Spine

The vertebral column, dorsal spine or rachis is a complex, articulated and resistant cartilage and bone structure, shaped like a longitudinal stem, which constitutes the posterior part of the axial skeleton of vertebrate animals and which protects the spinal cord.

In humans and other hominoids, the vertebral column is a set of bones located (at its greatest extension) in the middle and posterior part of the trunk, and runs from the head (which it supports), passing through the neck and back, to the pelvis which it supports.

Column Regions

The vertebral column consists of two main regions in fish: truncal and caudal. In tetrapods, the cervical region related to the neck and the sacral region related to the pelvic girdle are added. In mammals, the trunk region is divided into the thoracic and lumbar. Most mammals have 7 vertebrae in the cervical region.

In hominoid primates, the caudal region is reduced, becoming the coccyx.

Regions of the Spine in Humans

Human beings have 33 vertebrae during childhood and 26 in adulthood (because the vertebrae of the sacrococcal region and the coccyx join together to form one bone each), divided into:

- cervical region (7 vertebrae, C1-C7)

- dorsal or thoracic region (12 vertebrae, T1-T12)

- lumbar region (5 vertebrae, L1-L5)

- sacro-axial region (5 vertebrae, S1-S5)

- coxis (4 vertebrae)

Each region has its own series of characteristics, which are superimposed on those vertebrae close to the other area (such as C7, T12 or L5).

Cervical region

There are seven cervical bones, with eight spinal nerves, they are generally small and delicate. Their spinous processes are short (with the exception of C2 and C7, which have spinous processes that are even palpable). Named from cephalic to caudal from C1 to C7, Atlas (C1) and Axis (C2), they are the vertebrae that allow neck mobility. In most situations, it is the atlanto-occipital joint that allows the head to move up and down, while the atlantoaxial joint allows the neck to move and rotate from left to right. In the axis is the first intervertebral disc of the spinal column. All mammals except manatees and sloths have seven cervical vertebrae, regardless of neck length.

The cervical vertebrae have a transverse foramen through which the vertebral arteries pass, reaching the foramen magnum and ending in the circle of Willis. These foramina are the smallest, while the vertebral foramen is triangular in shape. The spinous processes are short and often bifurcated (except for the C7 process, where a transition phenomenon is clearly seen, resembling a thoracic vertebra more than a prototype cervical vertebra).

In the cervical region, it is possible to distinguish two parts:

-Upper cervical spine (CCA): formed by the occipital condyles, atlas (C1) and superior articular facets of the axis (C2). They make cybernetic movements, adjustment with 3 degrees of movement.

-Lower cervical spine (CCB): from the inferior articular facets of the axis (C2) to the upper plateau of T1. They will perform two types of movements: flexoextension and mixed tilt-rotation movements. This region requires a lot of mobility, it protects the medulla oblongata and the spinal cord. It also stabilizes and supports the head which represents 10% of the body weight.

Both parts of the cervical spine (CCA and CCB) will complement each other to perform pure movements of rotation, inclination or flexion of the head.

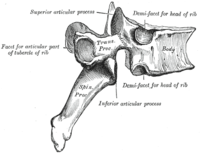

Thoracic region

The twelve thoracic bones and their transverse processes have a surface for articulation with the ribs. Some rotation can occur between the vertebrae in this area, but in general, they have a high rigidity that prevents flexion or excessive excursion, forming the ribs and thoracic cage together, protecting the vital organs that exist at this level (heart, lung and great vessels). The vertebral bodies are heart-shaped with a large anteroposterior diameter. The vertebral foramina are circular in shape.[citation needed]

Lower region

The five vertebrae have a very robust structure, due to the great weight they have to bear from the rest of the proximal vertebrae. They allow a significant degree of flexion and extension, as well as lateral flexion and a small range of rotation. It is the segment with the greatest mobility at the level of the spine. The discs between the vertebrae build the lumbar lordosis (third physiological curve of the spine, with posterior concavity).

