ancient Greek goddess Hecate and the figure of the statue, as a very accurate inspiration, based on the symbols used, which are, among others, the crown of rays and the torch.

For the face, a model of Isabella Eugenie Boyer, widow of the millionaire inventor Isaac Singer, was used, although according to other sources, Bartholdi would have been inspired by the face of his mother, Charlotte Bartholdi (1801-1891), and it is the most considered hypothesis. to the present. The magazine National Geographic supported this possibility, indicating that the sculptor never explained or denied this resemblance to his mother. Other versions maintain that Bartholdi would have wanted to reproduce the face of a girl perched on a barricade holding a torch, the day after Napoleon III's coup. Perhaps he simply made a synthesis of several female faces, in order to give a neutral and impersonal image of Liberty, inspired by the realistic concept of art ancient hellenic.

Inspiration from abroad

During a visit to Egypt, Bartholdi had to do some work on the Suez Canal. This project began under the direction of the French businessman and diplomat Ferdinand de Lesseps, who later became one of his best friends. Bartholdi imagined a large lighthouse, which would be at the entrance of the canal, which would mark the routes. The lighthouse was conceived as the image with a classical appearance (stole, sandals, facial expression) of the goddess Libertas from Roman mythology, divinity of freedom. The light from the lighthouse was intended to shine through a blindfold placed around the top of the lighthouse, and the idea of a torch held high in the air, toward the sky, arose. Bartholdi presented the project to the khedive Ismail Pasha in 1867 and again in 1869, but the project was never approved. they largely resemble the Statue of Liberty, although Bartholdi asserted that the New York monument was not a reuse, but an original work.

As for the crowning of the head, Bartholdi opted for a sunray diadem, instead of the characteristic Phrygian cap with which the goddess Libertas had always been adorned. The use of this symbol in this type of representation is preceded by two works by the Spanish sculptor Ponciano Ponzano, located in Madrid —in the Congress of Deputies and in the Pantheon of Illustrious Men— and made in 1848 and 1855, respectively.

Structure details

By mutual agreement between France and the United States, the latter would carry out the construction of the base of the monument, while France would be in charge of the construction of the statue and its subsequent assembly once the pieces were transported to the ground US. However, financial problems arose on both sides of the Atlantic.

In France, the campaign for the promotion of the statue began in the autumn of 1875. It was the foundation in 1874 of the so-called Franco-American Union, which took charge of organizing the collection of funds for the construction of the monument. All the means of the time were used for this purpose: articles in the press, shows, banquets, taxes, lotteries, etc. Several French cities, the General Council, the Chamber of Commerce, the Grand Orient of France and thousands of individuals made donations towards the construction of the statue. There was a total number of 100,000 donors. Before the end of 1875, the funds totaled 400,000 francs, but the budget was later increased to 1,000,000 contemporary francs. It was not until 1880. that the total funds were collected in France. Meanwhile, in the United States, theatrical performances, art exhibitions, auctions, as well as professional boxing matches were held to raise funds for the construction.

Meanwhile, in France, Bartholdi sought an engineer to design the internal structure of the statue, in copper. Gustave Eiffel was hired to carry out this work, in addition to creating an internal tower to support the statue and designing a secondary internal skeleton that allowed the copper skin to remain upright. The copper pieces were made in the workshops of the company "Gaget, Gauthier et Cie" in 1878. The copper plates were a donation from Pierre-Eugene Secrétan. The precision work was entrusted to the engineer Maurice Koechlin, a trusted man of Eiffel, with whom he had also worked on the construction of the Eiffel Tower.

Bartholdi hoped the statue would be completed and mounted by July 4, 1876, the centennial date of American independence. There was a delay in the start of construction, and then some problems during the construction period delayed the work: the cast of the hand broke in March 1876. The latter, with part of the arm, was exhibited in September of 1876 at the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition. Visitors were able to climb a ladder that led to the balcony around the torch for as little as 50 cents. Photographs, posters and models of the statue were sold during the exhibition. The money raised was used to complete the works. Two years later, in June 1878, the statue's head was shown to the public in the Champ de Mars gardens on the occasion of the World's Fair in Paris, where visitors could enter the head and climb up to the crown using a 43 meter staircase.

