Spleen

The spleen is an organ present in almost all vertebrates. It is part of the lymphatic system and is the center of activity of the immune system, it facilitates the destruction of red blood cells and old or expired platelets and during the fetal period it participates in the production of new red blood cells (hematopoiesis).

The human spleen is flattened and oval in shape, located in the left upper quadrant of the abdomen, close to the pancreas, diaphragm, and left kidney. It is a highly vascularized organ and its injury causes significant and possibly lethal internal bleeding. Splenectomy allows survival with various complications and rules to be followed.

Human Anatomy

In humans, the spleen is the largest of the lymphatic organs, it is covered by the peritoneum, it is located in the upper left region of the abdomen, behind the stomach and below the diaphragm, attached to it by the phrenosplenic ligament. The spleen is supported by fibrous bands attached to the peritoneum (the membrane that lines the abdominal cavity). It is related posteriorly to the 9th, 10th and 11th left ribs. It rests on the left colic flexure or splenic flexure of the colon, attached to it by the splenomesocolic ligament, and makes contact with the stomach through the gastrosplenic omentum as well as with the left kidney.

Its size is variable, on average it is 13 cm long, 8.5 cm wide and 3.5 cm thick, weighing between 100-250 g. Although it performs very important functions, it is not a vital organ, it can be removed by surgery without compromising life.

Vascularization

Blood that supplies the spleen enters through the splenic artery, a branch of the celiac trunk, entering the organ through an area called the hilum. It immediately branches into 2 branches, one upper and one lower.

These arterial branches divide successively into smaller ones, until they form the central arterioles that form the white pulp. These arterioles branch posteriorly to form perifollicular capillaries. These capillaries ultimately drain into the venous sinuses or sinusoids of the red pulp.

Finally, the venous sinuses of various follicles group together to form the splenic vein that also leaves the organ in the region of the hilum.

Structure

The spleen can be considered in a simplified way as a branching tree of arterial vessels and then arterioles that end in venous sinusoids, where blood filtration takes place, the elimination of microorganisms and the destruction of old red blood cells and platelets.

The structure of the spleen is made up of an external fibrous capsule that gives it its shape and two types of tissue inside the organ: red pulp and white pulp.

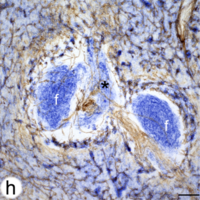

White pulp

The white pulp is part of the immune system, it acts as protection against foreign microorganisms that try to invade the body.

The white pulp consists of lymphoid cells, mainly T lymphocytes and B lymphocytes surrounding a central arteriole.

T and B lymphocytes migrate in special compartments located near the branches of the so-called central arterioles. The white pulp consists of periarterial lymphoid sheaths (PALS) occupied predominantly by T lymphocytes and hemispherical follicles attached to the sheaths where B lymphocytes predominate.

Lymphoid zone

The periarterial lymphoid zone (PALS) contains abundant T lymphocytes.

Lymphoid nodules

In the hemispheric lymphoid nodules or follicles, it is where the B lymphocytes called follicular B cells (Fo B in English) are located. They constitute approximately 20% of the total organ.

Red pulp

The red pulp is basically made up of venous sinuses and cellular cords.

The red pulp contains two types of microvessels, capillaries and sinuses/sinusoids. The blood capillaries form the end of the arterial tree and the sinuses the beginning of the venous part of the splenic circulation. Both types of microvessels in humans are not connected to each other.

The capillaries have open ends that carry blood to cords of reticular connective tissue. Blood plasma and blood cells enter the venous sinuses from the outside through openings in their walls. The spleen shows an open circulation, where blood circulates in spaces that are not lined by endothelial cells, but by fibroblasts.

The red pulp has the function of eliminating waste materials found in the blood, for example defective red blood cells, for this it has special cells called macrophages that engulf these materials.

Function

The spleen performs several functions:

Immune Functions

- Humor and cellular immunity: Seventy years ago a greater predisposition was reported to a serious infection after the removal of the spleen was performed, but it would not be until 1952 when conclusive tests began to be obtained. It is now known that the spleen plays a very important role in immunity, both humoral and cellular. Antigens are filtered from circulating blood and transported to the organ's germ centers, where immunoglobulin M is synthesized. In addition, the spleen is essential for the production of opines, tufsine and properdine, which are important in the phagocytosis of the bacteria with capsule.