Sacral Region

There are five bones that in the mature age of the human being are fused, without an intervertebral disc between each one of them.

Coccyx

In general, the coccyx (also, coccyx) is a group of four vertebrae (in rarer cases, there may be three or five) without intervertebral discs. Many mammalian animals may have a greater number of vertebrae at the level of this region, which are called caudal vertebrae. The pain at the level of this region is called coccygodynia, which can be of diverse origin.

Functions

The functions of the vertebral column are various, mainly it intervenes as a static and dynamic support element, it provides protection to the spinal cord by covering it, and it is one of the factors that help maintain the center of gravity of vertebrates.

The vertebral column is the main support structure of the skeleton that protects the spinal cord and allows the human being to move in a “standing” position, without losing balance. The vertebral column is made up of seven cervical vertebrae, twelve thoracic or dorsal vertebrae, five lower lumbar vertebrae attached to the sacrum, and three to five vertebrae attached to the "tail" or coccyx. Between the vertebrae there are also tissues called intervertebral discs that give them greater flexibility.

The vertebral column also supports the skull.

Constitution

The vertebral column is made up of superimposed and articulated bone pieces, called vertebrae (vertebræ PNA), whose number —erroneously considered almost constant— is approximately 33 pieces, depending on the species.

The vertebrae are shaped in such a way that the spine enjoys flexibility, stability, and shock absorption during the normal locomotion of the organism.[citation needed]

The vertebral column of an adult human measures on average 75 cm in length.[citation needed]

Curvatures of the human spine

Curvatures of the spine are caused not only by the shape of the vertebrae, but also by the shape of the intervertebral discs.

In humans, the spine has several curves, corresponding to its different regions: cervical, thoracic, lumbar, and pelvic.

The cervical curve is convex forward; it is the least marked of all the curves. The thoracic curve is concave forward, and is known as the tt curve. The lumbar curve is more marked in women than in men. It is convex anteriorly, and is known as the lordotic curve. The pelvic curve ends at the coccyx; its concavity is directed forwards and backwards.

The human spine has two main types of curvatures: anteroposterior (ventrodorsal) and laterolateral.

Anteroposterior curvatures

Two types of curvatures are described: kyphosis and lordosis. Kyphosis is the curvature that arranges the vertebral segment with an anterior or ventral concavity and a posterior or dorsal convexity. Lordosis, on the contrary, gives the vertebral segment an anterior or ventral convexity and a posterior or dorsal concavity. The human spine is divided into four regions, each with a characteristic type of curvature:

- Cervical: Lordosis.

- Torácica: ciphosis.

- Lumbar: Lordosis.

- Sacro-coccygea: cyphosis.

In the human newborn, the cervical spine has only one large kyphosis. The lumbar and cervical lordosis appear later.

Side bends

In humans, the vertebral column presents an imperceptible thoracic curvature with convexity contralateral to the functional side of the body. Due to the predominance of the right-handed condition in the population, most present a right convexity lateral thoracic curvature.

Biomechanics

Biomechanically speaking, the spine has two major functions:

First of all, it is a pillar that supports the trunk, and the lower the trunk (lumbar), the more centralized it is with respect to the other components, to better support the load of the hemibody that remains on this area. Likewise, in the cervical region it is also distributed in the center (to support the head), this is what we would see in an anteroposterior cut. This is not the case in the dorsal area due to its function of housing some of the main organs.

Secondly, the spine protects two of the main elements of the central nervous system, which are the spinal cord, housed in its spinal canal and, since it begins in the magnum foramen, also the medulla oblongata.

Of course, we cannot forget the importance of an articulated column that allows the movement of the trunk and the difference that this capacity brings with other species that is bipedalism.

Vertebral functional unit

The vertebral functional unit is made up of two adjacent vertebrae and the intervertebral disc.

In this vertebral unit we can distinguish an anterior pillar, whose main function is support, performing a static function; and a posterior pillar whose function is dynamic.