Statue patent

On February 18, 1879, Bartholdi obtained a patent for the monument in the United States, with the number D11.023.

This patent described it in the following terms:

a statue representing Liberty enlightening the world, the same consisting, essentially, of the draped female figure, with one arm upraised, bearing a torch, and while the other holds an inscribed tablet, and having upon the head a diadem,...a statue depicting Freedom that illuminates the world, which consists essentially of a female figure covered, with an uplifted arm holding a torch, and while the other holds a plate inscribed, and has on the head a diadem,...U.S. Patent D11,023

The patent also specified that the statue's face had "classical features, but at the same time it is serious and calm"..., and slightly tilted to the left to rest on the left leg, with the whole figure remaining in balance.

Island Acquisition

The statue is located on Liberty Island in New York Harbor. Originally the island was known as Bedloe's Island, and it served as a military base. Fort Wood was housed in it, an old artillery bastion built in granite and whose foundations in the shape of an eleven-pointed star served as the basis for the construction of the plinth of the statue. Choosing the land and obtaining it required several steps. In 1887, the United States Congress gave its approval for the construction of the statue; and General W. T. Sherman was appointed to designate the land where the monument would be built. He chose Bedloe's Island as the location. Fifteen years before its inauguration, Bartholdi, with great enthusiasm, had already planned the construction of the statue on Bedloe's Island, fascinated by the youth and promises of freedom of that nation, imagining it oriented toward the Europe whose immigrants it had and would continue to welcome. In 1956 the United States Congress changed the name of Bedloe Island to Liberty Island.

The United States Ambassador to France, Levi P. Morton, placed the first rivet on the statue's construction in Paris on October 24, 1881.

Final stage of construction and assembly

Pedestal

The realization of the immense base of the statue had been entrusted by Bartholdi to the Americans, while the French assumed the construction of the statue and its corresponding assembly.

The fundraising to carry out the construction of the base in the United States was under the responsibility of the attorney general, William M. Evarts. Since construction progressed very slowly, Joseph Pulitzer (famous for the prize that bears his name) agreed to make the first pages of New York World available to those responsible for the construction, and carried out a big advertising campaign to raise funds. The newspaper was also used to criticize the upper classes, showing their inability to raise the necessary funds, as well as the middle classes, who counted on the richest to do so. The newspaper's harsh criticism had a positive impact, encouraging the private donors to increase their contributions while also providing publicity to the newspaper, as some 50,000 new subscribers were registered during this period.

The necessary funds for the construction of the basement, designed by the American architect Richard Morris Hunt and carried out by the engineer Charles Pomeroy Stone, were raised in August 1884. The first stone of the pedestal was laid on August 5, 1884, while that the base, mostly made of Kersanton stone, was built between October 9, 1883 and August 22, 1886.

When the last stone of the monument was laid, the masons took several coins from their pockets, and poured them into the mortar. The participants in the ceremony left their business cards, medals, and newspapers in a small bronze chest, and deposited it on the plinth.

At the heart of the block that makes up the base, two series of beams join it directly to the internal structure designed by Gustave Eiffel so that the statue forms a whole with its pedestal. The stone that makes up the base of the Statue of Liberty comes from the quarries of a village in France, Euville in the Meuse department, famous for the whiteness of its stone and for its qualities of resistance to erosion and seawater.

Crossing the Atlantic, assembly and inauguration

The different parts of the statue were finished in France in July 1884. Until then, the statue had received multiple visits, including the President of the French Republic Jules Grévy and the writer Victor Hugo. The disassembly began in January 1885.