Hematic functions

- Hematopoiesis: during pregnancy, the spleen is characterized by being an important producer of erythrocytes (red blood cells) in the fetus. However, in adults this function disappears by reacting only to myeloproliferative disorders that undermine the ability of the bone marrow to produce a sufficient amount.

- Destruction of red blood cells (Splenic hemocateresis): In the spleen there is the elimination of old red blood cells, abnormal or in poor condition. When for different reasons, the spleen is removed, the abnormal erythrocytes that in the presence of the organ would have been destroyed appear in the peripheral blood; being among them, dianocytes and other elements with intracellular inclusions; this function is taken up by the liver and bone marrow. Although the function of the spleen in the human being does not consist of the storage of erythrocytes, it is a key place for the iron deposit and contains within it a considerable part of the available platelets and macrophages to pass to the bloodstream as needed.

In other vertebrates

The only vertebrates that lack a spleen are lampreys and hagfish. Even in these animals, there is a diffuse layer of hematopoietic tissue within the gut wall, which is similar in structure to red pulp and is presumed to be homologous with the spleen of higher vertebrates.

In cartilaginous and ray-finned fish it is composed mainly of red pulp and is usually an elongated organ. In many amphibians, especially frogs, it takes on a more rounded shape and there is often a greater amount of white flesh.

In reptiles, birds, and mammals, the white pulp is always relatively abundant, and in the last two groups, the spleen is typically rounded, although it adjusts its shape somewhat to the arrangement of the surrounding organs. In the vast majority of vertebrates, the spleen continues to produce red blood cells throughout life; however in mammals this function is lost in adults. Many mammals have structures known as blood nodes throughout their bodies that are presumed to have the same function as the spleen. The spleens of aquatic mammals differ in some respects from those of other mammals and take on a bluish color instead of reddish.

Diseases of the spleen

Diseases such as: infections, liver disease and some types of cancer such as lymphomas and leukemias, occur in the spleen.

Blunt splenic trauma occurs from a significant impact on the spleen from an external source, which damages or ruptures the spleen. Treatment varies depending on severity, but often consists of embolism or splenectomy.

Splenomegaly

In medicine, the term splenomegaly is used to describe an abnormal enlargement of the spleen beyond its normal dimensions.

Under normal conditions, the spleen is not palpable in adults. In certain diseases, the spleen enlarges (splenomegaly), which allows its palpation. The medical examination of the spleen is classically divided into two phases, palpation and percussion.

Splenomegaly is not a disease in itself, but rather a symptom that can be due to numerous causes. Some of the most frequent are the following:

- Portal hypertension for some liver disease, for example liver cirrhosis.

- Cancerous processes such as lymphomas and leukemias.

- Infectious diseases such as infectious mononucleosis, malaria and kala-azar.

- Diseases per deposit, including Gaucher and Neimann-Pick disease.

- Abnormalities in red blood cells that cause catching of these blood cells in the red spleen pulp, which causes it to increase in size. This mechanism occurs in thalassemia, sickle cell anemia and autoimmune hemolytic anemia.

Splenic Torsion

The spleen can become twisted for many reasons. One of them is the absence of fixation elements (ligaments), which usually leads to migration of the spleen to different locations within the abdominal cavity, increasing the risk of torsion. Splenic torsion has also been documented in spleens located in their normal position (orthotopic) but without fixation elements.

Splenectomy

Splenectomy is a medical term used to refer to the total or partial surgical removal of the spleen when it is damaged for various reasons. It can be done by two different surgical techniques: open excision or laparoscopic excision. Although the spleen is not a vital organ, i.e. a person who has had it removed can continue to live without apparent problems, it has been observed that individuals who have undergone splenectomy present serious infections by encapsulated bacteria with a frequency between 15 and 20 times higher than the general population. The most frequently implicated infectious agents are: Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, Neisseria meningitidis, Salmonella sp., Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli. These bacteria can cause meningitis, sepsis, and pneumonia.

Contenido relacionado

Erythrocebus patas

Lymph node

Endemism