There is a functional relationship between the anterior and posterior pillars, which is ensured by the vertebral pedicles. The vertebral unit represents a first degree "intersupport" lever, where the facet joint plays the role of fulcrum. This lever system allows damping the forces of axial compression on the disc passively, and active damping in the posterior muscles.

Vertebral Body Overview

The vertebral body has the structure of a short bone; that is, a shell structure with a cortex of dense bone surrounding the spongy tissue. The cortex of the upper face and the lower face of the vertebral body is called the vertebral plateau. This is thicker in its central part where there is a cartilaginous portion. The periphery forms a rim, the marginal labrum. This labrum comes from the epiphyseal ossification point, which is shaped like a ring and joins the rest of the vertebral body around 14 or 15 years of age. Ossification disorders of this epiphyseal nucleus constitute vertebral epiphysitis or Schauermann's disease.[citation needed]

In a vertical frontal section of the vertebral body, one can clearly see, on each side, thick cortices, above and below, the tibial plateau covered by a cartilaginous layer and in the center of the vertebral body spongy bone trabeculae that are distributed following lines of force. These lines are vertical and join the upper and lower plateau, or horizontal that join the two lateral cortices, or also oblique, then joining the lower plateau with the lateral cortices.[citation needed]

In a sagittal section, the aforementioned vertical trabeculae appear again, but, in addition, there are two systems of oblique fibers called fan fibers. On the one hand, a fan that originates in the upper plateau to expand, through the pedicles, towards the superior articular process on each side and the spinous process. On the other hand, a fan that originates in the lower plateau to expand, through the pedicles, towards the two lower articular processes and the spinous process.[citation needed]

The crossing of these three trabecular systems establishes points of great resistance, but also a point of less resistance, and in particular a triangle with an anterior base where there are only vertical trabeculae.[citation required]

This explains the cuneiform fracture of the vertebral body: in fact, before an axial compression force of 600 kg the anterior part of the vertebral body is crushed: it is a crush fracture. To completely crush the vertebral body in addition to making “the posterior wall” yield, an axial compression force of 800 kg is required.[citation needed]

Arch Overview

When a typical vertebra is broken down into its different constituent parts, it can be seen that it is made up of two main parts:

- The vertebral body, ahead.

- The back arch, behind.

The posterior arch has the shape of a horseshoe, on both sides of this posterior arch the mass of the articular processes is fixed, so that two parts are delimited in it.

- On the one hand, the pedicles are located, in front of the mass of the joint apophysis.

- On the other hand, the foils are placed and behind the mass of the joint apophysis.

Posteriorly, in the midline, the spinous processes are attached. The posterior arch, thus constituted, is attached to the posterior face of the vertebral body by means of the pedicles. The complete vertebra also contains the transverse processes, which are attached to the posterior arch approximately at the level of the mass of the articular processes. This typical vertebra is found at all levels of the spine with, of course, major changes either in the vertebral body, in the posterior arch, and generally in both at the same time.[citation needed]

Biomechanics of the bow

Located behind the vertebra is the posterior arch. Supports the articular processes, the stacking of which forms the columns of the articular processes. The posterior pillar plays a dynamic role. The functional relationship between the anterior pillar and the posterior pillar is guaranteed by the vertebral pedicles. If the trabecular structure of the vertebral discs and posterior arches is considered, each vertebra can be compared to a first degree lever, called "intersupport", where the zygapophyseal joint plays the role of fulcrum. This lever system allows the damping of axial compression forces on the spine: indirect and passive damping in the intervertebral disc, indirect and active damping in the muscles of the vertebral sliders, all this through the levers that form each posterior arch. Therefore, the damping of compression forces is both passive and active.[citation needed]

Biomechanics of the Vertebral Body

The vertebral body comprises a laterally concave bone structure, whose dimensions predominate in width, which has a posterior concavity to house the marrow and which is covered with articular cartilage. Its morphology is determined by the great mechanical demands in terms of the transmission of forces to which the entire vertebral spine is subjected, reaching more than 80% of the load.