The statue was shipped to Rouen by train, then down the Seine by boat, before arriving at the port of Le Havre. The monument arrived in New York on June 17, 1886, aboard the French frigate Isère, and received a triumphant reception by New Yorkers. To make the crossing of the Atlantic possible, the The statue was dismantled into 350 pieces, divided into 214 boxes, taking into account that the right arm and its flame were already present on American soil, where they had been exhibited at the Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition and then in New York. 36 boxes were reserved for the nuts, rivets, and bolts necessary for assembly. Once at its destination, the statue was assembled in four months, on its new pedestal. The different pieces were joined by copper rivets and the dress allowed to solve the expansion problems.

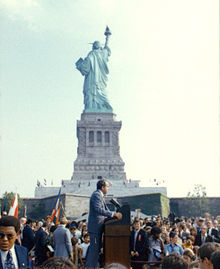

On October 28, 1886, the Statue of Liberty was inaugurated in the presence of the US president at the time, Grover Cleveland, former governor of the state of New York, in front of 600 guests and thousands of spectators. Frédéric Desmons, then vice-president of the French Senate, he represented France at the inauguration. Ferdinand de Lesseps and numerous Freemasons were also present. The monument thus represented a gift celebrating the centennial of American independence, albeit delivered ten years late. The monument's success grew rapidly: in the two weeks following its inauguration, nearly 20,000 people had turned up to admire it. The site's attendance rose from 88,000 visitors a year, to one million in 1964 and three million in 1987. Currently it receives around 3.5 million people a year.

Period as a lighthouse in New York

The statue functioned as a lighthouse between the date of its erection and 1902. At that time, the US Lighthouse Board was in charge of ensuring its operation. A lighthouse keeper had been assigned to the statue and the power of its light beam was such that it was visible from a distance of 39 km. An electrical generator was installed on the island in order to supply power to the structure.

Evolution of the statue

Renovations and reforms

Since its inauguration in 1886, the monument has undergone multiple renovations and alterations:

- Lighting system

The original lighting system has been replaced several times by more modern equipment. In 1916, President Woodrow Wilson inaugurated the first system that met the statue's initial lighting expectations, consisting of two hundred and forty-six projectors, using 250 W incandescent lamps, located at the points of the star at the base of the monument and other points on the island, and fifteen from 500 W in the torch. Later, in 1931 and 1945, the previous lighting was intensified, more showy effects were added and shadows were eliminated.

- Torch redesign

In conjunction with the 1916 lighting improvement project, the torch, originally copper, was refurbished using a total of 600 individual pieces of yellow stained glass to enhance and beautify the lighting effects when lit. This work was executed by Gutzon Borglum, known for his colossal sculptures of Mount Rushmore. The light output of the torch was also increased. On July 30 of that same year, due to an act of sabotage known as the Black Tom explosion, access to the torch was officially closed.

- Elevator and heating

Although when the construction of the base began, the installation of an elevator inside it had already been planned, the first one was not installed until 1908-9. Later it was replaced by a more modern one in 1931.

In 1949 a heating system was installed at the base of the statue. Prior to this improvement, during the winter months, the enormous mass of the base (some 48,000 tons) became increasingly colder, and when the outside air grew warmer in March, condensation formed that permeated the walls and that harmed the structure and its facilities. On the other hand, the heating, in addition to solving the cooling and condensation problems at the base, added greater comfort to employees and visitors.

- Structural improvements

In 1937 several platforms and stairs were replaced on the statue's pedestal. An inspection of the structure and copper plates of the statue was carried out, from the torch to the beams on which the structure rests. The iron support was replaced in sections where it had rusted, and the rivets that had come loose were replaced with new ones and the head-crown frames were rebuilt with new iron ones. No alterations were made to the spiral staircase inside the statue.