The upper and lower vertebral bodies adjacent to the intervertebral disc form an amphiarthrosis-type joint. Its main function is to provide stability, supporting mainly compressive stresses. On the contrary, their respective vertebral arches have a dynamic function, providing dynamism to the entire functional structure formed by the three previous elements.

The alteration of the load distribution between the body and the vertebral arch will determine the appearance of facet syndromes, degenerating the posterior interapophyseal massifs due to the increase in the percentage of load supported.

The transmission of loads is modified depending on the curvature of the spine that is subjected to stress:

- In the cervical and lumbar lordosis they occur mainly through the vertebral arches or back pillar.

- In the dorsal and sacral ciphosis through the vertebral bodies or previous pillar.

- In the transition areas, structures subject to major traction forces are the vertebral demands.

Behavior of the vertebral bodies and vertebral arches associated with simple movements of the disc:

- Flexion:

- The upper vertebrae slides forward and decreases the intervertebral space at the previous level.

- The core slides back.

- Autostabilization mechanism (joint action of the pulpy nucleus and the fibrous ring) brakes to prevent further displacement of the upper vertebrae forward.

- The subsequent joint processes are separated.

- Extension:

- The upper vertebrae slides back and decreases the intervertebral space at a later level.

- The core slides forward.

- Self-stabilization mechanism: brakes to prevent further movement of the upper vertebrae backwards.

- The subsequent joint processes are combined.

- Late bending or lateral inclination:

- The upper vertebrae moves to the side.

- The pulpy nucleus slides counterlateral.

- The self-stabilization mechanism: brakes to prevent further movement of the upper vertebra to the side.

- Rotation:

- The upper vertebrae rotates to the side.

- The octopus core rotates in a contralateral sense.

- Increased internal pressure of the pulpy core.

- The self-stabilization mechanism: it brakes to prevent further rotation of the upper vertebrae.

Function of the columns that form the discs and arches

In front is the anterior pillar, whose function is mainly support. Behind are the articular columns, supported by the posterior arch. While the anterior crus performs a static function, the posterior crus performs a dynamic function.

In the vertical sense, the alternating arrangement of the bone parts and the ligamentous junction elements makes it possible to distinguish, according to Schmorl,[citation needed] a passive segment, made up of by the vertebra itself, and a motor segment, which comprises from front to back: the intervertebral disc, the foramen of conjunction, the interapophyseal joints and, finally, the yellow and interspinous ligaments. The mobility of this motor segment, corresponding to the posterior pillar, is responsible for the movements of the vertebral column.

The ligaments attached to the posterior arch ensure the union between two adjacent vertebral arches:

- The yellow ligament, very dense and resistant, which binds to its counterpart in the middle line and is inserted, above in the deep face of the underlying vertebral foil and, below on the upper edge of the underlying vertebral foil.

- The interspine ligament, which extends from behind through the supraspine ligament. This supraspine ligament is not individualized in the lumbar portion; however, it is very sharp in the cervical section.

- The intertransverse ligament, which is inserted at each side at the end of each transverse apophysis.

- Interapofysisary ligaments, which are found in the interapofysis joints and which reinforce the capsule of these joints: previous ligament and posterior ligament.

The set of these ligaments ensures an extremely solid union between the vertebrae, at the same time that it gives the spine great mechanical resistance.

Biomechanics of the vertebral pillars

First of all, it is necessary to know that 80 percent of the body weight falls on the anterior pillar of the spine (static part), and the remaining 20% on the posterior pillar (dynamic part). According to Louis and Bruguer, when these functions are altered, a series of compensations occur (hernias, protrusions...).

Anterior pillar

The anterior pillar of the vertebral column is made up of the vertebral bodies and intervertebral discs. It has a function of support (bodies) and elasticity (discs).