Restoration works during the 1980s

The Statue of Liberty was one of the first monuments to benefit from what is known in the United States as a cause marketing campaign. Indeed, in 1983, the monument was the center of a promotional operation carried out by American Express, which was intended to raise funds to maintain and renovate the building. It was agreed that each purchase made with an American Express card would entail a donation of one cent on the dollar by the banking company. The campaign thus allowed to raise 1.7 million dollars. In 1984, the statue was closed in order to carry out work, worth $62 million, carried out on the occasion of its centenary. Chrysler Chairman Lee Iacocca was appointed by President Ronald Reagan to head the commission charged with overseeing the works (although he was later removed to "avoid any doubt about a potential conflict of interest").

Workers in charge of the work erected scaffolding around the building, hiding the monument from view until the centenary ceremony on July 4, 1986. Work inside the structure began with the use of liquid nitrogen in order to remove the different layers of paint applied to the copper frame over several decades. Once these layers of paint were removed, nothing remained but the original tar base that served to cover holes and prevent corrosion. The tar was in turn removed using sodium bicarbonate, without the copper structure suffering any damage. The larger holes in the copper were polished, before being covered by new platelets.

Each of the 1,350 iron ribs supporting the "skin" had to be removed and then replaced. The iron had suffered strong galvanic corrosion in all those parts where it was in contact with the copper skin, losing up to half its thickness. Bartholdi had anticipated this phenomenon and envisioned a combination of asbestos and pitch to separate the two metals, but the insulation had deteriorated decades before. The iron bars were replaced with new bars shaped from stainless steel, with a Teflon film separating them from the copper for better insulation and reduced friction.

The internal structure of the right arm (the one that stands upright holding the torch) has been rebuilt. At the time of the statue's construction, the arm had been displaced 46 centimeters to the right and forward in relation to the central Eiffel structure, while the head had been displaced 0.61 cm to the left, which had been jeopardizing the frame. It is believed that Bartholdi would have made this decision without Eiffel's consent after seeing that the arm and face were too close. Engineers considered the 1937 reinforcement work insufficient, and added diagonal bracing in 1984 and 1986 to make the arm more structurally sound.

The torch that the statue holds in its hand is not the one it held at the time of its inauguration in 1886. During these restoration works it was replaced by a new torch covered with gold leaf, which is illuminated by lamps placed on the balcony that surrounds it. In 1985, to renovate the statue's torch, the United States turned to a company in Bezannes, near Reims, where skilled artisans work in ironwork of works of art. A team from Reims replaced the old torch, corroded by rust, with a new one. The old torch is currently on display in the museum located in the lobby of the monument.

In addition to replacing most of the iron in the internal frame with stainless steel and structural reinforcement of the statue itself, the mid-1980s restoration also included renovation of the internal iron staircase, replacement of the elevator located inside the base by a more modern and improved ventilation control systems.

The Statue of Liberty was reopened to the public on July 5, 1986, during Liberty Weekend.

The centennial celebration of the statue

The Statue of Liberty was unveiled on October 28, 1886, declared a US National Monument on October 15, 1924, and its management entrusted to the National Park Service on June 10, 1933. In 1986, the celebration of the The 100th anniversary of the Statue of Liberty consisted of four days of festivities called Liberty Weekend. The celebrations began on July 3 with an opening ceremony on Governors Island and ended on July 6 at Giants Stadium in New York. These four days of festivities marked the end of the restoration work on the monument carried out since the early 1980s, under the auspices of the Statue of Liberty-Ellis Island Foundation. These works, in which contributions from the Chrysler company played a prominent role, were completed just in time for the monument's centennial ceremony, where tributes were paid to the statue throughout Liberty Weekend.