Vertebral body

It is a short bone, with spongy bone tissue inside, which is arranged inside to form bifurcated anastomosed structures called trabeculae, and compact or cortical bone tissue on the surface. The trabeculae are arranged in three directions: vertical, which join the upper and lower faces; horizontal, which unite the lateral cortices, and two systems of oblique lines or fan-shaped fibers. The horizontals are directed from the upper and lower face of the vertebral body, passing through the two pedicles, to the superior, inferior and spinous articular processes. The crossing of the trabecular systems establishes points of strong resistance, as is the case of the pedicles, but also points of less resistance such as the triangle that is formed at the level of the most anterior part of the vertebral body, where there are only vertical trabeculae, for what is the place of settlement of fractures by flexion.

Intervertebral disc

It is a shock-absorbing system that joins two adjacent vertebral bodies forming an amphiarthrosis-type joint. It is made up of a central part called the nucleus pulposus, and a peripheral part called the fibrous ring. The fundamental function is to keep the two vertebrae separated and allow rocking movements between them. 70-90% of the nucleus is water, 65% of its dry weight are proteoglycans (whose function is to retain water) and 15-20% type II collagen (elastic in nature). Collagen content varies depending on its location (it is higher in the cervical discs and lower in the lumbar discs) and age (it decreases with age, therefore its resistance decreases). It has no vessels or nerves, hence its inability to regenerate. As for the fibrous ring, it consists of successive concentric layers of collagen fibers, arranged obliquely with a 30º inclination to the right and left alternately between each layer, which makes them practically perpendicular to each other. This architecture makes it capable of withstanding compressions, but it is poorly prepared for shearing. Its composition is the same as that of the core, but with different relative concentrations (60-70% water and 50-60% collagen) and a different type of collagen, since the ring contains type I collagen, capable of withstanding stresses.

Vertebral Functional Pair

The vertebral functional pair is represented by the union of two vertebrae through the vertebral disc and its connecting elements. It represents an interrest lever of the first type with a fixed point on the veneers.

The joint between two adjacent vertebrae is an amphiarthrosis. It is made up of two plateaus of adjacent vertebrae joined together by the intervertebral disc. The structure of this disc is very characteristic, it consists of two parts: annulus fibrosus and nucleus pulposus.

The annulus fibrosus and the nucleus pulposus together form a functional pair whose effectiveness depends on the integrity of both elements. If the internal pressure of the nucleus pulposus decreases or if the containment capacity of the annulus fibrosus disappears, this functional partner immediately loses its effectiveness.

Annulus fibrosus

This is the peripheral part of the disc made up of a succession of concentric fibrous layers whose obliquity is crossed. The fibers are vertical at the periphery and the closer they get to the center, the more oblique they are.

Nucleus pulposus

This is the middle of the disk. It is a transparent gelatin composed of 88 percent water. There are no vessels or nerves inside the nucleus.

It is enclosed in an inextensible compartment between the vertebral plateaus above, below, and the annulus fibrosus. Therefore, in a first approximation it can be considered that the nucleus pulposus behaves like a marble sandwiched in two planes. This type of joint called "patella" allows three kinds of movement:

- Motion of inclination both in the sagital plane (in this case a bending or extension will be observed) and in the front (side bending).

- Movement of rotation of one of the plateaus in relation to the other.

- Movement of slide or clique of one plateau over another through the sphere.

These movements are of small amplitude. In order to achieve a great amplitude, it can only be obtained by the sum of numerous articulations of this type.

The nucleus pulposus bears 75 percent of the load and the annulus fibrosus 25 percent. The nucleus pulposus acts as a horizontal pressure distributor on the annulus fibrosus.[citation needed]

General movements of the spine

In the normal bipedal posture, the spine and head are in weak balance. Only muscle tone is enough to keep these organs in this position. In a sagittal plane these muscles can be considered to be: dorsally, the musculature of the vertebral canals that extend from the sacrum and iliac to the base of the skull; ventrally, the rectus abdominis major and the scalene muscles. These act on the vertebral bone structure through the thoracic skeleton.

When assessing the mobility of the spine as a whole, it must be taken into account that there are no pure movements (neither flexion, extension, lateral inclinations nor rotations), these are going to be combined in the different segments. The resulting macromovement is due to the sum of the small intervertebral movements. It must also be taken into account that the mobility of the spine will depend on the specific subject.

Bending movement

Flexion:

- Transverse main muscle of the abdomen.

- anterior rectum secondary muscle of the abdomen.

- Spinoese transverse fixer.

Y-axis plane

The movement of flexion of the vertebral column is carried out in a transverse axis within the sagittal or anteroposterior plane of movement (depending on the area, it will be more or less mobilized).

Segmental widths

Segmental amplitudes can be measured from profile radiographs.

- In the lumbar rake: the bending is 60o.

- In the dorsolumbar rake: the bending is 105o.

- In the cervical rake: the bending is 40o.

Therefore, the total flexion of the spine is 110º.

The figures vary from one individual to another and are dependent on gender and age, among other factors.

Overlying vertebra

During flexion, the upper vertebra slides forward and the intervertebral space decreases at the anterior border; the nucleus pulposus moves backwards so that it sits on the posterior fibers of the annulus fibrosus, increasing its tension.

Underlying vertebra

It remains immobile, depending on the vertebral #Functional Unit.

What happens in the vertebral body

Regarding the intervertebral discs, the nucleus suffers a posterior displacement and the posterior fibers of the fibrous ring that surround it (before the separation of the posterior part of the bodies) tighten, preventing the nucleus pulposus from going excessively posterior and get a hernia. This reflex behavior of the annulus fibrosus is part of the self-stabilization system of the disc, and it also occurs in the rest of the movements of the vertebrae, although in different directions.

What happens in the vertebral arch

Due to the posterior separation of the bodies, the vertebral arches also recede and therefore the spinous processes recede from each other so that the interspinous, supraspinous, and flavum ligaments become taut, limiting flexion.

The articular processes are also subjected to tension (as the articular facets tend to separate due to the tilting and ascent movement of the upper vertebra) so that the joint capsule of the zygapophyseal joints is stretched and also limits movement.

As for the transverses, their anterior part tends to come together (the horizontal planes in which they are located become intersecting due to vertebral inclination), while their posterior part tends to separate. As a consequence, the intertransverse ligament is shortened at the front and stretched at the back, also limiting flexion.

Musculature and ligaments

The muscles and extensor ligaments of the back elongate (yellow ligaments, posterior longitudinal ligament, interspinous, supraspinous and intertransverse ligaments, which prevent excess movement of the vertebrae in flexion) and the flexors shorten (anterior longitudinal ligament).

Lateral flexion movement

In the movement of side bending, side bending, or side bending, the spine leans to one side. This movement is carried out in an anterior-posterior axis and in a frontal plane. When sideflexing, the head moves laterally toward the shoulders on the same side and the thorax moves laterally toward the pelvis in the opposite direction.

On the side that is being lateral flexed, the tension decreases, and on the other side, it increases.

The amplitude of the spine with respect to this movement is 20º in the lumbar spine, 20º in the thoracic spine and 35º to 45º in the cervical spine. In the thoracic spine there is less amplitude since the ribs prevent it and in the lumbar spine there is less movement because it is prevented by the articular facets of the lumbar vertebrae.

Due to the lateral separation of the vertebral bodies, the arches are also separated and the articular processes are also subjected to this stress, so the joint capsule of the zygapophyseal joints is stretched and limits movement. The tilting movement of two vertebrae is accompanied by a differentiated sliding of the zygapophyseal joints:

- On the side of convexity, the blades slide as in the bending, that is, upwards.

- On the side of the concavity, the ribs slide as in the extension, that is, down.

Movement limitation is determined by:

- on the one hand, by the bone cap of the joint apophysis on the side of the concavity.

- by the tension of the yellow and intertransverse ligaments on the side of convexity.