The inaugural ceremony, held on Thursday, July 3, had the then President of the French Republic, François Mitterrand, as its guest of honor, and attracted numerous celebrities from the entertainment industry, such as Gregory Peck and Elizabeth Taylor. US President Ronald Reagan delivered a speech in which he highlighted the friendship between France and the United States and made mention of the workers who carried out the restoration work. He then rediscovered the statue (covered since the beginning of the works), and delivered a second speech at the moment of lighting the statue's torch, after the display of some fireworks. This was followed by various performances by Neil Diamond, Frank Sinatra and Mikhail Baryshnikov, among others. Finally, the Freedom Medal was awarded to prominent personalities who, although they were not born in the country, acquired US citizenship: Henry Kissinger, Ieoh Ming Pei, Irving Berlin, Hanna Holborn Gray, Kenneth Bancroft Clark, Elie Wiesel, Albert Sabin, James Reston, An Wang, Itzhak Perlman, Franklin Chang-Díaz and Bob Hope.

On the 4th of July, the American national holiday, a naval review of warships and tall ships on the Hudson River, made up of 33 ships from 14 nations. In the evening a concert was held with the participation of the composer John Williams. The next morning, the president's wife, Nancy Reagan, gave a speech marking the official reopening of the statue to the public, and in the afternoon, an opera was held in Central Park. On July 6, the closing ceremony was held at Giants Stadium in New Jersey (which is geographically closest to the statue).

The Aftermath of 9/11

Initially it was possible to visit the interior of the statue. Visitors arrived by ferry to Liberty Island, usually from Battery Park, and had the opportunity to ascend via the unique spiral staircase inside the metal structure. When the statue was exposed to the sun, the temperature inside the monument was often very high. About thirty people could ascend the 354 steps that lead to the head of the statue and its crown. From there it was possible to appreciate views of the New York harbor, although not the urban panorama of Manhattan, contrary to popular belief. This is explained by the fact that the face of the statue is oriented towards the Atlantic Ocean and Europe, not towards the West. Furthermore, the view was partially restricted as the 25 windows in the crown are rather small and the largest of them is only 46 centimeters high. However, this did not discourage tourists, who had to wait three hours on average to access the statue enclosure, not counting the wait at the ferry and the ticket window.

After the attacks of September 11, 2001, access to Liberty Island was prohibited until December of the same year and public access to the monument was not allowed until August 3, 2004. to the crown was closed until 2009. For eight years, only the base of the statue and the first ten floors were open to visitors, provided they were in possession of the monument access pass. It is generally possible to obtain it after making a reservation at least two days before the visit, and to show it before boarding the ferry. However, although the interior of the statue is inaccessible, a new platform with a glass roof allows you to see, looking up, the internal structure made by Gustave Eiffel. All visitors wishing to access Liberty Island are checked before boarding the ferry and again upon accessing the base of the monument, similar to airports.

On August 4, 2006, Fran P. Mainella, director of the National Park Service, in a letter to New York Congressman Anthony D. Weiner, stated that the crown and interior of the statue would remain closed indefinitely. The letter stated that "current access regulations reflect a responsible management strategy in the best interests of all of our visitors". However, there have been multiple initiatives in recent years to reopen the statue to the public and allow access. to the crown. Thus, in the same year 2006, a bill (S. 3597) was processed in the Senate proposing its access to the public, in July 2007 a similar measure was proposed in the House of Representatives, and in July 2008 news emerged about studies by the National Park Service to reform the accesses to the statue to allow public entry. On January 23, 2009, Ken Salazar, Secretary of the Interior under President Barack Obama, declared that he was considering reopening of access to the crown of the Statue to tourists, and on May 8, Salazar announced in an interview on a television program that the crown would reopen to the public on July 4, 2009. Finally, the interior of the statue and access to the crown reopened to the public on the announced day, although for security reasons access was restricted to a maximum of 240 tourists per day in groups of a maximum of 10 people each time.