In addition, when the spine is flexed laterally, it can be seen that the vertebral bodies rotate on themselves, which causes their anterior midline to be displaced towards the convexity of the curve. On a plain radiograph taken in lateral flexion it can be clearly seen that the vertebral bodies lose their symmetry and the spinous line moves towards the concavity.

In a superior view of the vertebra that is lateroflexed we can verify its rotation, in this position the transverse process of the concavity is projected larger than the transverse process of the convexity. This rotation is physiological, but certain alterations of the vertebral statics caused by a maldistribution of ligamentous tensions or by uneven development determine a permanent rotation of the vertebral bodies. in this case there is a scoliosis that is associated with a permanent lateral inflection of the spine with the pertinent rotations of the vertebral bodies.[citation needed]

Extension movement

This movement is performed in a transverse axis and in a sagittal plane. The total extension of the spine is about 135º and the segmental amplitudes (can only be measured through profile radiographs) are 20º in the lumbar spine, 40º in the thoracic spine and 60º in the cervical spine. It will always be necessary to take into account that these amplitudes vary considerably according to each individual since it is influenced by aspects such as sex or age.

In the extension movement, the overlying (top) vertebra tilts and slides backwards over the underlying (bottom) one, causing the intervertebral space to close posteriorly and open anteriorly.

Thus, the intervertebral disc thins posteriorly and widens anteriorly. Consequently, there is a forward displacement of the nucleus pulposus, which causes an increase in the tension of the anterior fibers of the fibrous ring. This gives rise to the self-stabilizing mechanism causing the anterior fibers of the annulus to pull the overlying vertebra back to its initial position.

The movement will be limited fundamentally by the impingement of the posterior bony elements since the articular processes overlap and the spinous processes are practically in contact. The limitation of extension is also influenced by the tension that occurs in the anterior ligamentous elements. In contrast, the posterior ligamentous elements are stretched and relaxed.

Rotation movement

Y-axis plane

The movement of rotation is carried out in a vertical axis, approximately behind the vertebral arch, at the base of the transverse process. This mechanical arrangement facilitates the probability of this difficult movement. Which, depending on the segment, will have different mobility. We find it a plane of transverse or axial movement.

Segmental widths

Segmental amplitudes can be measured from transverse plane radiographs.

- In the lumbar rake: the rotation is 5o.

- In the dorsolumbar raquis: the rotation is 35o, it is more accentuated than in the lumbar thanks to the arrangement of the joint apophysis.

- In the cervical rake: the rotation is 45-90o. It can be observed as the atlas performs an approximate 90th rotation in relation to the sacral.

Axial rotation between the pelvis and the skull (global) reaches over 90º. In fact, there are a few degrees of axial rotation in the occipitoatlantal bone, but since axial rotation is often less in the thoracolumbar spine, the total rotation barely reaches 90º.

The figures vary from one individual to another and are dependent on sex and age, among other factors.

Overlying and underlying vertebra

During the rotation of one vertebra on another, the sliding of the surfaces in the articular processes is accompanied by a rotation of one vertebral body on another (on their common axis), therefore, by a rotation-torsion of the intervertebral disc, and not from shearing, as is the case with the lumbar spine.

The rotation-torsion of the disc can have a greater amplitude than its shearing: the elementary rotation of two dorsal vertebrae is at least three times greater than that between two lumbar vertebrae.

What happens in the vertebral body and arch

During axial rotation movements, the fibers of the annulus whose obliquity opposes the sense of rotation movement, are tensed. On the contrary, the fibers of the intermediate layers, whose obliquity is reverse, are relaxed. The stress is maximum in the central layers whose fibers are the most oblique: in this case, the core is strongly compressed and its internal stress increases proportionally with the degree of rotation. It is then understood that the movement that associates flexion and axial rotation tends to tear the fibrous ring while, increasing its pressure, expels the nucleus backwards through the fissures of the ring.

Axial rotations are very small movements, from 1 to 2º per functional unit, and it is known that no type of pathology is generated up to 3º, since this increase is perfectly absorbed by the joint and the disc.

Movements are limited by the rotation of the vertebra itself, by the translation of the facets and the middle fibers of the annulus fibrosus, which act like a helical spring. The control of this movement is achieved mainly by the fibrous ring and the morphology of the veneers.

The vertebral facets slide transversely but this has to be accompanied, at the same time, by a translation of the vertebral body of the superior with respect to the inferior.

Musculature and ligaments

In the rotations, it presents a greater control by the joints and the fibrous ring, but despite this, the supra and infraspinatus ligaments act. According to Farfán, if the disc is degenerated, the control by the ligaments increases.

General aspects of the vertebral musculature

Sometimes when we refer to a muscle, we refer to its origin and insertion, its shape and its action, whether static (maintaining the posture) or dynamic (causing movement), on one or more joints, this can help us misleading, and it is thinking that in a movement, gesture or in an action such as maintaining posture, a muscle works individually to produce said movement. Well, this is not normally the case, the muscles usually work by muscular chains.

Anterior or trunk flexor chain

Prevents the trunk or skeleton from falling backwards, that is, when the trunk is extended in favor of gravity, for example falling backwards, the anterior chain controls the movement like a rope, in addition, it causes flexion against gravity and initiates it in favor of gravity, usually combines very tonic muscles with fascias. The navel will be the point of convergence of the flexion forces. It is made up of the following muscles:

- esternocleidomastoideo

- Bathing ladder muscles

- Hioid musculature

- intercostal muscle

- upper rectum or anterior rectum of the abdomen

- pubocoxyge

Upper trunk chain

Prevents the trunk or the skeleton from falling forwards, when the trunk flexes in favor of gravity, the posterior chain controls the movement by putting the posterior muscles in tension. Perform trunk extension against gravity and initiate it in favor of gravity. The spinous process of L3 will be the point of convergence of the extension forces. It is made up of the following muscles:

- neck and head extension muscles

- transversespinous muscles

- supracostal muscle

- average intercostal

- epispine

- dorsal long or Longissimus dorsi

- Iliocostal muscle

- lumbar square (ilio-costal fibers)

- lower posterior serrato muscle and upper posterior serrato muscle

Cross Chains

They produce torsion and rotation movements. These diagonal chains connect the lower and upper limbs. We have an anterior cross chain and a posterior cross chain.

a) Anterior crossed chain: These are muscles connected from the left hemipelvis to the right hemithorax and from the right hemipelvis to the left hemithorax. The muscles that make it up are:

- abdominal oblique muscle

- internal intercostal

- external oblique muscle of the abdomen

- external intercostal muscle

- psoas ilíaco

b) Posterior crossed chain: It is made up of the following muscles:

- external intercostal muscle

- internal intercostal

- lower posterior serrato muscle

- lumbar square (ilio-lumbar fibers)

Abnormalities

Occasionally, the coalescence of the laminae is not complete and consequently a cleft is left in the arches of the vertebrae, through which the meninges (the dura mater and the arachnoid mater) and generally the spinal cord itself protrude, constituting a malformation called spina bifida. The condition is most common at the lumbosacral level, but it can occur in other regions.

The following correspond to abnormal curvatures:

Hyperkyphosis

It is an exaggerated kyphosis at the thoracic level, colloquially known as hunchback, common in older people and secondary to osteoporosis.

Hyperlordosis

Exaggerated lordosis at the lumbar level. Hyperlordosis is common in pregnant women.

Listhesis

It can be anterolisthesis or retrolisthesis, depending on whether the displacement of the vertebral body is forwards or backwards with respect to the adjacent vertebra.[citation needed]

Scoliosis

Lateral curvature, is the most common abnormal curvature, it occurs in 0.5%. It is more common in women and may be the product of uneven growth of the faces of one or more vertebrae. It can cause lung atelectasis and restrictive breathing problems.

Contenido relacionado

Hybrid

Frankeniaceae

Atomic physics