Access to the public was completely closed again on August 9, 2010 to undertake works to install new fire-proof stairs, elevators and emergency exits, with a budget of 26 million dollars. This intervention, which was already planned, was accelerated after a false fire alarm in July, which revealed the insufficiency of the spiral staircase as the only existing emergency exit. The Statue reopened on October 12, 2011, just days before the 125th anniversary of its inauguration.[update]

Description and symbols

The statue represents a woman in an upright position, dressed in a kind of wide stole and on her head is a crown with seven peaks, symbolizing the seven continents and the seven seas. There are 25 windows in the crown representing gems found on earth and the rays of heaven that shine over the world. The diadem is reminiscent of the one worn by Helios, personification of the Sun in Greek mythology. Bartholdi opted for the crown, and did not decide on the Phrygian cap, a symbol of freedom since Antiquity. The statue brandishes in its right hand a burning torch, held high. The torch takes us back to the Enlightenment, although some consider it a Freemason symbol.In her left hand she holds a tablet, which she holds close to her body. The tablet evokes law or entitlement, and is engraved with the date of the signing of the United States Declaration of Independence, written in Roman numerals: JULY IV MDCCLXXVI.

The structure is covered with a thin layer of copper, which rests on a large stainless steel frame (which was originally made of iron), except for the flame, which is covered with sheets of gold. The structure rests on a square-shaped base, which in turn rests on a first plinth in the shape of an irregular eleven-pointed star. The height of the Statue of Liberty is 46 meters, and it reaches 93 meters from the ground to the torch. At the foot of the structure are broken chains that symbolize freedom. The statue is oriented towards the East, that is to say towards Europe, with which the United States shares its past and values.

The green coloration of the statue is due to chemical reactions, which produced copper salts and gave it its current color. Most outdoor copper statues, unless additional measures are taken, eventually turn this shade after a process called patination.

At the base of the monument, a bronze plaque is engraved with part (the end) of American poet Emma Lazarus's sonnet titled The New Colossus. >). The bronze plaque was not there when it was inaugurated, but was added in 1903. Below is the part of the poem that is inscribed on the plaque, and its Spanish translation:

THE NEW COLOSSUSNot like the brazen giant of Greek fame,

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!"

With conquering limbs astride from land to land;

Here at our sea-washed, sunset gates shall stand

A mighty woman with a torch, whose flame

Is the imprisoned lightning, and her name

Mother of Exiles. From her beacon-hand

Glows world-wide welcome; her mild eyes command

The air-bridged harbor that twin cities frame.

"Keep, ancient lands, your storied pomp!" cries she

With silent lips. "Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tossed to me,THE NEW COLOR

Not like the mythical Greek bronze giant,

From conquerors to tings from land to earth;

Here at our sunset gates bathed by the sea, it will go on.

A mighty woman with a torch whose flame

It's the tight lightning, and his name.

Mother of the Deserts. From the lighthouse of his hand

Welcome to everyone; your tempered eyes dominate

Twin cities that frame the port of air bridges

"Save, old lands, your legendary pomp!" she screams.

"Give me your surrenders, your poor

Your hungry masses longing to breathe freely

The helpless waste of your overflowing beaches

Send me these, the helpless, shaken by the storms to me

I choose my lighthouse behind the golden gate!"Emma Lazarus

The New Colossus (1883)

New York or New Jersey?

Due to Liberty Island's location in the New Jersey portion of the Hudson River, ownership of the statue has not been without controversy.

In 1987 Representative Frank J. Guarini, D-NJ, and Gerald McCann, the former mayor of Jersey City, filed a lawsuit against New York City, asserting that New Jersey should have dominion over Liberty Island given its location on the New Jersey part of the Hudson River. The island, under federal jurisdiction, is approximately 2,000 feet from Jersey City and more than two miles from New York City. The Supreme Court decided not to hear the case, so the existing legal status of the parties of the island that are on the water did not change. However, riparian rights to all submerged land surrounding the statue belong to New Jersey. The islands of New York Harbor have been part of New York City since the issuance in 1664 of the atypical colonial charters creating New Jersey, which did not, as usual, set a mid-Hudson River boundary—although the boundary for water rights was later fixed in the middle of the canal.

The federal park service establishes that the Statue of Liberty is on Liberty Island, that it is federal property managed by the National Park Service, and that the island is officially located within the territorial jurisdiction of the state of New York due to a compact between the state governments of New York and New Jersey which issued a resolution on this issue and which was ratified by Congress in 1834.

Replicas

Due to its consideration as a universal monument, the Statue of Liberty has been copied and reproduced at different scales and in various places throughout the world. These copies range from simple miniatures sold as souvenirs in the museum shop located at the base of the statue, to large-scale reproductions located in certain cities, either because they are part of the history of the monument or of one of its creators, or because the original constitutes an important symbol of Freedom throughout the world.

The first miniatures of the statue, made by the company Gaget, Gauthier & Cie (a fact popularly associated with the birth of the word gadget) were marketed and distributed among the many personalities present during the inauguration ceremony on October 28, 1886. These first reproductions served as models for various replicas built later. Most of them are found today in France or the United States, however we can also see them in many countries, such as Argentina, Austria, Germany, Italy, Japan, China, or even Vietnam, a former French colony.

Among the main French replicas of the monument, we find the one on the Île aux Cygnes (Island of Swans) in Paris, with a height of 11.50 m, which stands at the downstream end of the island (located on the Seine), at the height of the pont de Grenelle, near the former workshop of Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi. There is also a replica in Colmar, inaugurated in 2004 at the northern entrance to the city, commemorating the centenary of Bartholdi's death. Weighing three tons and twelve meters tall, Colmar's Miss Liberty is fifty centimeters taller than her older Parisian sister from the Isle of Swans, until then the largest in France, which also makes her the authentic replica The world's largest Statue of Liberty. There is also a polyester copy of 13.5 m and 3.5 t in weight in Barentin, in the Seine-Maritime, used in the 1965 film Le Cerveau (The Brain), by Gérard Oury. A replica of the statue's torch, the Flamme de la Liberté, gifted by the United States to Paris, is installed on the Parisian place de l'Alma.

In other parts of the world, the most famous replicas of Lady Liberty are those of the New York-New York Hotel & Casino in Las Vegas and the one on the artificial island of Odaiba in Tokyo Bay. In Argentina, there are at least two replicas: one in the Barrancas de Belgrano square in the city of Buenos Aires, made by Bartholdi in red iron and acquired by order of the Municipality of Buenos Aires from France and inaugurated days before his pair of New York, on October 3 of the same year, the second, made after the death of the author, is in the city of Pocito.

In popular culture

The Statue of Liberty quickly became a popular icon, appearing in numerous advertisements and pictures, and in movies and books. In 1911, the American writer O. Henry had Miss Liberty converse with another statue. In 1918, the monument appeared on the advertisement for the Victory Loan) granted by the United States to Europe. In the 1940s and 1950s, numerous science fiction pulp magazines featured the statue surrounded by ruins and remnants from other eras. During the Cold War, the statue often appeared on propaganda posters as a symbol of freedom or of the United States (of course one way or the other, depending on the side in question). American cartoonists showed it as the representation of New York after the attacks of September 11, 2001. Advertising also used it to publicize products such as Coca-Cola or chewing gum. The monument appears on license plates New York State and New Jersey license plates. The statue also inspired 20th century painters such as Andy Warhol.

In the cinema, the statue appears in a large number of films, in some of them with a major role. Already in 1917, in The Immigrant , Charlie Chaplin admires the statue while his ship arrives in the port of New York. In 1942 she appears in Alfred Hitchcock's film Sabotage during the final denouement. At the end of the first version of the film Planet of the Apes, she is shown in a surprising end partly buried under the sand of a beach. In the movie Ghostbusters 2 they manage to make the Statue of Liberty "come alive", walking through the streets of New York. In the most recent filmography, it also makes its appearance in films such as X-Men in which the final battle takes place in the statue, in Titanic where it appears in one of the final scenes of the film when the Carpathia, the ship with the survivors of the sinking, takes them to New York. On the small screen it also appears regularly, as in the television series Fringe, where the statue is the headquarters of the United States Department of Defense in a parallel universe.

In postmodern literature, the novel Banana United States (2011) takes place at the Statue of Liberty in post 9/11 New York City, where Hamlet and Zarathustra meet. directed to free the Puerto Rican political prisoner Segismundo, who is in the dungeons of the Statue of Liberty, imprisoned for more than a hundred years, hidden by his father, the United States King of Banana, for the crime of having born.

In the world of sports, Lady Liberty serves as the logo for the New York Rangers NHL team and the New York Liberty women's basketball team, which competes in the WNBA. To celebrate the centenary of the monument, the French postal service created in 1986 a stamp depicting the face of the statue entitled "Liberty". In the year 2000, the monument was part of the proposals to designate the new wonders of the world, where it was a finalist. The New York University logo retrieves the torch from the Statue of Liberty to show that it is in service to New York City. The torch appears both on the seal and on the logo of the university, designed by Ivan Chermayeff in 1965. The famous illusionist David Copperfield made the monument "disappear" on a live television show in 1983, in one of his most memorable tricks.

The Statue of Liberty in figures

| Height of the statue, from the torch to the base | 46,05 m |

| Total height of the monument, from the ground to the torch | 92.99 m |

| Height from the foot of the statue to the crown | 33,86 m |

| Height of the base, from the ground to the statue | 46,94 m |

| Length of hand | 5,00 m |

| Index | 2.44 m |

| Head, from the chin to the skull | 5,26 m |

| Width of the head | 3,05 m |

| Width of the waist | 10,67 m |

| Width of the eye | 0.76 m |

| Nose length | 1,37 m |

| Length of the right arm | 12,80 m |

| Width of the right arm | 3,66 m |

| Width of the mouth | 0.91 m |

| Height of the tablet | 7,19 m |

| Width of the tablet | 4,14 m |

| Thickness of the tablet | 0,61 m |

| Copper weight | 31 t |

| Steel weight | 125 t |

| Weight of concrete foundations | 25.500 t |

| Thickness of copper plates | 2.38 mm |

Source: Statue Statistics, National Park Service (8/16/2006). Accessed August 18, 2008.

Used bibliography

- Allen, Leslie (1986). Liberty: the statue and the American dream (in English). New York: Summit Books. ISBN 978-06711736.

- Belot, Robert; Bermond, Daniel (2004). Bartholdi (in French). Paris: Perrin. ISBN 978-2-262-01991-4.

- Corcy, Marie-Sophie; Dufaux, Lionel; Vuhong, Nathalie (2004). La statue de la Liberté: le défi de Bartholdi (in French). Paris: Gallimard. ISBN 978-2-07-030583-4.

Additional bibliography

- Gschaedler, André (1992). Vérité sur la Statue de la Liberté et son Créateur (in French). J. Do Bentzinger. ISBN 978-2-906238-26-8.

- Hochain, Serge (2004). Building Liberty: a statue is born (in English). Washington D.C.: National Geographic. ISBN 0-7922-6765-6.

- Lemoine, Bertrand; Institut français d'architecture (1986). La Statue de la liberté (in French). Brussels: Mardaga. ISBN 978-2-87009-260-6.

- Master, Betsy (1989). The story of the Statue of Liberty (in English). Spoken Arts. ISBN 0-688-08746-9.

- Moreno, Barry (2005). The Statue of Liberty encyclopedia (in English). New Line Books. ISBN 1-59764-063-8.

- Nobleman, Mark Tyler (2003). The Statue of Liberty (in English). Mankato: Capstone Press. ISBN 0-7368-4703-0.

- Vidal, Pierre (2000). Frédéric-Auguste Bartholdi, 1834-1904: par la main, par l'esprit (in French). Paris: Créations du pélican. ISBN 978-2-7191-0565-8.

Contenido relacionado

Bartolome de las Casas

Korean war

Gloria Trevi